| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1853

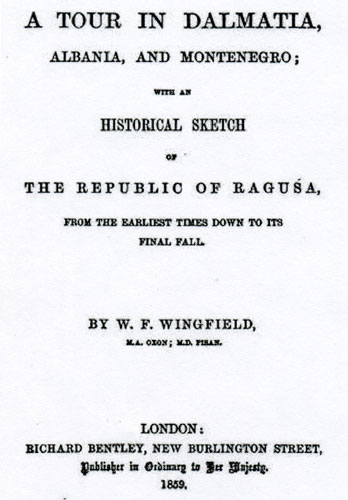

William Wingfield:

A Tour in AlbaniaDr William Frederick Wingfield (1813-1874) was an English author who toured the Adriatic coast in the mid-nineteenth century. He stemmed from Worcester and studied at Oxford. Wingfield seems to have been a Catholic theologian like his father, and is remembered for translations of the Roman Breviary, He lived in Austria for many years, including Piran (now in Slovenia) and Gorizia (now in Italy). In 1853, he travelled from Zagreb down the coast of Dalmatia to Albania. The trip is described in his only published work, “A Tour in Dalmatia, Albania and Montenegro, with an Historical Sketch of the Republic of Ragusa, from the Earliest Times Down to its Final Fall” (London 1859). In this book, given in the form of letters, he reports primarily on Ragusa (Dubrovnik) and the other towns of Dalmatia, and their history, but he also includes the account of his visit to Shkodra in Ottoman Albania, where he was interested in the situation of the Catholic population.

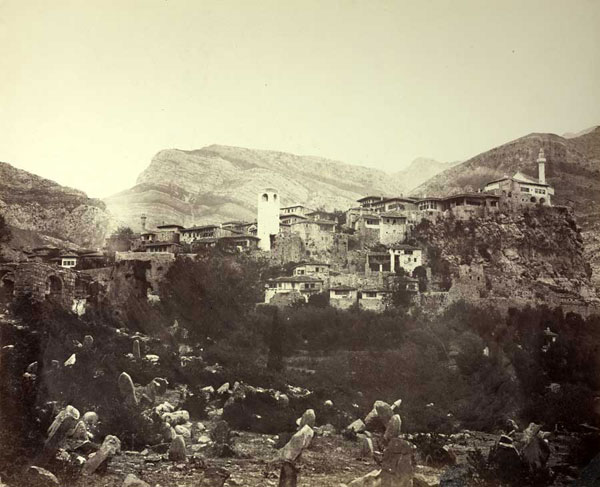

Antivari (Old Bar) in 1863

(Photo: Josef Székely,

ÖNB, Bildarchiv, Vienna,

VUES IV 41055)The following morning I started at seven with fresh horse and guide, this time an Albanian Catholic, for Scutari. The road we took ran first beneath the town, across the river, and then turned up the hill, on part of which Antivari is built, keeping along an elevated causeway of large, rough stones fitted together, which sometimes showed in its construction superior skill and workmanship, sometimes so badly repaired, that it was difficult for the horse which carried me to pass; especially since over the steeper acclivities it led in the form of flights of rough, irregular steps, leaving it evident that the engineer who planned it did not contemplate the use of wheeled carriages. This continued nearly the whole way to Scutari, except where it was interrupted by the infamous state of its repair, a grievance to the traveller of no recent date, for its course was obliterated in one part for a long way by old thorn-trees, which could only have commenced their slow growth after the beaten track had been effaced, and the wayfarer compelled to choose his path through the adjoining fields, amidst the mire of which we had to flounder for some half-mile before we could regain the stones.

