| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1890

Victor Bérard:

Travels through Central Albania,

between Turkey and Contemporary Hellenism

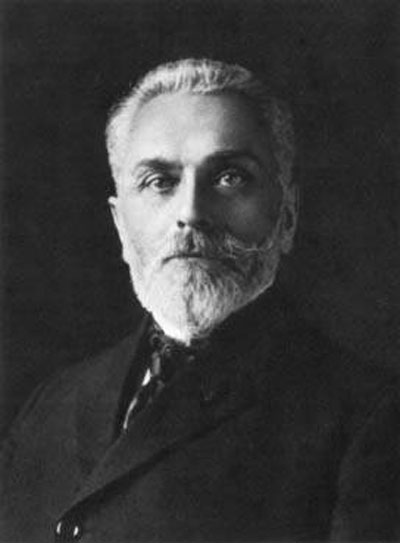

Victor Bérard (1864-1931)

Victor Bérard (1864-1931) was a French classicist and political figure from Morez in the Jura mountains. He studied at the Ecole normale supérieure in Paris, specialized in Homeric studies and travelled much in Greece and the Ottoman Empire. He was a member of the French School of Athens, translated the Odyssey into French, and taught historical geography for many years (1908-1931) at the Ecole pratique des hautes études in Paris. In later years, Bérard was a senator for the Jura region (1920-1931) and was head of the Senate’s foreign affairs committee. He was the author of several books, primarily concerning the Odyssey, Greece and Turkey. In August 1890, he and his friend Emile Legrand (1841-1903), author of “Bibliographie Albanaise” [Albanian Bibliography], Athens 1912, travelled through Albania on their way to Macedonia. The following excerpts from this journey from Durrës through Kavaja, Peqin and Elbasan are taken from his first book, “La Turquie et l’hellénisme contemporain” [Turkey and Contemporary Hellenism], Paris 1893.

The salvoes and bells that resounded for the fifteenth of August had difficulty waking our crew who had spent the whole night celebrating the feast of the Madonna. Our Austrian Lloyd steamer, the Iris, sailed slowly out of the Bay of Kotor [Cattaro] as befitting for the feast of the Assumption. The ship passed numerous headlands of this jagged coastline and stopped for several hours to rest in sunlit azure coves, before resuming its lazy advance from Kotor to Budva and from Budva to Lastva. All day long, on Austrian soil and on small boats decked out in flags, bands in their finest clothes saluted us with their festive songs, and little soldiers fired cannons for the Madonna. It was only in the evening that silence and solitude gained the upper hand as we reached the Orthodox coastline of Montenegro. We had entered the Orient.

In a bay surrounded by mountains and protected by a high cliff were rows of white houses, all with red tiled roofs and green shutters that gave the impression of a model village built on orders. All the houses, all the windows and all the gates were alike. This was Ulqin/Ulcinj [Dulcigno], a Montenegrin town arising out of Turkish ruins, putting behind it its old fortress and decrepit mosque at the end of the promontory.

In the distant flatland, obscured by the smoke of burning leaves, was a steamy river full of rushes meandering down towards the sea. This was the Buna [Boyana]. After another headland and a semicircular bay, we could see the first Turkish flag flying over a solitary guard post – Shëngjin [Saint John of Medua], the port for Shkodra. Exhausted from his short journey, the Iris spent the night recuperating in the muddy and putrid waters that the Drin and Buna Rivers poured into this gulf.

In the morning, we sailed on down the Albanian coast. The transparent depths of the Dalmatian sea and the cliffs of Montenegro faded behind us. The low, hazy coastline seemed to dissolve into the mud and floating foam. The large alluvial plain stretched from the sea to the distant mountains along the hundred kilometres of coastline stretching from north to south. The only thing that interrupted the monotony were a few rocky headlands vaguely attached to the mainland by marshy isthmuses. The mountains, perpendicular to the coast, grew higher and higher as we progressed southwards to the impassable barrier of Acroceraunia, that constitutes the end of the Adriatic Sea.

The wharf of the customs office in Durrës (coloured postcard, 1914).The first cape, Rodoni, was nothing more than the short summit of a protruding hill. Next was Cape Pali that was seven kilometres in length and rose, almost like a mountain, to about 200 metres in elevation. Two sandbanks around a lagoon served as moorings.

Exiguo debet, quod non est insula, colli

proclaimed a quiet and bespectacled German traveller on his way to Athens, with a volume of Lucan in his pocket, and greeted ancient Dyrrachium with this line. And so it was. Among the trees and ruins behind the rocky headland, a church, two minarets, crenellated walls and a Turkish flag announced Durrës [Durazzo] to our south,

Arrival in Durrës

Our German was surprised to see two Europeans, two almost educated Frenchmen, get off the steamer here with the intent of journeying to the distant barbarian land of Macedonia instead of making their way to Corfu and divine Hellas. “And in search of Bulgarians, Albanians and Serbs! Macedonia was the kingdom of Alexander. There is nothing else of interest there.” For Europe, Macedonia was indeed a vague country, a kingdom lost somewhere between the Danube and Salonica, a country of mountains and forests where Alexander the Great once held sway. We, who were getting off the ship, knew little more about it and would be free to make our judgement when we got there.

The walls of Durrës (coloured postcard, 1914).We only hoped that on the beach, on time, we would find our two Albanians and four horses. The Albanians were old friends of ours. One of them, Abeddin, a Muslim, was a zaptieh (gendarme) of His Highness. The other one, Kostas, a Christian and one-time shepherd, was the former kavass of the consulate. He was more Greek than Albanian. He boasted that he had spent several months of his youth as a bandit, and this was why we hired him. To travel in Turkey, it is a good idea to have a policeman to one’s right and a bandit to one’s left. Both of them can prove useful when the moment comes.

The two of them had accompanied us through Epirus and southern Albania. Two weeks ago, when we boarded the steamer from Vlora to Shkodra, we sent them overland with the animals and our luggage. We showed them the route on the map. “Efendi, do not worry,” said Abeddin. “We will cross the rivers and reach that town. And we will go and sit on the beach and wait for you to come.”

