| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

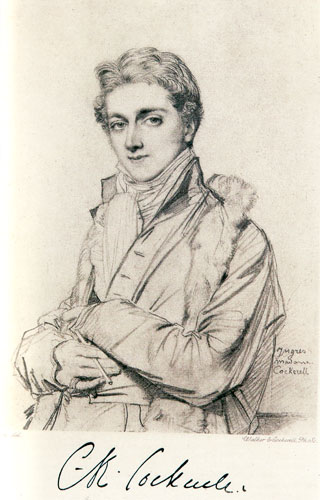

Charles Cockerell

(Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres,

1817)

1814

Charles Cockerell:

Travels in Southern EuropeCharles Robert Cockerell (1788-1863), born in London, was a British architect, archaeologist and writer who is remembered for his works of Georgian architecture in Britain and for his role in the excavation of the temples of Aegina and Bassae. From 1810 to 1817 he travelled extensively in Greece, Albania, Turkey and Italy. In 1819, he was leading architect of Saint Paul’s Cathedral in London and in later years was made President of the Royal Institute of British Architects. It was in January 1814, during his travels in Greece, that he ventured northwards to Albania (that began in Preveza) to visit the realm of Ali Pasha, where he made several vivid sketches. An account of this visit is given in his journal: “Travels in Southern Europe and the Levant, 1810-1817” (London 1903).

The Court of Ali PashaWith some difficulty got across to Previsa. Here the harbour is a fine one, but too shallow to admit large vessels, and with an awkward bar. The shore is all desolation and misery, with one exception, the palace of the vizier, which is splendid. The foundations on the side towards the sea are all of stones from Actium and the neighbouring San Pietro, the ancient Nicopolis.

In Venetian days Previsa had no fortifications. Now the pasha has made it quite a strong place, with several forts and a deep ditch across the isthmus, though the cannons, to be sure — which are old English. ones of all sorts and sizes — are in the worst possible order, their carriages ill-designed, and now rotten as well. The population has fallen from 16,000, to 5,000 at the outside, mostly Turks.

We went of course to Nicopolis. The ruins are most interesting. There are the theatre, the baths, the odeum, and the walls of the city, all in fair preservation and most instructive: the latter especially, as an example of ancient fortification. An aqueduct, which is immensely high, brought water from nine hours off.

We went from Previsa, in a scampa-via belonging to the vizier, to Salona, the port for Arta. It consists of only two houses, the Customs house and the serai of the vizier. In the latter we got lodgings for the night, and bespoke some returning caravan horses to carry us to Arta. The road, 25 feet wide, is one which has been lately made for the vizier by a wretched Cephaloniote engineer across otherwise impassable flats. It is not finished yet; 800 to 1,000 men are still at work upon it. There is no doubt that this road and the canal from Arta to Previsa, as well as the destruction of the Suliotes, who made this part of the world impassable to travellers without a large escort, are public benefits to be put to Ali Pasha’s credit.

Arta is a flourishing place under the special eye of the vizier. The bazaar is considerable, and there is every sign of industry.

We left it about midday. The ice was thick on the pools and the road hard with frost. Passing the bridge, we got again on to the vizier’s new road. The Cephaloniote superintendent, who was very desirous that we should express to the vizier great admiration for the work, was assiduous in doing the honours of it. After various stoppages, at last, at seven o’clock, nearly frozen, we reached the khan of Five Wells.

A rousing fire we made to warm ourselves by was no use, for it smoked so intolerably that it drove us out again to walk about in the cold till the room was clear. Our only distraction was a Tartar we fell in with who had lately been to Constantinople by land, and his account of the journey is enough to make one shudder.

He passed through no less than nineteen vilayets, or towns, in which the plague was raging. At Adrianople the smell of the dead was so great that his companion fell ill. At the next place he asked at the post if there was any pest. ‘A great deal, God be praised,’ was the reply. At another town, in answer to inquiries he was told ‘half the town is dead or fled, but God is great.’

What a miserable country!

Next day, riding along a paved way, we got to Janina or Joannina, the capital of Ali Pasha.

The first coup d’œil of the great town and the lake is certainly impressive, but not so much so as I had expected. Once inside the town the thing that struck me most was the splendid dress of all ranks and the shabby appearance we Franks presented.

We made for the house of our minister, George Foresti, with whom we dined, and there met Colonel Church, just arrived from Durazzo.

Next day, as the vizier wished to see us, and we of course to see him, Foresti took us to the palace he was living in for the moment. He has no less than eight in the town. This one is handsome, but the plan is as usual ill-contrived, and there was much less magnificence than I had expected.

We were first led into the upper apartments to await his leisure, and found there a number of fine youths, not very splendidly dressed. After half an hour of waiting we were led into a low room, in the corner of which sat this extraordinary man. He welcomed us politely and said he hoped we had had a good journey and would like Janina, and desired that if there was anything we lacked we would mention it, for that he regarded us as his children, and his house and family were at our disposal. He next asked if any of us spoke Greek; and hearing that I did, asked me when I had learnt it, and how long I had remained in Athens. Then, observing that Hughes was near the fire, he ordered in a screen in the shape of a large vessel of water, saying that young men did not require fire, only old men; and in saying this he laughed with so much bonhomie, his manner was so mild and paternal and so charming in its air of kindness and perfect openness, that I, remembering the blood-curdling stories told of him, could hardly believe my eyes. Finally, he said he hoped to improve our acquaintance, and begged us to stay on. We, however, bowed ourselves out.

The number and richness of the shops is surprising, and the bustle of business is such as I have not seen since leaving Constantinople. We understood that when the vizier first settled at Janina in ‘87 — that is, twenty-seven years ago — there were but five or six shops in the place: now there are more than 2,000. The city has immensely increased, and we passed through several quarters of the town which are entirely new.

The fortresses on the promontory into the lake are of the vizier’s building. He has always an establishment of 3,000 soldiers, 100 Tartars (the Sultan himself has but 200), a park of artillery presented him by the English, and German and other French artillerymen. We seem to have supplied him also with arms and ammunition in his wars with Suli and other parts of Epirus. Perhaps it is not much to our honour to have assisted a tyrant in dispossessing or exterminating the lawful owners of the soil, who only fought for their own liberty; but one must remember that, picturesque as they were and desperately as they fought, they were nothing but robbers and freebooters and the scourge of the country.

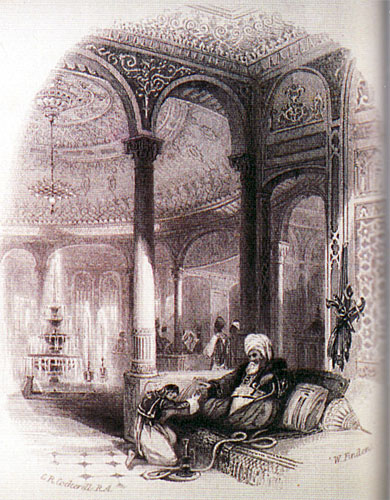

We passed the 6th of January with Psallida, who is master of a school in Janina, He is, for this country, a learned man. Besides Greek, he speaks Latin and very bad Italian, but as far as manners go he is a mere barbarian. From him I had an account of the Gardiki massacre. (1) I occupied a wet three days in drawing an interior view of a kiosk of the viziers at the Beshkey Gardens at the north end of the town. Then I got a costume and drew the figures in. Psallida dined with us one day and entertained us with an account of the fair and frail Euphrosyne, who was a celebrity here. Her fate was made the subject of a ballad preserved in Leslie. The story is certainly an awful tragedy. She was of good family and married to a respectable man. Without possessing more education than is usual with Greek ladies she had, besides her great beauty, a natural wit which, with a good deal of love of admiration, soon attracted round her a host of admirers, and she became a reigning beauty. Mukhtar, the son of Ali, who is a dissolute fellow, was attracted by her, and, cutting out his competitors, became her acknowledged lover. His wife, whom he entirely neglected for his new passion, was a daughter of the Vizier of Berat, whose friendship Ali was at that time particularly anxious to cultivate; and when she complained to her father-in-law of his son’s conduct, he (Ali) determined to put a stop to it. At the head of his guard he burst at midnight into the room of Euphrosyne, and after calling her the seducer of his son and other names, he forced her to give up whatever presents he had made her, and had her led off to prison with her maid. Next day, in order to make a terrifying example to check the immorality of the town in general and his son in especial, he had nine other women of known bad character arrested, and they and Euphrosyne were led to the brink of the precipice over the lake on which the fortress stands. Her faithful maid refused to desert her, and she and Euphrosyne, linked in each other’s arms, leapt together down the fatal rock, as did all the others.

Mukhtar has never forgotten his attachment or forgiven his father, or even seen his wife again, and from having been a gay and frank youth he has become gloomy and ferocious without being less dissolute than before. The court he keeps is a sad blackguard affair, a great contrast to the austere sobriety of his father’s.

We called in the evening (January 14) to take leave of Ali Pasha. He was on that day in the Palace of the Fortress at the extremity of the rock over the lake. We passed through the long gallery described by Byron, and into a low anteroom, from which we entered a very handsome apartment, very warm with a large fire in it, and with crimson sofas trimmed with gold lace. There was Ali, to-day a truly Oriental figure. He had a velvet cap, a prodigious fine cloak; he was smoking a long Persian pipe, and held a book in his hand. Foresti says he did this on purpose to show us he could read. Hanging beside him was a small gun magnificently set with diamonds, and a powder-horn; on his right hand also was a feather fan. To his left was a window looking into the courtyard, in which they were playing at the djerid, and in which nine horses stood tethered in their saddles and bridles, as though ready for instant use. I am told this is a piece of form or etiquette.

At first his reception seemed less cordial than before, whether by design or no, and he took very little notice of us. He showed us some leaden pieces of money, and a Spanish coin just found by some country people, and asked us what they were. Then he said he wished he had a coat of beaver such as he had seen on the Danube. He asked Parker whether he had a mother and brothers, and when he heard he was the only son he said it was a sin that he should leave his mother. Why did not he stay at home?

On January 15 we went to call on Mukhtar Pasha. We found him rough, open, and good-humoured, without any of the inimitable grace of his father, which makes everything Ali says agreeable, however trivial the subject may be. Mukhtar’s talk was flat. He was very fond of sport — were we? It was very hot in summer at Trikhala. He had killed so and so many birds; there were loose women at Dramishush; it was a small place, but he would send a man to see that we were properly accommodated; and so on — very civil and rather dull. He smoked a Persian pipe brought him by a beautiful boy very richly dressed, with his hair carefully combed, and another brought him coffee; while coffee and pipes were brought to us by particularly ugly ones. On the sofa beside him were laid out a number of snuff-boxes, mechanical singing birds, and things of that sort. The serai itself was handsome in point of expense, but in the miserable taste now in vogue in Constantinople. The decoration represented painted battle-pieces, sieges, fights between Turks and Cossacks, wild men, and abominations of that sort; while in the centre of the pediment is a pasha surrounded by his guard, and in front of them a couple of Greeks just hanged, as a suitable ornament for the palace of a despot.

On the 16th we set out early for an excursion to Cassiopeia and Suli, across the fine open field behind Janina, past the village of Kapshisda, over a low chain of hills south-west of Janina. Then, after a climb of over an hour, we entered a pass, and presently saw Dramishush in front, on the side of a high mountain.

Cassiopeia is on a gentle height in the middle of a valley. The situation is beautiful, and the theatre the largest and best preserved I have seen in Greece.

Next morning we dismissed Mukhtar Pasha’s man who had escorted us so far, and went on south-westwards along the edge of the valley of Cassiopeia. As it grew narrower we climbed a ridge which overhung an awful depth, went over a high mountain, and reached Bareatis, a small village in a pass with a serai of Ali Pasha’s, in which he lived for a length of time during the war of Suli. Three and a half hours further on we came to Terbisena, the first village of Suli. It had been pouring all day, and we were not only wet and cold when we arrived but the hovel we got as a lodging let in the water everywhere, and here, huddled in the driest corner we could find, we had to sleep and spend the next day.

On the 19th the weather was fine again, and we went on hoping to find the river fordable, but when we got to the bank we found it rapid and deep. One of our Turks, after a good deal of boasting, plunged in, and in an instant sank, and the torrent was carrying him and his horse floundering away. Another of his brother Turks, seeing him carried down, called loudly on Allah, and stroked his beard in great tribulation, but without stirring a stump. In another minute the man would have been drowned, but our servant Antonetti, who was but a Christian, very pluckily ran in and clawed him out. The poor boaster was already senseless when we got him to land. We took him back to Dervishina, and gradually brought him round, when instead of thanking his stars for his narrow escape, or Antonetti for the plucky part he had played, he did nothing but lament the loss of his gun, ‘Tofeki,’ which he had himself won, he said, and of his shawl which had cost him 50 piastres. We promised to make the latter good, and left him to rest.

The whole incident was in all senses a damper to our ardour. When we considered that to pass this river we must wait one day at least, and probably four days to get across the one near Suli, the expenditure of time seemed to us all, at least so I thought, greater than we cared to devote to the expedition. So the long and short of it was that we turned back and slept at Bareatis. Next day we got back to Janina. I made up my mind now that I was wasting time over this trip, and wished to get back to Athens. But before leaving I thought it my duty to call once more on Ali Pasha. A most agreeable old man he is. I was more than ever struck with the easy familiarity and perfect good humour of his manners. We found him in a low apartment with a fire in the middle, generally used for his Albanians and known as laapoda. Then we went to see Pouqueville, (2) the French resident. We found him with his brother, both of them the worst type of Frenchmen — vulgar, bragging, genuine children of the Revolution. Nothing worth remembering was said, but I did gather this from his tone — that the Empire in France is not likely to last.

On the 26th my friends, for a wonder, got up early, and we all set out in a boat for a small village where we were to find my horses. There we bid farewell and I mounted. It came on to rain, and I arrived, wet through, at the Three Khans to sleep.

Next day the rain became snow, but I set out nevertheless for Mezzovo. We had to ford the river several times, and for the last hour to Mezzovo were up to our middles in snow. The scenery was magnificent, and the country is well cultivated. Mezzovo is a Vlaki or Wallachian village; the people speak a sort of mixed Greek. They are exceedingly industrious and well-to-do.

Artistically I do not know that I have gained much, but I do not regret the time I have spent in Albania. The climate is more bracing than that of the rest of Greece, and has set me up after my illness. The scenery, though it cannot be at its best in winter, is most beautiful, and the inhabitants are a fine race— not handsome, but hardy and energetic. An Albanian has very few wants. A little bread of calambochi or Indian corn, an onion, and cheese is abundant fare to him. If he changes his linen five times in the year, that is the outside. A knife and a pistol in his girdle and his gun by his side, he sleeps quite well in the open air with his head on a stone and the lapel of his jacket over his face. In summer and winter he wears a fez. His boots are only goatskin sandals, which he makes himself. His activity in them over rocks is surprising.

As for Ali Pasha’s government, one has to remember what a chaotic state the country was in before he made himself master of it. The accounts one gets from the elders make it clear what misery there was. No stranger could travel in it, nor could the inhabitants themselves get about. Every valley was at war with its neighbour, and all were professional brigands. All this Ali has reduced to order. There is law — for everyone admits his impartiality as compared with that of rulers in other parts of Turkey — and there is commerce. He has made roads, fortified the borders, put down brigandage, and raised Albania into a power of some importance in Europe.

The Gardiki massacre took place about 1799. In Ali’s youth, his tower had been stormed by the people of Gardiki and his mother and sister outraged—at least, so he said. He nursed his revenge for forty years, and then gratified it by massacring the whole population of the village. Author of a valuable account of Greece at this time. [Extract from Charles Robert Cockerell: Travels in Southern Europe and the Levant, 1810-1817: the Journal of C. R. Cockerell, R. A. (London: Longsman, Green and Co., 1903, reprint London: Routledge & Thoemmes Press, London 1999), p. 232-245.]

TOP