| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

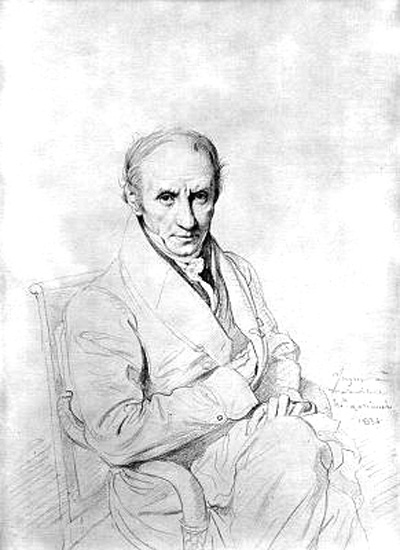

François Pouqueville by Ingres, 1834

1806

François Pouqueville:

Travels in Epirus and Albania

French historian and diplomat François Charles Hugues Laurent Pouqueville (1770-1838), born in Le Merlerault (Orne) in Normandy, was educated in Caen and Lisieux and studied medicine at the Sorbonne in Paris under Antoine Dubois. As a physician, he took part in the French expedition to Egypt. On 25 November 1798, on his way back to France, he was captured by pirates and sent to Navarino in the Peloponnese, where he was imprisoned and held for ransom by the Turks. He spent two years in prison in Istanbul and returned to France in 1801. It was in prison that he began writing his first travel memoirs, which were dedicated to Napoleon and published in the three-volume edition: “Voyage en Morée, à Constantinople, en Albanie et dans plusieurs autres parties de l’Empire othoman pendant les années 1798, 1799, 1800 et 1801,” Paris 1805 (Travels in the Morea, to Constantinople, Albania and several other parts of the Ottoman Empire in the years 1798, 1799, 1800 and 1801). The book, translated into German, English and Italian, was exceptionally successful and attracted the attention of the French government, which appointed him as consul general in Janina, to the court of Ali Pasha Tepelena. He remained in Epirus from 1806 to 1815, had a close personal relationship with the “Lion of Janina” and was able to travel widely in the region. The following extract from the English translation of his “Travels in Epirus, Albania, Macedonia, and Thessaly,” London 1820, offers a detailed description of his impressions of Epirus and southern Albania in early 1806. The modern placenames have been added here in square bracket.

Voyage along the Coast of Albania and Epirus,

from Ragusa to Port PalermoImmediately after our arrival in Ragusa we dispatched a Tartar by land, to acquaint Aly, Pasha of Janina, with our position, and to solicit his instructions and assistance in repairing to his court. By Tartars, or more correctly Tatars, are meant messengers, couriers, or guides on horseback, employed over the Turkish dominions. The first persons so employed having been in fact Tartars, the name is still applied to their successors, of whatever country they may be. Thus in France the porters at the gates of palaces, public offices, hotels, &c. are still styled Swiss, because in former times natives of Switzerland were usually selected for porters, on account of their characteristic fidelity and attachment to their masters. With great difficulty and delay, on account of the snow and other obstacles, our Tartar accomplished his mission; and Aly, foreseeing that we strangers should encounter many more impediments and dangers in traversing the country, dispatched a vessel to carry us to one of his own ports. But the vessel was wrecked on the coast, and the crew had to hire barks to convey them to Ragusa, where our long residence seemed at last to create some uneasiness in the ruling powers. We learned also that the Turkish governors would most probably oppose our journey through their territories, on our way to their hated neighbour Aly of Janina. While in this embarrassing situation a French privateer put into Santa Croce, or Gravosa, an excellent haven on the north side of Ragusa. Embarking in that vessel on the 22d of January, 1806, we sailed in company with another French privateer for Port Palermo, the nearest port belonging to Aly, seven leagues to the northward of the island of Corfu. In the evening we observed the sun to set between the summits of Mount St. Angelo, formerly Mons Garganus, in Apulia in Italy, distant west-south-west forty leagues. Our course lay first south-east until we came off Durazzo, the ancient Dyrrachium and Epidamnus, a port and fortress memorable in various periods of history, particularly for the operations in its vicinity between Cæsar and Pompey, previous to the decisive action of Pharsalus. There the Albanian coast runs southward to the entrance of the bay of Valona [Vlora], where the Sirocco, or south-east wind setting in strong, we came to anchor under the protection of Saseno [Sazan], an island lying before it. The wind threatening to continue for some time, as it generally does in winter in the mouth of the Adriatic, we passengers landed in a small sandy bay on the north-east part of the island, the only spot where it is accessible. Knowing it to be uninhabited we carried on shore an old sail, with which we constructed a sort of tent. We had also on shore our Tartar and a Wallachian of Epirus, whom Aly had sent along with him, to serve as our guide and interpreter when we should land in his territories. We soon, however, discovered that we were not alone in Saseno. Smoke rose up in several places, and in a little time appeared a number of Albanians in arms, observing us with keen attention. The strangers were shepherds from the adjoining coast, who are in the habit of transporting to the island large numbers of sheep and cattle in winter. Intercourse being opened with them through our interpreter, we procured some sheep for ourselves and for the people on-board the privateer; and a fire being kindled the Albanians with admirable dispatch fitted one of the sheep for the spit. In the night the south-east gale grew tempestuous with heavy rain and long and vivid lightning; well reminding us of the Ceraunian or thunder-stricken mountains in our near vicinity. It was with the greatest difficulty that our vessel kept her place.

The island Saseno, the Sazon, Sason, or Saso of the ancients, is situated in the entrance of the bay of Aulon, or Valona, distant from the north point twice as far as from the south point Cape Linguetta, or Glossa, the famous Acroceraunium of antiquity, situated in 40 deg. 26 min. 15 sec. north latitude. The island is about a league in length from north to south, and the distance across the Adriatic from it to the nearest part of Italy (the narrowest part of the entrance of that sea) is fourteen leagues one-third. Saseno is divided lengthwise by a range of seven hills, of which one rises to an elevation sufficient to contradict the epithet humilis, assigned to it by Lucan (Pharsalia, V. 650); unless he be supposed to compare it with the mountains on the continent, distant however above a league. While the Venetians possessed the adjoining continent Saseno was inhabited, and the walls of a ruined church assisted in protecting our tent. On the east side of the hills are considerable fragments of a brick structure, probably of the Augustan age. After a delay of six days in a very uncomfortable situation, especially considering the rude, we may say ferocious character of the Albanian shepherds on the island, a heavy fall of rain terminated the gale, and we proceeded on our voyage along the inhospitable Ceraunian coast, truly characterized by Horace:

"_________th’ Acroceraunian rocks

For frequent shipwrecks infamous."This part of the coast is, however, interesting in as far as relates to the final contest between Caesar and Pompey: for on it landed the former from Brundusium, in pursuit of his antagonist, when the dissensions in the Roman state had at last induced an appeal to arms.

Calms and the setting of the currents into the gulf of Valona, compelled us to use our great oars to draw off from the land, so that I could not make the remarks on the coast which I had projected. I resolved therefore to return at another time to survey that country as much as possible by land. I could, however, see that, for eight leagues from Cape Linguetta, the Acroceraunian coast presented only a range of barren mountains, absolutely deserted, excepting in winter, when it is visited by a few goat-herds with their flocks, who retire in spring, abandoning the country to vultures and reptiles of various sorts. The only vegetable productions seemed to be a few stunted pines and thorns.

