| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

Georgina Mackenzie

Paulina Irby

1861

Georgina Mackenzie and Paulina Irby:

Travels in the Slavonic Provinces

of Turkey-in-EuropeGeorgina Muir Mackenzie (1833-1874) and Adeline Paulina Irby (1831-1911) travelled extensively through the lands of former Yugoslavia and Albania in the years 1861-1864. Georgina Mackenzie, the eldest child of a Scottish baronet from Delvine in Perthshire, set out with her travelling companion Paulina Irby, daughter of the English rear admiral, Baron Boston, from Lincolnshire, on an initial trip to Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1858. Troubles with the Austrian authorities sparked their interest in the lands of the southern Slavs which they subsequently visited on five extensive journeys. Their main interest was the lot of the Christian Slavs in the Ottoman Empire, and schooling for girls and women there. The travels are described in their 687-page journal “Travels in the Slavonic Provinces of Turkey-in-Europe” (London 1866). Mackenzie later married Sir Charles Sebright, British consul in Corfu, where she died. Irby returned to the Balkans with her new friend, Priscilla Johnston, and the two of them set up a girls school in Sarajevo and were later involved in relief work.

Coming from Salonica and Skopje in 1861, Mackenzie and Irby visited Kaçanik, Graçanica, Prishtina, Vuçitërn, Peja, Deçan, Gjakova and Prizren, before venturing through the mountains of northern Albania to Shkodra. Their primary interests and sympathies were for the southern Slavs, especially for the Serbs, and they were not particularly sympathetic to the Albanian cause, yet they provide much information on the Albanians of Kosova and northern Albania. This extract is an account of their stay in Prizren.

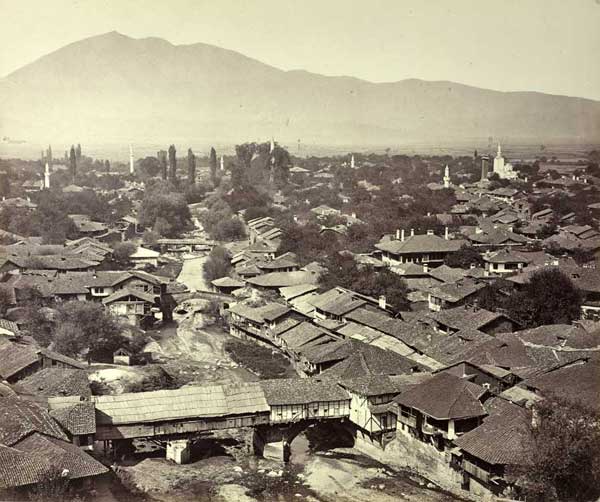

Prizren in September 1863

(Photo: Josef Székely,

ÖNB, VUES IV41070)The larger of our rooms in the Bishop’s palace was destined, as we were told, for receptions, and nowhere throughout our journey had we more need of such an apartment than at Prizren. Our visitors comprised Mussulmans, Roman Catholics, and Serbs. Among the first, came various deputies of the Pasha, to pay compliments and receive orders, also the poor old Mudir of Prishtina, already gone the way of Prishtinski mudirs. The Austrian agent and his wife we found both kind and civil to the utmost of their power; they were curious about old jewellery, and showed us some beautiful rings and antique gems bought up from impoverished Beys. Then there was the pro tem. master of the house, the Padre Vicario, an intelligent Italian of the Franciscan order, and various Albanian priests from the mountain parishes, who presented alike in dress and countenance, a strange compromise between the Miridite and the monk. An incongruous pair, representing each variety, drew the yoke of the ménage, the one a young Italian friar, the other an Albanian schoolmaster. One of our visitors was an old man, who brought a bottle of excellent red wine, and told us it was from a vineyard planted in Stephen Dushan’s time. He was so shabbily dressed that we thought of paying for the wine; thereupon found out that he was the richest merchant in the place. The most interesting members of the orthodox community waited to be summoned, and then came the mistress of the girls’ school, Pope Stephan, and Pope Kosta and his wife. Pope Kosta is a native of Vassoievitch, and besides being an energetic cicerone, is generally intelligent, and not wanting in tact.

