| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1892

Theodor Ippen:

Novi Pazar and KosovoThe Austrian scholar and diplomat Theodor Ippen (1861-1935) served at the Austro-Hungarian consulate in Shkodra from 1884 to 1893 and from 1895 to 1905, and travelled extensively in Ottoman Albania. In 1892 he journeyed through the little-known regions of the Sanjak of Novi Pazar and Kosovo, and left the following description of his trip.

Pešter and Rožhaj

To the south and southeast of Sjenica is the region of Pešter [Peshter] that is unusual both in its geographical makeup and in its population structure. Pešter borders on the current Sjenica-Novi Pazar road to the north, the regions of Bihor, Rožhaj [Rozhaje] and the foothills of the Rogozno mountain range to the south, Sjenica to the west, and the area over to the town of Novi Pazar to the east. This region is a high mountain plateau that rises to a maximum elevation of 1,100 m. above sea level. It is almost completely devoid of trees, but has very good pastureland. The plateau has an odd configuration because it is not one continuous plain, but rather a plain broken up like a honeycomb by a number of ravines. Some of these broaden into marshy valleys that disappear into gorges. In general, however, the plateau is arid, lacking water. Most of the villages are to be found in the valleys, the most important of which are Suhodol and Melaj.

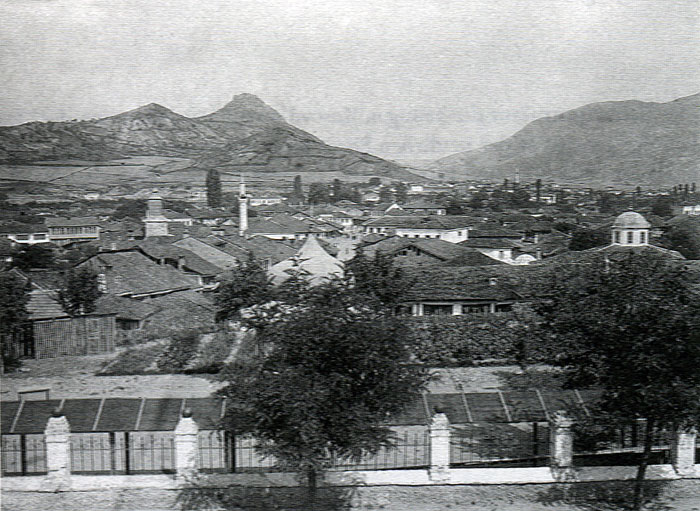

Mitrovica at the start of the twentieth century"

(Photo: Bildarchiv, Austrian National Library 155.681).

Up to the year 1865, Pešter and Rožhaj formed a district called Muduriye that was governed by the muselim [liege deputy of a vizier] of Suhodol under the pasha of Novi Pazar. When the vilayet of Bosnia was reorganized under Djevdet Pasha in 1865, Rožhaj was made a district (kaza) of its own called Trgovište, and Pešter was assigned to the kazas of Sjenica and Novi Pazar.

The region of Pešter is inhabited by a majority of Albanians, who emigrated here from their motherland in 1690 and 1737 when large portions of the native Serbian Christian population fled to Hungary with Austrian troops. This left great expanses of territory empty and attracted the Albanians who were living in cramped quarters in their native mountains. Pešter was the northern-most part of my expedition which continued eastwards to the plain of Kosovo and in the direction of Niš [Nish]. The Albanian population of Pešter forms a wedge in an otherwise Slavic region. They are surrounded by Bosnian Slavic tribes to the west and east, and are only connected with Albania, i.e. Ipek [Peja], on the southern side through the Ibar [Ibër] region near Rožhaj.

It is evident that tribal affinities among these immigrants are loose because settlement here did not take place by tribe, the main families having chosen their places of residence individually. However, all of the families remember which tribe or fis, they belong to, and the rights and duties that membership in this fis entails. They strictly respect the norms of their customary law that regulate life among them, just as the tribes living together in the motherland do. The Albanians of Pešter belong mostly to the Kelmendi and Kuči tribes. The Kelmendi stretch from their tribal territory in the mountains of Scutari [Shkodra] through the valley of Gusinje [Gucia] and Plava right to the Smiljevica mountain range. One can assume that the settlers in Pešter broke off from the Kelmendi tribesmen living on the border with Rugova. The Kuči, who now live in the western part of Kom in Montenegro and are now almost completely Slavic-speaking, come originally from the southern slopes of the Albanian Alps near Ipek where a number of Kuči families remained after emigration to Kom. Those who stayed behind now form part of the large eastern Albanian tribe of Berisha. The Kuči in Pešter, who have remained Albanian, thus probably moved there from their original homeland near Ipek. A small number of Albanians in Pešter belong to the Shala and Triepshi tribes.

