1907

Marko Miljanov:

The Life and Customs of the Albanians

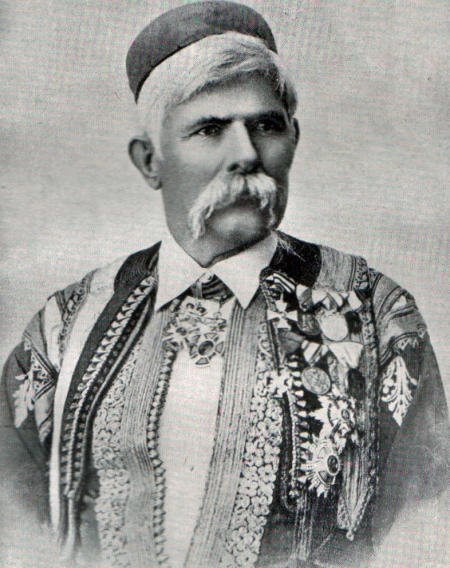

Marko Miljanov (1833-1901), known in Albanian as Mark Milani, was a Montenegrin warrior (chief of the Kuči tribe), a noted military figure and a writer. His father was an Orthodox Slav and his mother a Catholic Albanian. He served Prince Danilo I of Montenegro and led his forces against the Ottoman Empire (including Albania) in the wars of 1861-1862 and 1876-1878. After a disagreement with Prince Nikola in 1882, Miljanov withdrew from public life and, though illiterate up to then, decided to learn to read and write. His posthumously published book, ‘Život i običaji Arbanasa’ (The Life and Customs of the Albanians), Belgrade 1907, from which the following excerpts are taken, is without literary pretension but is fascinating for the views he offers about the neighbouring highland tribes of Albania, with which his Montenegrin tribe had much in common. Introduction Our people do not really know the customs of the Albanians though they are our neighbours. Some people think they are more coarse and savage than other peoples, but I do not think so. I do not intend to speak about their antiquity because this would go beyond the scope of this work. The ancient Greeks and Romans must have written about them because the Albanian people no doubt take their origin from those regions. I intend to explain a bit about their customs, which I admire. These are the customs of a simple people, a people bereft of scientific knowledge and legal concepts. They are better than other people who have had such knowledge and have known better how to preserve their identity. Over the centuries, foreign rulers and occupiers have forced them to change their customs and have brought them under their sway, or dealt with them as they did with other peoples who took over foreign customs in the course of time and changed not only themselves, but everything they inherited over the centuries. Despite foreign occupation, the Albanians have remained true to themselves, unchanged and unbroken, with their ancient language and the rifles with which they were born. This makes us think that this people has something stronger and more stable about them than other peoples have. Otherwise it is difficult to explain how this people did not permit any change to themselves over the centuries, after all the foreign occupations they suffered and after all the transformations that have taken place. However, as I said, I do not want and am unable to deal with their origins. I will rather expound upon the customs of the modern Albanians, which are probably only a small portion of the customs they had in ancient times. If the customs dealt with in this book are few, let them nonetheless serve as an example of the noblest customs of this people. Blood Brothers and Guests to Whom You Offer Protection First of all, I will begin by speaking about the custom of blood brothers. When Albanians become blood brothers, they say: “Blood brothers are closer than brothers because brothers come from their mothers and fathers, whereas blood brothers come from God himself, and because God is above everything else, the closer you are to God, the closer you are to mankind.” The Albanians say: “If someone should happen to kill your brother and your blood brother, you must first avenge the death of your blood brother and then that of your brother. If a second or third brother, or as many brothers as you have, should be killed by the murderer of your blood brother, you must not avenge any of the deaths until you have avenged that of your blood brother. Only after this may you take revenge for your murdered brothers.” Orthodox church with the grave of Marko Miljanov on a hilltop at Medun, Montenegro (photo: Robert Elsie, March 2014). In the same manner, you must take revenge for friends and guests to whom you offer protection as would for your blood brother, not only for friends whom others consider to be as such. Anyone who mentions your name at the moment of a killing is considered a protected guest. Here is an example. It often happens in Turkey in various ways when one sturdy man comes upon another, but it can also happen in other countries where there are no laws. It happens when one or more men encounter someone they are afraid of. They immediately mention someone’s name of whom they have heard that he is a good man. For example, if someone turns up on the road and threatens them, they say: “We are under the protection of someone or other,” and mention his name. At that moment, no one is allowed to kill them or to take anything from them. By means of such a statement, they can go wherever they want. If some evil should befall them, the person whose name was mentioned or his brothers are obliged to take revenge. He must not put his rifle down until revenge has been taken. He must go where he must, and kill whom he must. It has happened in many parts of Albania that a blood feud lasts for a hundred years