| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

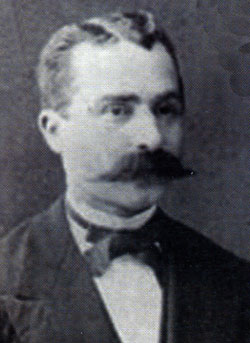

Kurt Hassert (1868-1947).

1897

Kurt Hassert:

Excursions in High AlbaniaThe German geographer Kurt Hassert (1868-1947) was born in Naumburg on the Saale, south of Halle, and studied in Leipzig and Berlin. He taught in Leipzig (1895-1898), and was professor at the University of Tübingen (1899-1902), at the College of Commerce in Cologne (1902-1917), and at the Technical University of Dresden (1917-1935). Shortly before his death, he returned to the University of Leipzig (1947) where he died. Kurt Hassert is remembered for his research on the polar regions, Africa and the Balkans. Among his Balkan publications were: “Reise durch Montenegro nebst Bemerkungen über Land und Leute” (Journey through Montenegro with Remarks on the Land and its People), Vienna 1893; “Beiträge zur physischen Geographie von Montenegro” (Contributions to the Physical Geography of Montenegro), Gotha 1895, and several articles devoted to Albania. One of these articles, “Streifzüge in Ober-Albanien” (Excursions in High Albania,) describes his travels through the mountains of northern Albania in 1897. Hassert, as will be seen here, was more impressed by the natural environment than by the ‘human geography.’

The Chieftains of Mirdita

(Photo: Marubbi 1875).

Travelling in High Albania is not as easy as in neighbouring Montenegro. There, no government endeavours to hinder foreigners from travelling and one can wander around safely among the poor but guileless population. In addition, the little principality has a good number of well-maintained roads and trails, and the plateau character of the country means that, although it is not exactly conducive to travel, one can journey for hours or even days without encountering any major impediments. The situation is completely different in Albania. In their timidity, the Turkish rulers do all they can to make it difficult or impossible for foreigners to enter the country. If the affection that the German Emperor holds for Turkey and the important activities carried out by German officers in the Turkish army and in the Greek-Turkish War in general were not so well known, I would certainly have encountered as many problems as did Dr Baldacci who, due to the pro-Greek proclivities of Italy, only received his travel permission after three applications made for him by his country’s diplomatic representatives. In addition to this, the Albanian highlanders are a savage bunch, an unruly people who are averse to any government order or higher civilisation. Because of their blood feuding, their constant war making among one another and with the Montenegrins, and because of their many uprisings against the Turkish pseudo-government, they are accustomed to enjoying robbery, murder and warfare as their preferred hobbies. If one wishes to visit a certain region, one must first inquire about the mood of the inhabitants and make friends with a member of the tribe in question, or at least get advice from a widely respected parish priest. These clergymen proved to be of invaluable assistance to us. Their parsonages, where we enjoyed their hospitality, were little islands of civilisation in a sea of complete barbarity. At other times, we had to put up with incredibly primitive board and lodgings, not to mention the miserable trails we hiked up and down day after day. Because there is no constant traffic on them, the local trails are in a pitiful condition. The topography of the region also makes travel extremely difficult. High Albania is one of the most isolated regions of European Turkey. Nowhere does the coastline penetrate far into the interior. In order to get to the extensive basins of the interior, one has to set out from the coast and climb numerous mountain ranges. The Dinaric Alps cover most of the interior of the country in a baffling network of deep valleys and gorges and lofty mountains that can only be crossed over rare mountain passes or Chafas [Alb. qafa ‘pass’]. One is often forced to cross two or more of these Chafas in one day. The descent down the steep bush-covered mountainsides is just as exhausting as the hours of upward climbing. Man and nature come together at once in High Albania to sap travellers of their physical and mental energy. For this reason, we broke our travels into smaller portions instead of doing all at once. Once we received all the authorisations and official recommendations that we needed, we kept Shkodra as our base and divided our travels up into nine different excursions, some short, some long.