These Albanians live among Muslim and Christian Slavs. Since they are dependent upon the markets in the Slavic towns of Sjenica and Novi Pazar, they have of course learned the Slavic language. They have not preserved their national customs in a pure fashion, and one can often see the influence of their Bosnian neighbours in them. Their costume is that of the Albanians of the district of Ipek. It consists of the çakshir, narrow trousers made of white felt with black woollen braiding, and doublets and jackets that are similar to those usually worn in Rascia and Herzegovina. On their heads, they wear the white Albanian cap called the çulah. Their weapons consist of revolvers, yataghan sabres, and breechloaders.

Landscape in Peshter, in the Sandjak of Novi Pazar

(Photo: Julian Nitzsche, July 2008).These Albanians, living far from their motherland, have managed to preserve the unyielding will for independence characteristic of their nation. Although they do not enjoy the same privileges they had on their original territory, they have never submitted to the administrative regulations in force in all the other provinces. Nor has the government ever succeeded in breaking their Albanian pride. The Porte has little authority over Pešter and is constantly being opposed. Government influence is nominal and is only tolerated to the extent that the measures in question find favour in the eyes of the Albanians and are voluntarily accepted. This is by no means an exaggeration. Since nothing has been done to accustom these people, even gradually, to law and order, it is evident that there is no way of checking their innate ferocity, unbridled by any legal constraints. Vendetta is ubiquitous among them and has led to never-ending feuds between families and their supporters. Whenever grounds for feuding are lacking, the restless spirit of these would-be knights-errant is vented in highway robbery, which is the plague of the road between Sjenica and Novi Pazar. The Albanians of Pešter are by no means less savage and rapacious than their notorious compatriots in the districts of Ipek and Djakova [Gjakova].

The district of Rožhaj, that the Turks call Trgovište, covers the upper reaches of the Ibar River as well as the northern slopes of the Žljeb mountains, Štedin and Mokra Gora. It borders on the Albanian regions of Rugova and Ipek and, as a result, has a much larger Albanian population than the Pešter region. The upper Ibar valley is extremely attractive, but it has little arable land. The major source of income for the district are, therefore, the mighty forests that cover the slopes of the Žljeb mountains. The people are heavily involved in the lumber trade and produce all kinds of boards, beams and oak crossties that are sawn on site and are driven, mostly as floating timber down the Ibar, to Mitrovica, where they are sold. The main settlement in this district is the little town of Rožhaj. The maps also show a separate town of Trgovište or Eski Pazar, but this does not exist. As mentioned above, Trgovište is simply the name used for the district and town of Rožhaj by the Turkish authorities. The peaks of the Smiljevica mountain range that extend into this district are used by the Rugova tribe and by some families of the Kelmendi tribe as summer pastureland. The latter, who are more usually at home in the mountains of Scutari, spend their summers here and indeed right to Rascia.

In addition to a small Christian population of Serbian tribes and Muslims from Bosnian tribes, the district is home to a substantial number of Muslim Albanians. These people, who immigrated here from the regions of eastern Albania, belong to the Kelmendi and Kuči tribes and, to a lesser extent, to the Hoti, Shala, Gashi and Krasniqi tribes. They are similar in all respects to the tribesmen in the district of Ipek, but have no close contact to them. Rather, they maintain close ties with Mitrovica, both town and district, where the Albanians constitute a major portion of the population. […]

Mitrovica

The town of Mitrovica, which is of substantial military and political importance, is finely situated at the northern end of the plain of Kosovo, where the main river, the Sitnica, coming from the south, joins the Ibar flowing in from the west. Although the larger river that results from the union of the two smaller ones continues in the direction of the Sitnica and it thus looks to the eye as if the Ibar were its tributary, it is actually the latter river that gives its name to the confluence of the two rivers because it is by far the larger of the two. Right next to Mitrovica is a long gorge through which the Ibar, constricted by the Rogozno and Kapaonik mountains, flows towards the Serbian border near Raška [Rashka]. A modest trail leads through the gorge to the border post.