Just as we started, and before we had well cleared the walls and suburbs of the town, but were quite out of sight of people, we were joined by two Turkish women in large dark capotes, the hoods drawn over their faces, and slippers on their bare feet. They, too, were going to Scutari, and wished to take advantage of our escort. Eventually they kept up with us the whole day, though, judging by the whiteness of their hands and feet, they could not have been accustomed to such long journeyings on foot, At first they walked behind us, closely veiled, with much apparent shyness; but the heat of the sun, and the severity of a protracted march along so rough a road, soon made them less coy. They dropped their veils, and, pulling off their slippers, took every natural means, according to the notions of the women of those countries, to help themselves along, including, by-the-bye, giving their cloaks to my horse to carry. Both were young and well-looking; the youngest quite a girl, of seventeen, perhaps; the other about ten years older. The day was fine, and the scenery lovely, through a fine wild champaign country, skirted, with woods, and the deep blue mountains rising above for the background. Of cultivation, except a patch of maize here and there, I could see none. A cow or two, and a few sheep, mixed with goats, fed in the rough fields, which were scattered, few and far between, along the roadside. The sheep, both black and white, and some horned, seemed to have tufts growing on their foreheads; their fleece elsewhere being long and ragged, between wool and hair, so that they looked like English, long-woolled doormats on legs. Though I saw no pomegranates on the hedges, as the day before yesterday, my “vetturino” — such was my guide’s proper appellative — brought me one of first-rate size and sweetness in the beginning of our march. I suspect it was garden-grown; but this fruit is renowned in the neighbourhood of Antivari. At Scutari they abound also, but of a harsh, rough-tasted sort. About mid-day we waded through a swollen brook, and, finding a nice piece of turf on the opposite bank, sat down, in three parties, to our respective dinners; that is to say, the Mussulman women in one place, my guide in another, and myself in a third. In half an hour we were again en route, and, as the shades of evening drew on, about six o’clock, p.m., reached a long wooden bridge across the wide river, along the side of which the road for the last hour or so had been winding. This river is the Drino, and here, where it runs out of the lake, is at least as wide as the Thames below Teddington. Beyond the bridge came the Bazaar, where I halted by myself for ten minutes, while my Vetturino went to escort the poor “ladies,” who were getting thoroughly knocked up, and had, besides, never been in Scutari before, to the Khan, where they were to pass the night. By this time it was dark; and when, for nearly another hour, we kept on still traversing the same kind of pavement as before, now between high walls, now among gravestones still seeing no houses, I at length inquired, with much naiveté, and to the guide’s no small amazement, when we should reach Scutari, and received for answer, to my no less astonishment, that it had been Scutari ever since we left the Bazaar! Where, then, were the houses? Low-roofed, and wide-spread, they were completely concealed from our ken, as we passed along, by their garden, or, more strictly speaking, orchard walls, within which each was enclosed. Thus widely does Scutari differ from Antivari; the latter remains as it was when a Christian town, but the former, cramped by no city walls, and arranged after Turkish notions, has all the air of an Oriental city transplanted into Europe. In short, I seemed to be always in the suburbs. And, as no artificial light from that glory of modern civilization, gas, or even from the more primitive lamp or candle, assisted the eye to dispel its illusion, so neither, though we were actually penetrating into a city of many thousand inhabitants, and the capital of a pashalic, did the ear reveal its proximity.

Nothing is more striking than the quiet and orderly, nay, silent state of a Turkish town at night. No voices of the eager buyer or the yet more ardent seller, do throng of passers-by in pursuit of business or pleasure, with their noisy footfalls; no theatres, no places of public resort, no cries, no clamour, no busy hum of men, that unfailing concomitant in all ages of our western cities. Nay, to its praise be it said, no haunts of ill-fame contaminate its products; no sounds of drunken revelry disturb its streets; no noisy brawls alarm its peaceful citizens. After nightfall the streets are empty; each family has retired to its own abode: and if any one appears in the public ways, it is a solitary person with a light, perhaps going to seek the doctor, or on some other errand of necessity or charity. A solemn stillness reigns, which is broken only by the guard going round to see that all is safe, and to remove, if haply they should fall in with such, any disorderly person, or even the idle wanderer, who ventures to roam abroad at such an hour without ostensible object.