In the evening of the 31st of January 1806, the south-east wind again setting in, we stood out to sea until we came near to Fano, the Othonos of antiquity, and the supposed abode of Calypso, celebrated in the Odyssee of Homer and the Telemachus of Fenelon. Fano, then occupied by the Russians, is situated in north lat. 39 deg. 50 min. 2 sec. and east long. from Greenwich 19 deg. 19 min. 50 sec. It is distant fourteen and one-third marine leagues, very nearly due-east from Cape St. Maria, the southernmost extremity of the heel of Italy, in north lat. 39 deg. 47 min. 30 sec. and east long. 18 deg. 23 min. 20 sec. Being placed in the middle of the fairway into the gulf of Venice, the accurate ascertainment of the position of Fano is an object of no small importance to mariners of all nations. Returning to the coast we were carried by the currents back nearly to the place where we had left it; and taking to our oars we continued our course to the southward. We soon came in front of a broad torrent from the mountains, called by the Italian seamen Strada bianco, a translation of the Epirote name Aspri rouga, the white way. A mile to the southward we had a view of Palæassa [Palasa], the representative of Palæste, where Cæsar landed his legions when in pursuit of Pompey, as related in the third hook of his Commentaries of the Civil War. Three miles farther on we came before Drimadez [Dhërmi], a small town situated in the midst of precipices and fragments of rock, through which shoot out a few pitch pines. A mile to the east I remarked the chapel of St. Theodore, on the summit of an eminence surrounded by olive-trees. This tract of the coast, though not very lofty, was steep over the sea, which our line showed to be from fifty-five to seventy-four English fathoms deep in various places, not far from the land. The ground consisted of coral rock. The highest part of the Ceraunian mountains we then estimated to exceed 700 toises, or 746 fathoms, or 4,476 feet in elevation above the sea. It was covered with snow, through which appeared broad lines of dark green firs. Beyond St. Theodore half a mile, opened into the sea a river which never runs dry, in a deep rocky channel; and a mile farther we doubled a point of land, which on the north-west covers the creek and road of Vouno [Vuno], now little frequented. A league more to the southward brought us opposite to Chimara [Himara], which has succeeded to the antique Chimæra, and now gives name to the district of the formidable Chimariotes. Chimara, as our interpreter told us, still stood out against Aly of Janina, as did all the villages of its district. The side of the hill on which the town is seated, broken into terraces, terminates on the shore in a white beach, to the southward of which is the bay of Gonea, which receives the waters, as I was informed, of what was styled the Royal Fountain. Two miles beyond Gonea we came before a tract of sandy beach, where fishing-boats are usually drawn up. This beach is probably formed by the waters of the river Phoenix, which, rising in the upper mountains, hurries down to the sea over precipices, forming numerous cascades, of which advantage is taken to draw off water to several mills on the banks. The Phoenix is now called the river of Chimara, as passing by that town; and two miles farther on the coast is the road or bay of Spilea [Spileja], formerly protected by two towers, but now containing only some decayed storehouses. Night was now coming on; the wind freshened; and we were within sight of Corfu, occupied by the Russians: it was therefore with no small satisfaction that we at last discovered the white tower of Palermo, and at six in the evening of the 1st of February we entered the bay. Being recognized by Aly's officer in the tower, he saluted us, not with guns, but with musketry, which we did not understand, and therefore kept over to the north shore. There, on the other hand, we were assailed by the Chimariotes with sharp rounds of musket-ball, which however did no harm. Returning again to the south shore, we came to anchor near the tower, and received a visit from the commandant, who for a month past had been in attendance, to welcome us on the part of his master. Having accepted his invitation to sup and sleep in the tower, or fort, he entertained us with a sheep roasted whole, and maize bread baked under the ashes; our drink was drawn from a skin of turpentined wine, and a tinned goblet served every guest in his turn. Our beds were the straw mats, neither new nor clean, on which we sat at our meal.

Porto Palermo, Fortress of Ali Pasha

(Photo: Robert Elsie, June 2001)The bay or port of Palermo [Porto Palermo] is in circuit about five miles; having an opening of a quarter of a mile in breadth between rocky points on which the sea beats with violence. The bay might therefore be well secured against an attack from without. The depth of water varies from five to twenty fathoms; but in one spot near Aly's tower, we found it seventy-five fathoms. The ground is said to be in general rocky: but as the bay abounds with fish of the stationary as well as of the migratory kinds, that information is probably erroneous. On all sides it is surrounded by high mountains, from which occasionally proceed severe squalls of wind: but in several parts vessels may be moored with perfect safety. The tower or fort stands on the southern point of the entrance, connected with the continent by a low narrow isthmus. It consists of a square with bastions, having a few guns, of no service either to command the entrance or to protect the shipping at anchor. Near it are some warehouses, a custom-house, and a Greek church. Upon the whole, the bay or port of Palermo might, in ancient times, and even at present, be properly denominated Panormos; for in one part of it or another vessels might be well secured against the sea.

Acroceraunia, or the Mountainous Region of Chimara

It was already said that the state of the weather did not permit me to survey the coast of Acroceraunia from the sea, with that minute care which it was a special object of my mission to employ. After I had been fully established in my official station with Aly in Janina therefore, I obtained permission and means of protection, to enable me to visit that and other regions of his territory, hitherto very imperfectly known, and indeed scarcely accessible by strangers. My survey of Acroceraunia was not all performed at one visit. Laying aside therefore at present the correct chronological order of my observations, I shall condense the whole into one continued narrative; connecting it with my remarks during my voyage along the coast. This will be more satisfactory to the reader than to be obliged to recur to the same scenes at different times, in the order of the periods when my observations were made.The Acroceraunian, or more properly the Ceraunian mountains, were so named by the ancients, from the Greek term keraunos, signifying thunder; because, from their elevation, and particularly from their position on the sea, they were much exposed, and frequently observed to be struck by lightning. Their northern extremity, the proper Acroceraunium on the bay of Valona, is situated in north lat. 40 deg. 26 min. 15 sec. and in east long. 19 deg. 14 min. 30 sec. The southern extremity of the country (not of the mountains which extend towards Butrinto) is at Port Palermo, of which the entrance lies in north lat. 40 deg. 2 min. 45 sec. and in east long. 19 deg. 48 min. 40 sec. The line of coast along the Adriatic therefore extends from north-west to south-east twelve marine leagues. Ceraunia is the country supposed by some commentators to be indicated by Circe in her instructions to Ulysses, where he was to find Aornos, there to invoke the shade of Tiresias, to consult him respecting his ultimate proceedings. If Homer selected the mountains of Chimara for the scene of infernal intercourse, on account of the pestilential vapours with which, in his day, they abounded, things must have greatly changed in the course of three thousand years. For, in the present time, no part of the coast of Epirus possesses air of greater purity and salubrity than the western slopes of the mountains of Chimara. In that clear atmosphere are found examples of longevity much more frequent and remarkable than in any neighbouring districts. But the advantages of health and long life enjoyed by the Chimariotes are more than compensated by the nature and appearance of the country allotted to them. Naked mountains intersected by tremendous gulfs and inaccessible precipices announce a region of incurable sterility. But these precipices and gulfs and rocks are regarded by the natives as their main defence against all enemies. Hence the insuperable attachment of the Chimariote to his native deserts, in whatever quarter of the world his fortune may lead him to pass his days. The internal parts of Acroceraunia are of a description much more attractive to the husbandman.