The town is built on the right bank of the Ibar, and the Sitnica is about one kilometre away as is the spot where the two rivers flow together. A dirty little creek called the Ljušta [Lushta] flows through the town, coming down from the Çiçavica mountains. To the north of the town rises the hill fortress of Zveçan, near which a smaller cliff-like promontory rises. South of this are foothills that descend in waves from the Čičavica [Çiçavica] mountains to the Sitnica, and divide the town from the railway station. From here, one can see the whole plain down to its end at the Gorge of Kačanik [Kaçanik] in the south.

Mitrovica is a small and unattractive town. Through it runs a wide street straight from the Ibar bridge to the above-mentioned foothills, on the two sides of which cluster the various neighbourhoods. It is in this street that one finds the çarshia [bazaar], and the main mosque (the town possesses two other large mosques and one small one), as well as several inns, one of which is slightly better than the local average. It offers modest accommodation to European travellers. The streets and squares in the mahallas [neighbourhoods] are, of course, not paved, but there are a number of attractive, larger houses which are proof of a certain prosperity enjoyed by the inhabitants. The manner of construction is different from that in Bosnia, that is preserved in northern Rascia. It is more in tune with the type of construction encountered in Macedonia, more influenced by Constantinople. Here one finds brick walls in a timber framework, with many large windows, including bay windows and overhangs.

The foothills to the south of the town are home to various military buildings that are in a desolate state: the command called the firka, barracks, sheds for artillery and ammunition, and the military hospital. Behind these are the cemeteries of the town which reveal many large gravestones. In half-an-hour’s walk along the left bank of the marshy Sitnica one reaches the terminus of the railway coming up from Salonica. […]

The Plain of Kosovo (Kosovo Polje)

Kosovo Polje – the Plain of the Blackbirds – comprises the entire political districts of Priština [Prishtina], Vučitrn [Vushtrria] and Drenica. To its southernmost part belong the districts of Gilan [Gjilan] and Üsküb [Skopje]. The capital of the whole region is Priština.

Priština is situated at a site where the Prištevska rjeka [Prishtevka River] enters the plain near the eastern edge of the plain of Kosovo at the foot of a range of hills that extend southwards from Mount Izvor on the Serbian border. The hills behind the town are of medium height and soft in contour, but are barren with the exception of some grass and a few bushes because the forests that once covered them were all foolishly cut down, as would seem to be the fate of trees in the vicinity of almost all Turkish towns.

The Prištevska rjeka that flows through the town is but a tiny creek for most of the year, but it can flood tremendously and, when it does so, it causes great damage to the town. One such sudden flood occurred in September 1889 which churned up the paving of the streets near the river, carried off many mud huts and wooden houses, and destroyed other homes built of stone. One reason for these unexpected violent floods is to be sought in the clearing of all the forests up behind Priština.

Priština is not an old settlement in its current form and location, but the region surrounding it was always a favourite site for settlements. The initial settlements date from the time of the Romans who first brought civilisation to this corner of the Balkans. The Roman road from Lissus to Naissus [Lezha to Nish] that led over the plain of Kosovo included a station called Vicianum. In the opinion of Hahn (Reise von Belgrad nach Salonik), Vicianum was situated near the village of Čaglovica [Çagllavica], about one hour south of Priština. According to what I was told by the inhabitants, there are ruins of an ancient town in the mountains two to three hours east of Priština, which are said to be the forerunner of modern Priština. They probably date from the time of the Serbian Nemanjić dynasty. This was their residence after Ras Novi Pazar, and King Milutin (1275-1321) is said to have built a palace there, of which the walls and a tower were preserved until very recently. These last remnants of the town’s great past have now disappeared. On the site of the one-time royal palace is a government building that used the said ruins when it was constructed.