and that whole generations are wiped out by killing one another, and this in particular because there are men among them who insist on killing more than they should, instead of taking blood one for one. This occurs most often in cases where a blood brother or a guest, who has evoked a name for protection, has been killed. Among these families there are some that are entirely bereft of male members, so that revenge cannot be taken on them. To carry out the revenge, they must kill a protected guest or blood brother. In cases where there are no guests or blood brothers left, it is the women, widows or orphaned children who take revenge, even if they have to pay money to get someone to do it for them. When they have collected enough money, they begin to kill the murderers who are still alive, i.e. the men whom their husbands had not been able to slay before they died. Such women pay up to their last cent to restore their honour by the revenge killing. There is no greater misfortune than someone who cannot take revenge for a devastated family and an extinguished lineage. As such, this esteemed form of revenge and friendship have been the companions and guardians of many lives on Albanian territory when there were no courts of law because Turkish courts were never friends of that people. What is worse, the Turkish courts knew full well about the crimes committed among the Albanians and, far from trying to prevent them, they encouraged them to be committed more and more. The courts could not carry out justice according to Sharia law because the people refused to have anything to do with the sultan’s courts. The Turkish pashas did not work to eradicate this evil. They did their best to ensure that the evil spread around the country as much as possible. There were two reasons that led the pashas to act in this way. Firstly, they wanted the energy of the Albanians to be sapped by constant fighting amongst themselves, so that they would be weakened. They wanted the evil of self-justice to go to the extreme until the persons in question were handed over to the courts, their heads bowed and their rifles thrown to the ground. Some of the Turkish pashas wanted thereby to convince the sultan that Albania could not be ruled in any other way, that is, if they did not incite the Albanians to wear themselves down until they were exhausted. The other interest of the Turkish pashas was that the court system not function in Albania. They preferred to see the Albanians oppose and fight one another so that they would have to pay more and more fines (even though fines could not really be collected in the territories where the conflicts took place). In many areas, this strategy succeeded because, throughout the region, there were enough weakened households, villages and tribes who finally preferred to go to court and pay the fine rather than be killed. However, I intend here to speak of the customs of the Albanians and not of Turkish courts. Vendetta There is a tale about Albanian blood- feuding from ancient times. It is as follows. When someone’s brother or relative is killed, they take blood from the body of the dead man and put it in a glass where they leave it. Revenge is not taken for as long as the blood remains coagulated. But when the blood seethes and spills over the glass, it is a sign that the time has come for revenge to be taken. The blood shows that the time is right and that the murderer has no way out but to pay the price, for fate itself calls for revenge. Among the many events of this kind, I would like to mention only one example of revenge being taken when foaming blood spilled over a glass. This is what happened. A group of armed Kastrati men attacked the herds and shepherds of Zatrepčani [Triepshi] at Bardanje [Bardhanje] near the Cijevna [Cem] River. The attack took place at dawn, when daylight emerged from the night. This event happened many years ago, and yet the Kastrati and Triepshi have not been reconciled up to the present day. But I do not intend to recall all the misfortunes that took place between them over the last hundred years, and I am not sure whether this attack was the actual origin of the conflict and all the fighting between them. What I do know is that the blood in the glass seethed and gave rise to a feud, not because of the death of a friend or a blood brother, but because of a child. This is what happened. During the attack, they stole the animals and slew the shepherds. But there was a little, eight-year-old boy there called Brunči [Brunçi], who was tending his goats, too. They realised that it was not proper for them to kill him because he was too young to bear arms (only a man who himself is able to kill, may be killed). The men decided to leave the boy alone, but when the lad saw his goats on the move, he ran after them and no one noticed him. He journeyed with the herd all night long. At dawn, the attackers noticed him and asked him: “Who are you?” “I am the son of Mark Petrov [Mark Pjetri],” replied the