| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

![]()

Henry Brailsford

1903

Henry N. Brailsford:

Macedonia: its Races and their Future - the AlbaniansHenry Noel Brailsford (1873-1958) was a British journalist who was quite well known in his time. The son of a Wesleyan Methodist preacher, he was born in Mirfield, Yorkshire, and educated in Edinburgh, Dundee and Glasgow in Scotland. Brailsford worked in the 1890s as foreign correspondent for the “Manchester Guardian”, in particular in France, Egypt and the Balkans, and later in London he wrote for the “Morning Leader”, the “Daily News” and “The Star”. In 1903, he and Edith Durham led a British relief mission to Macedonia. As a man of the left, Brailsford joined the Independent Labour Party in 1907 and in 1913-1914 he was a member of an international commission sent by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace to investigate the conduct of the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913, and co-authored its report. Of the numerous books he published in the first four decades of the twentieth century, he is remembered in particular for “Macedonia: its Races and their Future” (London 1906), which contains a long and perspicacious chapter on the Albanians. After a general introduction on the Albanian character, language, history, customs and religion, Brailsford describes at length the struggle for Albanian education in Korça and (given here) the situation of the Albanians in Kosova, also known at the time as Old Servia. The chapter concludes with some lucid observations on the future of the Albanians, as seen from his perspective in the year 1903.

Prizrend and the Reforms

If Koritza is the capital of Lower Albania and of the milder Tosks, with their quasi-Hellenic civilisation and their new and bloodless cult of letters, Prizrend is a centre of the wilder Gheg race; and when I visited it in June, 1903, it was all agog with the Albanian revolt against the imposition of the Austro-Russian reforms. A strategic railway, which seems to carry no freight but cannon, no passengers save soldiers or prisoners of war, leads through a narrow glen from Uskub to the little village dépôt of Ferizovitch — a place which won some celebrity a year or two ago by rising in revolt against its Turkish Mudir (sub-prefect), and driving him forth minus his ears. At Ferizovitch Albania begins. The outward sign that its frontier has been passed is to be seen in the tobacco-shops. The little booths stand open to the street, and lithe men in white caps — the true Albanian rarely wears a fez — sit cross-legged behind great heaps of contraband tobacco. They sell it openly, without disguise. There once were branches of the Turkish tobacco monopoly in Albania, but it proved so easy to murder their managers, and so difficult to check the trade in “free” tobacco, that they have long ceased to exist. Those fragrant heaps of native leaves are the scutcheon of Albanian anarchy, the symbol of the failure of the Turks to make, even in externals, the faintest impression upon this race of mountaineers. Between three and four years ago, in consequence of a murderous but fortunately unsuccessful attack on the Austrian consul in Prizrend, a few beginnings of ordered government were made in that town. The blood of the consuls is always the seed of civilisation in Turkey. In Ipek and in Djacova there is still literally no law and no court of justice. The civil code, more or less on the Napoleonic model, which Turkey possesses, is not in force in these towns. Such justice as is administered is dealt out by religious functionaries whose code is the Koran. In all that belongs to the civil side of politics, we are still in the heyday of Islam. The kadi administers the law as it was laid down by the Prophet, and his court observes the same maxims and the same ceremonies which prevailed when the Barmecides were Caliphs in Bagdad. It is still the world of the “Arabian Nights,” and here in Europe, within a day’s journey of the railway that leads to Vienna, we are in the East and the Middle Ages. Elsewhere in Albania — at Scutari, for example — even the law of the Koran is unrecognised. The only canon of justice is the antique code of the Albanian clans, which must be pretty much what it was when Achilles led his myrmidons to Troy. It deals chiefly with murder and its punishment, explains in what circumstances a man’s house must be burned to the ground, when the son must die for the sins of the father, and under what conditions a man must take to the hills and devote himself in pursuit of vengeance to a life of outlawry. The Turks, despairing of replacing this code by anything of their own, gave up the struggle, and actually printed a translation of a crude version of it in the official calendar of the Vilayet of Scutari, thus adopting it as the law of the land. The historian in search of ironies and anomalies could find no stranger contrast than this of Turks and Albanians — the one, an Asiatic race of Mongol blood and the most meagre intellectual endowment, yet possessed, thanks to Arabian influence, of a fairly humane and elaborate code of laws; the other, a European people of Aryan stock, boasting in part a certain nominal Christianity, gifted, quick, and intelligent, and in contact through the ages with Greek and Italian civilisations, yet content in the twentieth century with a set of institutions which have remained unaltered since the first days of the Aryan migration. A show, however, was being made of changing all this when we were in Prizrend. Two new judges had been sent to Scutari, a Jew and a Greek. Both had been duly murdered. Two more had arrived in Prizrend, a Servian renegade and a Jew, and they were awaiting events. Turkish officials in Albania pass their lives in awaiting events. They bring little furniture with them, and feel their way cautiously before they unpack more than the bare necessities of life. The Albanians have a short way of demanding the removal of obnoxious officials. They simply make an appearance en masse, rifle in hand, round the official residence, and in a few hours’ time a cavalcade is courteously escorting its late Governor towards the dull plains where tame men purchase their ready-made cigarettes from the licensed shops of the Turkish Regie.