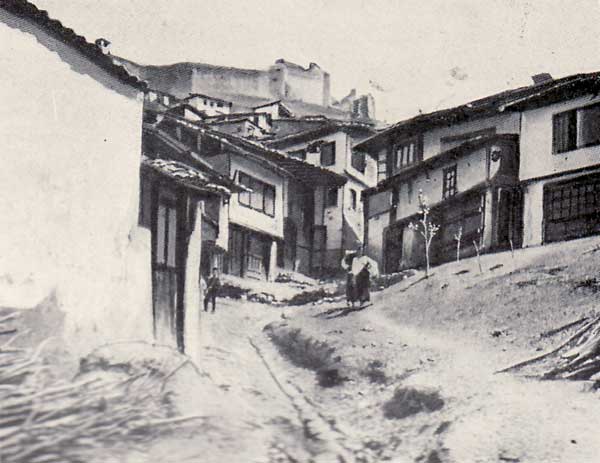

"Houses in Prizren"

(Photo: Gabriel Louis Jaray, 1913)

From the conversation and testimony of all these persons we extracted the following information respecting the present condition and inhabitants of the whilome Serbian czarigrad — In its streets are spoken Serbian, Albanian, Turkish; the presence of the latter language being accounted for as follows. On the first conquest of Prizren, its size, strength, and importance caused some genuine Ottoman families to settle there, while others were left in charge of the town; now-a-days the sons of the richer Prizren Mussulmans often go for their education to Stamboul; and for both these causes, Turkish, which is ignored in Ipek and Diakovo, forms one of the three languages of Prizren. That Serbian should still be considered the chief tongue, although the Christian inhabitants are in a minority, is due to the unalienably Serbian character and associations of the town; partly, also, it is said, because some of the Mahometans are of Serbian origin, — the majority are Arnaouts.

Prizren is the seat of a Pasha, but subordinate to a superior Pashalic, lately that of Scodra, now of Nish. From the presence of regular troops and the admixture of Ottoman families, the Arnaouts of Prizren comport themselves less unruly to the central government, less robber-like towards the Christians, than in Ipek and Diakovo. Still, they are a bad lot, their chief families going to poverty, and given up to vice and slothfulness; the most creditable members of the Moslem community would seem to be those craftsmen in steel who make the celebrated Prizren knives and scissors.

As to the chief town of the district, it is to Prizren that grave cases are referred for judgment; and throughout Stara Serbia we were constantly hearing of criminals sent thither “in chains.” It was, therefore, with additional regret that we heard from a source friendly to the Turks of the injustice and corruption of the Prizren administration. The terrible accounts of the state of the prison made us think of those dungeons celebrated in the old songs of Serbia, into which heroes sometimes fell when engaged on distant campaigns. These are described as filled with “water up to the shoulders, bones up to the knee, and in the water snakes and reptiles. In hope of ransom the captives are to be kept nine years, till the feet rot from their legs and the arms from their shoulders, till the serpents have sucked out their eyes: then turn them out into the street to beg their bread from the pity of the passers by.” If the prison of Prizren be not full of water and snakes, it is by all accounts full of filth and vermin; and if the prisoners are not kept nine years for ransom, they are certainly detained without judgment until they can bribe the authorities: innocent and guilty, healthy and fever-struck, huddled together for an unlimited time; moreover they must be provisioned by their relations, or they may expect to die of want. Not only for the sake of the Christian population between this and the Serbian frontier, but also to rouse and back the pasha in executing long-promised reforms, the presence of a sufficient number of energetic consuls is much desired at Prizren. At present, except the Austrian vice-consul, there is no European representative in the whole region of Old Serbia.

We saw a Bey of Prizren at home in the harem of the ex-mudir of Prishtina. Poor old man, he was scarcely recognisable ; and in spite of conventionalities as to the “will of Allah,” showed himself so put out by his deposition that we were glad to please him by agreeing to visit his dames. As an inducement, he proffered the acquaintance of his sister, who had been married to a pasha, and in her widowhood occupies a house next door to his own. She was, as he informed us, a properly educated and polished lady, and had been much in Stamboul. As the Stamboul ladies we had seen in the provinces usually wore a gown of European cotton or muslin, we assured him that we were especially anxious to see the Albanian ladies of his harem and should be much gratified by their wearing their national costume. Accordingly, the wife and daughter of the mudir received us in all the glory of white gauze and velvet over-robes, the latter magnificently worked and heavy with gold. Here, however, the ladies’ beauty began and ended; within the robes there appeared clumsy corpulence, above them painted faces and tawdry head-dress, and below, stockingless feet and toe-nails thickly bedaubed with henna. The Stamboul sister must have been very handsome ; her features, though wasted, were still refined. In virtue of her alliance with a Pasha, she played the grande dame of the harem; it was she who met us, led us in, and seated herself to entertain us, the fat wife and daughter brought the coffee, and afterwards stood fanning us. They made no attempt to join in the conversation, which flagged considerably, for we knew no Albanian, and these dames but little Slav. When we rose to depart, the mudir and his ladies invited us to take a walk in the garden “to see the water.” So the mudir led the way, and Madame Pasha accompanied us, gathering up her scanty gown, and thereby exposing bare feet and ankles. We passed through some long grass and a few small trees to a door in the wall; the door was opened, and behold a running stream. After this walk in the pleasure ground we took our leave.