From Port Palermo to the town of Chimara the natives reckon an hour's journey on foot: but the coasting-barks count five miles along the shore to the landing-place belonging to the town. At that place landed my brother when he came to join me at Janina in March 1807; and to him I owe many of the observations introduced in this work on the whole coast of Albania northward to Durazzo and the river Drino. From the beach he mounted for half a league, by an artificial sloping road, up to the town of Chimara, where he discovered no vestiges of antiquity: but in the neighbourhood is to be seen an inclosure, evidently of very great age, probably the remains of the Chimaæra of Homer, near which Pliny places the Royal Fountain. This ancient fortification is named by the natives "the old castle of the queen," on account of the coins frequently found in it, bearing the figure of a female, with a Pegasus on the reverse; emblems generally ascribed to Apollonia farther north on the coast. The queen alluded to by the Chimariotes was perhaps the princess Anna Comnena, who mentions Chimara in her history of the contest between her father Alexis and the Normans, in the end of the eleventh century. On the overthrow of the old city the surviving inhabitants founded the present Chimara, containing about 500 families, all Christians. Two leagues farther to the north-west is Vouno, occupied by 1,200 Christians, near to a level tract on the side of the mountain, remarkable for its fertility, the probable site of some town; but no vestiges have been discovered. An hour's journey beyond Vouno, on the left, is the village Liates, and a league and a half farther on, over a succession of torrents and ravines, is Drimadez, seated on the heights, where the inhabitants point out a well of excellent water, a valuable treasure in such a country, and which may perhaps be the royal fountain of antiquity. From the town a rapid torrent rushes down the precipices to the sea. From Drimadez to Palæassa the distance is a league, and from the latter village to the sea the distance is four miles. The name of Palæassa recalls the Palæste of Cæsar, where his troops were landed on this coast, when pursuing his antagonist Pompey. But the "quiet station for ships amidst the rocks and other dangers of the Ceraunian coast," mentioned in the Commentaries (B. Civ. III. 6.) is not so obvious: nor does Palæassa offer any antique monument. A league and a half north-west from that place is the torrent of Strada bianca, or Rouga aspri, formerly noticed, beyond which is the bay and road of Daorso, called by the Italians Val d'Orso. On a height near the shore is an inclosure of the most remote, or what is termed Pelasgic construction: but still no rocky haven is there to be discovered. A league still farther northward, however, is Condami, a port sheltered and commodious, when once vessels have got within the shoals and sandbanks. There Cæsar might well have landed his troops; for during the eight years in which the French occupied Corfu, that station was constantly resorted to by their seamen, to watch the motions of the British cruizers in the entrance of the Adriatic. The distance from Palæassa to this haven is certainly considerable; but Cæsar may have considered the port as belonging to Palæste, as being within its territory and knowing no other designation for it.

The eastern or inland portion of Acroceraunia is now called Japoria, a corruption of the Japygia of Epirus, so named by colonies from the Japygia of Italy. In order to penetrate into this portion from Palæassa, you ascend for half a league to the summit of Mount Tchica [Çika], and then descend north-north-east for an equal distance in a valley through which runs a stream, which, passing by Ducates [Dukat], falls into the bay of Valona near Porto Raguseo. The ancient proper name of this stream is unknown to me; but it is probably the Salnich of the later geographers. From thence in an hour and a half, the traveller arrives on the broad summit of the lofty stormy Mount Longara [Lungara]; the only vegetation consisting in a few sweet acorns, the rhamnus paliurus, and the evergreen oak, which produces the kermes used in dyeing scarlet. North from the summit, five leagues through the mountains is Ducates, the capital of a small independent tribe, wholly addicted to robbery and plunder. The inhabitants of the place, composing 250 families Christian and Mahometan, live in a state of ferocity, violence, and barbarism, of which it is impossible to form a conception. Although they pretend to certain forms and usages of religion, yet, their morals are of the most debased character. They cultivate a little maize only; for to raise wheat or any other grain, would require more labour and time than they will bestow. Cattle also they possess; but they are ignorant of the art of separating the cheese from the butter, which they keep in skins. Necessity alone compels them to manufacture the rude coarse cloth of the natural wool, with which they are clothed; and the genius of evil has suggested to them the art of producing gun-powder, which is made in almost every family for its own use. As the Ducatians live only to rob and assassinate, so they labour the ground solely for their own consumption. Yet it is singular that they have never, like the Mainotes of the south of Peloponesus, or the pirates of the gulf of Volo in the north of Greece, ventured to extend their depredations on the sea. If ever the Ducatians turn their eyes towards the Adriatic, it is only to discover whether any vessel has been driven on their shores, that they may aid in her destruction, and plunder and massacre the unhappy crew. A league and a-half north from Ducates are found the ruins of Oricum, still called Ric or Deric, a place of great antiquity, and, on account of its harbour, of importance in all periods of Grecian history. The inhabitants and garrison placed in the town by Pompey, voluntarily submitted to Cæsar, who, in the exercise of his characteristic celerity, traversed the rugged Ceraunian mountains, and arrived before the place in the evening of the very day in which he landed in the bay of Palæste. A peculiar evidence of the position of Oricum still exists in the box-trees, which grow on the mountains of Ducates behind its site; the only quarter of all that coast in which that tree is found; and the box of Oricum is celebrated by various ancient authors. Although Oricum be now no more, the haven is still frequented and known among the Greeks, by the Italian name Porto Raguseo: by the Turks it is called Liman-padisha, or the imperial port. It is the most spacious and commodious in the bay of Valona, and the only station for ships-of-war between the bay of Cataro and the mouth of the Adriatic. A league north-east from Ducates, a stream crosses the path, which dries up in summer, and mounting up for a league more you come to Dragiates [Tragjas], a Christian village on the slope of a hill, commanding a view of the bay of Valona. The intervening ground, in breadth five miles to the sea, is cultivated and cheerful, on to the entrance of a deep narrow pass on the south-east, opening into a valley which widens in the direction of the river Voioussa [Vjosa], the Aous of antiquity. Going round the coast of the bay, at a league's distance north-east from Dragiates is Radima [Radhima], belonging to the district of Canina [Kanina], and the first village in the country of Musachia [Myzeqeja], the Taulantia of former times. A league and a-half farther is Mavrova, now rich in flocks, but formerly rich by its sea-marshes, producing salt of an excellent quality and colour. Nearly another league farther on is Crio-nero [Ujë i ftohtë], a place so named from a noted fountain, where ships resorting to that part of the bay take in water, which is rare on that coast. Three quarters of a league beyond Crio-nero, along the plain, is the fortress of Canina, built on a rock; and half a league farther you arrive at Valona. This town, the Aulon of former times, is still called Avlon by the Greeks, whence the Italians, by prefixing their article, have formed La Valona. It is situated half a league from the shore, and by the arcades under the houses, which line the streets, and other characters, announce the residence of the Venetians in former times. Near the town are the remains of two forts, blown up when they were compelled to surrender the place to the Turks in 1691. While in the power of the Venetians, Avlon was a place of considerable trade: but now it contains only about 6,000 inhabitants, Mahometans, Christians, and Jews; the latter banished from Ancona by Pope Paul IV. It is no longer counted among the episcopal sees of the east. The environs of the town, covered with olives, intermingled with country-seats and sepulchres, are bounded by a range of gypseous hills, from which issues the Artatus, which, having filled the ditches of the citadel, falls into the bay on the north of the rocks and fortress of Canina. So unwholesome are the vapours from the adjoining marshes, that the town is deserted by the inhabitants in summer; a few Jews only remaining behind; and parties of Christians in the environs, to cultivate the maize and the rice sown in the low grounds. That part of the district of Avion or Valona, which stretches for eight miles northward to the river Aous, now Voioussa, is not less fertile nor less unhealthy than the immediate environs of the town.