lad. “But where do you think you are going?” “I am looking after my goats.” “But we are not from here, poor boy, and we have taken all of the goats. However, we will give you one goat back. Take it with you and go home.” Little Brunçi took one goat, swung it around his neck and departed peacefully, passing by all the armed warriors of Kastrati. They watched the little boy as he happily drove his goat home. He was a good-looking lad and they watched him fondly, not like the killers they were who, but a few hours earlier, had slaughtered and pillaged everything they could find. But among the attacking force there was a fellow called Cuc Caka, a well-known fighter who, like a wild beast, was watching over the men. When he came upon the little boy with his goat, he stopped him and asked him: “Who are you?” “I am the son of Mark Pjetri,” replied the lad. The warrior drew his sabre from his belt and brandished it in front of the boy. “I am going to slice your head off.” The boy showed no fear and replied bravely: “You wouldn’t dare!” “I wouldn’t dare because of whom?” “Because of my brother, Pranlja [Prela].” Hearing this response, the warrior went berserk and, in one fell swoop, he sliced off the head of little Brunçi. All the other warriors spit and cursed him for the crime he committed against a little boy who had not yet reached the age to bear arms and go to war. When Mark, the father of little Brunçi, found the headless body of his son, he gathered what he could of the boy’s blood and put it in a glass. There it remained for several years until, one day, it began to seethe and foam, and spilled over the glass. When he saw the blood seething, Mark grabbed his sabre and went out to the threshing floor above his home. Brandishing his sabre, he ran back and forth across it. The wives of his three sons, who were fetching wood, laughed at him when they saw him running around on the threshing floor and said to one another on their way home: “Father has gone crazy!” Mark returned to his house and informed his sons that little Brunçi’s blood had begun to seethe, and that it was time to take revenge. “I am an old man now and can no longer use my sabre. I realised on the threshing floor now that I am unable to carry the deed out. But you are still young and unskilled. You don’t know the roads of Kastrati, yet I think you could easily take revenge without any great loss of life. From the foaming blood, it is clear that the time has come for the murderer to pay for his crime.” On hearing the words of the old man, the sons’ wives were ashamed that they had laughed at him. The sons replied to him, saying: “Since we do not know the roads and you are not able to carry out the deed, we will take you and carry you wherever you want to go so that you can tell us what to do. You just tell us where you want to go. Once you have told us what to do, we will bring you home and then go out and find that Cuc Caka, and take revenge for the death of little Brunçi.” As such, the three sons, Prela, Dreško [Dreshk] and Đon [Gjon], carried old Mark up into the mountains of Kastrati, to a high peak from where they could see everything they needed to see so that he could give them instructions. There was a cavern nearby with two entrances and in it were thirty shepherds and over one thousand head of livestock, small and large. When they got back home, they asked Mark about everything they had seen. He told them the following: “The three of you alone will not be able to overcome Cuc and the thirty shepherds in the cavern. You must go first to Lal Drekalov [Lalë Drekali] who will give you three hundred Kuči warriors to attack and take the cavern. Leave me right here. I will not move from the spot until I hear that you have slain Cuc and all of his men and cut them to pieces. Just bring me some bread and water so that I do not die of hunger or thirst while awaiting your return.” The three brothers set off and returned eight days later with the three hundred men of Kuči. They then asked Mark how they should attack the cavern, and he replied: “The cavern has two entrances, a large one and a small one. At the large entrance you will find the thirty shepherds, and at the small entrance you will find Cuc and his two companions. Therefore, the two strongest of you must attack the small entrance. When you kill Cuc Caka, his two companions will be confused and frightened and will run towards the large entrance. At that moment, the three hundred of you must attack.” They then said to old Mark: “We do not know which ones of us are strong enough to attack the small entrance.” Mark responded: “Come over here and I will tell you which of you are the strongest.” He began to poke his fingers in their bellies and after he had poked at all of them, he said to his son, Prela: “You are the strongest. You take over the small entrance.” He then said to another Triepshi warrior whose belly he had poked: “You, too, are strong enough for the small entrance.” And so, all of them went off to where