Fushë Kosova (Kosovo Polje),

the mausoleum of Sultan Murad

and the grave of the Grand Vizier Rifaat Pasha"

(Photo: Gabriel Louis-Jaray, 1909)There is nothing special to see in modern Priština. It looks like any provincial town in Turkey. It is a jumble of houses, mostly made of wood and mud, as well as a very few houses made of stone. It has narrow and very badly paved streets that are grouped around the bazaar in the middle of the town. The bazaar of Priština is of no particular interest. The shops, few as they are, offer the usual consumer goods but no notable local specialities. The Circassians [Cherkess], who were settled on the plain of Kosovo in large numbers, produce tasteful objects of Niello inlay, in particular handles for daggers, sheathes, and silver-plated whip stocks, but they have no shop in Priština and only produce the objects on commission or bring their products into town on market days. The main street of the bazaar stretches from west to east. At the eastern end is the Bazaar Mosque, founded by Sultan Murad II (1421-1451) and completed by Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror. There is also a clock tower and a government building, a simple two-storey construction. There are two other larger mosques that are worthy of mention: the Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror Mosque and the Jashar Pasha Mosque. The Christian community has only one church that is hidden away. To the south of town there are barracks and military buildings for the use of infantry and cavalry, as well as a steam mill.

Priština is the seat of the mutessarif. The Sanjak of Kosovo that he oversees is not limited to the plain of Kosovo but includes several neighbouring regions, such as the districts of Mitrovica, Gilan [Gjilan] and Preševo [Presheva]. The town has 21,000 inhabitants, of whom about 16,000 are Muslims and the remainder are Christians who – with the exception of some Albanian, Vlach and Greek immigrants – are of Serbian Orthodox faith. There are, in addition, a small number of Jews here. The Christians, with the exception of the above-mentioned immigrants, all speak Serbian. As to the Muslims, some of them speak Serbian, but most speak Albanian.

Priština is also important as a junction of the roads leading across the plain of Kosovo. To the northwest, in the same direction as the plain itself, is the road to Mitrovica. Just outside of Priština, it crosses the foothills of the nearby mountains. At half an hour’s distance, on a slope on the right side of the road, there is small unadorned mosque that contains the grave of Gazi Mestan bey who was the flag-bearer of Sultan Murad in the battle of Kosovo, where both of them lost their lives. A quarter of an hour further on, near a little creek on the left side of the road, one comes across the mausoleum of Sultan Murad himself. Here there is a small domed mosque in a courtyard surrounded by walls. The floor is covered in precious Smyrna carpets which the current sultan donated several years ago. The walls bear inscriptions with the names of the caliphs and with religious sayings in calligraphic script. The tomb itself is in the middle of the mosque and is covered with brocade cloth from Bursa in which verses from the Koran have been inscribed. At the head of the tomb is a wooden stave with a huge turban of white muslin on it. However, the mausoleum only contains the heart and intestines of the sultan that were left here when he was embalmed. The body itself was transferred to the residence in Bursa. Buried at the entrance to the mausoleum is Mushir Rifat Pasha who died suddenly in 1853 on the expedition to Sofia and the Danube to fight the Russians. The mausoleum is attended by a türbedar (grave keeper) who lives next door.

From here on, the road stretches across the completely flat plain between the hills of Priština and the Sitnica River for an hour until one reaches the Lab River. It was on this inconspicuous soil, now devoid of human habitation with the exception of two Circassian villages, that destiny was once written, when a brave people struggled for their independence. It is an historic site that one treads upon with great emotion, for it was most likely here that the Battle of Kosovo was decided. It was here that the two opposing armies met and did battle with equal bravery but with an unequal outcome for crescent and cross… There is a bridge crossing the Lab River but it is in such a bad state that horse riders will prefer to ford through the water. There is an inn at the bridge called Babinos after the nearby village. From the veranda of the inn one has a tremendous view of the whole expanse of the plain of Kosovo. The origin of this curious village name (babin nos = nose of the old woman) derives from the following legend: After murdering the sultan, Miloš Obilić fled to this spot. Here, an old peasant woman toppled him from his horse by slicing off the animal’s pasterns and handed him over to the janissaries who were pursuing him. When Miloš realised that his time was up, he called the old woman over to him on the pretext of wanting to whisper a last wish into her ear. Instead of this, however, he bit her nose off (babin nos). It is in memory of this event that the village bears its name.

From the bridge over the Lab River, and following the course of the Sitnica River, the road reaches the small and insignificant town of Vučitrn in two hours. It is inhabited by a rather fanatic and unbridled population of Muslim Albanians. Beyond Vučitrn, the road crosses the Sitnica over a stone bridge and leads to Mitrovica in two hours.