In this and other harems we were amused to see attendants and mistresses watching our behaviour in order to detect some of those signs which in the East so precisely indicate who is to be considered the chief guest. The idea that people can be of equal position, and pay no attention to the minutiae of etiquette, is, in these countries, almost inconceivable; nor could our hostess be made to understand that we chose our places on the divan with regard to light and draught. For long we knew nothing of their observances, and with involuntary humility often seated ourselves in the lowest room, our only care being that inculcated alike by European and Christian rules of courtesy, viz., not to seize on that place which we supposed to be the best. Afterwards we sometimes amused ourselves with puzzling our hosts, nicely dividing between us all the infinitesimal marks of distinction; when they remarked this they did the same, now and then bestowing any indivisible attention on her whom they might think the oldest.

And now for the Roman Catholics. The Albanians of this persuasion are patronized and assisted with money from France, Austria, and Italy, and have colleges and schoolmasters provided from Rome; the only consular agent in Prizren is the Roman Catholic agent of Austria sent for their special protection, — hence we were a little surprised to hear from the Latins far more whining, begging, and lamentations than from the unbefriended Serbs. The fact is, that what with their Romanist allegiance drawing them off from the other native Christians, and what with their division into divers hostile tribes, precluding all settled aim and national consciousness; above all, from their habit of making Judas-bargains with the Turks, and expecting everything to be done for them by foreign Powers, — these people are demoralized as they never need have been by mere servitude, however hard. The best hope for their regeneration is that the French influence, which is now predominant, is used to promote union among all the Christians in the country. After the Roman Catholic Albanians found that we were inclined to applaud unity, they began to protest of their kindly feeling towards their Christian brethren; but when we first arrived, supposing that, as English, we should wish to believe the Christians of Turkey disunited among themselves, for the benefit of the Mahometan, they sang a very different song. Not that among these Latin communities there are not some good specimens; a foreign education gives many of their priests more polish than can be boasted by the Serb popes. Moreover their ecclesiastical authorities stand up bravely in their defence, and exert themselves for their interests in a way the Greek prelates seldom or never do. The late Roman Catholic bishop of Prizren is said to have been respected by men of all faiths, — a testimony confirmed even by the Russian Hilferding; it is due to his influence that the old cathedral was not utterly destroyed. It also speaks well for his taste that, even after the fine new episcopal residence was finished, he continued in his previous humble dwelling, and used the palace only for meetings. Doubtless he felt, what must strike every one at Prizren, that for the pastor to live in a style superior to all around him, while the community is poor, and the church wretchedly small, is an anomaly discreditable to any creed.

On the day of our arrival, the padre vicario was absent on a mission to Diakovo; on his return he told us its import, and begged us to join his supplications and efforts. In the first place, he was troubled about some Roman Catholic congregations in the mountains. During the heat of persecution they had pretended to be Mahometans; but when persecution decreased, and military service became a burden, they declared their Christianity and agreed to pay haratch. No sooner, however, was the haratch paid, than the Turks demanded military service also, ignored the return to Christianity, and required them to observe Mahometan customs as before. Secondly, the padre vicario was troubled about some Roman Catholic congregations in the plain. They had come down from the hills comparatively lately, and were colonists, i. e., tenants, not possessors of the soil. They used to prefer fighting for the Sultan to paying him tribute, and in the Crimean war lost many men. But the injustice they suffered, (1) and the embezzlement of their pay, had rendered them unwilling to render such service again; last year they would not march against Montenegro; hence the Turks were now demanding haratch. In both cases the padre complained against the Turks: “when they want haratch, they treat our people as Christians; when they want soldiers, they take them for Moslems.” Those who know the Turks will not think this statement improbable; but those who also know the Roman Catholic Albanians, may believe the Turks have some reason on their side when they assert that “these Latins are all Mussulmans to the tax-gatherer, and all Christians when called to war.” The colonists of the plain about Diakovo, knowing that their brethren in the mountains were able to defy the demand for haratch, had declared their resolution to return whence they came. “And why not?” said we; “for whose benefit do they stay where they now are? With the Turks they cannot agree; with the Christians they do not join; for themselves they prefer labouring in a less fertile soil to parting with the fruit of their labour in taxes ; and as for the land, so far as it is improved by any agriculture of theirs, they may as well scratch the earth in the mountain as in the plain.” “Nay, nay,” cried the padre; “you do not understand the question. If the Roman Catholics withdraw from these parts, we pastors shall be left without flocks”