The house we now entered differed nothing in plan from those I have already described at Antivari, except that it was larger, and stood in its own inclosure, as aforesaid, M. Bonatti, the Vice-Consul, received me in the usual sofa’d divan, and with much hospitality. He was a native of Corfu, and, though the representative of England in this place, spoke no English, nor yet French, but Italian only.

The next day it was necessary that I should attend the Pasha’s divan, more especially if I adhered to my determination to proceed over the lake to the frontier of Montenegro: an undertaking of no little difficulty, as some thought, since hostilities had already recommenced — if they could be said ever to have ceased — between the Turks and Montenegrins. But, whatever the difficulty, or even danger, no one doubted (in this every Consul was agreed) it would be less hazardous than the attempt, under present circumstances, to penetrate deeper into Albania or Bosnia. They said that the cry of war had excited a deep, fanatical hatred against all foreign Christians in the breast of the common Turk, who fancied that the present troubles, probably about to end in their expulsion from Europe, were the result of the information carried by Frankish spies concerning the nakedness of the land, and that a solitary foreigner, even an Englishman, would hardly be safe from violence in the more secluded, and therefore more grossly ignorant, parts of the country. The assassination of Christians, even of the richer class, is unhappily of no very rare occurrence. Thus, within a year, a Triestine merchant, named Salvare, who resided with the family near Durazzo, was shot dead as he was going into church on Sunday... the only conceivable motive of the crime being a fanatical hatred of his religion! So I was assured by his brother.

Accompanied, therefore, by M, Pericles Bonatti, the Vice-consul’s son, — the father was infirm, — I ascended by a rocky path the steep and high hill, on the top of which stands an ill-repaired and middle-age looking castle, of considerable extent, at once the residence and fortress of the Pasha. Externally, but little change seems to have taken place in it during the last four centuries; internally, however, a lofty minaret tower, with its Muezzin uttering from the little gallery at the top, which he walks round at the same time, his monotonous and melancholy call to prayer for mid-day (a devotion which, like the “Angelus” of the Catholic Church, is repeated at sunrise and sunset), and a large, low building, looking like barracks, but arranged as the rest of the houses here, indicate that it has been accommodated to the usages of its Turkish masters, who have possessed it ever since the days of the last of the Castriotts; i. e., long enough to compel some alteration, if only perforce of decay and the ravages of time. Two rather ill-looking fellows, in an attempt at uniform, stood as sentinels at the outer gate, and presented arms on our approach. Other soldiers loitered about through the yard in national costume, which, when complete, imparts a considerable display of offensive weapons — long gun, pistols, and hangjar — while a few dismounted rusty-looking cannon lay around. In the lobby, or open gallery leading to the Pasha’s divan, lounged a number of swarthy, fierce, but not very soldier-like men, some in uniform, others in more or less handsome national dress. The whole place had a free-and-easy barrack-like appearance. In an open room hard by, whither we went for a few minutes, sat a venerable old man before a writing-table. This was the Pasha’s treasurer, an Albanian Christian, who, as far as respectable looks go, easily bore the palm amongst the whole cortège. It struck one as remarkable, that that office should be committed to a Christian, amongst such strict Mussulmans. On catering the divan we found Osman Pasha, a civilised-looking gentleman, something above fifty, seated on one of the sofas, and dressed in European uniform, with boots so thin they seemed made for sofa wear, though their master did not sit cross-legged either on this occasion. His manners were courteous, and even high-bred. I may observe that he is descended from one of the most ancient families in Bosnia, once, of course, Christian, but long since apostatized to Islamism. His wife, to whom he has been married twenty years, and to whom popular rumour says he is devotedly attached, is of equal birth. Their matrimonial felicity is the more remarkable as they have no children. After the usual pipes and coffee, which were handsomely served in silver by black servants — slaves from Africa — we talked through an Italian dragoman (for the Pasha could not, or would not, condescend to speak any language but Turkish), and I requested permission to pass Lessandrovo, the last of their stations on the lake, on my road to Cetinja, the capital of Montenegro. “It is a little difficult,” he replied, “for we are again expecting trouble from those bestie” - that, however, at such a crisis as the present, nothing should be refused to an Englishman. Accordingly, his secretary was directed to draw up a firman to the Bey in command on the island of Lessandrovo, to which the Pasha’s seal was affixed; and I then took my leave. His Excellency also at the same time broke up his divan, and descended into the neighbouring plain to superintend some artillery practice, which, as well as the distribution of ammunition throughout all the neighbouring villages, was intended, I believe, as a demonstration to intimidate their unquiet neighbours, the Montenegrins, who were suspected of intending a renewal of their raids into the Pashalic.

