| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1908

Alexandre Baschmakoff:

A Perilous Journey through Northern Albania

and Down the Rugova Canyon

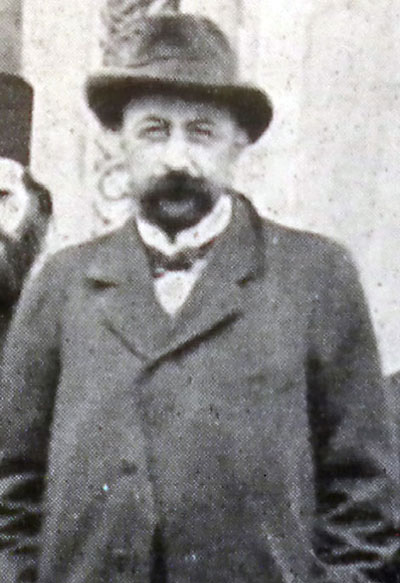

Alexandre Baschmakoff, 1858-1943

(Photo: Alexandre Baschmakoff, September 1908).

Alexandre Baschmakoff (1858-1943), known in Russian as Aleksandr Aleksandrovič Bašmakov, was a Russian writer who lived in France, at least from the time of the Russian Revolution. He is remembered for his French-language book, “A travers le Monténégro et le pays des Guègues” [Through Montenegro and the Land of the Ghegs], Saint Petersburg 1911, an account of his journey through Montenegro, northern Albania and Kosovo in September and October 1908 to survey the region for a railway line that would link Serbia and the Adriatic Sea. The journey took him from Cetinje to Tuz, up the Cem [Cijevna] River valley through Gruda and Kelmendi territory to Gucia [Gusinje] and Plava [Plav], and down the Rugova Canyon into Kosovo, where he visited Peja, Deçani, Gjakova and Prizren. From Prizren he returned to the coast via Kukës, Puka, Vau i Dejës and Shëngjin. For a foreigner, and in particular for a Russian among the lawless, gun-toting Ghegs, the journey was fraught with danger and he was thankful for the assistance and loyalty of his Albanian guide, Zef Doda of Triepshi. It was in the Rugova Canyon that the journey became particularly perilous.

In the Lim Valley

After having said good-bye to the hospitable parents of Zef Doda, I could not leave Selca without paying a visit to the Catholic priest who lives there.

The church he serves is situated on a high plateau where the road leads through such precipices that we had to get off our horses and continue on foot over a towering bridge that spans two cliffs. Below us, the Cem/Cijevna River made its way noisily through the dark and narrow crevasses in the rocks and, bending over the feeble construction to have a look into the damp and dark abyss, I had the impression of being shrouded in the cold air of the grave.

The Franciscan monk, who was about forty-five years old, was waiting for us at the door of a church that reminded me of an Italian monastery. The monk was dressed in a dark brown cassock held together by a cord serving as a belt. In his hand he held his rosary beads, and his tonsured head was covered by a skullcap much like the traditional Albanian ones. Father Joachimo Sereti invited me cordially to enter his home in which the chimney was replaced by an Albanian hearth. It did not smoke because he had a flue leading outwards. Despite its size, this home was very much in Albanian style. It was evident that, despite his upbringing in a Florentine seminary, he made no attempt to distinguish himself from his Albanian parishioners, i.e. he was no different from the members of his flock, and was certainly an interesting figure.

“Zef Doda, a Christian Albanian from Triepshi in

Montenegro, and his wife, a native of Podgorica”

(Photo: Alexandre Baschmakoff, September 1908).

He had the falcon eye of his people, a glance that however could be supple, dominating and gentle. Altogether, he was a complex and charming figure, a Franciscan lost in the profound solitude of this isolated region where he had lived for twenty-seven years amongst this savage population. He was never bored since he was part and parcel of the people here. We began our conversation in Italian, but since my knowledge of that language was sketchy, we then turned to Latin, which gave us better results. I soon realised that he was an educated man. He showed me his school, the walls of which were covered in scenes of Bible history. We had ourselves photographed together and I promised to send him a copy. Father Sereti said farewell with compassion. He embraced me, saying, “Desidero tibi bonam sanitatem, viator! Desidero ex plenitudine forte amantis cordis albanensis!” (I wish you good health, traveller! I wish this to you from the bottom of my loving Albanian heart).