The padre vicario told us that in sickness Mussulmans often asked for the prayers of the priests, apparently by way of a spell; and that the other day a hodgia came to him, and besought him to breathe on him and give him his blessing, as a means of curing some disease. The padre objected, representing that since the hodgia had no faith, the blessing would do him no good. “Never mind,” cried the hodgia, “only bless me; faith or no faith, it can do me no harm.” The priest laughed heartily at the hodgia’s stupidity; but it struck us as somewhat suspicious that he should have found fault only with lack of faith, instead of frankly stating that neither blessing nor breathing of his could avail to cure disease. It occurred to us from this anecdote that the Roman Catholic monks in Albania, like their Bosniac brethren, may profess to heal their congregations by means of all sorts of absurd practices, and possibly, like them, increase their slender incomes by writing talismans, of which the virtue is believed in by the ignorant Christians, and no less by the ignorant Turks.

The Roman Catholic priests we saw at Prizren gave us a good many interesting details respecting the chief of the most powerful tribe of Latin Albanians, commonly called the Prince of the Miridites. The title itself is a mistake, being really Prink, or Prenk (Peter), which is a common name in the chieftain’s family. The late Prenk held the rank of a general of brigade in the Turkish army, a circumstance which sufficiently marks the distinction between his position and that of his orthodox neighbour, the independent prince of Montenegro. We were anxious to hear how far this distinction was answered to by a difference in their respective modes of living, and in the condition of their subjects. Some persons have been prompt to assume that as regards the comfort, quiet, and civilisation of the highlanders of Montenegro, the only spoke in the wheel is the persistence of their prince not to recognise the nominal authority of the Sultan, thus compelling the Turks to treat them as foes. Like several other theories affecting the Montenegrines, this one should not be indulged without reference to the actual condition of the Latin Albanians who do acknowledge the Sultan’s authority, and even render him military service. From all that can be learnt on the subject, it seems certain that these Albanians are in a more barbarous condition than the wildest of the Montenegrines, and quite as impoverished and predatory; while they lack all signs of such modern improvement and organisation as that by which the last rulers of Montenegro have succeeded in establishing security and order within their own domains. Descriptions of Orosh, the residence of the Miridite chief, show it to be without even those features of the tiny capital of Montenegro, which indicate (to use the Prince of Serbia’s expression referring to his own dominions) “that at least the people have the intention to become civilised.” Such travellers as have made the acquaintance of the Princess and Princess-Dowager of Montenegro may judge of the difference between Montenegrine and Miridite manners, when they learn that it is customary for the Prenk not to marry a Christian woman, but to carry off a Mahometan and baptize her on purpose. During M. Hecquard’s visit to Orosh, the women’s apartments in the chief’s residence were tenanted by two widows, who had survived all their immediate male relatives, and having each killed a man in order that the number of dead might be equal on both sides, thereupon agreed to forgive the past, and live under one roof for the rest of their days.

At the time M. Hecquard’s work was published, the chief of the Miridites was by name Prenk Bib Doda. and his authority was not contested. More recently, a cousin has intrigued against him, and their quarrels have given occasion for interference both to the Porte and various Consuls. Further complications arose during the late Montenegrine war. The orthodox and Romanist mountaineers had for generations been enemies, and could be trusted to fight each other in the interest of their mutual foes; but the late Prince of Montenegro took pains to conciliate all Latin captives, and in the last war his policy was carried out. This made a great difference in the feelings of the Albanians, whose most potent motive power is revenge; they had also much to complain of against the Porte; and a priest, to whom we shall presently allude, preached strenuously that the Pope forbade them to take part with infidels against Christians. Thus it came to pass that some Miridites, together with other Albanians, marched against Montenegro, while some refused; and at the end of the war Prenk Bib Doda was summoned to Constantinople to explain. According to the version of the story current in his own country, he justified himself, was authorised to return home, flattered and honoured; but, just as he was going to start, he suddenly and suspiciously died. Meanwhile Turkey’s open foe, the Prince of Montenegro, remained safe and sound, independent, and at home. The contrast was not lost on his own subjects, nor on those of the Miridite Prenk. (2)