Some years ago an unusually enterprising Turkish official compiled a work which describes itself as the Year-book of the Vilayet of Kossovo. It contains statistics of population, and taxation returns for every town and district of the province. It has long since grown obsolete, for as the years roll by, only the date on the cover is altered. There is one item, however, which has never grown antiquated. It relates to the districts of Djacova and Ipek, of which it is truthfully stated on a blank page that “no reliable statistics have yet been published.” The plain fact is that Djacova and Ipek pay no taxes, and furnish no recruits to the Turkish army. It seemed for a moment as though all this would be changed, and in 1903 there were smooth official prophets who supposed that after a sharp revolt Albania had been cowed and reformed. It was a time of turmoil. Even the railway was forbidden to Europeans, and it was by a ruse, over which it is prudent to throw a veil of obscurity, that I contrived, during a brief absence of Hilmi Pasha from Uskub, to penetrate to Prizrend. Natives shook their heads, and spoke of the journey as an impossible adventure. It was twelve months since a European had been there, and he had gone in the train of two consuls, with a squadron of cavalry to guard him.

I left Uskub with high expectations. What might one not discover in that mysterious region, as strange as Arabia, as distant as the Soudan? I was not disappointed. I witnessed two miracles. I saw Albania tranquil, and discovered an official Turkish version of passing events which was substantially true. For the moment Prizrend was like any other town in Turkish Europe. It was outwardly stolid and calm. The Albanians, who up till two months before had never crossed the road without slinging their rifles on their shoulders, were going about unarmed. In the town nothing reminded you that you were in a country where no stranger dare walk alone — unless, indeed, you happened to look behind as you passed down some narrow secret street and detected an Albanian in the act of solemnly spitting on the ground to express his indignation at your presence. There had really been “a sort of war” in Albania. A battle did really take place near Djacova. The Albanians were really more or less cowed, and for the moment they had accepted the “reforms.”

Three months before, when we in Europe suddenly realised that there was an Albanian question, because an unfortunate Russian consul had been murdered in Mitrovitza, there were something like two thousand Albanians in arms round the town, and the inconsiderable Turkish garrison was wondering upon which side it would be more prudent to fight. And then week by week the faithful ragged regiments from Asia Minor began to arrive. By May there were thirty battalions ready to move. It was no trivial operation. The Sultan did not risk his troops in small detachments. And when thirty battalions came to Prizrend there remained nothing for the clansmen to do. They returned prudently to their villages, and left their rifles at home. It was doubtless humiliating; for your Albanian regards his rifle as our forefathers regarded their swords; it is the badge of nobility, if not of manhood, and, moreover, in this climate it is rather more necessary than clothing. But, after all, in Prizrend there was no particular need to resist. The thirty battalions interfered with nobody, and nobody interfered with them. It is true that twenty men were arrested, but as only three of them were persons of importance the incident could hardly be represented as a casus belli. The thirty battalions rested in dignity, and presently they moved on to Djacova.