Keeping far from the coast because of the sandbars and reefs, the Iris sailed around the peninsula and entered the narrow channel of the port near the mainland. This port, where Pompey’s fleet once manoeuvred, where Robert Guiscard landed, and which was fought over for a century by the Angevins of Naples and the Comnenas of Byzantium, this poor port was nothing more than a shallow marshland. A few Dalmatian sailboats, two Turkish caiques and an Italian steamer were enough to fill it up.

The fezzes of our two Albanians shone out like two crimson dots on the shore. Kostas was dressed in his white fustanella and his well-washed stockings. Abeddin was even more impressive in his blue uniform and its orange-coloured braiding. They kissed our hands when we met them. They had been waiting there for eight days! Every morning, as they promised, they went down to the shore and sat by the sea until sunset when they returned to the inn to attend to the horses. Their trip had proved a great adventure. They took ferries across some of the great rivers, swam across others or waded through them in the mud. For the last seven days they had been swimming, dressing their animals, repairing their saddles and polishing their weapons. They had begun to lose all hope as Durrës, with all the mosquitos and fever, was a difficult place to stay in. The horses refused to drink the well water and a mutessarif (Turkish prefect) had endeavoured to requisition our animals and men for a fight against bandits in the interior. What people these men of Durrës were! Neither Christians nor Turks. Almost all of them were papists and “macaronadis” (this is the term our Albanians used for the Italians). We had to get away, concluded our civil and military entourage.

Above the landing were crenelated walls. The one sole port, the quay called Porta Yali, led into the town past the customs office and the police. Our passports were examined thoroughly and the tips we gave (as our passports were not in order) proved sufficient. We were given leave to enter.

Durrës is a strange mixture of Turkish buildings and Italian shops amidst Frankish and Byzantine battlements. It seemed as if the Turks had arrived in this Venetian town yesterday. Up near the domed mosque, the mutessarif had built himself a huge palace, an earthen and wooden konak. The stairwells and halls were buzzing with supplicants, high-turbaned imams, veiled women and ragged policemen. Soldiers were cooking or making coffee in the courtyard. Prisoners stretched their heavily chained arms through wooden bars, begging for cigarettes. Orthodox priests were arguing in Greek. Artillerymen were moving around an old bronze cannon. Everyone was at home here. This is what I imagined a prefecture must be like in a country of paternal tyranny.

In the twisty, narrow flagstone alleys of the lower town, there were Italian signs and Italian products in all the shops. Pottery from Calabria, noodles, earthenware, liquor from Milan, Chianti wines. Children were coming out of the Italian school, singing Neapolitan songs such as one might hear from Genova to Brindisi, the eternal barcarolles in which fair maidens leave for bella Venezia. The consul of King Umberto had placed huge escutcheons at the doorway, on the balcony and in the window of his school.

The old walls enclosed the town in a narrow embrace. Reduced to a rectangle of 600 to 300 metres at the most, Durrës was but a village twenty years ago. The Turkish prefect did not even live here. He resided in the countryside at Kavaja on the other side of the gulf. Italian boats and Italian plots have revived this dead town. Boats arrive from Brindisi twice a week, and the plots are a secret to no one. People in the streets can tell you who is receiving money. The monthly amount varies from between four and six Turkish pounds (92 and 138 francs).

The Christian Albanians in the lower town willingly use Italian currency, as do even Turkish officials and some Muslim beys. The Christians from the Gheg tribes (northern Albanians) have remained Catholic. Since the days of Venice and the kings of Naples, Jesuit missionaries in Tirana and Shkodra and local bishops educated at seminaries in Rome and Padua have helped to preserve Italian traditions, and the Italian language is well at home here. Every month, the Italian consul in Shkodra pays out almost two hundred Napoleons. But the Catholic Ghegs have refused to be drawn in entirely by the enemies of the Papacy. Italian propaganda will remain ineffective for as long as the Vatican and the Quirinal are at war with one another, and even more ineffective for as long as Italy remains an enemy of France. The Mirdita, the noblest Gheg clan, with the princely family of Bib Doda, have always considered themselves as being under French protection.

The Greeks seem to have lost out here. The Adriatic never had any appeal for their sailors. Even their ancestors regarded Epidamnos, that later became Durrës, as distant Epidamnos. This perfidious promontory provides little shelter from the wind and the Adriatic Sea is subject to many storms. The Greeks miss their serene bays and clement seas here, and the Greek flag is rarely seen beyond the straits of Otranto. Nonetheless, Hellenism retains a claims upon Corinthian Dyrrachium. There is a Greek school but it is outside the town, in a suburb called Exo Bazari (Outer Market).

As its name suggests, this suburb is a fairground of moveable stalls, flying tarpaulin and temporary huts that fills up in the morning with caravans from the interior. It is here that Catholic Albanians from Tirana meet Orthodox and Muslim Albanians from Kavaja, that beys from Elbasan and Berat meet Kutzovlachs from the Pindus Mountains and from Korça.

Hellenism recruits its partisans from among the Orthodox Albanians and the Kutzovlachs. The town itself may be Italian, but the suburb is Greek. Greek is spoken in all the cafés here and the walls of shops are plastered in portraits of King George I and his minister, Mr Tricoupis. Under the plane trees, groups of drinkers in fustanellas sing melancholic Aegean songs with their guitars.

It was in Exo Bazari, far from the “macaronadis,” that our Albanians found lodgings for us worthy men in a han (inn) that was less comfortable than the Italian inns but more Christian, i.e. Orthodox. For the Greeks, christianos always means Greek Orthodox. Aside from the Greek school, this han was the only permanent building in this suburb. Its earthen and wooden walls looked temporary by European standards, but here… The water, the mosquitos and the fever of Durrës conformed to the description our Albanians had made of it. It would be difficult to imagine an unhealthier place. Two-thirds of the 3,000 inhabitants of the town abandon it in July and many of the shops were still empty.