The first journey, or the fourth if we count the earlier short excursions, was to Mount Cukali. We left Shkodra on 15 June [1897] and after riding over the fern-covered plains for several hours where there was little agricultural activity, we reached a side valley of the Kir River with its colourful shale. Its dense forests consisted in the lower regions of chestnuts and oak trees and in the upper regions of beech trees. That evening we crossed the narrow ridge of Mount Cukali and descended into a deep ravine which was still full of snow despite the advanced season. We set up camp in a solitary clearing, made a roaring bonfire, wrapped ourselves up in our blankets and coats, and fell asleep. We had just nodded off when a suspicious noise caused us instinctively to grab our rifles which we always kept cocked by our sides because of general risks and of the numerous bears and wolves in Albania. It turned out simply to be some branches snapping, but we nonetheless held guard until dawn and were relieved when the scary night was over.

It was a chilly +6 C. degrees when we set off in the morning. After two hours of difficult climbing, we reached the peak Maja e Mylesife that was just above the treeline and offered a splendid view of the distant mountains of southern Albania and the lofty slopes of the northern Albanian Alps right in front of us. We enjoyed the same wild beauty when we reached the second peak, the 1,841 m. high Mount Cukali. We spent that evening in the village of Vukaj and returned to Shkodra on the third day through territory with which we were now familiar.

We began our third excursion with a two-day climb – alas in the pouring rain – up the 1,576 m. high Mount Maranaj, a journey that was to take us through Mirdita country to Prizren. We left our base in the rain on 24 June and rode along the Drinasa River over the monotonous plain. We crossed Albania’s largest river, the Drin, on a primitive ferry that consisted of two dugouts attached by crossbeams. Here on the left bank began Mirdita land. The Catholic Mirdita are the most populous tribe of the highlands and have managed to wrest a whole series of privileges from the Sublime Porte. They live in complete autonomy and, like the other independent mountain tribes, will not suffer the presence of any Turks on their land. Only in wartime are they obliged to provide troops, although Christians in Turkey are otherwise exempt from military service. Indeed, they enjoy the dubious honour of fighting on the right wing of Turkish forces, whereas the Hoti tribe, also Catholic, has the same privilege for the left wing.

We had difficulty finding a suitable guide. The fellow that we had been more or less obliged to take with us from our first camp at Gomsiqja to Kashnjet demanded the exorbitant sum of four medjidie or 16 marks in advance for two days and abandoned us on the first evening, of course taking his full wages with him.

Preng Doçi, also called Primo Docci

(1846-1917).

On our third day, after an exhausting 16-hour march that took us along steep trails up and over four mountain passes and, each time, down into deep valleys, we reached Orosh, the capital of Mirdita, and were graciously entertained by the abbot. His Eminence Primo Docci [Prengë Doçi] is an extremely interesting and politically important figure – the real king of the Mirdita region. He is a true son of the Albanian highlands, although he received a comprehensive education and much experience from twelve years of spiritual activity in North America, India and Europe. I was quite amazed and delighted, in this isolated and barbaric land, to hear him reminiscing about Germany and in particular about the beer in Munich. Under the protection of armed guards, we journeyed over the broad forested ridges of the wild and karstic Nan Shenjt. Dr Baldacci then returned to Shkodra by another route and I carried on inland. The considerate abbot was kind enough to have a clergyman accompany me to the border of Mirdita, and this measure of precaution was by no means superfluous. As we later learned, one of the bajraktars of a region we passed through had followed us with the intent of robbing us. He would have seized upon the collection of topographic sketches I had made on my journey. Because we were quite a ways ahead of him, we were able to get away, but in actual fact, things only got more dangerous from then on because we had entered the region made insecure by the Luma tribe. We were greatly relieved when we finally reached the Shkodra-Prizren trail. We continued up the narrow valley of the Drin on a terrible trail until the gorge suddenly opened up onto a broad plain and, several hours later, we reached Prizren. I enjoyed three days of kind hospitality with the Austrian consul, Mr Rappaport, and, because of Germany’s political prestige here, I was very well received by the authorities and the population. The mutessarif, Muharrem Bey, soon paid me a return visit and I even received a telegram of welcome from the Governor General of the province in Skopje.

Prizren is situated beautifully on the northern side of the Sharr Mountains. It rises from the extensive flatland like an amphitheatre snuggling into the hills above. The upper town, that holds the Austrian and Russian consulates as well as government offices that are used as nests by the countless storks who feed in the surrounding marshes, offers a splendid view over the lower town with its 25 minarets and over the plains that stretch up to Peja and Gjakova. Crowning the town is a large fortress and behind it, looming over a deep gorge, are the ruins of the legendary White Castle of Prizren where the Serbian hero Marko Kraljević once sat with his falcons and drank brandy.

