| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

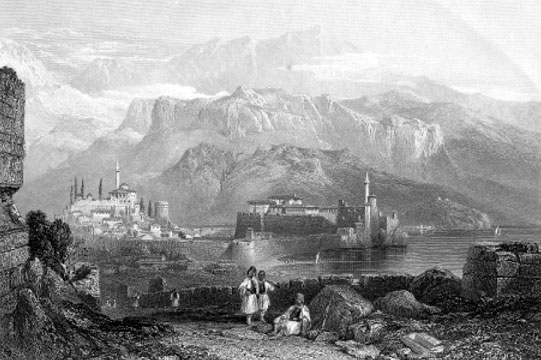

"Janina, the Capital of Albania,"

19th century engraving.

1830

Benjamin Disraeli:

Letter on a Visit to AlbaniaThe charismatic Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881) is remembered as one of the most colourful figures of British politics in the nineteenth century and was twice Prime Minister during the reign of Queen Victoria. He was also a well-known and much read author of Victorian prose. As a young man, Disraeli went on a grand tour of the Mediterranean and the Middle East, ostensibly for health reasons. This seventeen-month tour (from June 1830 to October 1831), which took him to Spain, Malta, Albania, Greece and the Middle East, proved to be one of the most formative experiences of his early years and one of the most vivid memories of his whole life. From Corfu, Disraeli and his two travelling companions travelled to Arta and Janina (Iôannina), then the capital of southern Albania under Ottoman rule, which Lord Byron had visited in the days of Ali Pasha Tepelena (1741-1822), the so-called Lion of Janina. Disraeli's official pretext for the journey into the wilds of Albania was to deliver a letter to the Grand Vizier from Sir Frederick Adam, the British Governor of the Ionian Isles. In Preveza, he reported, "I shall never forget the effect of the Muezzin, with his rich and solemn and sonorous voice, calling us to adore God in the midst of all this human havoc." He delighted in particular in the Albanian costumes. Much of what Disraeli saw and experienced in southern Albania was used in the Scanderbeg novel,"The Rise of Iskander," that he wrote in Bath two year after the Albanian tour. His letters from Albania convey the sense of awe he felt at entering the divan of the Great Turk. Here is one of them.

The young Disraeli

by Sir Francis Grant, 1852

My dearest Father,

I wrote to Ralph from Malta, and to you from Corfu, and left the letters to be forwarded by the October packet, when it arrived, if it ever did, of which to-day there is a report here. It was so late after its time that it was quite despaired of. Doubtless, however, you have received my letters by some source or other. I mentioned in my letter to you, that there was a possibility of our paying the Grand Vizier a visit at his quarters at Yanina, the capital of Albania. What was then probable has since become certain. We sailed from Corfu to this place, where we arrived on the eleventh instant, and found a most hospitable and agreeable friend in the Consul General, Mr. Meyer, to whom Sir Frederick had given me a very warm letter. He is a gentleman of the old school, who has moved in a good sphere, and has great diplomatic experience of the East. He insists upon our dining with him every day, and what is even still more remarkable, produces a cuisine which would not be despicable in London, but in this savage land of anarchy is indeed as surprising as it is agreeable.

As the movements of his Highness were very uncertain, we lost no time in commencing our journey to Yanina. We sailed up to Salora (I mention these places, because you will be always able to trace my route in your new maps), and on the morning of the 14th, a company of six horsemen, all armed, we set off for Arta, where we found accommodation ready for us, in a house belonging to the consulate. Arta, once a town as beautiful as its situation, is in ruins, whole streets razed to the ground, and, with the exception of the consulate house, rebuilt since, scarcely a tenement which was not a shell. Here for the first time I reposed upon a divan, and for the first time heard the muezzin from the minaret, a ceremony which is highly affecting when performed, as it usually is, by a rich and powerful voice. Next morning we paid a visit to Kalio Bey, the Governor, once the wealthiest, and now one of the most powerful, Albanian nobles. He has ever been faithful to the Porte, even during the recent insurrection, which was an affair of the great body of the aristocracy. We found him keeping his state, which, in spite of the surrounding desolation, was not contemptible, in something not much better than a large shed. I cannot describe to you the awe with which I first entered the divan of a great Turk, or the curious feelings with which, for the first time in my life, I found myself squatting an the right hand of a Bey, smoking an amber-mouthed chibouque, drinking coffee, and paying him compliments through an interpreter. He was a very handsome, stately man, grave but not dull, and remarkably mild and bland in his manner, which may perhaps be ascribed to a recent imprisonment in Russia, where, however, he was treated with great consideration, which he mentioned to us. He was exceedingly courteous, and would not let us depart, insisting upon our repeating our pipes, an unusual honour. At length we set off from Arta, with an Albanian of his bodyguard for an escort, ourselves and guides, six in number, and two Albanians, who took advantage of our company. All these Albanians are armed to the teeth, with daggers, pistols, and guns, invariably richly ornamented, and sometimes entirely inlaid with silver, even the tassel. This was our procession:

An Albanian of the Bey's guard, completely armed.