We got back into our saddles and after journeying for an hour up the slopes, we got above all the scattered homesteads of the bajrak [tribe] of Selca.

Now the route took us up into the mountains and, after we continued for an hour or two, the valley widened out and we passed by some shepherds’ huts called Kolibeja e Gropës. It was here that I learned that the word kolibe, which the Macedonians use in the sense of a cottage, came directly from the Albanian kolibe, meaning ‘hut.’

After this, the valley became narrow again, the Cem River flowed in cascades, and the forests were dense and the vegetation rich. However, we had no time to rest in the shade of the forests and, continuing our journey along arid trails, we began to climb up along precipices. A cold wind blew down on us from the pass. We finally reached the Predelec [Bordolec] Pass and cross over to the other side where everything was different. The water flowed not into the Adriatic but towards the Lim basin and from there towards the Danube and the Black Sea. Even while approaching the summit, we noticed that the rock formations were different, as were the flora and the people.

We knew that on the one side of the Predelec Pass, the Albanians were peaceful, but now, there began a region of fierce men. The people of the one side, of more gentle ways, were wont to say with some trepidation: “If blood flows, it is always over there.”

The clouds dissipated on all sides, the gorges disappeared and we proceeded over vast alpine meadows. This was pastureland surrounded by rocks and dense forests called Han Gropa, three hours from the bajrak of Selca.

From there, one can reach the top of the pass in three-quarters of an hour, i.e. it is three or four kilometres away. The region is particularly intriguing for those interested in changes in nature. […]

At about two o’clock we arrived at the top of Predelec Pass (1,350 m. above sea level). It was hard to imagine that we were at the water divide because there was nothing to be seen. We were surrounded by dense forests. On the other side of the pass, wide trails enabled us to descend more easily. This region reminded me of the water divide between the Ob and Yenisey rivers in the Alatun taiga and the Tashtyp Pass where, in a dense forest, it was impossible to see in which direction the water was flowing.

After descending through the rich natural environment for two hours, we reached the junction between two torrents, the Lëpusha and the Vermosh, that form the Grnčar River which in turn flows into the Lim. Looking to the left up to the head of the Vermosh valley, we could more or less see the pass and the upper part of the Skrobotusha torrent that flows from there down into Montenegro. We asked about it and were informed that it was easier to reach than the Predelec Pass. However, the construction of a railway line would be easier along the route we had just taken in view of the difficulties behind the Skrobotusha Pass and down the Morača River valley. In general, it would seem that a rail line down the Cem Valley would present no particular difficulties, although a tunnel would need to be built under the Predelec Pass.

I estimate that a line from Podgorica to Gucia/Gusinje would be eighty kilometres long, of which sixty kilometres would be up the valley of the Cem, i.e. from Podgorica to the Predelec Pass.

After wandering at length through the narrow valleys where we encountered no smile of nature and where we even had difficulty getting a brief glimpse of the sky because we had to concentrate all the time on our horses and the deep gorges beside us, what a delight it now was to descend into the rich and open countryside, the verdant fields of the Grnčar River valley. This region was surrounded by high mountains, a grandiose background providing a scene of tranquillity and grace. The dark hills were the Greben peaks, the foothills of majestic Mount Vizitor to the left, and the Trojan, the first chain of the great range of the Accursed Mountains (Prokletije) on the right. They remained in the background, giving much room to the Grnčar valley.

“Huts at Kolibeja e Gropës before the Predelec (Bordolec) Pass” (Photo: Alexandre Baschmakoff, September 1908).But why did we not come across a single village in this seemingly happy and blessed valley? Only rarely did we see a sombre Albanian kulla [fortified tower] looming above us, the spitting image of the manor of a “Raubritter” in the early centuries of the Middle Ages. We were soon to get an answer to this question.

About an hour before we reached Gucia, we were taken unawares by the sound of uninterrupted firing. The sun was already low on the horizon and the shades of night were spreading ever faster. As such, we spirited our horses onwards, knowing that in Albanian land, and especially now that we were in the very heart of Arnavutluk [Albania], we could not travel at night without getting shot at. The firing was getting closer and closer, and was more intense because it echoed in the high mountains.

“Where are they shooting?” we asked the people we encountered.