How strong traditions still are in Turkey! A Kutzovlach caravan arrived from Monastir [Bitola] after a seven-day journey. These Kutzovlachs (lame Vlachs) are a people of Latin origin that Pouqueville, towards the end of the last century, placed as coming from the two slopes of the Pindus Mountains, between Larissa and Janina. All business in southern Albania was in their hands at that time. From Voskopoja [Moschopolis] near Korça, Syrrakou, Kalarrytais, Mezzovo and Larissa, centres of the Anovlachs, they spread throughout the country, selling the products of their labour – hides, leather, silverwork, capes, felt hats and carpets, or the merchandise they received from their branch offices in Leghorn, Vienna and Amsterdam. Durrës was their natural port for contacts with Ancona, Dubrovnik [Ragusa] and Venice. Following the Greek Revolution, the Vlachs, who called themselves Greeks and who had fought for freedom with their money and blood, emigrated in great numbers to the new Kingdom of Greece and were scattered. The towns of the Pindus range thus lost their role and importance. The merchants of Voskopoja settled elsewhere, in the large Muslim cities of Salonica and Monastir. Nonetheless, a century later, although there is no more reason for it, Durrës remains a Kutzovlach port. Caravans from Monastir arrive here every Saturday.

In Exo Bazari, great discussions arose from the news brought from Europe on the Austrian steamer. Newspapers and public gossip made it known that the Sultan intended to give the Macedonian dioceses of Veles, Skopje [Uskub] and Ohrid [Okhrida] to Bulgarian bishops. The documents of investiture (berats) had already been signed. This news left no one indifferent. The Muslims would not admit that the Sultan had made such a concession to the “thieves of Roumelia.” They hated the Bulgarians more than they did “Moscoff.” The Christians smiled in disbelief. “It is unimaginable that the Bulgarian Orthodox should get the upper hand over the Patriarch. Moreover, the Macedonians are Greeks and not Bulgarians. They want Greek clergy and Greek schools.” In a little café, the school teacher, standing under portraits of George I and Tricoupis, invoked Aristotle, Philip and Alexander.

Abeddin and Kostas, servants of our illustrious persons, were surrounded and consulted. They let it be known that the Sultan had not decided anything yet since we were now only leaving for Macedonia. If the berats were granted, we would be the first to know. “Are they Christians?” asked the teacher. “No,” replied Kostas, “they are Catholics, but they do not particularly care for the Bulgarians.”

Durrës is connected to the mainland by a thin belt of sand, but even the narrow roadway that runs between the sea and the brackish lagoon is cut off by a stream flowing into the lagoon. The wooden bridge that was built over it recently is already on the verge of collapse. […]

After three kilometres, the road turns into a track in the sand, about one metre wide through the swampy parts and two hundred metres wide over the easy sections. We advanced around the bay of Durrës. Not a village in sight, not even a cottage. The country was deserted. Every once and a while, under a shelter of reeds, a couple of Turkish gendarmes watched over the security of passers-by. These ones ran a little café where they sold water and melons that other passers-by had given them, freely I hoped. At any rate, the gendarmes did not ask us for anything. They were happy with the alms we gave them.

Kavaja

From a hillside, we caught sight of Kavaja, radiant with gardens and trees. From the distance we could tell from its location, aspect and colour that it was a Muslim town. The Giaours founded Durrës, but the faithful settled in Kavaja. Islam avoids the sea that is dear to the Giaours. On the coast where the water is never good and security is never perfect, they prefer verdant lands at the foot of hills where springs flow for their ritual ablutions and where large trees offer shade for long siestas and quiet conversations.

The Mosque of Kavaja (photo: Richard Busch-Zantner 1939).We passed by lines of small donkeys loaded with mats and jugs. Large, devilish Albanians kept them plodding along with their shouts and knives. Over their shoulders they were carrying rifles of various types and long gravestones of roughly hewn marble that they plant at the heads and feet of their dead. We happened to arrive at Kavaja market on gravestone day. Everyone was stalking up to cover their annual needs, as explained to us with a smile by Osman Aga whom we happened to meet. His donkey was carrying three fine gravestones embellished with turbans and green and yellow writing. After all, he had an aged father, a sick child and was himself involved in a number of murders. In a country of never-ending feuds, Osman Aga was obliged to think about his future. […]

Albanian was the language here, an Albanian quite different from the dialects of the south. Kostas and Abeddin were surprised. “The people here speak through their throats like the Turks, and not through their noses like the Greeks.”

This district was Muslim and looked indeed like a land of the Prophet. Stones along the roadside, fountains with copper taps, and little grass lawns in the shade of plane trees. It was here that passers-by bowed to say their prayers. There were veiled women in red bloomers and five or six negroes come from who knows where, but which every Muslim town seemed to have. The Muslims are indifferent to their colour and treat them as brothers. And then there were the storks treading fearlessly and gravely over Muslim fields. Of the 16,000 inhabitants of this kaza (sub-prefecture), only 2,000 were Christian.

But be they Christians or Muslims, they are all Albanian by nationality. The Asian Turks never settled in this region. They made but a brief appearance here during the conquest and the natives conserved their Christian religion for a long time. It was only at the end of the last century and at the beginning of ours, at the time of Ali of Tepelena, that, nolens volens, a mass conversion took place. The new converts are, however, no fanatics. The Muslims of Kavaja all attend their mosque, a beautiful, spacious building with a dome, surrounded by porticos. The marble façades rise under the cypress trees, with Byzantine columns and Arabic ogives, but the open vaults are in need of repair by some pious benefactor. Just like their mosque, the religion of these Albanians is simply a façade. They have a monastery of very holy dervishes where they carouse every Friday with dancing, shouting and lots of drink. They achieve a less religious state of intoxication every day with raki and German liquor. They forget none of their ablutions and ritual purifications, but our tinned pork did not cause any noticeable repugnance. They simply renamed it “mutton from Algeria.” Aside from the imams and the men at the mosque wearing turbans, long robes and fur caftans, they all wear their national costumes. Some of them are in southern fustanellas, stockings and braided vests. Others from the north wear black caps and headpieces, vests and long white trousers embroidered with black braiding in arabesques. All of them seem to be called Osman son of Vasil, or Mehmet son of George, thus evincing a Muslim first name with a Christian father or ancestor.