Despite its narrow lanes and unsightly houses, Prizren is one of the wealthiest and most industrious towns in the Orient. It even possesses an aqueduct and its inhabitants excel in producing leather goods and shoes, and in engraving and embroidery work. Commerce has unfortunately been severely impeded by the constant raiding and pillaging of the Luma tribe and its once flourishing trade has also suffered greatly from the opening of the Macedonian railway. There is no prospect of promoting trade here because the normal rate of interest is 20%.

Prizren is larger than Shkodra for it has 36,000 to 40,000 inhabitants – Serbs, Albanians and Vlachs who are Greek Catholic, Roman Catholic and Muslim. Islam is now by far the majority religion. Whole tribes that were formerly Christian have converted over time. With the continuing Albanization and Muslimization of the once entirely Christian and entirely Slavic Old Serbia, the Albanian language is much on the increase, despite the propaganda spread by the Kingdom of Serbia. Among the Muslims, however, there are many crypto-Christians who are outwardly devoted to the Prophet and have Turkish names, but are secretly Catholics. The Albanian Christians are, for their part, only Christian by name. Their thinking and actions are governed by profound superstition, for instance by a fear of the night, of witches and of ghosts. The branches of certain trees are weighed down with stones to drive away evil spirits. One can protect oneself from witches by spells that will entrap them in sacks hanging from the window that are then thrashed or burned. Since very few of them understand anything of the real teachings of Christianity, no one sees any problem in killing a person. As an example, the parish priest of Abat later told us that one of his flock had earnestly entreated the Lord to help him murder his uncle. He then lay in ambush and, having accomplished the dastardly deed, fervently thanked God for his gracious assistance. On the other hand, as to showing off one’s religion, there are no more zealous and fanatic Christians than the Albanians. They pay greatest attention to observing all the external trappings of the faith. Despite this, holy mass is often devoid of solemnity. The many children that are brought in to attend the church services chatter as they will throughout the ceremony and throughout the sermon. Things were so noisy in the church at Prizren that one of the clergymen did not regard it as beneath his dignity to put one of the loudest lads over his knee and give him a good spanking in front of the whole congregation.

I was sad to leave Prizren as I set off on the main trade route back to Shkodra. The miserable track leads initially across the plain and then, getting worse and worse, it follows down the Drin. The valley widens only once where the Black Drin flows into the White Drin and then narrows to a gorge that is almost impossible to get through. Together with the gorge of the Cijevna [Cem] River on the Albanian-Montenegrin border, this is one of the greatest canyons of Europe. At Han Spas, the trail leaves the river which takes a large turn to the north, and continues uninterrupted over hill and dale. It makes its way over the desolate serpentine plateau of Puka and, after an endless number of bends down the valley of the Gomsiqja River, it arrives at the plain of Shkodra. Dense forest covers many section of the trail, mostly oak but also beeches, evergreens and high boxwood shrubs. Geologically speaking, the Drin region is made up primarily of limestone, diorite and serpentine. The latter is quite common and can be seen at a distance with its hues of green and brown and the meager vegetation.

Although the trail has lost much of its significance because of the Macedonian railway, it is still of importance because it is the only connection between the interior and the coast, and Turkey is, of course, intent on keeping it open. The mountain tribes are eminently aware of this and know that the best means of putting pressure on the Porte during their frequent uprisings, is to cut off the route for all traffic for a while. Many inns or hans offer dubious accommodation to travellers and since much is lacking in the way of security, blockhouses have been constructed between them and are constantly guarded by gendarmes. The gendarmes protect and accompany travellers from one post to the next. Nothing says more about the situation in High Albania than the fact that I was accompanied by a total of 48 gendarmes and local guides on my two-week trip from Shkodra to Prizren and back, minus the three days I spent in Prizren. Along the trail there are numerous cairns or heaps of stones showing the places where travellers were murdered. But we had no difficulties and only glimpsed a few suspicious individuals in the bushes of the Gomsiqja Valley who communicated with one another with vaguely audible whistles. Among them was the guide who had abandoned us at the beginning of our journey.

Our eighth excursion took us to Mount Parun and gave us a taste of what the Albanians Alps, the object of our interest, were really like. We climbed endless switchbacks up the trail to an elevation of 1,400 m., and this in the blazing heat, until we reached the Bishkas Pass. On the other side of the pass, we had to climb 800 m. down the slope to get to the home of the Bishop of Pulat, a clergyman born in Trent.

Many of the Albanian parishes are run by Austrian and Italian clergymen. A new generation of Albanian priests is currently being trained at the Jesuit College in Shkodra. Just as Russia serves as protector of the Greek Orthodox, so does Austria protect the Roman Catholic Christians in Turkey and spreads successful political propaganda under the cloak of religion by means of the parish priests it pays. This explains why the portrait of the Austrian Emperor Franz Josef is to be found hanging in all the parishes, whereas the portrait of the country’s actual monarch, the sultan, is extremely rare. Austrian propaganda is directed both against Italy and against the southern Slavic movement. It is well known that Serbia and Montenegro are in cahoots with Russia to push Austria out of the Orient and restore the old Greater Serbian Empire. Just as Austria is a firm opponent of the Greater Serbian ideal, so are the Albanians bitter enemies of their Greek Catholic neighbours and reject any thought of Montenegrin rule. It was therefore a good idea to win over the Albanians and thereby strengthen Austria’s presence in the Adriatic Sea. Although, because of the lack of good harbours on its eastern coast, Italy ought to be striving to win over the Albanians on the other side of the Adriatic as allies for political and economic reasons and thereby ensure a counterweight to Austria’s growing influence, it has up to now limited its presence to some schools and its consulate and has allowed Austria to gain a substantial lead.

The trails got worse and worse and we proceeded for most of the first day on foot. When we got to Plan, we therefore sent the horses back to Shkodra because they had not been of any assistance and were indeed hindering our progress. From this point, we had our baggage carried by porters. The terrain is too difficult and the natives are simply too poor to keep horses themselves. In many settlements there are no beasts of burden at all. As such, they are replaced by human beings who lug all the heavy baggage up and down the perilous trails for hours without showing any particular sign of exhaustion.

We then reached the territory of the rapacious Shala who are feared for their savagery, and this for good reason. We were not received hospitably. The moment we got through the dense deciduous forest and reached Bosh Pass, we were attacked by robbers and ‘welcomed’ with bullets that whizzed by. As there were six men in our party, our people set off on the attack, led by the audacious Nikola. It was only with great difficulty that we managed to restrain them from doing things that would have resulted in blood feuds and made the continuation of our journey quite impossible.

Fortunately, our foes did not bother us anymore and simply observed us from a distance. As such, we were able to proceed carefully and unimpededly down the 1,000 m. slope to the floor of the Shala Valley. Snow-covered peaks bordered it on the other side, and, to our left, rose the lofty peaks of the Albanian Alps in their wild majesty. The contour of this little known mountain range was quite different from that of the mountains we had passed through up to then. Due to the prevalence of shale, the earlier mountains were dark in colour and were covered in forests and high pastures almost up to their peaks. Here, it was limestone that prevailed, and the karst process that is typical of limestone ranges. Since the steep mountain ridges were well above the treeline, the cliffs could be easily seen from a distance in light grey and with their extraordinary rough crests, below which were light-coloured coverings of debris and patches of snow. The natives called this sombre range of mountains the Mali i Shqipnisë or the Albanian Alps. In actual fact, they have various names for them, for instance, Parun, Maja e Elbunit, Biga e Gimajt, Maja e Pejës, Bjeshkët e Nemuna or Prokletije, etc. A number of the fifty loftiest peaks are over 3,000 m. high.

In general, the mountain ranges of northern Albania make a severe rather than pleasant impression on one. Here, within a small geographical territory, one encounters a great contrast of high and low, of harsh and warm climates, of frightening desolation and thick forests, of coniferous and deciduous vegetation, and of Mediterranean and Alpine climes. In the deep valleys one finds chestnuts, grapevines, figs, pomegranates and other Mediterranean plants, whereas beech forests predominate up in the mountains. The treeline was clear and evident, in clear contrast to the patches of snow.

The Young Warriors of Shala

(Photo Kel Marubbi, early 20th cent.).

In the poor, scattered settlements, we were pestered and annoyed by the shameless begging and impertinence of the inhabitants. Everyone owned a rifle, but no one owned a shirt. They seemed to change their clothes only when the garments fell off their backs. As a result, they live in incredible filth and the lack of hair on their cleanly shaven heads made their savage and ugly faces look even worse. We were greatly relieved when we got to the clean parsonage of Abat and were heartily welcomed by Father Camillo, a knowledgeable Franciscan from Austrian Trentino. The venerable priest runs one of the most thankless and dangerous parishes because blood feuding is particularly rampant among the Christian barbarians of Shala and their no less savage Catholic and Muslim neighbours. Only the church offers asylum and refuge, but there are also specific trails where one can travel in safety without being shot. Those who leave the said trails are, however, in mortal danger.

The next day, when we climbed one of the peaks of the Shala range, to a height of 2,019 m. we had to be particularly cautious because the rugged limestone cliffs here constituted the tribal border between Nikaj and Shala. A few nights earlier, the Nikaj had shot four Shala who had fallen asleep at a spring that was outside the confines of the safe trail. From the distance, we could hear the moaning and screaming of their relatives that lasted for several days. It sounded more like the lowing of wild animals than the crying of human beings. When the men had cried their fill and were hoarse, the women took up the repulsive refrain.

Theth in the Shala Valley

(Photo: Robert Elsie, May 2013).

Blood feuding is the worst scourge of Albania. Religion has been unable to moderate it at all. It demands 3,000 victims a year in all of Albania. In High Albania, a full 25% of annual deaths are the result of feuding. It would, however, be wrong to condemn the feuding entirely. In the final analysis, it is a reflection of a certain sense of justice or of legal protection in a country of total anarchy where there is no government authority. What makes the century-old custom particularly abhorrent, however, is the fact that it is often used simply as a pretext to get rid of rivals and to take possession of their property or their wives. The custom relies to a good extent upon false witness statements and there are many people who are willing to say whatever is needed, generally out of fear of their foes. In addition to this, the feuds affect not only the guilty parties as such, but their innocent male family members, right to the most distant relations. Since, in Albanian thinking, every victim must be avenged, the duty to take revenge passes on from father to son and has led to the eradication of whole families, except in cases where reconciliation was achieved from mutual exhaustion. One is not even safe in one’s own home. For this reason, houses are built of solid stone and have embrasures instead of windows. In many villages there are fortified blockhouses with numerous embrasures where the men sleep at night and can defend themselves if attacked.

Feuding has such an impact on the natives that not only families are affected. Whole villages and tribes can be caught up in the vendettas. For this reason, contacts between the tribes have been reduced to nothing. Farming is only possible in the immediately vicinity of a village and wherever there are landmarks, there is fighting. To protect themselves more effectively, many of the tribes or banners join forces for a time and conclude a besa or so-called blood friendship. Whenever a member of one of these banners is murdered, the whole tribe is obliged to take revenge by shooting and killing any member of the opposing tribe that they can get their hands on. Since there is no due process of law, many innocent people die instead of the guilty ones, and even foreigners are not completely safe. In cases of extreme animosity, it is regarded as a point of honour to murder guests because the tribe who hosts them is then forced to take revenge twice over.

On our journey the next morning to Sheher i Shoshit, our porters kept their fingers on the triggers of their revolvers. We could only hire them on condition that we took men from two different settlements, because a potential killer would then face revenge from two villages. We climbed 1,000 m. down the steep slope leading to the Kir Valley and returned to Shkodra in the company of an old woman because none of the men would take us, out of fear of blood feuds. We were relatively safe in her company because no honorable Albanian would ever attack a weak, defenceless and, to boot, unworthy woman, and her companions.

As with most savage and semi-savage peoples, the Albanians accord a subordinate role to their oppressed women. For all their troubles, they receive little thanks or affection. Their suffering begins the moment they get married. They are the pack-mules of the family because the whole family depends on them. Since men are restricted in their activities because of the blood feuding, whereas women are inviolable, it is that latter who must do most of the field work and must often hike for days over to the nearest town to exchange their miserly produce for the necessities of life. Nonetheless, they never forget to take their knitting or distaff with them. Even when they are burdened down with the goods they must carry, their hands are always busy.

[excerpt from: Streifzüge in Ober-Albanien, published in: Verhandlungen der Gesellschaft für Erdkunde, Berlin, 1897, vol. 24, p. 529-544. Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.]

TOP