| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

View of Lezha and the Adriatic

from the fortress

(Photo: Robert Elsie, March 2008)

1575

Carlo Ranzo:

Report on a Voyage

from Venice to Constantinople

In this report, Carlo Ranzo describes the overland passage of Venetian Ambassador Giacomo Soranzo through the mountains of Albania to and back from Constantinople. Soranzo was ambassador to London around 1553-1557 and to Constantinople in 1576-1581. This extract recounts the Albanian portion of his harrowing voyage.

Report of Carlo Ranzo, gentleman of Vercelli, on a voyage from Venice to Constantinople, after having returned from the naval Battle of Lepanto. It is very interesting because of all the incidents that are mentioned in it. From it one can learn about military strategies, about the attitudes of the fighters and about the different types of peoples and countries […]

When this gentleman [Ambassador Soranzo] was elected, he put into action all the notable preparations that are required on such occasions. He chose the men from his own court whom he wanted to take with him. There were about forty of them, few of whom were Venetian nobles. Many of them were from other parts of his country. He ordered them to wear long Turkish garments of silk when they were on foot, and short garments when they were on horseback, all in crimson and brownish reds. He bought much silverware, gold brocade, velvet, arras cloth, and crimson and brownish red damask as well as other textiles of similar colours and woven of gold and silk. He ordered several clocks and a quantity of candles and torches of white wax to be taken, as well as many large blocks of Piacenza cheese. He bought these things as presents for the sultan and his pashas, thereby spending a hundred thousand sequins. […]

Having left this town [Dubrovnik], we travelled to Castelnovo [Herceg Novi] that had belonged to the Lords of Venice and was recently captured by the Turks. Passing through a large, eighteen-mile channel, we sailed in to have a look at Cattaro [Kotor], a town belonging to the above-mentioned Lords. It is protected by a very high and very beautiful castle that is splendidly situated and has a good garrison. The town has few citizens because of the plague that raged there recently. [The Ambassador] exacted one hundred thousand sequins from this town. Returning through the said channel, we sailed towards Alessio [Lezha], a town held by the Turks, leaving on our left Dulcigno [Ulqin] and Antivari [Bar], towns that were recently in possession of the said Lords and are now in possession of the Turks.