View of Gjakova

(Photo: Gabriel Jaray, 1913)

Djacova despises Prizrend. In Prizrend there are two European families, while the soil of Djacova is still clean. And accordingly Djacova decided to indulge in passive resistance. For five whole days the market was closed, which is in the East the deadliest act of defiance. The thirty battalions and their three Pashas sat chafing while the telegraph worked. The three Pashas were not unanimous — why else should they be there? In Turkish armies there are always three Pashas — one to propose, one to oppose, and one to telegraph to Constantinople. Day after day the thirty battalions lay idle. Day after day the shops were closed. And Constantinople cautioned diplomacy. There must be no violence, no inconsiderate urgency, for Albanians are not infidels. But at last the order came which permitted the three Pashas and the thirty battalions to require the Albanians of Djacova in the Sultan’s name to open their shops. On the sixth day the shops were duly opened, and in the Sultan’s name they displayed once more to the eye of day and His Majesty’s troops the excellent contraband tobacco for which the district is so justly famous. It was the beginning of the end. The Albanians in the hills treated the enforced opening of the shops as a declaration of war, and proceeded to take a cavalry patrol in an ambuscade. Something like thirty troopers were killed, and then at length the Turks acted in earnest. For one day there was fighting. The Albanians held positions in the hills, and the Turks assailed them with artillery. At the end of the day the Albanians still held their rocks, and each side had lost somewhere between eighty and one hundred men. Then came further days of inaction, during which the Turks contented themselves with destroying about ninety mediaeval towers or koules.

These koules play some considerable part in the feudal organisation of Albania. Only a rich chief can build a koule. Since he is rich he must have been unscrupulous, and since he is bold he becomes a leader. To destroy his tower is in some sense to sap his influence. Meantime, however, Turkish reinforcements were moving up from Ipek, and the Albanians ran the risk of being taken in flank. They were without commissariat or organisation, and their food and ammunition were all but exhausted. Day by day they dwindled away, and when at length the thirty battalions advanced, the hills were deserted. For that year there was no more fighting. At Mitrovitza, where some nine hundred tribesmen had attempted to rush the bridge against Turkish cannon, and again at Djacova the Albanians felt they had done enough for honour. They knew the Turks too well to take their threats of a permanent occupation and a regular administration in earnest. But in any event they lacked the organisation for a prolonged campaign. At the summons of their chiefs each man had marched to the rendezvous carrying as many cartridges as he could wear upon his person. When these had been exhausted there was nothing more to be done. The Albanians seem incapable of the long years of preparation which precede a Bulgarian revolt. They collect no war chest, and they amass no magazines of ammunition. Their risings accordingly are alarming but brief adventures, and if the Turks can survive until each man has shot away his beltful of cartridges, they may enjoy their triumph — until the following spring.

The Bridge of Mitrovica

(Photo: Gabriel Jaray, 1913)And so for a season the comedy of reforms went on. Under the personal supervision of Hilmi Pasha the blank pages in the calendar of the Vilayet of Kossovo were gradually filled in, and beautiful lists were prepared showing how much these wild districts ought to pay in cattle-taxes, and how many conscripts they should furnish to be the despair of Turkish officers. (1) The budget of the Vilayet showed how the blessings of civilisation had already been squandered with a lavish hand on these wild regions. Half-way on the road to Prizrend we met a Greek engineer. He was a civilised man who had studied in Vienna, and he gladly stopped to talk with us and tell his tale. He had been for six months in the Turkish service. He had been sent to Scutari to inspect the roads — a grim Turkish joke. It seems he was actually sent on a voyage of discovery to look for bridges, but although he was surrounded by a powerful Turkish escort, the Albanians forbade him to go on. Four months later he was transferred to Prizrend. He was told that in a week the road from Prizrend to the railway at Ferizovitch would be repaired, and he proceeded to inspect it. Ten per cent of the Macedonian revenues, so Hilmi Pasha had told me, had been set apart for the repair of the roads. Something had indeed been done. Two months before our visit the road was a species of torrent-bed which wandered among rocks and rivulets. After a careful inspection we were able to discover, over a space of several miles, murderous pegs driven into the centre of it at intervals of three hundred paces. These were the reforms. The hand of man had undoubtedly made its mark on the torrent-bed, and when oxen tripped over the pegs and wheels broke against them the natives thanked Europe for the boon. But as for the Greek engineer, he had seen enough. He was tired of waiting for next week. The money and the labour to repair the road were not forthcoming, and he was on his way to Uskub to tender his resignation. He seemed to me typical of all that the Turks had done in these Albanian regions to realise the reforms. They boasted that they had purged the gendarmerie of its worst characters. Its ranks were, in fact, recruited from among the more enterprising robbers of the country. A few of the more notorious had been dismissed. Already they had begun to return. In the course of a single stroll through Prizrend two gendarmes were pointed out to me, both of them notable murderers, who had been cashiered and then reinstated. For the rest, a very few Christians have been enrolled in the ranks. I am bound in fairness to say that some precautions had been taken to ensure their safety. They spent their day shut up in the police-office, lest the Albanians should see them; and when they returned to their homes at night, they were not allowed to take their rifles with them, as their Moslem comrades did. It was thought that the Albanians might feel less insulted if these Giaour policemen went about harmless and unarmed. That an infidel should carry a rifle and arrest one of the faithful would have been intolerable. And if, after all, the Albanians should fall upon the defenceless gendarmes as they returned to their homes, there would be a minimum of bloodshed. From a certain standpoint this refusal to arm the new recruits must be viewed as a humanitarian measure.