To ensure equal treatment or favours from the prefect, the Christians, for their part, are willing to show a certain respect for Mecca. They observe the fasting period and Ramadan, they baptise and circumcise their sons, and they do their best to practise the religion of Mohammed in public while practising that of Jesus Christ at home. No one is upset by this ambivalence.

They are united in their politics and are quite content as long as the government does not intervene in their family quarrels. They scrape along with the produce they grow and with their flocks, and they seem to live exclusively on maize and dairy products. Their women dress in cotton fabrics and their children run around naked.

It must also be noted that these Albanians, both the Christians and the Muslims, are very devoted to Sultan Abdul Hamid II. We heard nothing but praise for the Padishah from people who were certainly no sycophants: he is a saint, he loves his people, and he protects Albania.

This last phrase has its reasons. The Albanians now get all the favours. They enjoy unrestricted liberty (they can indulge in their vendettas without interference from the indifferent Turks) and they enjoy positions, honours and high office as much as they want. It is of Albanians that the Sultan has composed his guard and his corps of officials. Constantinople and Asia Minor are governed by Albanian officials – prefects, judges, customs officers and zaptiehs. I have come across them even in Karaman.

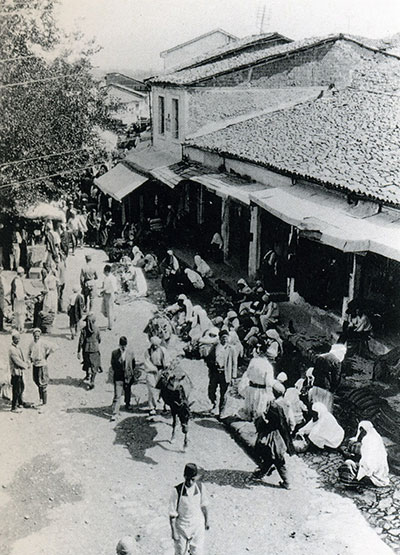

The bazaar of Kavaja (Italian postcard, 1930s?).The Turks have a two-fold advantage from this policy. With the old feudal system being conserved in this country, an aristocracy of pashas and beys owns the land and can do what it wants with the tenants on it. By heaping the beys with honours far from their country, i.e. by appointing them, whether they want it or not, as governors of Bursa or Konya, as mutessarifs of Kütahja (Vesel Pasha), Diyarbakir (Isuf Bey) or Chios (Kemal Bey), as ambassadors in Belgrade (Feridun Bey) and Madrid (Turkan Bey), the Porte is assured both of their absence from the country where dreams of grandeur and memories of Ali of Tepelena could trouble their loyalty, and at the same time it is assured of their presence in positions for which their exceptionally keen intelligence, their swift adaptability to all situations, and their supple brutality have always been of great service. In such a situation, Italian intrigues have little success. They have only managed to compromise a few wretches guilty of negligence or sloth, a few beys or agas forced to sell because they were being pursued by their creditors.

In general, the people of Kavaja have little interest in what is going on on the other side of the Adriatic. In earlier times, they delighted in travelling across the sea to serve in the Albanian guards of the kings of Naples or in seeking their fortune on the highways of Calabria. These were the good old days of highway robbery and mercenary troops. Nowadays, Italy has become almost European, and gallant fighters are no longer held in high esteem. The Piedmontese have monopolised everything, and any activity on the highways is swiftly put down. Bad times for Albanians.

As to Hellenism, it is a term that is rarely heard and not understood here, even under the vine arbours, boarding and old sack cloth that protect the alleys of the bazaar from the sun. With the exception of two innkeepers from Corfu, Ithaka or Patras, the bazaar is entirely Muslim. Here one finds earthenware pots, mats, flintlocks, copper and silver pistols, gravestones, sweets dripping with honey, a few European textiles and more and more rifles and guns, as well as heaps of red, purple, blue and green candies that are crude for both the eye and the taste buds, but in which the Muslim population takes great delight during Ramadan.

The inn of Kavaja was full of zaptiehs (gendarmes). The vaulted entrance and the courtyard were brimming with horses. In the stairwells, on the wooden balconies and even on the hard-earth terraces there was a confusion of bodies, weapons, harnesses and military cots with neither mattresses nor springs. It was the ground or wooden boards that served as mattresses and the saddles that were used as bolsters. […]

Peqin – an Albanian Fief

For us to be able to pass through this “bandit country,” the Yüzbashi doubled our military support. We already had the zaptieh Abeddin, and we were now given a nizam (foot soldier of the regular army) called Mehmet, riding on a borrowed mule. The Binbashi would indeed have tripled our protection. His superior spoke of twelve or fifteen zaptiehs that we could have. They knew that we would tip the men and that some of the money would get back to them. Twelve gendarmes would thus be very useful to them, and perhaps to us, too.

The Mosque of Peqin (photo: Shan Pici, 1925).At dawn, we left Kavaja asleep. The alleys of the closed bazaar revealed all their misery with badly boarded stalls and tattered canopies. Stray dogs were stretched out on piles of straw and dung, covered in the morning dew. Storks languished on gables. In front of the dervish house, there was a white chest almost at ground level that was full of arms. Double-headed axes and instruments of torture painted in red and green hung from the walls, as the muezzin waited for the first rays of dawn. […]

After four hours of travel over the plains and in the dust, we reached the Shkumbin [Skumbi] River and the village of Peqin [Pekini]. The Shkumbin, like all the other rivers on this plain, is too deep in its bed to be seen from a distance. But soon there appeared fields of maize and clumps of trees here and there. The track used by man and beast subsided more and more every day. Finally, there were thorn bush fences and cobblestone pavement that announced our approach to the village.

This cobblestone is, alas, to be found at the entrance to all Turkish villages. No one dares to use it. Neither men on foot or on horseback, nor women going to the fountain, nor buffaloes plodding homeward from their ploughing will walk on it. Everyone, locals and foreigners, even the goats, avoid these narrow roads of slippery and awkwardly set stones. If one wants to avoid breaking one’s neck, it is advisable to use the paths at the side of the road. Why such a cobblestone nightmare, worthy of the Seljuks, in all the towns and villages from Aleppo to Shkodra? Let us be modest. Turkish roads were the envy of Europe in the seventeenth century. Lady Montague had not seen such engineering marvels in England, France or Germany.