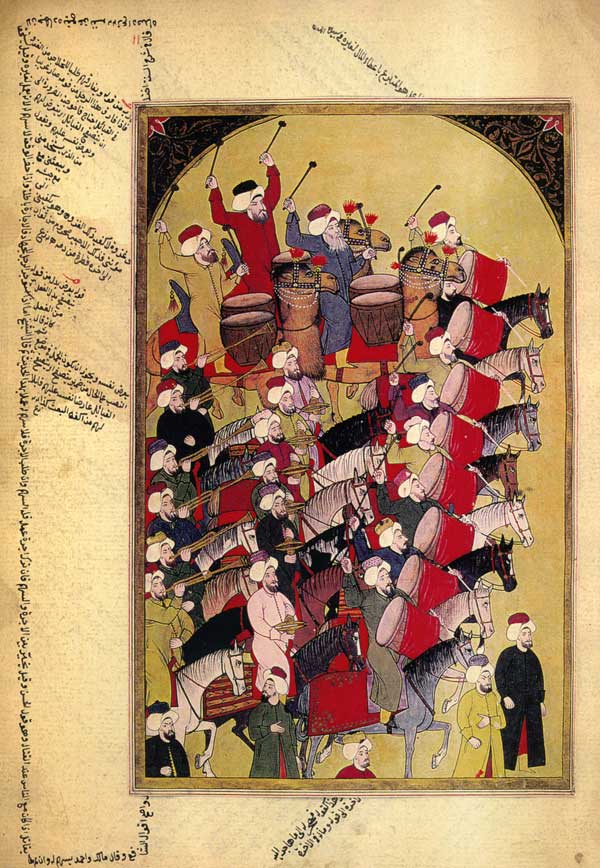

When we got to within three miles of the said town of Lezha, as we could not advance further with our galleys, we anchored there to disembark. An Ottoman adjutant, i.e. an emissary, came out, accompanied by two voivods, some Turkish nobles, four janissaries and some servants. When on the galley, the adjutant kissed His Excellency Soranzo on the hand and informed him that, on orders from his master, he had come out to meet and welcome him and to accompany him to Constantinople so as to ensure his safety along the dangerous roads and to procure horses and other necessities for the journey. He also noted to this effect that he had full authority over all towns and places they might pass through and over the men needed to escort him, and had been asked to serve His Excellency. Having said this, he took leave of us and returned to the town from where he sent us four skiffs covered in carpets and flowers. He also sent porters for the baggage and men to sail the boats and conduct His Excellency into town. Thus, we all disembarked from the galleys to a volley of artillery and arquebuses and to the blowing of trumpets and beating of drums. We got into the skiffs and were taken up a river of fresh water to Lezha, a town destroyed by war. We spent five days in this town waiting for the adjutant to bring us horses because we intended to travel overland from there to Constantinople. In the meantime, the Sandjak Bey of the province presented His Excellency with a fine sorrel horse with a gold-embroidered saddle that had silver studs. He also gave him some castrated sheep and a sack of white bread, as well as many other kind gifts. His Excellency sent the Sandjak Bey a beautiful clock one hand high that marked the hours and quarters of an hour, at a value of one hundred sequins, and embroidered crimson velvet with which to make a long Turkish-style garment, and sent the steward of the place a garment of crimson arras cloth. Many Albanian nobles came to pay homage to His Excellency and brought him many castrated sheep, calves, hares, chickens and ducks, loads of biscuits, white bread, casks of wine of various kinds, and great quantities of salted fish. They showed signs of great affection for the Serene Lords of Venice under whose dominion they had once lived. When the horses were made ready, we set off from this town, accompanied by the said adjutant, the voivods and the four janissaries. We rode over a fair plain that stretches for 22 miles and arrived at the foot of the mountains through which we were to travel for several days. As it was late, we raised our tents to spend the night there. In the meantime, the adjutant sent the voivod to the nearest settlement to bring back a number of men who would guard us on our way. Thus, at midnight, we were presented with two hundred Albanians, inhabitants of a mountainous region called the Upper Black Mountains [Karadaku i Shkupit / Skopska Crnagora], where because of the height of the mountains, they never see the sun. In the mountains, we could hear the drum that was being beaten to inform the inhabitants that a large group of men was passing through. The man beating the drum looked like a bird to us. These people are dark-skinned. Their heads and beards were shaven, except for their moustaches. Their shirts were black with filth and they were very poorly dressed. They looked like men from hell – savage and frightening in appearance. They carried wooden bows and arrows next to their rusty swords, with wooden sheathes. On their heads, they wore caps like red berets, all greasy and ugly, and when they clambered down their mountains, they gave out cries that seemed not to be human but rather like the raging of a bull. The women, dark-skinned, too, were strong and healthy-looking, more so than the men. They wore three chains of aspers as necklaces and bracelets. These aspers, silver coins, are worth sixty to a sequin. These women brought food to our tents. There were so many women that it looked like market day. They were Christians. Accompanied by these Albanians, we rode for fourteen days through the mountains called the Black Mountains of Skopje. When we got to the highest and last mountain, we could see the Black Mountains of Armenia where it is said that Noah’s Ark was. But they were difficult to distinguish because there were a lot of trees. Not even a bird could be seen. During the journey we did not stay in any of the villages or other places, but always spent the night in our tents. So, too, did the adjutant with the voivods and janissaries, while the said Albanians kept guard on the mountain passes and around our tents. Nonetheless, we were full of suspicion and fear because there were many killings in those mountains, on the roads and in the forests. We were afraid because we did not feel secure and had no confidence in those men who had come to guard us and accompany us, because they were of an evil, barbaric nature and respected and submitted to no one. Indeed they lived unbridled like the wild beasts. They ate only dough baked in coals and ashes, nothing else. When we got through the mountains, we arrived at a town called Scoppia [Skopje] which is inhabited primarily by Jews from Ragusa [Dubrovnik], Turks and other merchants who conduct much trade and have made the town very popular. We stayed for three days in that town, where we were put up very comfortably at the home of a very wealthy Dubrovnik merchant. His Excellency presented the governor of that province with calves, castrated sheep and sacks of bread. The many Jews brought him sweets, marzipan, candies, castrated sheep and yellow candles. His Excellency gave the governor a little clock worth 50 scudi and gave his steward, called Diacali, a scarlet garment. Here, the adjutant had the horses changed and, having released the Albanians, he ordered others to come and guard us. We set off with them and continued for three days, once again through the mountains, but the terrain was not as difficult as it had been. We crossed a river on boats, but the boats were so small that no more than three or four men could cross at one time. I was first to cross with two companions. Then His Excellency Soranzo crossed. He ordered us to remain there until all the baggage had been brought over. This took until evening […]

In the meantime, Gabriello Zerbellone and Don Giovanni da Mariano and the knight Birago and Tomaso Costanza, a Cypriot, arrived to pay their respects to His Excellency and have a meal with the said ambassador. They had been taken prisoner in the fighting when Goletta was captured as they happened to be in that city with others who were taken prisoner in Famagusta and were jailed in a tower on the Black Sea. Let out, i.e. freed of their chains, they were being escorted by the Turks, who were taking them to Dubrovnik to be released in exchange for some Turkish prisoners who had been held in Rome and were being sent to Dubrovnik […]