But to return to Prizren, where we have still to notice the orthodox (Pravo Slav) community. The archbishop was absent, and of him we heard contradictory opinions. Some said that he was on the mother’s side Bulgarian, and a friend to the Slavonic people and nation ; that he celebrated the liturgy in Slav, and protected deserving Serbians like Pope Kosta and Katerina of Ipek. Others said he was a Greek from Seres, where there is a large Bulgarian population; hence, knowing the Slavonic language, he was less distasteful to his flock, but nevertheless selfish, and addicted to Phanariote intrigue. He was even accused of being hostile to education, and of preventing the establishment of a higher Serbian school. Pope Kosta, as the archbishop’s secretary, came in for his share of blame. But whatever the archbishop may have done about a higher school, we can testify to the existence of two normal schools at Prizren. The boys’ school we visited, and found it a creditable structure, and provided with books from Belgrade. The girls’ school is in embryo, partly because many families are too poor to spare their children from home, partly from lack of communal funds sufficient to dispense instruction gratis, but chiefly because there is no competent teacher. The Prizren schoolmistress is a humble, good woman, in despair at her own ignorance, and really anxious to do her best. But Pope Kosta remarked, “We want a woman like Katerina. Her religious character gives her authority, she goes from house to house, finds out the children and takes them. Such a woman would fill our school.”

One obstacle to prosperity in the Serbian community of Prizren is that its most vigorous members draft off to the Principality. By their own account, no less than 500 families had lately emigrated; and though the Austrian Consul thought this number exaggerated, he allowed that as many and more would go but for the hindrance of the Turkish authorities. The associations of the old Czarigrad keep alive the spirit of freedom, and, unlike emigrants from more demoralised districts, the Prizrenites take kindly to European institutions, and having once walked with head erect, will never again stoop to the yoke. They offer their families all aid to follow them, but not even a refusal will induce them to return. More than one mother, bemoaning to us a son’s absence, imitated the gesture with which he forswore Mussulman dominion, shaking one side of the garment, and spitting violently on the ground. The few energetic men who remain are kept at home by the fears of timid relatives, and Pope Kosta pointed to his wife as the hindrance to his not holding a good position on the other side of the border. No sooner did the obstructive party suspect the approach of the contested subject, than she opened her batteries, crying, spreading out her hands, and conjuring him not to separate her from home and kin. The Serbian nation is obliged to such good matrons, for it certainly ought not to sever the last link between itself and the old lands; we have already noticed, that the government of the Principality does not encourage emigration from Old Serbia.

At parting we gave Pope Kosta our last Serbian Testament, little anticipating how welcome the gift would prove. He received the book without appearance of pleasure, and took it home with him the evening before we left Prizren. But next morning he re-appeared radiant, and accompanied by his wife and another relative. He said that he had begun reading to the women, and the language being such as they commonly use, the words came home to them familiarly as never in the Church-Slavonic version. They had sat up till late poring over the book, and now the pope was going forth into the villages to read it out to all the people.

During the Crimean war the Miridites served on the Danube, and distinguished themselves. “Là, pendant que le capitaine Biba était parti pour recruter de nouveaux soldats, le Général Omer Pacha, sans tenir compte des réclamations des Miridites, qui aux termes de leurs capitulations doivent être remplacés tous les six mois, incorpora dans le Nizam trois cents d’entre eux et renvoya les moins valides dans leurs foyers après les avoir désarmés.” Hecquard’s Haute Albanie, p. 243. Of the Roman Catholic populations in northern Albania, Lord Strangford remarks, that, after the Turkish, conquest, they were “able to maintain their religion and a certain amount of independence unmolested, and had no oppression to complain of. But the growth of their civilisation was checked; they were cut off from Europe, and buried from the sight of the world.” — Eastern Shores of the Adriatic. For M. Hecquard’s account of the Miridites, see Appendix. The same work gives some notices of the Albanian colonists on the Ipek plain. [excerpt from: G. Muir Mackenzie and A. P. Irby: The Slavonic Provinces of Turkey-in-Europe (London and New York: Alexander Strahan, 1866; reprinted New York: Arno Press, 1971), p. 467-479.]

TOP