Peqin was a simple bazaar, a road bordered by temporary, ever temporary stalls that came to life once a week when peasants from the surroundings gathered to go to market. Today, the village was asleep. Vendors crouched in the doorways of their shops in the shade of their canopies. Dogs and naked children played in the brazing sun. Here we encounter edAlbanians, some Christian Vlachs, a Greek from Vlora who spoke Italian and French, and, for the first time, Turks. […]

The large domed mosque here, similar to the one in Kavaja with the same portico, was in a similar state of ruin. The square tower of its minaret with a clock on it looked rather like a Christian bell tower. The kaza of Peqin, entirely Muslim, consists of about 3,000 inhabitants, of whom less than two hundred are Christian Vlachs. Aside from the sixty to eighty Ottoman families, these Muslims are very tolerant in their faith.

Near the bazaar in which cloth and European textiles are displayed, as are sacks of vegetables, horseshoes and some hardware, there are about fifty earthen huts under the cypress and walnut trees around the residence, or should one say, fortress of Demir Bey. The ditches and earthen slopes of the fortress have been destroyed pursuant to a recent order from Constantinople. But the high surrounding walls made of good stonework are still standing. They form a square about one hundred metres in length, fortified in each corner by a ten-sided bastion. The cannons are missing from the gaping loopholes.

We were not given leave to enter as the bey had departed for one of his farms, but from the top of the walls covered in clematis and ivy, under old plane trees and poplars, we could see his wooden palace, its kiosks with raised roofs, pavilions and sheds. The corridors, balconies and windows evinced broken railings and rotten shutters. The outer walls were once covered in frescos. We could also see wood-paneled interiors with long couches around the sides of the rooms. The decorations were simple and the colours were even more basic. In pale hues of yellow, blue, green and red, the artist had endeavoured to depict the Albanian environment – horses, cypress trees, minarets, rifles, sabres, roses, warriors cutting heads off, bodies from which rivers of blood was gushing, Constantinople, Mecca, boats on the sea, and red cannons firing green cannonballs. The artwork had faded and virtually vanished. The rain diluted it and the exposed wood turned black. From the branches and black planks, a flock of crows rose with a cry. Only one corner of the central building looked inhabitable.

Demir Bey was, however, one of the great landowners of Albania. All the villages of this region belonged to him. His revenue probably exceeded 2,000 Turkish pounds (46,000 francs) and, according to Malik Pasha of Libohova and Fezul Aga of Delvina, his father-in-law, Omer Bey, the head of the Vrioni family in Berat, was the richest man in Albania. But Demir Bey’s income came to him in kind. At harvest time, the peasants give him one-third or half of the harvest – a third when the peasant is paying his tithes and taxes to the government, and half when the tax goes directly to the bey. This is normal practice in all of Albania. The standard crop that is harvested more or less throughout the country is maize. It is consumed by the Albanians and they grow nothing else. In his fortress, Demir Bey also had large wooden sheds. Between the planks caving in from the pressure hung ears of maize grown mouldy in the rain. The harvest of the last three years was rotting here without Demir Bey able or willing to sell it. […]

No European nation has yet discovered this grain market. The Austrian Lloyd that stops in Durrës exports none of it. The Greek ships that used to load grain for Corfu and Patras no longer sail in these waters. And the French companies, Fraissinet, Paquet and others, never show their flag in the Adriatic. Commerce has habits of its own. The merchants of Marseille still think there is nothing of interest to them in this Venetian lake.

But the real cause of ruin for Demir Bey is politics. Demir Bey has intimate problems in the Divan, problems with Albanians of rival families in hereditary vendettas that have been going on for centuries – robbery, rape, denunciations, fires and sabre wounds. Demir has made his situation worse by refusing to take a post as a governor general (vali) in Asia Minor. The Porte, wary of his influence, proposed this disguised exile for him, but Demir, who is stubborn and in ill health, refused. As such, a few days after his marriage, he and his father-in-law were accused of usurping public and religious land. The mosques of Constantinople and the Sultan’s mother possess large stretches of vakufs (religious endowments) in this region. The farms of Demir Bey will probably enrich them all the more unless he agrees to be made pasha of Konya or Sivas or unless he accepts some honorary, though badly paid function at an embassy far away from here.

The kaymakam (sub-prefect) of Peqin refused to inspect our passports and did not recognise our gendarmes, saying that anyone could have a passport, a uniform or the weapons of a zaptieh. He said he would have to contact Berat in writing. There was a telegraph office, but the kaymakam did not have a telegraphist available.

We replied to the sub-prefect that, being used to the ways of the world and of Turkey, we always carried clinking arguments in our purses, but that being French and friends of Dervish Pasha, we had too much respect for the Sultan to buy off his officials. The sub-prefect protested that he had taken us for Greeks.

Dervish Pasha, the former vali of Shkodra during the show of force in Ulqin [Dulcigno], is the supreme authority here. Having the confidence of the Sultan, he is a great minister of Albanian affairs. He distributes positions and carries weight in court houses and government. He is always on the lookout for affairs to his advantage. “He is a devil” or “he is a horned dog,” say the Christians in loud disgust, and the Pasha of L. swore only by this “sly fox.”

The sub-prefect, who had now become our friend, begged us to inform Dervish Pasha about all the progress that had been made in the kaza of Peqin: the roads that had been maintained and well paved; the Muslim school that had been opened (in the portico of the mosque) with twelve little children reciting the Koran around an old imam with glasses and a cane; and most of all that brigandage had been done away with. What a shame that we had not been there during last Bayram. What a splendid gendarmerie the kaymakam would have shown is. Thieves cannot do what they want here, as they can in Janina or Shkodra!

Yet the kaymakam urged us not to spend the night in town, where we would not be secure because his gendarmes were all with Demir Bey. Indeed he even encouraged us to leave, in the midday heat, and to travel in the afternoon. As he was responsible for the respectable gentlemen that we were, he begged us not to stop under any circumstances before we reached Elbasan, a large town where we would find many hans and zaptiehs.