Three hours' journey towards the north-east, brings the traveller from Valona into the district of Coudessi, comprehending a portion of the ancient territory of Apollonia, and the celebrated mines or quarries of bitumen, applied to all the purposes of vegetable pitch. The bitumen is found in the angle formed by the influx of the Suchista [Shushica] into the Voioussa, on its left or south side. The beds of bitumen seem to reach to a considerable distance towards the south-east, and might furnish a sufficiency of pitch to supply all Europe. In the environs of the mines is found abundance of sulphur, combined with various substances, never yet satisfactorily analysed. The country-people report that, almost every night, bluish flames are seen to hover on the surface of the ground; a circumstance noticed by Aristotle and other ancient writers, and indicating the Nymphæum described by Plutarch in his life of Sylla. "Near Apollonia, (six leagues south-east,) is situated the Nymphæum, a consecrated place, whence perpetual springs of fire flow forth, without consuming the herb in the midst of a verdant valley and pasture." But the streams of fire, the inflammation of the incense offered to the nymphs of the springs, the oracular responses are no longer known by the oppressed Musachians, who dig the bitumen from the ground. The Suchista, which may contend with the river of Argyro-Castron for the name of Celydnus, rises in the mountains ten leagues to the southward. Near Nivitza Malisiotes, (Nivitza of the mountains,) on the course of the Suchista, are seen the remains of the ancient Amantia; distant, according to Scylax, 320 Greek stades or thirty-two miles from Apollonia. This space agrees with the present road; for from the remains of that city, up the Voioussa to the influx of the Suchista, is a distance of eighteen miles; and thence fourteen miles along the latter river reach up to Nivitza or Amantia. Below Nivitza, on the Suchista, stands Coudessi, the chief place of the valley and district; and a league and a half south from the bitumen-mines is situated Carbonara [Karbunar], on a bend of the Voioussa. On the right or north-east bank of this river, nearly opposite to Carbonara, on an eminence are the vestiges of an ancient city now called Gradista [Gradishta]; but which I am inclined to think belong to Byllis or Bullis. The remains are spread over a space of three miles in circuit. I perceived among them walls, constructed in the Pelasgian or most antique manner, but repaired with Greek and Roman work. In tracing the foundations of the suburbs, without the ramparts, I discovered the vestiges of a theatre, and the cella or body of a temple. Near this ruin, on the face of a rock, was a Latin inscription in which could be read the word BVLLIDEM, which left me in no doubt that I had found the Bullis of history; a town which, with Apollonia, Amantia, occupied by the partisans of Pompey, and the whole littoral tract of Epirus, voluntarily submitted to Caesar when he landed on the coast. Bullis is indeed styled a maritime town: but when the Voioussa is in the fulness of its stream, ancient ships might mount up so far. It is besides situated on the coast of the Adriatic, with respect to the great range of mountains which occupy the interior of the country, separating Epirus from Macedonia.

Four leagues up the left or south bank of the Voioussa, is Lunetzi, near which village are the remains of a fort, erected by the Latins in their wars with the Greeks in the middle ages. Three leagues higher up is Liopesi [Lap-Martalloz?], and a league to the southward is the bridge over the river Bentcha [Bënça], near the ruins of St. Severina, now called by the Albanians the Castle of Jarre; half a league still higher up stands Tebelen [Tepelena], the birth-place and favourite palace and treasure-house of Aly of Janina. In a journey undertaken by his desire, from Tebelen across Acroceraunia, in the direction of Port Palermo; a tract of country altogether unvisited by strangers, and indeed into which the people of the neighbouring tracts rarely venture to penetrate; I discovered near to Cosmari [Gusmar], the Roman road which led from Apollonia by Bullis and Amantia to Buthrotum. From the highest point of this road went off branches pointing towards the positions of Oricum, Palæste, and Panormus. In surveying this tract, it was Aly's purpose, to restore the Roman road, in order to obtain access to the forests of ship and house-timber in the environs of Cosmari. Circumstances however obliged me to quit Epirus before my survey was terminated. Nor could I discover the silver mines in the same district, in ancient times so rich, of which I had seen specimens in Aly's hands and had found a few in the torrents which descended from the mountains. To say the truth, I should have been very unwilling to disclose the situation of those mines, to add to the sufferings of the already oppressed people, by labouring to feed that insatiable desire of riches, by which Aly is incessantly agitated. The country of Acroceraunia produces wheat, barley, lupins, vetches, but in small quantities; for the inhabitants live wholly on maize. Their exports are wool, wax, kermes, fir, deals, pitch, firewood for Corfu, butter made of ewe milk; and with the money, in return, are procured the few foreign wares they need. The remainder of the money, such is the state of confidence amongst themselves, is buried in some secret place, and frequently wholly lost by the death of the owner. Along the sea-coast are found the usual vegetable productions of such a latitude; in the upper vallies, the slopes are clothed with pine and fir, maple, hasle, box: but in the plains along the Voioussa, are seen fruitful arable lands and plentiful pastures. Still the farmer, the shepherd, the peasant, have all a manifest air of misery, if not of poverty, the natural fruits of the tyrannical dominion, and the unsocial manners by which the country is borne down. The inhabitants, dreading to seem to be rich, rather than for its preservation, bury the greatest portion of their grain in ambaria or granaries dug deep in the ground. All ranks of men, without distinction, are constantly loaded with arms of various sorts; and their countenances openly declare the deplorable state of alarm and mutual distrust in which they pass their days.

Coast of Albania, from the Voioussa or Aous, north to the Drino or Drilo, by which it is separated from the Country of Scutari or Scodra. — Apollonia. — Berat. — Rivers Aous, Apsus, Genusus. — Durazzo. — Croia. — Alessio

Availing myself of the liberty assumed in the opening of the preceding chapter, I shall here combine my topographical remarks on the coast, from the Voioussa to the Drino, without regard to the chronological order of the several parts of the survey. With my own observations on this portion of Albania, I shall also combine those of my brother, who landed at the custom-house of Valona or Peloros, as that town is called by the Albanians. Proceeding for eight miles northward over the fertile but unhealthy plains of Valona, he arrived on the south bank of the Aous, now the Voioussa. On the opposite bank of the river, stood the handsome village of Fierè [Fier], and a mile to the westward was the monastery of the Virgin of Pollini, on the site of the antique Apollonia, the sole inhabited spot of the soil once sacred to Apollo. “Behold the monuments of the city, founded by the golden-locked Apollo, towards the borders of the Ionian sea.” Such, according to Pausanias, (Eliac. v. 22.) was the inscription engraved in ancient characters on the pedestal of the statue of the god of day. By a church surrounded by some monastic cells, and the whole inclosed by walls, furnishing accommodation for twelve monks, is now represented the once great and venerable Apollonia, a favourite city of Julius Caesar, and the chosen place of education of his grand-nephew Augustus. The era of the devastation of this celebrated city is unknown. The name is unnoticed in the writings of Anna Comnena, in the close of the eleventh century, and in every other Byzantine historian; although that princess, in describing the military operations of her father Alexis and the Normans, had frequent occasion to mention the Voioussa under its present name, and the towns on both sides of Apollonia. A bishop of this Apollonia, however, appears in the council of Chalcedon held in 451. It is first mentioned under the corrupted name of Pollina, by Castaldus, three centuries ago. It is amazing, but it is true, that it is equally impossible to ascertain the inclosure or limits of the city, which, we learn from Strabo and other writers, began at sixty stades, (seven and-a-half Roman or seven English miles,) up from the sea at the mouth of the Voioussa, where is now the dangerous harbour of Poros [Poroja]; and ten stades (one and-a-quarter Roman or one and an eighth English mile,) from the north bank of the river. Within the space certainly occupied by Apollonia, are to be seen eminences consisting of broken columns, friezes and capitals, with bricks on which are marked the number of the Roman legions by which they were made. The words "Philip Amyntas farewell," indicate the adorned monument of some Greek of distinction. On an adjoining height stands a single column of the Doric order; nearly thirteen English feet in circumference, and in other respects suited to the proportions of that simple order. This is the only part still erect of a temple 128 English feet in length by fifty in breadth. Among the ruins of this edifice was dug up, in 1813, a statue of Diana; and some years earlier was discovered, in the same place, a bas-relief representing Apollo mounted in a car drawn by the Hours, a scene introduced by Poussin in one of his pictures. The numerous medals discovered in the ruins of the city have almost always the laureated head of Apollo, with a cornucopia, vine-leaves and grapes. Cornalines have also been found, representing Apollo with his lyre. Such is the desolation of a city, once the renowned abode of science and wisdom; the resort of all who courted instruction: but now visited by rude Albanian shepherds alone, in their migrations with their flocks, between the mountains of Candavia and the plains of the Adriatic.