“Oh, at Gucia, they are celebrating the start of Ramadan.”

As we learned, the Muslims were wont to celebrate the last day before the start of the long fasting period of Ramadan with much ado. There was a veritable orgy of gunpowder fired off that day.

In a normal place where law and order reign, such a shoot-out would be nothing to fear. It would only be a bother to those wanting to get some rest or sleep. But here, where the soil is drenched in the blood of Christians, in this valley between Gucia and Plava/Plav in the heart of the Muslim world where the chances of a Christian passing through without being shot to death were like winning a lottery, such joyful gunfire meant danger to life and limb for the few Rayahs still left in this country. They all remained in their homes and dared not even look out the window. Yet fate had it that I should arrive in that isolated corner of Arnavutluk for the first time at nightfall, in the midst of a wild shootout of fanatic Arnauts [Muslim Albanians].

By the time we reached the houses of Gucia, night had already fallen. Suddenly, at a turn in the street, we found ourselves in the middle of the çarshia [bazaar]. In the dark, we could barely make out the faces of the Arnauts resting on their heels in front of the shops around the bazaar. On their knees they held their rifles tilted upwards and accompanied every shot with wild cries that seemed to me to express not joy, but savagery and hatred towards us.

The gunpowder fired in the dark reminded me of wisps of blood in the air and our horses jumped in terror despite all of our efforts to keep them under control and pass slowly, in calm and dignity, through the inferno of cries and bullets whizzing over our heads. Had this scene lasted a few minutes longer, it would certainly have ended in blood, but the Turkish police did everything they could to avoid us being massacred. An officer led us to the police station and bolted the door behind us. The kaimakam [government representative] soon arrived in haste. He was of pure Turkish origin and had recently been appointed here. The poor man risked being killed at any moment by the Arnauts who do not stand on ceremony when it comes to non-Albanian kaimakams and mutasarrifs [governors], and slaughter them at the slightest pretext.

One could see that the kaimakam was very agitated in view of the scene we had just experienced. We were surrounded by all sorts of Turkish officials sitting on the divans around me and welcoming me, some with expressions of curiosity and others of fear. For over an hour they treated me to coffee and cigarettes and seemed undecided as to whether they should allow me to proceed to the local han [inn]. Exhausted after my ten-hour ride, hungry and covered in dust and dirt from the road, I was forced to put up with all manner of ceremony until the shooting died down and the savage cries and echo of the drums subsided. It was a diabolical and chaotic scene conveying a relatively clear message: “Death to the Christians, death to the infidels,” or as they say here kafir, i.e. any Christian who had the nerve to turn up at Gucia where anyone of Christian faith is to be put to death.

Finally, my torment came to an end when it was completely dark and the shooting stopped. The kaimakam led me and my entourage personally to his home and gave me an excellent dinner in Turkish fashion, and then took me to a bedroom which was exceptionally clean for a Turkish house. He thus gave me an opportunity to rest and get a bit of sleep. This fellow probably risked his life by offering me hospitality and protecting me from the bullets and daggers that could have reached me at the inn. The chaos in town was such that even the suvaris [horsemen] escorting us, although they were themselves Muslims and policemen, took quite some time before daring to take the horses out to drink.

Plava and its Chieftain

Despite his hospitable nature, the kaimakam was delighted early the next morning when I set off because the malevolence of the Arnauts towards me was so great that a longer stay in town on my part would have caused him serious problems. My travelling companion, Zef, who had met members of his clan in the local population, told me some very interesting things, bits of conversation he had heard about me. The enraged Arnauts had gotten together and said that they ought to kill the kaimakam who had had the impertinence of offering refuge to a Russian. Fortunately, less extreme opinions won the day. About me they said, “As to this infidel, let him have as many soldiers as he wants, it will still not stop us from killing him.”

Before leaving, I had long discussions with the kaimakam and the officer of the Albanian gendarmerie before deciding which route to take from Plava to Peja [Peć].

They endeavoured to persuade me to take the direct route to Peja over the mountain peaks without descending through the villages called Rugova as the inhabitants of those villages had the worst possible reputation as faithless brigands. A mutasarrif had been killed there two years earlier and I noticed more than once that people in the administration and even soldiers spoke in horror of Rugova. To divert me from my plan of passing through Rugova, they assured me that there was a pass south of the Qafa e Diellit that led directly to Peja. I explained my problem to them, informing them that I was in search of the best route for a railway line (of which the Turks were all in favour). As such, I was unwilling to abandon my plan and to take a trail circumventing Rugova.