The empty fortress of Peqin (photo: Robert Elsie, November 2010).Leaving Peqin, we had a few hundred metres of cobblestone to get past, along dry earthen walls under walnut, plane and cypress trees. In the dark and humid shade, we passed Muslim cemeteries among the ferns, with standing and toppled gravestones. Silence reigned here. Suddenly we emerged once again into the glaring sun of the barren plain. The track, that had led us in a northwest to southeast direction since Durrës, now turned and led us directly eastwards. In front of us, on the distant horizon, the plain began to narrow between high mountains. Without realizing it, we reached the bed of the Shkumbin, with its wide, precipitous and muddy banks. The water was brown with alluvial soil. Its languishing, muddy flow continued the mighty work of erosion, transforming an ancient lake into land today. […]

The heat and monotony of the plain continued to be unbearable. At the Muslim village of Kerno we reached the foot of the first hills. We had already been travelling for eight hours from Kavaja. Our horses appreciated the rest, as we did, too. But it was impossible to stop here for the night. […]

Elbasan

The day terminated in a long dusk marred by rain and storm clouds when, having left the river bed, we reached the plain of Elbasan. High wooded mountains surrounded the barren plain and a twisty line of willows and poplars marked the course of the river. Groves of trees and greenery indicated the sites of villages. Across from us, at the other end, rose the minarets of Elbasan among the cypress trees.

The bazaar of Elbasan (photo: G. Braca, 1927).

This final trek across the wet and muddy plain interrupted by streams without bridges, ponds and rivulets in the twilight exhausted our horses. Everything was grey – the water, the sky and the soil. The beasts slipped and slid in the clay that shone like white silk. Night fell and there was no more track to be seen. Then came the cobblestone, that eternal cobblestone, to exhaust our brave beasts all the more. Earthen walls rose on both sides and we could see a group of women in red tatters fetching water at a well with their lanterns. Two cypress trees loomed in the dark. Near a domed mosque was a lamp burning at the gate, hung with rags, of the tomb of some saint. Under the trees was a cemetery and then the streets of the bazaar. The shops were closed and the streets were unlit. A pack of dogs was fighting over a dead ewe. Finally we reached the great gate, the galleries and wooden stairs of the han. In the courtyard, near a fire in which a lamb was being roasted, zaptiehs were beating a group of prisoners with the butts of their rifles.

We had to stop in Elbasan. Our animals and our men needed a rest. The rain had made the trail unusable and, in addition, the route to Monastir was blocked, it was said, by an uprising of the mountain men of Dibra. But there was enough to see in Elbasan for two or three days.

The location of the town is sufficient to explain its existence. Situated on the right bank of the Shkumbin River, it separates the upper valley from the river, as Berat does with the Lumi and Tepelena does with the Vjosa [Voioussa]. But Elbasan is better suited than the other two towns to becoming a great centre because the course of its river has always been and remains the major road of access to Macedonia, the ancient Roman road from the Adriatic to the Aegean. In addition, it is here that the road from Macedonia crosses another major route stretching north-south, from Shkodra to Janina via Kruja [Kroia], Berat and Përmet [Premeti]. Finally, being 150 metres above sea level, with mixed forests, abundant water and rich alluvial soil, and with a mild climate, this plain would seem perfectly designed to nourish a large population.

The entrance to the fortress of Elbasan (photo: 1920s).

The town and its current inhabitants are divided into three neighbourhoods: three peoples who live side by side in three concentric rings. At the centre within the walls of the ancient fortress, i.e. in the castle (castro), were Albanian Christians – 150 to 200 families, being 750 to 800 individuals. Around the fortress there was a ring of Albanian Muslims – 500 to 600 houses, being 2,000 to 3,000 individuals. And outside this ring was another ring of 160 to 180 houses of Vlachs (i.e. about 800 additional Christians). In Berat, we had come across a Christian population within the fortress on the mountain top whereas the Muslim population lived on the plain below. […]

The fortress of Elbasan is surrounded by fair walls dating from the Roman and Byzantine periods, in brick and stone. Razed and ruined after the revolt of 1830, they now served as quarries. The Turkish authorities used them for the construction of government buildings, for paving roads and for private mansions. […]

Mothers and widows veiled in white and wrapped in black feredjes from their necks to their yellow boots had come to visit the dead and tell them the latest news from Elbasan. An old woman was weeping, slumped beside the head of her grandson. Her daughters and daughters-in-law stood all around her. With her withered hands on the flagstone, she endeavoured to revive her memories of the dead. There she sat for quite some time without saying a thing, fingering the stone and weeping. Then she began her lamentation: “Why have you left us, oh my carnation? Come back. Come and sit at our table. We weep black tears and you do not return. Come back, my eyes, my heart.” Her fingers went back and forth across the stone. We had stopped near to her and she called me to come over and sit beside her. “He was as tall as you are, and was of your age.” Had I no mother or sisters that I was travelling so far from home? From the table, she took two fish, a piece of bread and a handful of flowers that she gave me so that I would not encounter any misfortune on my journey, so that the evil spirits would spare me in the night and so that my mother would see me once again.

She then led us over to the men who were flapping their fustanellas amongst the weepers, discussing the affairs of the world and staring at us malevolently. But with our first words of Greek, they became more hospitable.

At the home of one of the heads of their community, one of the stewards, amongst all the men in fustanellas, we met two Europeans, two students from the University of Athens. We were treated to sweets, liquor and cigarettes. As soon as they found out that we were French, they hastened over to the wall and took down the portrait of Alexander of Battenburg who had been hanging in front of Gambetta. The room was adorned with the heads of the sovereigns of Europe in coloured lithographs. German Wilhelms and Bismarcks, Austrian Elisabeths, a Carnot, a Boulanger and ten or twenty Russian pictures by persons unknown but distributed en masse free of change from the Danube to Cape Matapan and from Jerusalem to Kotor. […]

The Christian community in Elbasan is a lost beacon of Hellenism in the north. All the Albanians understand Greek and almost all of them speak it. They have a Greek school for boys and a Greek school for girls. They call themselves Greeks, but there is no revolutionary Hellenism in them. Their political objectives are limited to reducing taxes, and to restoring just and good administration. They are and remain faithful subjects of the Sultan whose portrait hangs in a prominent place on the wall among the crowned congress of Europe, just under the holy icons, and between the king and queen of Greece.