When the order was given [for the return journey], we left the city [Constantinople] after His Excellency had hosted a magnificent dinner for the Ambassador of France and the two representatives of Venice. One of them, the Most Illustrious Tiepolo, was to leave Constantinople two or three days after our departure, whereas the other one, the Most Illustrious Giovanni Correr, remained at his post. His Excellency Soranzo was accompanied to the border of the State of the Grand Turk by two janissaries on horseback. These janissaries had authority to order all subjects of the Sultan to provide all requisite assistance and support for our personal safety and for our belongings, as well as for food and lodging along the way. This trip was very different from the outward journey because, not only were we now faced by bad winter weather, but we also took a different route. This time we travelled along a very bad road through a mostly mountainous wilderness with few inhabitants. For this reason, we often had to seek shelter in stables built of wood. There were no towns on the way and we could not use our tents because of the inclement weather. There was much snow and a very icy wind and, after spending many days on the road, we arrived at a city called Salonika, a large and populated town by the sea, inhabited more by Jews than by Muslims. We stayed there for three days. In this town, there is a building made entirely of porphyry, with columns and vases made of the same. It is estimated to be worth 400,000 sequins as it is all covered in porphyry. Many of the Jews of this town came to meet His Excellency and gave him gifts, including baskets of bread, barrels of wine, many biscuits, sweets and wax candles. Having departed, we rode over the mountains with the janissaries to Bastia, a place not far from Corfu, which is the border of the State of the Grand Turk. Here, His Excellency Soranzo was planning to sail over to Corfu without entering Bastia, that is situated on a high mountain over four miles from the sea, but since the galleys that were coming through the Channel of Corfu to pick him up had not yet arrived and since there was heavy rain and we had no other place of shelter, a decision was taken that we go up to Bastia and stay there until the galleys arrived. Riding up the mountain, Soranzo encountered the local Cadi, that is, the judge, and the Emin, an important figure who was responsible not only for customs and other revenues of the Sultan, but looked after other affairs of state and had authority over the army in that border region, in particular over the guards. Indeed, not only did they come out to meet His Excellency and accompany him to the town, but they also brought with them gifts such as kid meat and other foods, and spoke most hospitably. As such, His Excellency Soranzo, who had brought with him about thirty expensive horses purchased in Constantinople, having been received with such great courtesy, was promised that they would allow him to take the thirty horses abroad with him, even though His Excellency had not had this included in the orders issued by Mehmet Pasha concerning the people and goods he might take with him anywhere. The orders mentioned only two horses, a dapple and a sorrel one, that had been given to him by the sultan and the said pasha. There would have been a heavy penalty for taking the horses out of the country without permission and a special order from Mehmet. His Excellency had faith in the courtesy and good intentions these people had shown him. However, the janissaries, who had accompanied him from Constantinople, having learned of this, secretly intervened and expressed their opposition to the Cadi and Emin and stated that if the latter were to allow the horses to pass without permission or some other order, they would have them charged before the sultan as soon as they returned to Constantinople. Thus, terrified by the words and ill-intent of the janissaries, they began to excuse themselves in front of His Excellency for not being able to satisfy him in this matter, because the janissaries would otherwise carry out their threats. As such, things did not turn out as had been hoped. In the meantime, when the galleys arrived, His Excellency requested permission to use the horses to ride down to the place where he would embark, and since the horses could go no further, he would leave them there so that they could be bought by someone who needed them. They accepted this proposal and granted his request. When we got to the galleys, they noticed a large number of soldiers from the Corfu garrison disembarking, who were preparing to welcome His Excellency Soranzo with a volley of fire. Fearing that they had come to assist us in loading the said horses and taking them with us without their permission, they gave immediate orders to the Albanian rabble, armed with iron rods, to pursue us and force us to leave the horses there, not even allowing us to reach the galleys. Thus, some of the peasants, as if they had been lying in wait and preparing for this action, rushed up behind us and began beating us savagely. Others arrived on the spot and acted with even greater fury, as did some spahees or light cavalrymen, who serve in border regions, so that we were overwhelmed and forced to submit to the fury of the rabble and hand over the horses to them, among which was the horse that the Sandjak Bey of Lezha had given to His Excellency. With every man trying to save himself in the scuffle, we scrambled onto skiffs to get to the galleys and were not able to take more than three horses. When His Excellency arrived in Corfu, he wrote to Mehmet Pasha about the barbaric treatment and insult he had been subjected to, noting that they had forcefully and illegally taken away not only the horses he had bought in Constantinople for the journey, that he had promised to leave in the country, but also another horse he was particularly fond of, given to him by the Sandjak Bey of Lezha […]Later, soon after we arrived in Zara [Zadar], the horse was returned to him in good condition, on orders from the said pasha, and all the other horses that had remained behind in Bastia were paid for […]

[Extract from Carlo Ranzo, Relazione d’un viaggio fatto da Venezia a Constantinopoli, 1616; published in: Giovanni Sforza, Viaggio attraverso i Balcani nel 1575 (Siena: Stab. Lazzeri, 1915), p. 21-52; Marziano Guglielminetti, Viaggiatori del Seicento (Turin: UTET Libreria 2007); and in Injac Zamputi, Dokumente të shekujve XVI-XVII për historinë e Shqipërisë, Vëllimi 1, 1507-1592 (Tirana: Akademia e Shkencave, 1989), p. 327-340. Translated from the Italian by Robert Elsie.]