The road from Priština southwards, also in the same direction in which the plain of Kosovo stretches, leads to Kačanik and thereafter to Üsküb. On its way, it crosses several tributaries of the Sitnica and in two hours reaches the Christian village of Lipljan [Lipjan] on the Sitnica, where there is a railway station. The old Serbian church here dates from the time of the Nemanjić dynasty. The main road follows along the Sitnica to the station of Rubovce [Rubofc] which is one hour away. It then crosses the marsh of Sazli and enters the valley of the Neredimka [Nerodime] River in the direction of the settlement of Kačanik (in four hours), where a long gorge begins that leads to the plain of Üsküb [Skopje].

In Lipjan, there is a road that branches off to Prizren. It crosses the Sitnica and continues over the plain for one and a half hours to the settlement of Stimlja [Shtime]. Here it meets a road coming from Ferizović [Ferizaj] that serves as a connection between the railway station and Prizren. From Shtime, the road leads up through the gorge of the Crnoljeva reka [Caraleva River]. Then comes the village of Crnoljeva [Caraleva] with two inns. From this village, the road continues upwards along the left side of the valley to the divide and a pass called Čafa Duljit [Qafa e Duhlës] named after a village on the other side. This is the border with the district of Prizren, as well as the divide between the plain of Kosovo and the plain of the Drin [Metohia]. Although the pass is not very high, it provides an excellent view of the splendid surrounding countryside. The viewer can observe the whole expanse of the plain of the Drin gilded in the sunlight, an extraordinary view. To the left stretch the nearby snow-covered fields and slopes of the Šar [Sharr] mountains that rise proudly up into the azure firmament. At the end of the range rises the sombre peak of the Gjaliča Ljums [Gjalica e Lumës]. On the other side of the plain of the Drin are the rocky Alps of Djakova, unknown and unexplored. To the right in the background one can even see the snowbound peaks behind Ipek that form the edge of the plain.

From Priština westwards, along the southern bank of the Drenica, there is a horse trail leading to the village of Lozince which is at the divide between the plain of the Kosovo and the plain of Metohia. Here it separates into two, one branch leading to Djakova and the other to Ipek.

North of Priština is the road to Serbia which follows the valley of the Lab creek until it reaches the border post at Karaula Prepolac. On the other side of the border, the road continues along the valley of the Toplica to Nish via Kursumlje [Kuršumlija] and Prokuplje.

The road from Priština to Gilan crosses the Graçanica [Graçanica] creek, an eastern tributary of the Sitnica, about one hour away from Priština. The village of the same name is situated on both banks, and on the left bank is the monastery with the famous church. The buildings of the monastery are simple, low constructions in local style that house the monks and their tenants who do the farming. In the midst of the courtyard is the church that is well preserved despite its age, a fine, impressive building of the Nemanjić age which is most certainly among the most important monuments of that great period of Serbian history. The church consists of a low vestibule (chalcidicum) and the taller main church. Hahn described it in detail as follows in his work Journey from Belgrade to Salonica: “Each of its four fronts is divided into three sections, of which the lowest section consists of three round arches, the central one being one and a half times the size of the other two. Above each of these central arches is a second section made up of four pointed arches. The rectangular shape they make bears the third section, which is the main dome. In the corners made up by the outside round arches, are four secondary domes.” The main dome and the four surrounding smaller domes are the characteristic element of the whole building that makes it rise strongly upwards and look very high. The impression given is stressed all the more by the colourful façade: yellow stonework, red bricks and heavy grey mortar. One enters the building through a narthex, a plain, low room. On the right side is an old baptismal font with a Roman inscription on it. The interior of the three-aisled church is small and, when one stands under the main dome, it thus appears higher than it is in reality. Beautiful old frescos cover all the walls. Near the entrance to the main nave, on two columns, are the builder of the church, King Stephen Milutin (1275-1321), and his wife, the Byzantine Princess Simonida, both portrayed in rich Byzantine robes. The king is seen holding a model of the church on his right arm. Most of the other frescos are of saints.

An hour down the Gilan road on the left side is the village of Janjevo [Janjeva] inhabited by Catholic Serbs and consisting of 300 Catholic families. A few Catholic families also live around the villages of Androvce [Androfc/Androvac] and Popas. These three communities make up the parish of Janjevo that is part of the diocese of Üsküb. The parish church is located in Janjevo. These Catholic Serbs, good and industrious people that they are, are mostly metal casters who struggle to make a living, but do so honestly, by manufacturing rings and small bits of jewellery made of non-precious metals and by selling the objects to the surrounding peasant population. There is another Catholic parish in the district of Gilan.