When they call themselves Greeks, they intend thereby to distinguish themselves from the Bulgarians of Macedonia and the Catholics of high Albania. They have never wondered whether they would, one day, become subjects of King George or his son, but they were determined never to be Bulgarians like those in Roumelia, or Catholics like “the Jews of Mirdita.” Distant Bulgaria did not disturb them. They were simply afraid of Italian doings in the region that they suspected everywhere. They excused themselves for having been hostile when we first met. They thought we were Germans and secret agents of some European power. Many Germans come and go here, in the service of Bulgaria, Serbia, Romania and Austria. Last year, one of them came by to convert the Christians of Elbasan, but they showed him that an Albanian must first of all think of Albania and make his sons true Albanians. Instead of Greek schools, they needed Albanian schools, an Albanian priest and an Albanian liturgy, in short, they needed to become worthy of their fathers and their name, they needed to be Albanicized, to become true Albanophones.

What remains of the old Muslim prayer field (namazgjah) of Elbasan, with the last cypress trees (photo: Robert Elsie, March 1997).To this apostle called Weigand, the Greeks replied that Albania and savagery were the same thing, that they regarded Epirus as their country, and that Pyrrhus the Greek was their ancestor. As to language, they preferred to teach their children how to play a musical instrument rather than how to speak a barbaric language. As to being Albanicized, that is to say, living like savages, this was not at all to their taste. Their wretched fathers, in their ignorance, had led lives of misery, but they wanted get closer and closer to light, to civilisation and to Hellenism. And they did what they said. This year, they sent two of their sons to the University of Athens, one to study philology and become school director, and the other to study medicine and save them from the witch doctors among the monks and dervishes.

The Christians of the fortress make a living, but only just, from their shops in the bazaar, from their few olive trees and from loans they make to the Muslims. The bazaar, outside the fortress though right along the wall, consists of two rows of narrow shops that the Christians open every morning. In the evening they close them up and return to the fortress. The cleanliness of the shops and the good width of the streets surprised us somewhat. We almost thought we were in one of the towns of Greece, in Patras, Piraeus or Tripolis, with their straight streets and perpendicular, parallel avenues. We congratulated the prefect on this. Despite all of his zeal, his administration was, however, not at the origin of this cleanliness. It was fire that had done the trick, in 1877, 1880 and 1882. But the Turkish authorities and fire most often work hand in hand, as almost everyone in Albania believed. Following a fire, the authorities had the right to confiscate a pickaxe length of land from landowners, to build new roads. A good fire spared legal battles and much money, and the prefects made good use of this ally to clear the land. […]

The bazaar of Elbasan offers visitors little of interest but an abundance of fruit. Markets in French towns rarely offer such melons, the largest and finest costing us one or two metal coins (4 to 8 centimes). On the other hand, the fine Albanian arms that fill the bazaars of Shkodra and Kavaja by the hundreds are missing here entirely. The long iron rifles incrusted with jewels, mother-of-pearl and silver, pistols in chiseled copper and silver, daggers, cartridge belts, powder horns and knives shining on the backs and in the belts of their owners. The country is in such a state of anarchy that the very thought of going out unarmed could be fatal and, without money, one cannot exchange the old punt guns for more modern equipment. Good shooters claim, however, that there is nothing like the good old weapons and the armourers of Elbasan still repair and produce what is needed. [...]

On leaving the bazaar, we entered the verdant Muslim quarter. Our first visit was to the prefect, the mutessarif. Elbasan and its territory constitute an independent prefecture. The prefect depends directly on Constantinople, without the usual intermediary of a governor general (vali). He owes this privilege less to the size of the region or to the number of its inhabitants, than to complicated political circumstances. The ten to twelve thousand inhabitants of the region are difficult to rule over. The hatred that exists between the Christians and Muslims, between rival families of the same religion, and between peasants and landowners can break out at any time, meaning murder, fires, heads cut off, babies roasted, women raped, and farms devastated, all of this being known as “Albanian troubles.” In addition, a revolt in Elbasan would close off the gorge to Macedonia and would sever links between Constantinople and Albania. […]

The current prefect was an Albanian from Korça. People had complained to us about him for the last two days: “a fox” said the Muslims, “a wolf” said the Christians. One man brought the accusations together by calling him the “foxiest of the wolves.” These words proved to be right. The Bishop of Elbasan accused the mutessarif of stealing too much. As in the rest of Turkey, one speaks of “eating up” the taxes. The Christians, taken for what they were worth, intended to send an official complaint to the ministry. The mutessarif responded to these charges by saying, “Bishop, when I was learning Greek in Korça, I read in your holy book that one must not muzzle the ox while he is treading out the grain. Agop Pasha (the minister of finance, an Armenian) is a Christian and respects his God.” This Bible quotation (Deuteronomy XXV, 4) showed that this man knew Greek but he pretended he did not speak or understand a work of this Giaour language. He was even ignorant of Albanian and was the only man in Elbasan to speak Turkish, this loyal subject of the Sultan. […]

He was, however, very kind to us and showed great deference to our plans. He knew that France was a great kingdom, that Napoleon with the Turks had seized a great fortress from the Russians and that the Sultan loved the French. He would do all he could to facilitate our journey, with all of his gendarmes and sub-prefects. He was hesitant about bandits. The clans of Dibra were exchanging gunfire at the moment, but the Albanians had been killing one another for four hundred years now. He hoped that, if we travelled in a large and well-armed group, rapidly and in daylight hours, we could get from there to Monastir without incident. The kadi (religious judge) who was with us at that time could tell us more. He had come back from Monastir two months ago, taking with him a dozen or so gendarmes and three or four servants. None of these fifteen to twenty persons was attacked. […]

The Muslim quarter is inhabited by the Muslim aristocracy. It counts about 500 to 600 houses, with 2,500 to 3,000 individuals. All of the countryside to the north, west and south belonged to them. It was only in the mountains to the east that one could find autonomous, free villages, called kephalochoria or eleftherochoria.