they were told. Prela approached the small entrance when he got to the cavern. There he espied Cuc and the two other men who were lying in the cavern singing. The closer he got, the clearer their voices became. Prela and his companion listened to what they were singing. The song ended with these words: “Do not slay me, Prela Marko, By the Lord and by Saint John, no!” At that moment, Prela attacked, shouting: “Saint John will not help you this time, just as he did not help our little Brunçi to escape from you and your sabre when you slew him.” The other two men ran towards the large entrance but they were all killed. The livestock was seized and taken back to Kuči, and old Mark received them with great satisfaction, not only for the booty and the thirty men of Kastrati who were slain, but for the death of Cuc and for the capture of his sabre that was very famous by that time. This was the sabre he had used to slay little Brunçi and it was now safely in the belt of his son Prela. Revenge had thus been taken. The booty was distributed and the sabre of Cuc was handed over to old Mark, who kept it in memory of the deed. Hospitality I spoke above of blood brothers and of taking revenge for the death of a guest under protection. Now, let us take a look at hospitality, for which the Albanians have great respect. Should you have passed by one of their houses and not gone in so as not to cause expenses for the house owner, you have gravely insulted him. If you enter his house, you are paying him great honour because you have shown that you preferred his person and his house over everyone else. If the house is poor and they have nothing to offer guests, they will go out and get what is missing and will never ask for compensation for their expenses. What the house owner desires most is that his guest have everything he wants. Only then is he happy that he has been able to welcome a guest properly, because he considers it a matter of honour. The Albanians are never wont to say to a visitor: “I cannot lodge you for the night because I have no food to offer you for dinner.” Country lane in Triepshi (Zatrijebač) tribal territory, Montenegro (photo: Robert Elsie, March 2014). Their houses are open to all whether or not they have anything to offer to their guests. Later on, I will tell of someone who was not able to feed the guests who arrived at his house. I will continue on this subject because there are many peoples who are accustomed to welcoming guests into their homes even though they are very poor. Like the Albanians, there are prosperous peoples who open their homes to travellers and the needy, to guests and friends. Everyone gets more than enough to eat without paying anything. But it is particularly among the Albanians and in Rumelia that they pay special attention to hospitality, quite differently from in other countries. This is how the various tribes of this people act who are not well off and live in poverty. Even if they have no hearth and are not able to accommodate all the travellers, they still treat them as their guests for as long as they are travelling in their territory and until they cross the border into the territory of another tribe which, in turn, will then take the traveller in. They take great care of their guests and ensure that no one is left out in the cold. They also give them bread and water for as long as they are in their tribal territory. Wherever there are families who are not able to take care of their guests, the whole village pitches in and, together, build a hut for the guests in the most beautiful location they can find. This building is called the odaja musafirska [Alb. oda e mysafirëve] (the guestroom). It has rooms for the people, and stables for their horses or other animals for which there is always hay and fodder. The guests receive bread and water and get a place by the fire. In communities that organise such guesthouses, certain families are appointed, one after the other, to look after the oda e mysafirëve to ensure that nothing important is missing. Anyone can go and stay there as if he were in his own home. If his horse is bearing a heavy load, they remove the baggage and store it for the guest. They then take the horse off to the stables and, if there is no hay, they go to a nearby mill and get the animal enough to eat. The guest himself goes into the guesthouse, finds the dishes he needs and makes his own coffee because it can happened during the day that no one is there and if the guest arrives early, there may be no one to serve him. It is only in the evening that someone is obliged to be present and serve the guests. People would laugh at anyone who would not serve himself and feed his horse, but rather wait around for someone to serve him. About such people, they say: “He must be from one of those countries where there are no guests or hearths.” On the other hand, when they see someone serving himself and using the household equipment as if it were his own, even though he has never been in