The Voioussa is traversed in a ferry-boat, between the caravanserails erected on each bank. For several days no passage had been practicable across the river, when my brother arrived at the ferry, on account of the floods: it was therefore with the greatest difficulty that he effected his passage. From the stony bank of the Voioussa the road for Berat, on the Apsus of antiquity, twenty-eight miles up from the sea, leads for half a league across a plain, covered with sabine and agnus castus, shrubs which abound in all the flat moist lands of Albania. Thence it enters a tract of cultivated ground a league broad. The next league traverses a range of meadow-pastures, which stretch westward towards the sea. In all that extent of plain the eye discovers only some knolls crowned with the huts of the wandering tribes, who guard the sheep and cattle, assisted by dogs of the most ferocious description; a race which abound all along the eastern coasts of the Adriatic. In the same plains are raised a race of horses, the finest for shape and swiftness of any produced in European Turkey. From time to time the traveller also falls in with camps of Tzingari, or gypsies, who seem to consider the plains of Musachia (as this country is now called) as their native land. According to the proper inhabitants of the country the gypsies have been constantly resident in it for these eight centuries back. And it is observable, that this period coincides with the reign of the Greek Emperor Nicephorus, in which that unsocial and rejected class of men first appeared in the east. An hour and a half's journey beyond the pastures, in the midst of low hills, is a large village called Novesela [Novosela], where, notwithstanding the repeated but untrue relations of the hospitality of the orientals, my brother and his guides were obliged to employ force to obtain shelter from the heavy rain, in the cottage of a Christian Albanian. On going out of Novesela, the road leads along the sides of a valley watered by the Glenitza [Gjanica], which falls into the Apsus; and from an eminence may be traced the course of the latter river all the way westward to the sea. From the same eminence are seen the snowy summits of Mount Tomoros, six leagues eastward, and the winding course of the Apsus, which descends from the glaciers of that mountainous range. The Apsus is crossed by a stone-bridge constructed on a sort of natural piers of rock, out of one of which projects a fountain of excellent water, of great service to the people of the village, when the river is troubled by the rains, or the melting of the snow. From this bridge downwards to the sea, a course of sixteen miles, the Apsus is called Ergent, or Argent: Anna Comnena, and some other writers of the Byzantine history, call it Charzanes. From the bridge upwards to Berat, a distance of twelve miles, the Apsus is called Beratino. The castle of Berat is perceived from a great distance, being seated on the summit of a hill, very high indeed, but commanded by another summit near it, on which another work has been raised for the protection of the castle. In the back-ground is the range of Mount Tomoros. The walls of the castle form a sort of parallelogram 512 yards in length, with flanking bastions, where the ground has permitted them to be constructed. But the strength of the castle consists chiefly in its position, on a lofty summit of rock nearly perpendicular, where it impends over the Apsus, or Beratino. This inclosure certainly formed the strong city built by Theodosius the younger, in the beginning of the fifth century, and named Pulcheriopolis, in honour of his sister Pulcheria. Being taken by the Bulgarians, they translated the name into their own equivalent Beligrad. By the Turks the town was styled Arnaut-Beligrad, to distinguish it from the important city Belgrade, on the Danube: now it is called Berat. Within the walls are the seraglio, or palace of the vizir or governor, and 250 houses inhabited by Albanians of the Greek church. The lower town is a straggling place in a deep bottom, seldom free from thick fogs, rising off the Apsus, which divides it into two parts; both inhabited by about 6,000 people, of whom one-third at most are Mahometans. In the town are several wealthy landed proprietors, and some merchants who resort to the ports and fairs of Italy. The governor or vizir, in my brother's time, was Ibrahim Pasha, two of whose daughters were the wives of two of Aly's sons, Mouctar and Veli. These alliances were not, however, sufficient to secure Ibrahim from the hatred and machinations of Aly, who at last made him his prisoner, and shut him up for life in a dungeon in Janina. Berat has the rank of an archiepiscopal see in the Greek church; but the archbishop resides in Moschopolis, or Voschopolis [Voskopoja], once an important, but now a decayed town in the Gueorcha [Korça], or Candavian mountains, near the sources of the Apsus.

Here the reader must be warned that my personal observations on the low coasts of the Adriatic must terminate. What is added respecting the tracts between the rivers Apsus and Drilo, near Scutari [Shkodra], is the result of information carefully collected from inhabitants and other persons, equally competent and trust-worthy, with whom I found means to open and maintain intercourse, generally personal, notwithstanding the hostilities carrying on between the pashas of Janina and Berat, during the years of my residence in Epirus. The most recluse parts of the mountains and forests were the usual scenes of our intercourse; and as far as notices collected in such a way, by a person not unpracticed in similar investigations, can be satisfactory, the reader may rely on their accuracy.

Continuing the journey northward to Durazzo, the celebrated Dyrrachium of Cæsar and Pompey, the road from Berat traverses the spacious and fertile plains of Musachia, watered by the Apsus, or Argent, which, in its very irregular course to the sea, scoops out for itself every year new channels, and forms new islands, from the trees, rocks, and gravel hurried down by the torrents and melted snows of Mount Tomoros. The western or maritime part of Musachia is termed Maille-castrat [Malakastra], signifying in the Albanian language "camps situated on eminences;" in allusion probably to the camps of Cæsar and Pompey, of which the remains may be traced on the banks of the Apsus. This conjecture naturally springs from a view of the ground.

From Berat a carriage-road is opened over the plain, varied however, by cultivated low hills for eight miles to Grabova, on a river which falls into the Apsus. Half a league beyond Grabova is a khan or inn, frequented by the fishermen employed on the lake Treboutchi, and by those who deal in the salt drawn from the vicinity of Meschino on the coast. Farther on is Daulas, a village preserving the remains and the name of Daulia, distant in a right line four leagues to the north-west of Berat; but erroneously placed by Ptolemy on the river Aous. Continuing his route the traveller arrives on the bank of the river Genusus, called by the Albanians Tobi, by the modern Greeks Scombi, and by the Byzantine historians Scombos. Springing from several sources in the Candavian range the Genusus traverses in its whole length the valley of Elbassan, and passing through the district of Pekini [Peqin] falls into the Adriatic. Very justly does Lucan notice the rapidity of this river, when he says that

"First saw the Romans met in hostile camps

The land which Genusus, with headlong tide,

And gentler Apsus, fit for barks, inclose."

Pharsal. V. 461If the Apsus were navigable from the sea in Lucan's time, great changes must have occurred in its embouchure, now quite inaccessible through sands and shoals. Perhaps the poet mistook that river for the Aous.