Returning through Uskub, nearly a year later, I learned (April, 1904) something of the sequel to this curious chapter of history. The first attempt to enforce taxation and conscription at the expense of the Ghegs of Djacova and the North had led once more to a rising, this time more extensive and more dangerous. Dibra also was up in arms, and had not the Turks displayed notable strategy in preventing the union of the contingents from that region with the rebels of Liuma and Djacova, they might have had to face a somewhat serious rebellion. As it was, a very considerable Turkish force under Shakir Pasha was surrounded near Djacova, and would have had no resource but capitulation had not Shemsi Pasha marched from Uskub at the head of a formidable army. The negotiations which followed ended in a substantial success for the Albanians. The Turks did not quite consent to renounce their rights to raise taxes and enrol conscripts in Upper Albania, but they did agree to postpone these obnoxious operations for two years — a term which is likely enough to prove an equivalent to the Greek Kalends. The Turks, of course, are compelled in deference to Austria and Russia, to continue to make a show of introducing reforms, and from time to time some Christian Servian gendarmes are enrolled. But it is tolerably certain that if these attempts should seem too serious or too persistent, the Albanians will rise once more.

It is a little difficult to explain the motives which have brought about these Albanian risings. When a Bulgarian takes a rifle in his hand, appeals to the sympathy of Europe, invokes the sanctity of the Berlin Treaty, and says that he wants liberty and autonomy, reforms and a constitution, we think that we know what he means. He uses the catchwords of Western Europe, and his attitude towards ourselves is deferential. But the Albanians have defied Europe. They began their campaign by murdering M. Sterbina, the Russian Consul at Mitrovitza. And their object seems to be to protest against reform. Certainly, if we look no further than the surface, their movement is not deserving of much sympathy. It seems to be confessedly reactionary, and Europe has some excuse if she supposes that they are more fanatical than the Turks themselves. Their leaders, too, are men of the old school, chiefs whom the average Christian of the Balkans describes without hesitation as “brigands.” It is true that some of them have risen to consideration through rapine. A brigand or a successful “rural guard” will often retire on the proceeds of his robberies, build himself a mediaeval keep, and terrorise the neighbourhood. His district becomes an Alsatia, a refuge for every desperate outlaw, and he concludes no treaties of extradition. The Turks make it their policy to humour him. The highwayman of yesterday is decorated to-day, and the path is open to uniforms and offices. He becomes a kingmaker in his little territory. At his complaint the prefect (Kaimakam) is dismissed, and if he makes common cause with a few of his fellow “chiefs” he may even hope to unseat a Vali. He is free to rob, free to murder, free to grow rich. No Christian dare complain against him, for the local officials are his creatures. If he has a behest to make, he need only send the bellman round the town to shout it to the people. When it was rumoured that a Russian consul was coming to Mitrovitza the chief Isa Bolétinaz sent his henchman publicly drumming through the streets with the cry, “I, Isa Bolétinaz, forbid any man of Mitrovitza to let his house to the Russian Consul, and if he does, it will be the worse for him.” But the better class of these men are hereditary chieftains of old families, who have won their martial reputation, not in brigandage, but by prowess in local feuds. Isa Bolétinaz, for example, spent six years “in the mountains” avenging the murder of a relative. In the course of a campaign of this sort an Albanian may play the brigand, in the sense that he lives upon the country; but his object is not so much plunder as revenge. The distinction may seem a subtle one. Certainly the men behind this movement — Suleiman Batusha and Isa Bolétinaz, for example — are the representatives of the old anarchical tradition. To some of them anarchy is a vested interest, to others it represents a sentiment of independence.

At bottom the Albanian movement is, like all Balkan movements, inspired by a nationalist ideal, and by a wish to obtain emancipation from Turkish rule, and if it wears an appearance of hostility to Europe that is only because Europe ignored Albania in the Berlin Treaty, and because she has made herself in practice the protectress of the Slavs, with whom the Albanians have a traditional feud. I have often tried, in conversation with Albanians, to obtain some clue to their attitude. The Ghegs have, as a rule, too little education to explain with any clearness what it really is they mean and want. The rising was an instinctive outburst. But if one can imagine a Gheg primitive enough to share the views of Bolétinaz and his tribesmen, and educated enough to state them clearly, it is somewhat in this way that he would explain the national attitude: “We Albanians,” he would say, “are the original and autochthonous race of the Balkans. The Slavs are conquerors and immigrants, who came but yesterday from Asia. As for the Bulgarians, they are a Mongol tribe which has no business in Europe. The Russians may call themselves Europeans, but when their consuls come here and lord it over us with their whips, we notice their little eyes and their high cheekbones, and we feel that they too are Tartars. The Servians, under their Tsar Dushan, conquered the country which they have the impudence to call ‘Old Servia.’ They settled there and drove us back for a season to our mountains. But little by little we have regained our own. ‘Old Servia’ is Albanian once more to-day, as it always was and always will be. It is true that a minority of Servians remains, protected by Russia. She has even sent up a handful of Russian monks from Mount Athos to hold the sacred Servian monastery of Detchani. Why is it that she defends our hereditary enemies? Because they are Slavs. These so-called ‘reforms’ are nothing but the device of a Panslavist conspiracy. Why does Russia confine her attention only to the Vilayet of Kossovo, while she does nothing for Jannina and for Scutari? Because there are Slavs in Kossovo. Why does she do nothing to help us with our schools and our language? Because we are not Slavs. These reforms are only intended to benefit the Slavs. Why, then, should we submit to them? Russia tells you that there ought to be Christians in the gendarmerie, and you imagine that we are fanatical because we oppose her. It is not a question between Moslem and Christian at all. There were hundreds of Catholic Albanians in our ranks when we fought at Mitrovitza and at Djacova. In point of fact, when Russia says that there ought to be Christians in the gendarmerie, she means Servian Christians. When the time came for enlisting Christian gendarmes, whom did the Russian consuls recommend? They got together all their own spies, their agents provocateurs, the most notorious instruments of the Slav propaganda, and forced the Turks to put them into uniforms and to give them rifles. Shall we allow these men to rule over us? As for Austria, we all know that her dream is to annex Albania, and she too is a Slav Power. Her consuls are never Germans. They are always Czechs or Croats or Poles. Our programme is Albania for the Albanians, and we do not intend to submit to any foreign domination, and certainly not to that of the Slavs. If the Turks cannot protect us against Panslavism, then we are quite prepared to fight the Turks. We have never accepted their yoke. We have preserved our customs, our language, and our local independence. But we have never paid taxes. We have fought as volunteers for the Sultan in every Turkish war — at Plevna as at Domokos — but we have never worn the Turkish uniform or accepted the slavery of the barracks. You profess to be the friends of the Cretans and the Bulgarians when they defend their freedom. Why do you wish to impose the Turkish yoke upon us? It is, I suppose, because we are not Slavs, or because so many of us are Moslems. That is your tolerance. No, we do not want reforms. We prefer liberty.”

My imaginary Albanian has said some things which are absurd and other things which are true. One must look behind words. It was not against reform that the Albanians rose, but against the tightening of Turkish control, and the more distant menace involved in the predominance of Austria and Russia. Europe did a monstrous thing when she entrusted the destinies of Macedonia to two interested Powers. Both Russia and Austria are partisans in the Macedonian chaos. For generations they have been engaged in propagandas of their own, furthering the interests of one race against another to secure their own position and prepare their future claims. It was absurd to suppose that they could play the rôle of impartial arbiters. The Albanians speak the truth when they insist that they are themselves, by virtue of their numbers, overwhelmingly the preponderant population of “Old Servia”; but just in so far as they show themselves incapable of respecting the claims of the Servian minority, they destroy their own natural right to govern.

Old Servia

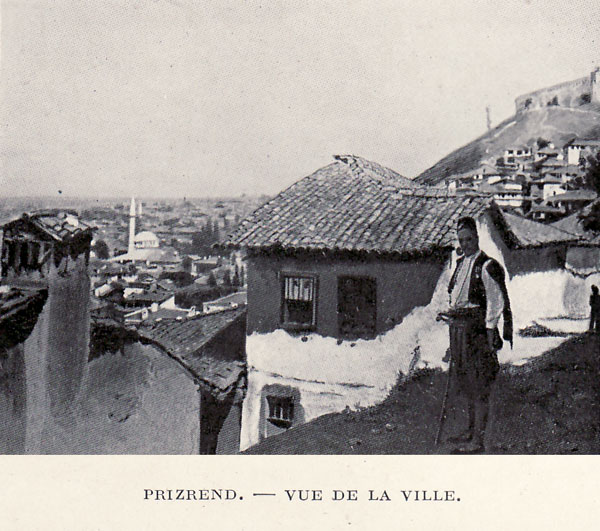

Prizrend stands on the low foothills of greater mountains. Its precipitous streets — with the brawling stream, the shady poplar groves, the cool rose gardens of dervish monasteries, the graceful mosques, and the secret, all but castellated houses that rarely expose a timid window to the outer world — rise towards the crumbling Turkish citadel on the hill. It is a hill of memories and vistas. At your feet lies the great plain of Kossovo, where the Servian Empire was shattered at the first shock of the invading Osmanlis. Far in the distance, to the north, is a dark range of mountains which is the frontier of New Servia. To the west, beyond Ipek, rises a vast Alpine wall of purple and white, and beyond it, too, is liberty. It is the frontier of Montenegro, where yet another branch of the Servian race has maintained itself and freedom. And behind lies the greater past. A narrow valley runs up to the mountains behind — on the right a green hill, on the left a bare cliff, and between them, in the distance, the blue peaks of the Schar Dagh. In the midst of the valley rises a sheer rock, and on its summit stands the old castle of Tsar Dushan. Here he lived and reigned, a Servian king amid a Servian people.

View of Prizren

(Photo: Gabriel Jaray, 1913)By some half-ironical convention this country that once was Dushan’s, within sight of the two free Servian lands, is known as “Old Servia.” It is the Servia that has been. I came expecting to find, as one finds elsewhere in Macedonia, a population by majority Christian, living under the rule of a Moslem minority. Two centuries ago that is what a European traveller would have found. Today the Serbs are a remnant which has dwindled by emigration, massacre, and forced conversion, to the rank of a mere third of the population. In the two districts of Prizrend and Ipek there are no more than 5,000 Servian householders, against 20,000 or 25,000 Albanian families. In all Old Servia there are not as many Servian families as there are Albanian families in Ipek and Prizrend alone. It was otherwise in the past. History tells of two great emigrations en masse from Old Servia. In 1680 the Servian Patriarch placed himself at the head of 100,000 of his people who had found Turkish rule intolerable, and with their flocks and herds, their cradles and ploughs, they wandered to Carlowitz in Hungary. Fifty years later a second human swarm, 30,000 strong, took the same road. It was the best and the most patriotic element of the Servian population that sought a refuge and a future in a Christian country, and practically every priest in the diocese followed the Patriarch to save his faith. The Servian population which remained, without leaders, teachers, or priests fell a natural victim to the Turks and the Albanians. Whole regions still Servian in blood and language embraced Islam at the point of the sword. The process went on in this forgotten country on the fringe of Europe even within the memory of the present generation. Thirty years ago the broad district of Gora, near Prizrend, was ravaged, decimated, and converted. Its inhabitants speak only Servian, and as far as they dare they maintain the tradition of their Christian past. They will go to the great monastery of the neighbourhood on its annual festival. The women will often beg a priest to pray for them or to give them holy water, and sometimes they will lie on the ground in the churchyard that the priest may step over them as he carries the Eucharist, in the hope of obtaining a silent blessing. If ever the Turk departs they will venture, no doubt, to return to the faith of their fathers.

Of the rest of the Christian Servian population of Old Servia, for every nine who remain, one has fled in despair to free Servia within recent years. The remainder, unarmed and unprotected, survive only by entering into a species of feudal relationship with some Albanian brave. The Albanian is euphemistically described as their “protector.” He lives on tolerably friendly terms with his Servian vassal. He is usually ready to shield him from other Albanians, and in return he demands endless blackmail in an infinite variety of forms. If the Servian has money he pays in money. There is a recognised etiquette even in brigandage. There arrives one fine day an emissary who carries a little parcel which he presents with much ceremony to the headman of the village. The parcel contains it may be ten, it may be twenty beans, with a cartridge tumbling amongst them. The beans represent silver dollars, and if gold is wanted their place is taken by ears of maize. The cartridge speaks for itself. It is death to refuse. But if the peasants are too poor to be blackmailed there are other methods of exaction. They can be compelled to do forced labour for an indefinite number of days. But even so the system is inefficient, and the protector fails at need. There are few Servian villages which are not robbed periodically of all their sheep and cattle — I could give names of typical cases if that would serve any purpose. For two or three years the village remains in a slough of abject poverty, and then by hard work purchases once more the beginnings of a herd, only in due course to lose it again. I tried to find out what the system of land tenure was. My questions, as a rule, met with a smile. The system of land tenure in this country, where the Koran and the rifle are the only law, is what the Albanian chief of the district chooses to make it. The Servian peasants, children of the soil, are tenants at will, exposed to every caprice of their domestic conquerors. Year by year the Albanian hill-men encroach upon the plain, and year by year the Servian peasants disappear before them. Hunger, want, and disease are the natural accompaniments of this daily oppression. One may gauge the poverty of this country from the fact that a day’s wage averages five or six metallics — say three English pence. Round Uskub it stands at tenpence, and Uskub is poor. But then if labour can be had for the asking by a master who has only to toy with a jewelled pistol in his belt the market price is inevitably low. The children grow up half nourished and scarcely clad, and the result, as the doctors of Prizrend told me, is an astonishing prevalence of lung diseases and anemia in this superb climate with its brisk mountain air, its pure water, and its generous sun. One is a little apt to think of the Albanian question as an interesting diplomatic problem, a fascinating ethnological puzzle. It struck me in a different light on market-day when the peasant women came toiling in, bent and wrinkled, with their babies on their backs, and round their meagre figures a collection of rags that barely satisfied the demands of modesty. We ask them what they have brought to sell. It may be half a dozen eggs, it may be a dozen. And the price? A halfpenny apiece, or less. And where did they come from? There were some who had come from a village ten and even fifteen miles away. To sell a few eggs for threepence these Servian women will walk a matter of twenty dangerous miles. It is their one chance of keeping alive. The threepence will buy a bag of Indian meal that will serve the family for a few days, eked out with onions and wild herbs. And by next market-day there will be a few more eggs to sell, if the saints are good — unless, indeed, some hungry, unpaid Turkish detachment should pass through the village and requisition the few hens that stand between the peasants and famine.

Those women, in their misery and nakedness, are the other side of the gay picture of Albanian chivalry. With all my memories of Bektashi tolerance and Arnaut patriotism, framed in a picture of marvellous mountain scenery — the white snows of the Schar Dagh, crisp and clean on the midsummer day when we crossed them, its cold, exhilarating air, its Alpine roses, its hillsides of gentians and forget-me-nots — I realise painfully that I have visited the most miserable corner of Europe.

The Future

Of the future of Albania it is difficult to write with any measure of comfort or conviction. This gifted and interesting race has awakened too late, and one fears that the crisis in its fortunes must come before it has had the leisure to prepare itself for freedom. It has won no recognition from diplomacy, and the young States which surround it have regarded it as their legitimate inheritance. Greece lays claim to Epirus, and Servia to the plain of Kossovo as far as the mountains which rise behind Prizrend, while Montenegro, the especial protégé of the Tsars, has also her ambitions. Carved up among these alien countries, Albania would go the way of Poland, and her dream of a national existence would have vanished almost before it had begun to inspire. Beyond these minor competitors stand Italy and Austria, each anxious to obtain a share, if not the whole. Indeed, the only hope that seems permissible is that among so many claimants, the easiest and the least dangerous solution may after all prove to be an autonomy upon national lines.

The claim of Greece to Epirus rests on a hoary confusion. The Christian minority of Lower Albania may be Orthodox in religion, but it is Greek neither in language nor in race. And yet one must admit that a Greek occupation of Epirus would not be an unmixed evil. There is a large population which is still Greek in sympathy, and Greek in such culture as it possesses. A great number of the Moslems would undoubtedly return under any Christian rule to the faith of their fathers. In two generations Epirus would be as much Greek as Attica is to-day. For the greater part of the population of Northern Greece is undoubtedly Albanian in origin. The addition of so large an Albanian element to the Greek kingdom would, on the other hand, dilute its Hellenic character still further, and possibly the Albanians would be strong enough to force the Greeks into some reluctant show of tolerance, and even into a tardy recognition of their language. But the chief objection to this solution is, to my mind, that it would rob Albania of its most progressive and enlightened element. An Albania which included Epirus would already contain a considerable population on a relatively high level of civilisation, which might be trusted to leaven the whole mass. Deprived of the Epirotes, Albania would be a little principality of savages whose progress towards order and letters would be intolerably slow.

The case for a Servian annexation in the North is at once stronger and weaker. While there is no considerable Greek population in Southern Albania, there is a large Servian element in the North. On the other hand, there is a traditional feud between Servians and Albanians which would render the peaceable administration of the country under a Servian hegemony more than difficult. The Greek genius exerts a certain ascendancy and fascination over the Southern Albanians. It has been a civilising influence. It can quote a long and often friendly intercourse, and to bridge the connection there is already a large population of Hellenised Albanians established in the present Greek kingdom — a population as loyal and as advanced as any in the Greek world, and one, moreover, which has contributed more than its fair share to the laurels of modern Hellenism. With the Serbs it is quite otherwise. They have never played the part of civilisers in Northern Albania. So far from regarding them as his superiors in culture the Albanian has learned to despise and to exploit them as his villeins. A Greek dominion in Southern Albania would seem comparatively natural, and would imply no violent reversal of traditional habits of thought. But Servian rule in the North would imply a social as well as a political revolution. The Servian minority already settled about Prizrend and the plain of Kossovo would tend to become a party of ascendancy, and its novel and irritating pretensions would seem to the Albanians peculiarly degrading and offensive. These local Serbs have hitherto held their lives and their property on a species of feudal tenure from their Albanian overlords. That they should become prefects and deputies protected from Belgrade would be an inversion of every custom and an outrage on every prejudice. Moreover, the Servians of Servia have not succeed in conciliating their local Albanians as the Greeks of Greece have done. When the Southern limits of the Servian kingdom were enlarged after the Treaty of Berlin, the greater number of these Albanians were driven across the frontier, and in the process there were wholesale evictions and uncompensated confiscations of estates. Both races are convinced that the country is theirs by right, and it is difficult to imagine any satisfactory compromise between them.

The Albanians can boast the advantage of actual possession. They form the majority of the population almost everywhere between the Servian frontier and the mountains behind Prizrend. They are also the aboriginal population, and if one goes far enough back, they can regard the Servians, with perfect justice, as intruders and usurpers. On the other hand, Kossovo was the metropolis and the cradle of the Servian Empire. In Prizrend and in Uskub the great Dushan had his capitals. At the monastery of Detchani, near Ipek, the Servian kings were crowned, and round it gathers all that is most sacred in the legendary memories of an imaginative race. Nor does their historical claim end with the overthrow of Dushan’s Empire by the Turkish invaders on the field of Kossovo. Up till the close of the seventeenth century Ipek was still the Servian centre, and its Patriarch preserved the identity of the national Church. It may be true that the Albanians who have colonised “Old Servia” during the past two hundred years were only resuming possession of land which was theirs before the Servian Empire existed. But the methods of their settlement have been those of rapine and usurpation. If they succeeded to derelict and unoccupied lands, it was their ferocity which had rendered them untenanted. Each race has a claim so ancient and legitimate, and their recent relations are so complicated with injustice and the resentment it brings with it, that neither could live happily under the dominion of the other. The Serbs could not establish themselves without serious fighting and long years of coercion, while the Albanians would certainly use authority to complete the exile of the Servian race. The Servians lack the force to make their rule respected; the Albanians lack the civilisation to make their domination tolerable.

(1) The name by which the Albanians describe their Turkish officers is quite unprintable; suffice it to say that it breathes a withering contempt. The result is that an Albanian regiment in time of war or revolution does precisely as it pleases. I have heard a European witness describe how the Albanian conscripts employed in Adrianople during the late rebellion instead of marching, rode about in commandeered landaus.

[Extract from: H. N. Brailsford, Macedonia: its Races and their Future (London: Methuen & Co. 1906, p. 262-280.]

TOP