that house and does not know anyone there, they look at him with great satisfaction and are happy that he is making himself at home without hesitation, as if he were in his own house. They enjoy inviting such people over to visit their homes and families. Should some nitwit who does not know the customs, ask: “May I spend the night here at your home?” he has in fact insulted his hosts and they may quite likely react by saying: “Get out of here, go to hell. You cannot be our guest because you know nothing of our customs. How dare you even think that our home might be closed to visitors?” In such cases, not only the family in question will feel offended, but the whole village and anyone else who has opened his home to visitors. Such questions are degrading for them. He should know that their homes are open to anyone and everyone who knocks at the door. It is only the huts of dogs that do not open to visitors, whereas the house of a highlander and the hearts of all brave men are open for anyone who comes by. They think that anyone who does not know this and has to ask, does not merit their hospitality. The Albanians praise all things good and beautiful, whereas they cast bad things from them, as do other peoples. Therefore it is not only those who own much and give much who are to be praised and mentioned for their hospitality, but in particular those who find ways of giving, even though they are not well off. Those who give generously and openheartedly are bidden farewell joyfully because they have treated their guests well. On the other hand, those who take guests in unwillingly or with a frown, although they offer them food and drink, are referred to as follows: “He filled our bellies with food and drink as if we were oxen, but we are human beings. He may have given us everything he had, but he did not have that drink with which the Albanians quench their spiritual thirst…” In fact, it is not difficult to welcome and host Albanians because you can give them anything, but you must give it openheartedly. This is why those who are poor are not put to shame for the little they have to offer, and this distinguishes them from the rich who have enough but do not welcome their guests as well as the poor do. On such occasions, people say: “You may have more than enough to give to your guests but you do not have the heart and respect for them that I do. My house is open. My guest will not look down upon me because he knows that I would give everything I have, even my life, for him.” As I said before, it is a great honour for an Albanian to be able to give what he has to his guests. He is in pain and deep despair if he has nothing to offer them. I will give you an example of such pain and deep despair. During the reign of a Bushatli vizier, an Albanian robber from Hoti was waylaying travellers on the road from Shkodra to Rapsha. The vizier offered a large sum of money to catch the perpetrator. As such, after a certain time, he was caught and brought before the vizier who asked him: “Tell me, why are you making all this trouble?” “Just for fun, Milord,” replied the robber. “I then sentence you to death,” said the vizier. “May it be!” replied the robber who was taken away to his place of execution. The henchman followed him with a sword in his hand, ready to chop his head off. When they arrived at the appointed place, the vizier said to him: “Come over here, Albanian, because I want to ask you something.” The Albanian turned. The vizier and the men around him watched the robber approach them in a leisurely manner, though with his hands in shackles, as if it were some matter that did not interest him at all, or as if they had called him over to ask him a simple question. When he was face to face with them, the vizier asked him: “You have acted like a man for all the crimes you committed, but I would want to ask you a question and would like an honest answer from you.” “Speak and ask your question.” “You have committed many crimes that were grave and involved much effort. But I now want to know from you – were you ever in such a predicament as the one you are in now?” “Yes, I was. I was once in a far worse situation.” “What happened to you that could be worse than what has happened to you today? The henchman is standing behind you and is about to chop off your head in a few minutes. Think carefully. Was there ever a worse day in your life than today? Tell the truth. Do not shame yourself with any lies to all these people who are looking at you and listening to you.” The Albanian looked around at the henchman who was standing as straight as a statue with the sword in his hand and watching the vizier to carry out his orders immediately and to do his job in one fell swoop. Having looked at the henchman for a moment, he turned his head, raised his eyebrows and set to speak. All those present were convinced that he was going to beg the vizier to have someone else chop his head off and not that terrifying gypsy with long and sharp teeth who was holding