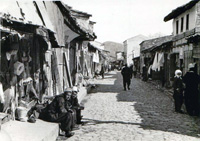

Bazaar in Elbassan

(Photo: Dayrell Oakley-Hill, 1930s)At the distance of nineteen miles up from the sea, in the valley of the Genusus, stands Elbassan, the successor of Albanopolis, a town first mentioned by Ptolemy in the second century. Situated on the north bank of the river, under a branch of the Candavian mountains, which separates that valley from the valley of Trana or Tyranna [Tirana], on the north; Albanopolis must always have been one of the most important places in Macedonian Illyricum. Such, under proper regulation and discipline, might still be the present Elbassan. Placed in a valley of great natural fertility, watered by the rapid though very winding Genusus, abounding in trees of various sorts, scattered over the meadows and pastures, and fully inhabited in a number of villages, notwithstanding the political evils of the town, it still retains a portion of its due value. A romantic and picturesque country, a pure and wholesome climate, every natural advantage, empower the inhabitants to lead a life of tranquillity and comfort; would they only renounce their predatory habits, and apply themselves to agriculture and commerce. That industry and its blessings are the objects pursued by the people of Elbassan, the stranger would naturally be induced to conclude, from the external appearance of the valley: but if he raise his eyes to the inclosing ranges of hills, a long line of towers and fortified posts, planted on the least accessible pinnacles, will announce to him the wretched state of hostility and alarm in which the unhappy Elbassanians pass their lives. Sentinels, small parties, and detachments of warriors, posted in those towers, watch over the lower grounds, to give notice of the appearance and approach of the surrounding tribes, against whom they are perpetually in arms. At the first signal of danger every man is ready for the field; and this state of apprehension and agitation, more injurious than the actual but occasional warfare of European nations, has had a most malignant effect on the population. Hence, instead of the 8,000 families or 40,000 inhabitants, formerly reckoned in Elbassan itself, the whole people of the town do not exceed 4,000 beings, distinguished even in that country by their ferocity and poverty. This wretched condition, the never-failing consequence of misgovernment, far from tempering the conduct of the Turkish lords of the valley, only embitters their natural brutality, and renders them unjust and cruel to the Greek Christians, borne down under their tyrannical yoke. The envy and hatred, natural in the heart of the Mahometans, rankle with double violence at the sight of a Christian Greek, more favoured by nature than themselves. A well-garnished mustachio, flowing ringlets of hair, handsome features, provoke the malignity of a decrepit Aga, enraged that heaven should bestow such graces on a race of beings born only to cringe and serve. Hence it is that the Raia (1) stoops as he walks, with his eyes on the ground, in the presence of the lordly Turks; halts when they approach, dismounts as they pass by; happy if the tyrant content himself with disdaining to notice him. Such is the condition of the Christians, in their original native land, in which they can acquire no real property, whom the vilest Turk may insult, and outrage with impunity. Should he even shed the Christian's blood, the assassin is sure of protection from the judge; should the relatives be so imprudent as to complain; for he also is governed by the same national fanatical prejudices, against all whom he regards as infidels.

The position of Elbassan is most favourable for commercial intercourse, for it commands the most commodious opening over the Candavian Mountains, on the most direct road between the Adriatic and the gulf of Thessalonica. It is distant twelve leagues north from Berat; ten leagues south from Croia [Kruja]; eighteen leagues west from Ochrida; and twelve leagues east from Durazzo; which formerly was, and still might be made a convenient port. But ideas and projects of renovation or even of preservation, never enter the heads of Turkish administrators. The rulers of Elbassan content themselves with collecting the revenue of the eight districts attached to it; supplying, by exorbitancy and extortion, all deficiencies. For their objects are only two; to purchase protection by bribes among the members of the Divan of Constantinople, and to pass their time in their government, in idleness, sloth, and voluptuousness. The population of the pashalik, or government of Elbassan, is estimated at 14,000 families, or 70,000 persons. The revenue is reckoned about half a million of Turkish piastres, or 25,000 l. In time of war, 7,000 men may be armed; counting one for every Mahometan family. The products of the country are wheat, maize, oil, wine, fruit, among which the quinces are of a prodigious size. But the principal riches of the people consist in their flocks and herds, and in a breed of mountain-horses of extraordinary fleetness. Seven miles up the course of the Genusus, from the sea, is Pekini, the chief place of a district called Scauria, by the historians of Scanderbeg. The inhabitants are all Christians, excepting those of Pekini itself, which is distant three and-a-quarter leagues from Cavailha [Kavaja], and five from Durazzo, both to the northward.

Having crossed the dangerous ford of the Genusus, (Scombi or Tobi), for the only bridges are in the valley of Elbassan, a course of an hour and-a-half brings the traveller opposite to Bosti, a large village on the slope of a range of hills, which run northwards to the valley of the river Drino. To the westward are seen the Adriatic and its inhospitable shores, with a few towers and villages. Towards Bosti, are numerous hamlets and extensive olive-grounds. The deep furrows of the cultivated lands evince the strength of the vegetable soil, and the peasants by their stature and vigour declare themselves to be those intrepid Guegues, the boast of Albanian warriors. In that quarter all have a rude ferocious mien; all are in arras: the women themselves, disdaining the veil or the spindle, are never seen without a pair of overgrown pistols or other arms. Every thing there, indeed, announces the extreme barbarism of the inhabitants. A league beyond Bosti, leaving Courtchiari in the same line, the road conducts, after three miles more, to Cavailha before-mentioned, a small town built on an eminence, connected with the hills which extend eastward to the Candavian range of mountains. Cavailha, as was already said, is distant three and-a-quarter leagues from Pekini, seven from Elbassan, six from Tyranna, and three from Durazzo: the town contains nothing worthy of the attention of the traveller. The district under the government of a voivode and a cadi contains thirty-five Mahometan villages, and forty-six inhabited by Christians, of the Latin or Roman church. These last, however, do not exceed 6,000 persons, while the former amount to 12,500, besides the colbans or shepherds. These colbans wander over the country, from mountain to mountain, free from all tribute or tax, and repair to the towns and villages, only for the purpose of exchanging their property for such few articles as they require. The territory of Cavailha is fertile and productive.

From Cavailha, two roads lead to Scutari [Shkodra] or Iscodar, formerly Scodra, the capital of Gentius king of Illyricum, and now of the sangiak or government of Upper Albania or Guegaria: it is situated at the southern extremity of the Lacus Labeatis, where its waters are discharged by the river Boiana [Buna], the ancient Barbana. One of these roads goes straight northwards in the direction, and on the vestiges of a Roman way. The causey or pavement may be traced at intervals on to Seraso. But as the torrents from the hills have greatly injured the road, it is seldom employed, excepting in summer when the marshes may be traversed in safety, or by the caravans of merchants having business in the valley of Croia. In other times of the year, travellers who employ relays of post-horses, (menzil-hané) take the road from Cavailha to Durazzo, and then follow the coast on to Alessio, the representative of the Lissus of antiquity, on the Drino. At twenty minutes journey north-west from Cavailha, the traveller comes to the Ululeus now Spirnatza, a small stream which rises in Mount Eridanus, now called Mount Iscamp, still preserving the name of Scampes, a town mentioned in the Roman Itineraries. Having forded the Spirnatza, which dries up in summer, the road points due-north for five miles; and on the right are many villages, shepherds' tents, and long ranges of forest of oak, fit for ship-building. Then bearing to the westward for a league you enter Durazzo, the capital of a district, subject to a vaivode. No town in this quarter of Illyricum has been more frequently noticed than Durazzo, under its former names of Epidamnus and Dyrrachium. But the two most memorable epochs of its history, are those of the contest between Cæsar and Pompey, forty-eight years before our era, and of the Greek Emperor Alexis, and the Normans under Robert Guiscard, in the end of the eleventh century. Of the former operations the only satisfactory and authentic relation is found in the third book of Cæsar's Commentaries of the civil war of Rome: of the latter in the Alexiade, or history of her father, written by the Princess Anna Comnena. Converted into a Roman colony by Augustus Durazzo became the ecclesiastical metropolis of all Illyricum, and was erected into a duchy by the Emperor Michael. Taken and occupied by the Normans, and again subdued by Bajazet II.; severely afflicted at different periods by earthquakes, sieges, and wars; Durazzo still preserves considerable evidences of its former grandeur. The walls, inclosing the original town, as well as the fortifications, constructed when it was enlarged, may still be traced. This double inclosure existed in the end of the eleventh century; for Anna Comnina states that Robert Guiscard, while besieging Durazzo, as it existed in his days, occupied a position within the ruins of the antique Epidamnus. Both towns were built on a promontory, advancing into the Adriatic, and beaten by its waves; against which shipping in the port, though a place of great resort, had no other defence than a very insecure anchorage. In this manner is Dyrrachium described by Lucan in his Pharsalia, vi. 22, &c.