Ruins of the mosque in the fortress

of Shkodra (Photo: Robert Elsie,

March 2008)

The rest of the day was spent in a visit to Monsignor Fra Giovanni Topic, bishop of Alessio and administrator of this diocese, and somewhat later to the Austrian Vice-consul, who spoke French, as well as Italian and German.

The cathedral of Scutari, the residence of so many thousand Christian, during so many centuries, too, stands in a small enclosure of its own, and would, I should think, contain twenty persons standing, certainly not more! On Sunday mornings the poor people crowd into the courtyard, happy if they may obtain a glimpse of the altar. I was assured that hitherto the Turkish authorities would not, on any account, concede more church-room or allow, even here, any external emblem of the Christian religion.

To those who are descended from the original Christians, the profession of their religion is allowed on payment of a yearly tax, or “tribute,” as it is called; but converts from Mahometanism are still liable to be punished with death. The same punishment is appointed to be inflicted on those who, after feigning to belong to the established religion, return to the profession of Christianity. This was quite recently exemplified in the case of two peasants, George and Antonia Craini, who stood in the relation of uncle and niece; the former being likewise guardian to the latter, through the premature death of her parents, and who, belonging to the “occult” Christians ( i.e., such as believe in Christ, but secretly, to escape the tribute), had been induced, by the exhortations of their bishop, to make open profession of their faith. They likewise hoped that, having paid a bribe of five hundred piastres, which had been accepted, they would escape the legal penalty. The affair, however, got wind, and was immediately taken up by the zealots. Both were seized, placed in irons, and imprisoned, he in the castle, she under the custody of the Zingari, or Gypsies, who in Albania have the charge of female prisoners. The man, after long torture with the tombuk and scourgings, made a pretended abjuration of Christianity, and was banished to Lessandrovo, to be kept there under surveillance; whence, however, he escaped into Montenegro, and thence proceeding to Cattaro, finally found a resting-place in Southern Albania, where, being in security, he, of course, renewed his profession of the Christian faith, In the meanwhile, his niece, Antonia, a girl of eighteen, and unmarried, remained in her jail, notwithstanding every effort on the part of the consuls and bishop, by representations to the local governor, and, through the ambassadors, to the authorities at Constantinople, to obtain her release. It was a particularly hard case, since she had been educated in Christianity without any consciousness of the fraud practised by her parents or guardians; and now, though imprisoned for six months, and tried by every species of threat and promise, accompanied with terror, steadfastly refused to renounce her faith. At length, after long suffering on her part, and a course of systematic evasion and shuffling on the part of Osman Pasha and those about him, she was finally liberated by the intervention of Omar Pasha, and allowed to rejoin her uncle amongst the Miriditi, a tribe of free Albanians, to one of whom she was engaged to be married.

[excerpt from: W. F. Wingfield: A Tour in Dalmatia, Albania and Montenegro, with an Historical Sketch of the Republic of Ragusa, from the Earliest Times Down to its Final Fall. London: Richard Bentley, 1859, p. 150-165]

TOP