the sword ready. There was an expression of cynical pride on the henchman’s face that made it evident to the vizier that, at the slightest nod, he would slice the robber’s head off in one fell swoop. The Albanian, however, had no intention of pleading with the vizier and did not ask for another henchman. He looked straight at the vizier who repeated the question, saying: “Speak up like a man. Have you ever been in such a predicament, Albanian?” “I already told you, I was in a worse situation, in fact twice.” “Tell us what happened.” “There were two occasions on which visitors came to my house and I had nothing to offer them for dinner and they were forced to spend the night without food. Those two occasions were much worse for me than what is happening now because I am sure that what takes place today will soon be forgotten, but those two events will be remembered forever.” Having spoken the robber looked overwhelmed by the memories and blushed in shame. Those around him were amazed to hear that, in the face of death, he suffered more from the thought that a guest of his had gone without dinner than from the thought of his own death. The vizier, too, was deeply moved, and gave orders for the robber to be released and allowed to return to his home unhindered, to his tribe in Hoti. Death from a Loaded Rifle This Albanian behaved placidly in the face of death by the sword, as did many others caught by the vizier and sent to their deaths by sword. The vizier did not kill them immediately, but first he took their weapons away. It is considered a great shame if someone is shot right beside you and his rifle is left there fully loaded. You are obliged to take his rifle and shoot back immediately so that, when the enemy arrives, he will find the rifle empty. When an attacker approaches his dead or gravely injured foe and finds his rifle emptied, he is proud since it shows that his opponent was courageous because he fired his weapon and fought to the death, and was not a coward who could be slain easily. The Hoti fellow I mentioned earlier was courageous and had killed many a man, but he was not able to slay the vizier’s men who caught him. He was thus too ashamed to sing on his way to the town of Shkodra where they were taking him for execution. I will mention some of their names later when I discuss them because an Albanian, in such circumstances, goes to the gallows or to the henchman singing, right until the moment his head is sliced off. The Albanian people sing of such heroes in their folk songs. Their names are held high, not only by their families, but also by their relatives and their whole tribe, and especially by their blood brothers and friends. Some of them had many blood brothers and friends. It is after all understandable that the more blood brothers and friends you have, the better a person you are. When they sing folk songs about someone, their greatest wish is to have been his friend and to have been close to him. They say things like: “We ate bread and salt together in the home of someone or other.” This is enough to be able to call yourself his friend, even if there were no further contacts. As I said earlier, if you pay honour to an Albanian, however small it may be, he will recognise it and endeavour to pay you back. About this they say: “Someone who has taken the path of little acts of evil will soon end up by committing large ones. Someone who has taken the path of goodness, however small the acts may be, will end up by doing great deeds of goodness, as many as his soul and noble heart will permit. He will not be indebted to anyone, and least of all to God. Earlier, we saw that an Albanian who dies a heroic death singing, gains great respect and many songs are made about him. These songs praise his deeds and sayings. The songs pay tribute to his mother, his father, his brothers and sisters and tell his people not to mourn him because he died a hero’s death and thus did not put them to shame. Therefore, they should not shame him by weeping for him. These songs also pay tribute to his friends and blood brothers “because he left no shame behind.” Everyone leaves his weapons to someone, telling them to use them with honour, to die a hero’s death themselves and not to shame the benefactor in his grave. They embellish his heroism in the songs. As such, neither a mother nor a father would ever wish that their son return to life and that such songs no longer be sung. The Albanian people are proud of their songs and memories. Whole generations take pride in what is said in them. [Excerpts from Marko Miljanov, Život i običaji Arbanasa, Belgrade 1907. Translated by Robert Elsie.]

The Montenegrin warrior Marko Miljanov (1833-1901).

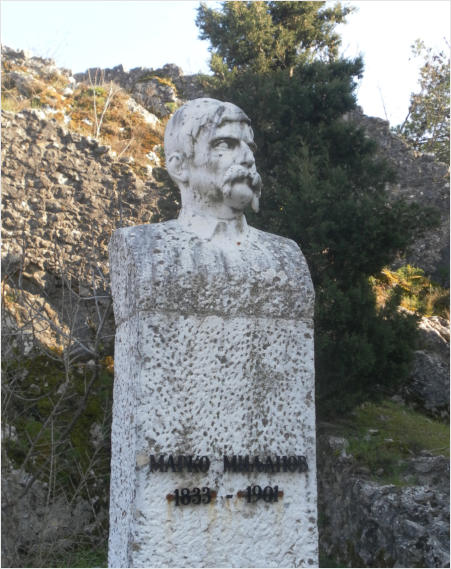

Bust of Marko Miljanov at Medun, Montenegro

(photo: Robert Elsie, March 2014).

Old motif in a graveyard in Triepshi (Zatrijebač) tribal territory,

Montenegro (photo: Robert Elsie, March 2014).

| Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact |