| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1907

Theodor Ippen:

The Bazaar of Shkodra

Theodor Ippen in Albanian dress

(Photo: Marubbi 1900).

Austro-Hungarian scholar and diplomat, Theodor Ippen (1861-1935), was born to a (baptized) Jewish family in Vienna and studied at the consular academy there. In 1884, he served at the Austro-Hungarian consulate in Shkodra, where, in 1887, he was appointed vice-consul. In 1895, he was appointed consul in Shkodra. From 1905, he served in Athens and, from 1909, in London, where he took part in the Conference of Ambassadors as the representative of Austria-Hungary. Theodor Ippen was particularly knowledgeable about the early history and ethnography of northern Albania. Among his major works are: “Novibazar und Kossovo: das alte Rascien” (Novi Pazar and Kosovo: Ancient Rascia), Vienna 1892; “Stare crkvene ruševine u Albaniji” (Old Church Ruins in Albania), Sarajevo 1898; “Skutari und die nordalbanische Küstenebene” (Shkodra and the Northern Albanian Coastal Plain), Sarajevo 1907; and “Die Gebirge des nordwestlichen Albaniens” (The Mountains of Northwestern Albania), Vienna 1908. The following description of the old bazaar of Shkodra – now long gone – stems from the first years of the twentieth century.

The division between the commercial and residential parts of the town is more pronounced here than in any other oriental city. The two are separated by open fields and olive groves. In the morning, almost all the male inhabitants of Shkodra file out from the new town in long lines for the bazaar and spend the whole day there. Before sunset they return to their families – the poorer people on foot carrying little rucksacks with the food they purchased, and the wealthy merchants on horseback and, more recently, in carriages, which were unknown here until recently as a method of transportation.

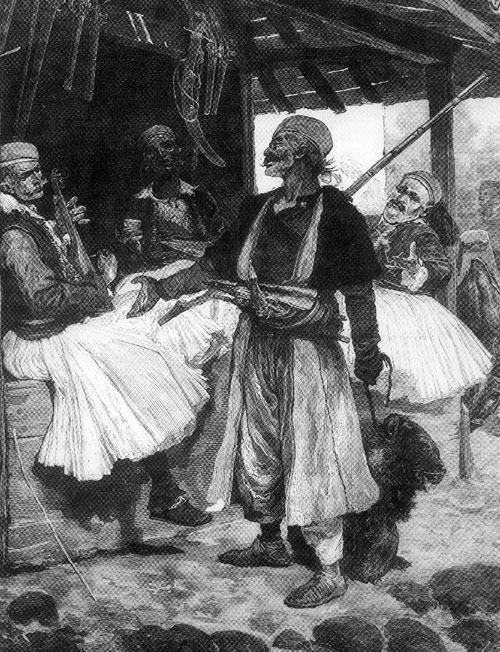

Richard Caton Woodville,

The Bazaar of Shkodra,

engraving, 1880.

The bazaar nestles at the foot of the fortress and extends down to the bridge in a long and narrow formation. Through it run one main thoroughfare and numerous side streets that branch out into a network of alleys and little squares. It is a labyrinth for the foreign visitor, in which it is all the more difficult to walk and find ones way because of the terrible, slippery cobblestones, gutters, protruding posts and the uniformity of the buildings. The latter consist of several hundred little stone shops, being either one-storey or two-stories high. The fronts on the ground floor lie open all day in their entire width and are locked up at closing time with the help of several wooden beams piled on one another. In these premises, that are used both as stores and as workshops, sit handicraftsmen and merchants waiting patiently for customers. Some of the buyers enter the shops to make their purchases, but most of them just stand out on the street in front of them.

As to larger buildings, the bazaar of Shkodra has a bezestan dating from the Bushati period, which is a typically oriental market hall for particularly valuable goods. Located around it are the shops and offices of the wealthier merchants. Also in the bazaar there is a medresa, a theological school, which consists of several fine but rather neglected kiosks and a separate library building. Of the seven small mosques located here, one of them has the curious name of Tu selvia e hunkjarit (At the Sultan’s Cypress) because of the topped cypress tree in its courtyard. Above the bazaar rises the dome of the mausoleum of Baba Mustapha, a local saint, who also has a strange name. He is popularly known as Zoja pazarit (The Lady of the Bazaar). The word zoja is used by the Catholics to refer to the Madonna and one can thus imagine that there was once a church dedicated to St Mary here and that the church name was later given to the mausoleum.

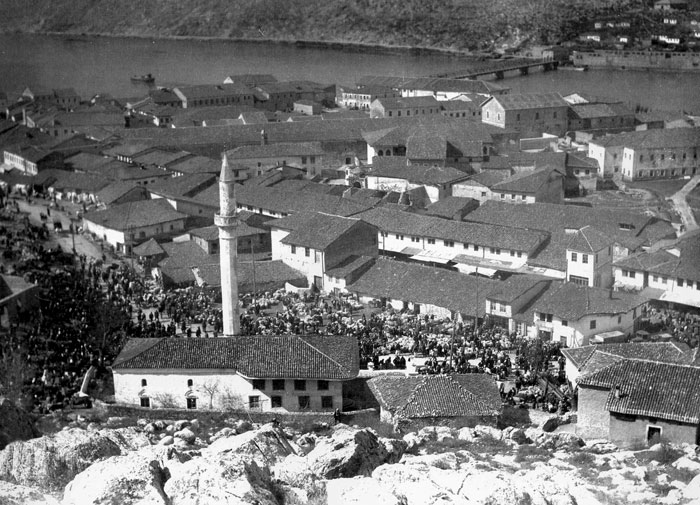

View of the bazaar of Shkodra

(Photo: Marubbi, ca. 1895-1910).

As in other oriental bazaars, though perhaps not as strictly, the various handicrafts are separated and located in specific streets and alleys, one after the other: potters, carpenters, blacksmiths, saddlers, and coat makers. In some back alleys one can find coppersmiths, tailors, gold embroiderers, silversmiths, etc. all together. However, the bazaar is no longer the hive of activity it was around 1860. The prosperity of Shkodra slumped with the decline in its importance as a major trading centre for the Balkan Peninsula. In the first half of the 19th century, the town imported many European goods for the whole western half of the peninsula. Its merchants maintained warehouses in Prizren, Üsküb [Skopje] and Monastir [Bitola] and attended the great fairs in Serres and Philippopel [Plovdiv]. Almost all the silk of Roumelia was exported through Shkodra and, in the other direction, silken products were imported here for markets throughout Roumelia, Serbia, Bosnia and Dalmatia. However, one should not conclude from the great fortunes that a number of Catholic merchants amassed here – Muslims were only peripherally involved in commerce – that the people of Shkodra were great traders with a keen sense of commercial enterprise. The people of Shkodra were more usually small retail merchants involved in small-scale businesses. Their commerce has been gradually stifled by the rise of Adrianople [Edirne] and Salonica [Thessalonike], by the introduction of steamers on the Danube up to Belgrade and later by the railway line between Salonica and Mitrovica. However, there were equally local administrative reasons for their downfall.

Alley in the bazaar of Shkodra

(Photo: Alexandre Degrand, 1890s).

The poverty of the population was so overwhelming that, even before the tragic earthquake of 1905, many Catholics left the town. They emigrated to Montenegro, southern Dalmatia, Hercegovina and Bosnia where they worked as shopkeepers and innkeepers. They own all the shops and cafes in Virpazar, Rijeka and Cetinje. The Muslims do not engage in these professions and are thus all the poorer.

Of the few attractions that Shkodra has to offer, the bazaar is probably the main one. A walk through the alley of the silversmiths is fascinating. With the primitive tools at their disposal, they produce fine filigree work with tasteful patterns on tobacco tins, buttons, brooches, earrings and bracelets, etc. Also produced are handled cups and sheathes for knifes and swords. In earlier days, silver-inlaid pistols and beautifully ornamented cartridge boxes from Shkodra enjoyed a great reputation throughout the Balkan Peninsula. Since the introduction of more modern weapons, it is only the shafts of the pistols that are adorned with filigree, into which coral and colourful gems are implanted.

The decline in handicrafts is more evident in the alley of the gold and silver embroiders. They used to be extremely busy because the costumes of rich Muslim women and the vests and jackets of the men were so covered in gold embroidery that very little of the original cloth was visible. Now there are only a few master craftsmen left.

Some workshops produce belts for the highland women. There are two kinds of belts. One is made of leather and is covered in shiny steel clips. The other consists of a line of brass plates and ornaments, including other paraphernalia, similar in form to objects that have been found in prehistoric graves in this country.

Library

in the bazaar quarter of Shkodra

(Photo: Theodor Ippen, 1907).

A particularity of Albania is that some handicrafts are only exercised in certain regions or towns, or only by a certain religious community. Silversmiths, for instance, are all Catholics from Gjakova. Potters come from Kavaja. Bakers are usually Bulgarians from Struga on Lake Ohrid. No one in Shkodra would dare to compete with them. Coppersmiths and tinsmiths who plate kitchenware and copper utensils are immigrant Serbs and Vlachs. Saddlers and butchers are always Muslims. Most of the goldsmiths and silversmiths are of this faith as well. The bazaar of Shkodra used to have a monopoly over silk production and tanning. These handicrafts have declined, too. The oldest part of town called Tabaki, at the foot of the fortress, is named after the tanning profession. Here, “n’ vakt vezirit” (at the time of the viziers), one found one tanner after the other who produced Moroccan leather goods that were much sought after and well paid for. At present, all that is left are the huge stone vats, many of them broken, in the gardens are Tabaki, that were once used to tan hides.

Like Istanbul, the bazaar of Shkodra has its own bit-pazar (lit. flea market). It is not without interest to visit it because the women here have home-spun textiles, clothes and embroidery on sale here for the highest bidder. There is another small triangular square, too, where the women, all huddled together and veiled in white, and with their fingertips dyed red with henna according to Muslim custom, offer home-made goods.

It is best to visit the bazaar on a Wednesday as this is market day. Men and women flood in from all the lowland villages and from the highlands as well to buy and sell their goods and produce. Many others just come for the entertainment, to meet friends and exchange information. The main thoroughfare teems with people and carts moving slowly down the road.

The bezistan of the bazaar of Shkodra

(Photo: Kel Marubbi, 1910-1915).

The clothing of the men, all dressed in white, loden garments finely adorned with black braids does not offer much variation. The minor differences in cut and embroidery that are the particularities of the various regions are only visible to the trained eye. Particularly noticeable are the men of Mirdita in their long creased robes falling to their ankles. The men from all the other regions wear short Spencer jackets. Women’s clothes, on the other hand, evince a wide range of styles and colours. Peasant women from the mountains east of Lake Shkodra wear a bell-shaped skirt in a red and black pattern that extends almost to their ankles. It is richly decorated with silver chains. On their heads they wear colourful silken kerchiefs or white veils. Less outlandish but quite pleasant are the clothes of the women who stem from the valleys of Shala and Pult. They wear culottes that come together skittishly at the back, fastened with a metal clasp. Peasant women from the lowlands prefer a short, black pleated dress. The poor women of Mirdita who are starving and overworked, dress in loosely hanging linen garments. Not all of the Muslim villages in the surroundings are strict about the use of the veil. Some of them let their women go to market unveiled. The peasant women from Anamali and the Drin, on the other hand, are so enveloped in white cloth that you can only see their eyes. On top of this, they are also covered over in large white sheets.

On the other days of the week, the bazaar is a rather quiet and lonely place. The shopkeepers and handicraftsmen pay one another visits, drink coffee, smoke cigarettes and talk politics all day. If anything happens that makes them nervous, they swiftly set aside their yardsticks and scales and take out their rifles and revolvers. The leaders give orders to shut all the shops and no one dares contradict them because these orders are always a prelude to violence. Closing down the bazaar is also a method used by the people of Shkodra to protest against the government. It is a sort of general strike used to express their feeling that the situation is not secure enough for them to work in peace and quiet.

[excerpt from Theodor A. Ippen: Skutari und die nordalbanische Küstenebene (Sarajevo 1907), p. 27-32. Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.]

TOP