Turkish guides, with the baggage.

Three Beyasdeers Inglases, or sons of English Beys, armed after their fashion.

Giovanni, covered with mustachios and pistols.

Boy carrying a gazel.

An Albanian completely armed.

The gazel made a capital object, but gave us a great deal of trouble. In this fashion we journeyed over a wild mountain pass-a range of the ancient Pindus-and two hours before sunset, having completed only half our course in spite of all our exertions, we found ourselves at a vast but dilapidated khan as big as a Gothic castle, situated an a high range, and built as a sort of half-way house for travellers by Ali Pasha when his long, gracious, and unmolested reign had permitted him to turn this unrivalled country, which combines all the excellences of Southern Europe and Western Asia, to some of the purposes for which it is fitted. This khan had now been turned into a military post; and here we found a young bey, to whom Kalio had given us a letter in case of our stopping for an hour. He was a man of very pleasing exterior, but unluckily could not understand Giovanni's Greek, and had no interpreter. What was to be done? We could not go on, as there was not an inhabited place before Yanina; and here were we sitting before sunset on the same divan with our host, who had entered the place to receive us, and would not leave the room while we were there without the power of communicating an idea. We were in despair, and we were also very hungry, and could not therefore in the course of an hour or two plead fatigue as an excuse for sleep, for we were ravenous and anxious to know what prospect of food existed in this wild and desolate mansion. So we smoked. It is a great resource, but this wore out, and it was so ludicrous smoking, and looking at each other, and dying to talk, and then exchanging pipes by way of compliment, and then pressing our hand to our heart by way of thanks. The Bey sat in a corner, I unfortunately next, so I had the onus of mute attention; and Clay next to me, so he and M. could at least have an occasional joke, though of course we were too well-bred to exceed an occasional and irresistible observation. Clay wanted to play écarté, and with a grave face, as if we were at our devotions; but just as we were about commencing, it occurred to us that we had some brandy, and that we would offer our host a glass, as it might be a hint for what should follow to so vehement a schnaps. Mashallah! Had the effect only taken place 1830 years ago, instead of in the present age of scepticism, it would have been instantly voted a first-rate miracle. Our mild friend smacked his lips and instantly asked for another cup; we drank it in coffee cups. By the time that Meredith had returned, who had left the house on pretence of shooting, Clay, our host, and myself had despatched a bottle of brandy in quicker time and fairer proportions than I ever did a bottle of Burgundy, and were extremely gay. Then he would drink again with Meredith and ordered some figs, talking I must tell you all the time, indulging in the most graceful pantomime, examining our pistols, offering us his own golden ones for our inspection, and finally making out Giovanni's Greek enough to misunderstand most ludicrously every observation we communicated. But all was taken in good part, and I never met such a jolly fellow in the course of my life. In the meantime we were ravenous, for the dry, round, unsugary fig is a great whetter. At last we insisted upon Giovanni's communicating our wants and asking for bread. The Bey gravely bowed and said, 'Leave it to me; take no thought,' and nothing more occurred. We prepared ourselves for hungry dreams, when to our great delight a most capital supper was brought in, accompanied, to our great horror, by-wine. We ate, we drank, we ate with our fingers, we drank in a manner I never recollect. The wine was not bad, but if it had been poison we must drink; it was such a compliment for a Moslemin; we quaffed it in rivers. The Bey called for the brandy; he drank it all. The room turned round; the wild attendants who sat at our feet seemed dancing in strange and fantastic whirls; the Bey shook hands with me, he shouted English-I Greek. 'Very good' he had caught up from us. 'Kalo, kalo' was my rejoinder. He roared; I smacked him on the back. I remember no more. In the middle of the night I woke. I found myself sleeping on the divan, rolled up in its sacred carpet; the Bey had wisely reeled to the fire. The thirst I felt was like that of Dives. All were sleeping except two, who kept up during the night the great wood fire. I rose lightly, stepping over my sleeping companions, and the shining arms that here and there informed me that the dark mass wrapped up in a capote was a human being. I found Abraham's bosom in a flagon of water. I think I must have drunk a gallon at the draught. I looked at the wood fire and thought of the blazing blocks in the hall at Bradenham, asked myself whether I was indeed in the mountain fastness of an Albanian chief, and, shrugging my shoulders, went to bed and woke without a headache.

We left our jolly host with regret. I gave him my pipe as a memorial of having got tipsy together.

Next day, having crossed one more steep mountain pass, we descended into a vast plain, over which we journeyed for some hours, the country presenting the same mournful aspect, which I had too long observed: villages in ruins, and perfectly uninhabited, caravanseras deserted, fortresses razed to the ground, olive woods burnt up. So complete had been the work of destruction, that you often find your horse's course on the foundation of a village without being aware of it, and what at first appears the dry bed of a torrent, turns out to be the backbone of the skeleton of a ravaged town. At the end of the plain, immediately backed by very lofty mountains, and jutting into the beautiful lake that bears its name, we suddenly came upon the city of Yanina - suddenly, for a long tract of gradually rising ground had hitherto concealed it from our sight. At the distance we first beheld it, this city, once, if not the largest, one of the most prosperous and brilliant in the Turkish dominions, still looked imposing; but when we entered, I soon found that all preceding desolation had only been preparative to the vast scene of destruction now before me. We proceeded through a street, winding in its course, but of very great length, to our quarters. Ruined houses, mosques with their tower only standing, streets utterly razed-these are nothing. We met great patches of ruin a mile square, as if a swarm of locusts had had the power of desolating the works of man as well as those of God. The great heart of the city was a sea of ruin. Arches and pillars, isolated and shattered, still here and there jutting forth, breaking the uniformity of the desolation, and turning the horrible into the picturesque. The great bazaar, itself a little town, was burnt down only a few months since when an infuriate band of Albanian soldiers heard of the destruction of their chiefs by the Grand Vizier.

But while the city itself presented this mournful appearance, its other characteristics were anything but sad. At this moment a swarming population, arrayed in every possible and fanciful costume, buzzed and bustled in all directions. As we passed on-and you can easily believe not unobserved where no 'Mylorts Ingles' (as regular a word among the Turks as the French and Italians) had been seen for more than nine years-a thousand objects attracted my restless attention and roving eye. Everything was so strange and splendid, that for a moment I forgot that this was an extraordinary scene, even for the East, and gave up my fancy to a full credulity in the now obsolete magnificence of Oriental life. Military chieftains clothed in the most brilliant colours and most showy furs, and attended by a cortège of officers equally splendid, continually passed us; now for the first time a dervish saluted me, and now a Delhi with his high cap reined in his desperate steed, as the suite of some pacha blocked up the turning of the street. The Albanian costume, too, is inexhaustible in its combinations, and Jews and Greek priests must not be forgotten. It seemed to me that my first day in Turkey brought before me all the popular characteristics of which I had read, and which I expected I occasionally might see during a prolonged residence. I remember this very day I observed a Turkish sheik in his entirely green vestments; a scribe with his writing materials in his girdle; and a little old Greek physician, who afterwards claimed my acquaintance on the plea of being able to speak English, that is to say, he could count nine on his fingers, no further (literally a fact). I gazed with a strange mingled feeling of delight and wonder. Suddenly a strange, wild, unearthly drum is heard, and at the end of the street a huge camel (to me it seemed as large as an elephant) with a slave sitting cross-legged on neck and playing an immense kettle-drum, appears, and is the first of an apparently interminable procession of his Arabian brethren. The camels were very large, they moved slowly, and were many in number; I should think there might have been between sixty and a hundred. It was an imposing sight. All immediately hustled out of the way of the caravan, and seemed to shrink under the sound of the wild drum. This procession bore corn for the Vizier's troops encamped without the wall.

It is in vain that I attempt to convey to you all that I saw and felt this wondrous week. To lionize and be a lion at the same time is a hard fate. When I walked out I was followed by a crowd; when I stopped to buy anything I was encompassed by a circle. How shall I convey to you an idea of all the Pachas, and all the Agahs, and all the Selictars, whom I have visited, and who have visited me; all the coffee I sipped, all the pipes I smoked, all the sweetmeats I devoured? But our grand presentation must not be omitted. An hour having been fixed for the audience, we repaired to the celebrated fortress-palace of Ali, which, though greatly battered in successive sieges, is still inhabitable, and yet affords a very fair idea of its old magnificence. Having passed the gates of the fortress, we found ourselves in a number of small streets, like those in the liberties of the Tower, or any other old castle, all full of life, stirring and excited; then we came to a grand place, in which on an ascent stands the Palace. We hurried through courts and corridors, all full of guards, and pages, and attendant chiefs, and in fact every species of Turkish population, for in these countries one head does everything, and we with our subdivision of labour and intelligent and responsible deputies have no idea of the labour of a Turkish Premier. At length we came to a vast, irregular apartment, serving as the immediate ante-chamber to the Hall of Audience. This was the finest thing I have ever yet seen. In the whole course of my life I never met anything so picturesque, and cannot expect to do so again. I do not attempt to describe it; but figure to yourself the largest chamber that you ever were perhaps in, full of the choicest groups of an Oriental population, each individual waiting by appointment for an audience, and probably about to wait for ever. In this room we remained, attended by the Austrian Consul who presented us, about ten minutes - too short a time. I never thought that I Gould have lived to have wished to kick my heels in a minister's ante-chamber. Suddenly we are summoned to the awful presence of the pillar of the Turkish Empire, the man who has the reputation of being the mainspring of the new system of regeneration, the renowned Redschid, an approved warrior, a consummate politician, unrivalled as a dissembler in a country where dissimulation is the principal portion of their moral culture.