The fortress and the bazaar were surrounded by large, fine wooden palaces of two to three storeys with galleries, latticework window and verandas. In their courtyards were plane trees and roses. The high surrounding walls prevented curious passers-by from seeing the women and gardens. […]

The most revered place in town is a large square, lined on all sides by a row of cypress trees. These large old trees constituted its four thick and lofty walls, with one sole entrance at the corner towards Mecca. Carpets and gold-painted wooden arcades adorn the minbar and the mihrab. This is no doubt the oldest mosque of Elbasan, the place where the first imam, on the evening of the conquest, called out to praise Allah. It is here that the Muslims still gather throughout the summer and at Ramadan and Bayram.

The Vlach quarter is right beside this verdant temple. The Vlach colony of Elbasan, like that of Peqin, is a hub on the Vlach trade route between the Pindus Mountains and Durrës. The Vlachs have their own church, their language and their schools. They live and marry amongst themselves. But their church was constructed in the same style as the Albanian church. Their clergy is Greek, and their liturgy is held in Greek. Even the flagstones in their cemetery are written mostly in Greek. In their two schools, for girls and boys, instruction is given in Greek. They themselves speak Vlach in their quarter but Greek or Albanian in the bazaar. They also send their students to the University of Athens. In short, they regard themselves as Greeks.

The same German apostle who received such a snub from the Albanians turned to the Vlachs and spoke to them of Greater Romania, of their Latin brothers, their Greek enemies, the oppression of their race and language, and of the tyranny of the Greek clergy. The Vlachs then seized him and took him off to the prefect as an agent of sedition. But this German had papers, documents that caused the prefect to release him immediately with humble excuses.

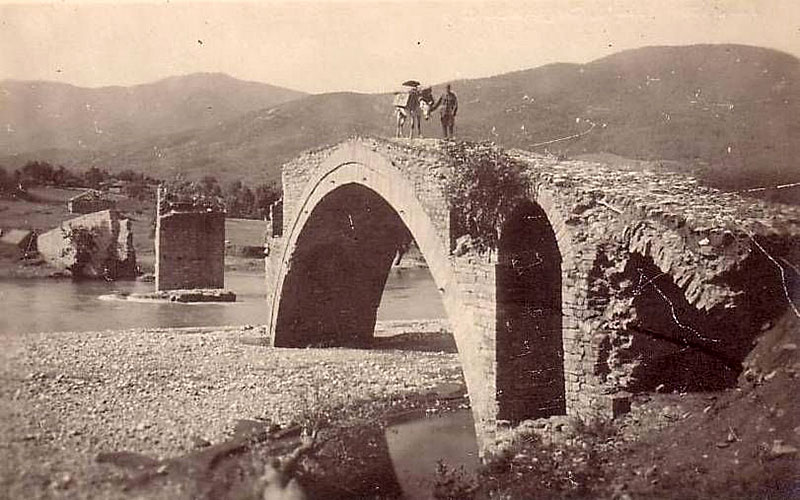

The twelve-arched Bridge of Kurt Pasha in Elbasan, constructed in 1780 and now destroyed.There are 150 to 200 Vlach families who live in the bazaar like the Albanian Christians, from trade, usury and olives. They have stone houses situated to the south of the Muslim town, along the banks of the Shkumbin, with little gardens of olive trees and melons. There is a long stone bridge, 60 to 80 metres in length, constructed in humpback form on twelve pointed elliptic arches of various curves. It leads from their quarter to the road to Berat. This, too, is a road like the one from Durrës, with cobblestones for the first hundred metres that then turn into a vague track until one reaches the hundred metres of cobblestones at the entrance to Berat. […]

We departed without telling anyone, in secret, at midday, the time when the bazaar was closed for the siesta. The streets of the Muslim quarter were deserted and all the doors in the Vlach quarter were closed. It was only when we got outside of town in the narrow shade of the earthen walls that we came across a line of women in red bloomers smoking their narghiles. Our sole escorts were our two loyal servants, Abeddin, the Muslim zaptieh, and Kostas, the Suliot Christian.

The remains of the Haxhi Beqari (Bachelor Pilgrim) Bridge over the Shkumbin River between Labinot and Miraka.From Elbasan to Struga, the first town in Macedonia, the caravans usually take two days and stop for the night at the han of Xhyra [Dchoura], but in order to cover our tracks, we preferred to spend the night in the gorge, at an isolated han at the side of the bridge of Haxhi Beqari (Hadji Vekkiari). This famous bridge is the only one on the lower Shkumbin that still had all its arches. An old bachelor (beqar) and pilgrim to Mecca (haxhi) had it built at the start of the century. […] It is always easier, safer and more normal to cross Turkish rivers under the arches rather than over the surface of the bridges. Custom has it so, as does prudence. Even when, by some strange coincidence, a Turkish bridge seems to offer guarantees of solidity, the surface on both sides is exceptionally steep and slippery, there are no railings, and its summit is at a dizzying height above the flowing water, among the leaves rustling in the breeze.

This fair and famous bridge was constructed at great expense by the Bachelor Pilgrim. It is set solidly on four pillars adorned with round niches and is only useful in normal times in Turkish fashion, that is, horsemen ford the river under its arches. It provides shade from the rays of the sun, which is all the more blazing around water, as one knows. Occasionally a pedestrian, a rare pedestrian (all Albanians have horses or donkeys) ventures over the bridge, for example when a rain storm has made the Shkumbin unfordable. Today, for instance, we were forced to use it in the European fashion, yanking our animals up one side and then holding them back on the descent. We were grateful to the Bachelor. The greatness of his bridge made us wonder about the greatness of his sins. We would have forgiven him for all the murders, robberies, rapes and ‘Albanian troubles’ he committed, had he added a good road, even a cobblestone one. […]

[Extracts from Victor Bérard: La Turquie et l’hellénisme contemporain (Paris: Félix Alcan, 1893, reprint 1911), pp. 1-75. Translated from the French by Robert Elsie.]

TOP