"A fortress this, invincible by steel:

'Tis nature's work alone. It's strong defence

The rugged cliffs, that spurn the dashing surge.

A slender neck it to the land conjoins;

On rocks, the seaman's terror, rise the walls.

The fierce Ionian gulf, when Auster storms,

Temples and palaces in foam involves."The present Durazzo, built on the ruins of Dyrrachium, of which the remains, are frequently discovered, is surrounded with a wall mounted with cannon, all in the Turkish fashion; and containing 400 Mahometan families, commanded by a vaivode, at the head of a corps, of Janissaries. By that vis inertiae, that resistance to change, which still maintains the Ottoman empire in existence, Durazzo, like all the other Turkish towns on the coast of Greece, continues to be numbered among the fortresses of the grand-seignior. But it is also like too many of such towns, the theatre of insubordination and confusion, a nest of pirates, a den of assassins, and the polluted receptacle of criminals who escape from the shores of Italy. On the outside of this modern Poneropolis, (city of the wicked; a name assigned to Philippopolis of Thrace, because many of the first inhabitants had been guilty of sacrilege,) is a varochi, or suburb, occupied by 600 Roman Catholic families. Their church, under the invocation of St. Roch, was repaired in 1809, by means of contributions, collected under the authority of a French general in the country. The edifice, originally erected by the Normans in the twelfth century, was the see of the Latin Archbishop of Durazzo. But through the persecutions of the Turks, the present incumbent was compelled, at the hazard of his life, to relinquish his place and withdraw to Corbina, in the adjoining pashalik or government of Croia. There he has taken refuge near the Mirdites, a tribe, who, while they preserve inviolate their fidelity to the Ottoman government, have also resolutely defended their Christian profession and their civil rights, against the tyranny, spiritual and temporal, of their Mussulman rulers. The revenue drawn from the three voivodeliks or districts of Durazzo, Cavailha, and Pekini, which are farmed out in Constantinople for 400 purses, or 8,400 l., (a purse being twenty guineas,) is computed to exceed three times that sum, through the exorbitant operations of the beys in office. From the port of Durazzo the Sclavonians from the northward draw corn, oil, tobacco, Turkey-leather, and timber. In exchange they furnish scarlet-cloth, serge, steel, glass, and fire-arms, from the manufactory of Brescia, in the north of Italy.

In going from Durazzo to Scutari, you return on the road from Cavailha, for above two miles, to the edge of a marsh, which is crossed in its narrowest part on a decayed wooden bridge. This marshy lake is formed, not by the Apsus, as some writers, misunderstanding Lucan, have supposed, but by the waters of the Spirnatza or Ululeus; which in winter inundate the low grounds; but in summer the ground becomes sufficiently dry to allow maize to be sown and reaped. Beyond the marsh, the road winds for a league and-a-quarter to the river Lisana or Isanus [Lana], over which a Roman bridge is still sufficiently entire for use; and above five leagues farther is the river Matis [Mat], called by the Greeks Madia, but by the Albanians Bregoui-Matousi. There begins the district of Croia [Kruja], called by the Byzantine historians Croas, but by the Turks Ak-serail, the white palace. This town, situated on a hill of difficult access, was founded in 1388 by the chief of the district then called Scouria, now that of Pekini, on both sides 9f the Genusus. By its position Croia was secure from any sudden effectual attack; and by its abundant springs of water, from which it acquired its name, the town could not easily be reduced. Its chief renown, however, arises from the heroic and patriotic exploits of George Castriote or Scanderbeg, of whose states Croia was the capital. Although much decayed, the town still contains 1,200 Turkish families. Of 100 villages under its jurisdiction, sixty are occupied by Christians of the Roman church, under the Bishop of Alessio. The revenue of the pasha amounts to 300 purses or 6,300 l. and he would willingly augment it: but the warlike habits and reputation of the people have hitherto restrained him within reasonable bounds. The Mirdites, already mentioned, inhabit a multitude of villages, spread over the fertile valley of the Matis, twenty-four leagues in extent from the sea to its springs: their chief place, Orocher [Orosh], is distant sixteen leagues from Alessio. Two leagues up the river from the sea, is situated Ischmid, in the tract of country called the Red Plain, mentioned in the adventures of Scanderbeg. The road to Scutari traverses a forest two leagues in extent, following the tract of a Roman way, which leads to the bank of the Drino, a little above Alessio. Here ends Macedonian Illyricum; and here ends my description of the north of Greece along the coast of the Adriatic. I now return to Port Palermo, to continue the journey to Janina.

Route from Port Palermo by Delvino to Janina. — Excursion from Delvino to Butrinto, the ancient Buthrotum

On the 1st of February 1806, we arrived in the bay of Port Palermo, and on the following morning we commenced our journey to Janina, the residence of Aly. Our baggage was sent on before us, and at two in the morning we mounted our horses, accompanied by the boulouk-bashi, or commandant, heartily tired of his post, and in the hope of obtaining some mark of his master's favour, through our testimony of his good services and attention. Recommending therefore to the people of the place the care of the fortress, but in a special manner the care of his sheep and goats, he took the lead of our caravan. Climbing up the mountains which cover the bay on the south, we directed our course to the south-east; our horses, although bred to similar paths, having no small difficulty to pursue their course among the sharp rocks. The country seemed, as far as the moon enabled me to discover, to be wholly desert, only a few plants of the euphorbia, or prickly-pear, shooting up among the rocks. After an hour's progress we descended into a deep wooded valley, containing some sheep-folds, guarded by shepherds fully armed, and by dogs of the Albanian race, which assailed us with inconceivable fury. Our road then led for 200 yards through a gallery opened in the solid rock, and turned east, over a tract of land supported by ranges of dry stone-walls, to retain the water abundantly employed in the cultivation of maize. Soon after we came to the shore, at a vast height over the water, where was a watch-tower, inclosed by groups of shepherds round their fires.