The Hall was vast, built by Ali Pacha purposely to receive the largest Gobelins carpet that was ever made, which belonged to the chief chamber in Versailles, and was sold to him in the Revolution. It is entirely covered with gilding and arabesques. Here, squatted up on a corner of the large divan, I bowed with all the nonchalance of St. James's Street to a little ferocious-looking, shrivelled, care-worn man, plainly dressed, with a brow covered with wrinkles, and a countenance clouded with anxiety and thought. I entered the shed-like divan of the kind and comparatively insignificant Kalio Bey with a feeling of awe; I seated myself on the divan of the Grand Vizier ('who,' the Austrian Consul observed, 'has destroyed in the course of the last three months,' not in war, 'upwards of four thousand of my acquaintance') with the self-possession of a morning call. At a distance from us, in a group on his left hand, were his secretary and his immediate suite; the end of the saloon was lined by lacqueys in waiting, with an odd name which I now forget, and which you will find in the glossary of Anastasius. Some compliments now passed between us, and pipes and coffee were then brought by four of these lacqueys; then his Highness waved his hand, and in an instant the chamber was cleared. Our conversation I need not repeat. We congratulated him on the pacification of Albania. He rejoined, that the peace of the world was his only object, and the happiness of mankind his only wish: this went on for the usual time. He asked us no questions about ourselves or our country, as the other Turks did, but seemed quite overwhelmed with business, moody and anxious. While we were with him, three separate Tartars arrived with despatches. What a life, and what a slight chance for the gentlemen in the antechamber!

After the usual time we took our leave, and paid a visit to his son Amin Pacha, a youth of eighteen, but who looks ten years older, and who is Pacha of Yanina. He is the very reverse of his father, incapable in affairs, refined in his manners, plunged in debauchery and magnificent in his dress. Covered with gold and diamonds, he bowed to us with the ease of a Duke of Devonshire, said the English were the most polished of nations, etc. But all these visits must really be reserved till we meet. We found some Turks extremely intelligent, who really talk about Peter the Great, and all that, with considerable goût. With one of these, Mehemet Aga, Selictar to the Pacha of Lepanto, and an approved warrior, we became great friends. He showed us his new books of military tactics, and as he took a fancy to my costume insisted upon my calling to see his uniforms, which he gets made in Italy, and which really would not disgrace the 10th.

I forgot to tell you that with the united assistance of my English, Spanish, and fancy wardrobe, I sported a costume in Yanina which produced a most extraordinary effect on that costume-loving people. A great many Turks called on purpose to see it, but the little Greek physician who had passed a year at Pisa in his youth, nearly smoked me. 'Questo vestito Inglese o di fantasia?' he aptly asked. I oracularly replied, 'Inglese e fantastico.'

I write you this from that Ambracian Gulf where the soft Triumvir gained more glory by defeat than attends the victory of harsher warriors. The site is not unworthy of the beauty of Cleopatra. From the summit of the land this gulf appears like a vast lake walled in on all sides by mountains more or less distant. The dying glory of a Grecian eve bathes with warm light a thousand promontories and gentle bays, and infinite modulations of purple outline. Before me is Olympus, whose austere peak glitters yet in the sun; a bend of the land alone hides from me the Islands of Ulysses and of Sappho. When I gaze upon this scene I remember the barbaric splendour and turbulent existence which I have just quitted with disgust. I recur to the feelings in the indulgence of which I can alone find happiness, and from which an inexorable destiny seems resolved to shut me out.

Pray write regularly, as sooner or later I shall receive all your letters; and write fully. As I have no immediate mode of conveying this safely to England, I shall probably keep it in my portfolio till I get to Napoli, and send it through Mr. Dawkins.

A thousand loves to you all.

Your most affectionate,

B. D.Prevesa, October 25, 1830

[Letter X of 25 October 1830 by Benjamin Disraeli. From: Home Letters written by the late Earl of Beaconsfield in 1830 and 1831, published by Ralph Disraeli (London: John Murray 1885, reprint New York: Kraus Reprint 1970), pp. 75-95.]

TOP