Two interesting areas of the plain of Kosovo have not yet been mentioned in our travels in and around the country: Drenica and Kačanik.

Drenica is a long valley through which the Drenica creek, a tributary of the Sitnica, flows. It forms the northwestern part of the plain of Kosovo and stretches from the left bank of the Sitnica westward to the divide and border with Metohia. The region also includes the mountain ranges on the two sides of the valley, one stretching down towards the plain of Metohia and others towards the plain of Kosovo. The Drenica region is situated between the towns of Mitrovica, Priština, Ipek and Djakova. The main settlement is called Lauša [Llausha], which is in fact a large village. Drenica is a relatively fertile region. Although the trail from Mitrovica to Djakova passes through it and it is thus connected to more accessible regions, Drenica has not yet been visited by any European travellers and is therefore virtually unknown. One reason for this is the particular population. Drenica is inhabited primarily by Muslim Albanians, with a minority of Christians. Until very recently, the Albanians of Drenica managed to keep themselves free of government interference and lived in virtual independence, with their own customs and traditions. In their struggle for independence, they received substantial support from their co-tribesmen in the regions of Ipek and the Ibar valley. The ever-patient Porte put up with this “republic” for as long as its disrespect of government authority remained passive. However, in the summer of 1890, when the Albanians of Drenica exhibited extraordinary violence against the Christian inhabitants of the region and openly resisted government orders, the authorities realised they needed to take more energetic steps and turned their attention to this forgotten region. Drenica was then re-organized as a district of its own and was provided with all the requisite organs of administration. However, it can be assumed that the people of Drenica, who did not look happily upon the loss of their autonomy, will find ways and means of reaching an agreement with the government so as to make the transition to a new order as painless as possible. In view of the situation as described here, there are great gaps in our knowledge of this area.

Kačanik, the southernmost part of the plain of Kosovo, is a small town and seat of a mudir, whose superior authorities reside in Üsküb. The settlement, inhabited by Muslim Albanians, is situated on the left bank of the Lepenac [Lepenc] River near the point where the Nerodimka River flows into it and is divided by the railway line. To the right of the railway embankment rises the old fortress of Kačanik, of which only the walls supported by a few towers have survived.

Very interesting and virtually unexplored is the upper valley above Kačanik and source region of the Lepenac. It is surrounded by the main Šar Dag [Sharr mountain range] with Mount Ljubotrn [Lybeten] and by the Kodjabalkan [Bjeshkët e Jezercit] range to its eastern most part, Jezerce. The region is said to stretch in that direction for about six hours. The Serbs, who form the majority of the population there, call it Sirinička župa or Siriniče.

The railway line passes through the valley of the plain of Kosovo, following the bed of the Sitnica River. This railway is part of a stretch that, in accordance with the railway convention of 1869, was to link Üsküb and Sarajevo and then lead up to the Austrian border on the Sava River. The subsequent convention of 1872 limited the construction of the rail line to the stretch from Üsküb to Mitrovica, which was completed and opened by the Society of Eastern Railways [Gesellschaft der orientalischen Bahnen]. However this railway does not have any of the lively and hectic traffic of a western European steam rail line. It runs in a spirit of lethargy and imperturbability Three passenger trains run from Üsküb to Mitrovica per week (Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays) and return from Mitrovica on the following days (i.e. Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays). When the new rail line made its way through the Lepenac Gorge, which involved the construction of many tunnels and bridges, and is a very interesting part of the country, it reached its first stop in Rascia in Kačanik. From here, there is a gradual descent until it gets to the next stop of Ferizović, the railway station for Prizren. This station is also of some importance for the transport of troops and ammunition. Thereafter come the stations of Rubovce, Lipljan, and Priština. The latter station is seven kilometres from the town. This was because, at the time of construction, the uncivilized inhabitants of Priština strove to keep the modern “diabolical invention” as far away from the town as they could. Now they are constantly clamouring for a line into town. From Priština, the railway line continues on to Vučitrn and ends in Mitrovica.

[Extract from: Theodor Ippen: Novibazar und Kossovo: das alte Rascien, eine Studie (Vienna, Alfred Hölder, 1892), pp. 111-115, 139-140, 144-154. Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.]

TOP