Our guides foreseeing an approaching storm we pushed forward away from the coast, over a very rugged tract to the river Epari, which we luckily found low enough to be forded. The storm now in fact came on; the moon disappeared, and the lightning, which flashed with incessant vigour, alone pointed out our path. Confused by the gleams, however, we missed our way, and wandered about until, by the dashing of the waves, we found that we were again on the brink of a precipice over the sea. The rain pouring down in torrents; we alighted for safety; but after some time we discovered the entrance of the valley of Borchi [Borsh]. Fording the river which the people call Hadgi-agas-potami, then hurrying along, trees torn off by the violence of the rain, we mounted up half a mile to a khan or inn, defended by a tower occupied by a party of Albanians. After some questions we were admitted by people, who were Christians; and a plentiful wood-fire, lighted from the lamp always burning before the picture of the Virgin, with some maize-bread and brandy, soon restored us to a comfortable state. Notwithstanding all their attention, I could perceive that our guides and postillions seemed full of apprehension. Every motion and look of the Chimariotes was watched with peculiar care; and I concluded that we were in a post of the mountain-robbers. It must, however, be acknowledged that we received all attention and service with good-will from the suspected mountaineers, as far as their means enabled them. When day appeared I went out of the khan to view the country. The town of Borchi is placed at the west end of a fertile valley, which reaches east two leagues up the country, abounding in olive and other good trees. A torrent rushed down to the beach, where a number of fishing-boats lay a-ground. In front lay Corfu; to the west and north-west I saw Fano and Merlere, with three Russian men-of-war at anchor within a mile of the tower. Our whole night's journey had not exceeded ten miles; and it was our purpose to reach Delvino in the evening: we therefore set off early. Proceeding for a mile along the beach we came to the valley of Paron, but the village lies a league up the country; riding at times up to the saddle in the sea; and three miles farther we came to the valley of Pikerni [Piqeras]. The intervening hills were covered with lentiscus or mastick-trees, laurel, vallona oaks, &c. From one eminence I observed a vast fall of water, forming a succession of five cascades, down the face of a mountain clothed with pines. The rain had now ceased, the air was clear, and our attendants made the hills resound with their songs, in honour of the high martial deeds of their master Aly. I observed, however, that their voices gradually fell as we drew near to Loucovo [Lukova], a small town, of which the inhabitants might probably have answered in a manner any thing but complimentary to that hero. Loucovo is situated on the round summit of a well cultivated hill. The slopes towards the sea are laid out in terraces, ornamented with fruit-trees and other valuable vegetable productions; the whole appearing an Eden in the eyes of persons emerging from the rude barren wilds of Acroceraunia. The inhabitants forming 400 families of Christians, lately subdued by Aly, manifested an appearance of prosperity and comfort, far from common among the peasantry of Epirus. On the sight of Aly's people the Loucovians shut their doors; the peasants of Corfu, who pass over every year to labour on the continent, retired from the fields as we drew near; and we could bear, as we passed along the streets, certain expressions of vengeance, to which our guides thought it proper to yield a deaf ear.

From Borchi to Loucovo is a course of seven miles; and on leaving the last place we entered on a region offering a melancholy contrast with that we had just left. Nothing is to be seen but a naked plain covered with stones and slate, intermingled with stunted bushes of kermes-oak and paliurus. To the north and east the view was bounded by ranges of lofty mountains loaded with snow: but our course was to the south-south-east for a league, following the tract of blood from animals recently devoured by the wolves. Half a league farther we descended to a deep torrent, a mile beyond which I saw a country-house of Aly just built, in the midst of Oudessovo, a village destroyed by him in 1798. The impression made by that destruction seemed unabated in the mind of a papas or Greek priest, who spoke to us on the subject. From this place we mounted four miles south by east, to the summit of a mountain, where we found a fountain, and a portion of a paved road, ascribed by the peasants to Bajazet Ilderim, but which may with greater probability be regarded as a work of the Romans; being a continuation of the way which, traversing Acroceraunia from north to south, passed by Phanoté and Cassiopia to Nicopolis, on the gulf of Prevesa, founded by Augustus, in memory of his final victory over Antony and Cleopatra. Four hundred yards farther we arrived near the ruined village Agios Vasili (Saint Basil). On the hill behind the village ruins are said to be discovered near the chapel of Panagia Kronia, (the Virgin of Cronia) a name which perhaps bears some allusion to a temple sacred to Saturn. There we found a sort of fortress, regarded by the Albanians, and for some time by Aly himself, as the key of the Ceraunian mountains. Seating ourselves in the sun against a wall, we dried our clothes, and took our repast, whilst our horses were refreshed. Round the fort a new village of fifty Christian families promised to become a place of importance. Two miles beyond St. Basil we saw on the right Nivitza-Bouba [Nivicë-Bubar], a village reviving from its ashes; and the adjoining coast throws out a promontory, Kephali, into the channel of Corfu. From this place we followed an ancient causey, broken through in several places by the torrents, for a league and a half. The country around seemed deserted by the inhabitants, for we could discover only the pyramidal huts of the shepherds. When we had proceeded half a mile from this causey or paved road, repaired at different periods by the Turks, we went down into the valley of Delvino [Delvina], in which we forded the Pavla (Paula) often very dangerous for passengers. This river, which descends from Mount Tchoraides, in the southern slopes of Acroceraunia, runs in general from north to south, and discharges its waters into the lake Pelois, now the Vivari, at Butrinto. Nearly a mile beyond the river we saw, on our route south-south-east across a plain, an aqueduct of modern construction, but broken by the floods, and near it a ruined chapel; beyond which 400 yards, we halted under the shade of a plane-tree, reckoned to be one of the noblest trees of Epirus.

Aly's officer in our company desired us to halt there until he should procure information concerning the state of Delvino, and whether war or peace prevailed in the country; an advice in which we the more readily acquiesced, because we heard several smart discharges of musketry on the hills to the southward. About sun-set our spy returned with the information that Aly's troops were masters of the town, and that consequently we might go forward. To prevent, however, any possible inconvenience from those disorderly bands, he brought with him the country dresses in which M. Bessières and I disguised ourselves, and advanced to Delvino, distant a mile. There was still light enough to exhibit the beauty of the situation and scenery of the town: but on ascending an eminence on the north side I discovered, in a hollow below me, the devastation produced by the soldiers of Aly, who had set fire to the bazar or market-house, in order to conceal the thefts they had committed in it. The cries of the sufferers were heard at a distance, and the flames illuminated that part of the town where we were to be lodged, in the house of a bey, a partizan of Aly; a house destitute of furniture, and open to every wind. Supper was, however, provided for us, in which proper care had been employed that we should not be exposed to suffer from repletion; and our beds were duly adapted to our repast. Such a moment, it will readily be conceived, was far from favourable to my exploratory purposes: the following observations on Delvino, the river Pavla, and Butrinto, were therefore collected in the course of a posterior tour. Delvino reckons scarcely 600 houses, scattered over a space of a league in extent, on the slopes of several hills, which, covered by plantations of olive, lemon, and pomegranate-trees, afford views of singular beauty. In the midst is a hollow, containing the bazar and the varochi, or suburb of the Christians, in which is the humble mansion of the Bishop of Chimara and Delvino. The castle is seated on a detached height, accessible by a single very narrow path, bordered by precipices; it commands the hollow ground of the bazar, through which runs a stream, which above two miles off falls into the Pavla. The hills on the east of the town are adorned with a number of pleasant houses; but the adjoining plain is open and bare. Two leagues to the west, on the sea-shore, in the village Lycouria, are seen the remains of Onchesmus, or Anchiasmus, consisting of some ancient Greek tombs and fragments of architecture. The town was destroyed by the Goths under Totila about 552, along with many others on the coast of Greece. About a league to the north of Delvino, among the hills, is a place called Palæa-Avli [Palavlia] (the old court) surrounded by olive-trees, of remarkable growth, on which account it is probably the successor of Elæus. For independently of the etymology of the ancient name, as alluding to olives, it has been remarked that those trees are never found at a greater distance than sixty geographic miles from the sea, or from some spacious lake. The fragments consist chiefly of foundations of walls of Cyclopian construction, without the least vestige of architecture, Greek or Roman. Elaeus had never therefore been restored after the horrible devastation inflicted by the renowned precursor of the Goths, Æmilius Paulus, who, in one day plundered and laid waste seventy cities of Epirus, and carried off 150,000 of the inhabitants.

The ruins of Finiq