“Do not worry about my safety and my speedy arrival in Peja,” I told them. The most important thing for me was to cross over the pass under which it would be easiest to bore a tunnel and get as low as possible into the valley, i.e. Rugova. “If it is a den of thieves,” I added, turning to the Albanian captain, “you should know, canim [my dear], that the Russians and the Turks are quite alike. Both have given proof of their bravery in battle. If it comes to a fight, I will stand with you and your soldiers, and God will not abandon us.”

A çaush [adjutant] was summoned who knew the mountains beyond Plava and was asked: “Which is the lowest crossing to get over the Mokra Planina: the Çakor Pass, the Vlagajnica, the Qafa e Diellit, or the route over the peaks to Peja?”

He responded without hesitation: “The lowest one is the Qafa e Diellit which is the shortest route to Peja through Rugova.” From Gucia to Peja it was fourteen hours by horse.

“In that case, this is the route I must take,” I replied, and the local authorities agreed to give me permission.

We left Gucia in a group of nineteen men: myself, Zef Doda, Jacob who was my kiraxhi [caravan leader] with three horses, a çaush on horseback and a zaptieh [gendarme]. With us were fourteen foot soldiers armed with Mauser and Martini rifles. Most of these men were Turks from Asia Minor, all young and probably never having been in battle. Half of them were robust peasant lads shouting songs from their Anatolian villages at the top of their voices. One of them, an Asian of a particularly lively temperament, jumped around, danced and cried, despite the fatigue of Ramadan which did not allow him to eat throughout the daytime. The other half were beardless youths, narrow breasted and underdeveloped, quite outdone by a journey through the mountains. […]

“Dus Muslia and Ibrahim, brigands from Rugova” (Photo: Alexandre Baschmakoff, September 1908).Nowhere along the road did I encounter a single Serb, only Muslims The kajmakam had told me that Gucia had 800 houses (equivalent to a population of 4,000 souls), and Plava had 600 houses (i.e. 3,000 souls), of which it was said that there were only 60 houses (300 souls) of Christian Serbs living in Gucia and 30 houses (150 souls) of them living in Plava. From these statistics one can conclude that this rich valley of the Grnčar and Lim Rivers, from Predelec to the top of Mokra Planina contains hardly 500 Christians of Slavic race. All the rest had turned Turk, of course by force. In contrast, almost all the names of rivers, villages and mountains were Slavic.

For example, as we carried on along the south bank of Lake Plava, along from the southern slopes of Mount Vizitor, I was shown a village called Martinovići [Martinaj] which was inhabited entirely, it seemed, by Muslim Arnauts. The Christian population had disappeared without leaving a trace. One had the impression of crossing a vast cemetery of the Serb race.

Two hours after leaving Gucia, we reached the town of Plava. My askier (infantry troop) sat down and waited in front of a shop while my horsemen and I set off to the home of the Albanian chieftain of the town, the head of a band of formidable brigands, called Aso Ferovich. As he was not at home, I returned to my askier while men were sent out to find him so that we could meet him at the bazaar. In the meantime, I opened up my camera and was busy putting film in. I was soon surrounded by a group of Albanians examining the curious beast that I was.

I was later told that they had spoken of me with great animosity and behind my back, some of them had made signs indicating that the infidel ought to be chased away. They also insulted me in a low voice in Albanian. But as I was busy with the apparatus, I noticed nothing at the time. All of a sudden, the crowd surrounding me opened up, full of respect, and a man about forty-five years old approached with an air of royalty.

He was a vigorous and amply muscular fellow and his face bore an expression of dominance. His eyes reminded me of the Mongols and his piercing glance was candidly sly. He carried no weapon as if to stress that he did not need one.

This was Aso Ferovich in person.

The reputation of this man was known well beyond Plava. I had heard of him in Montenegro which at that time had concluded a besa [truce] with him. I had been advised to conclude a besa with him, too, as this was the safest way of keeping my head on my shoulders, even if I had no escort with me, because all the sinister forces at work in this country were under his control. Some people had warned me about him, saying: “Be careful of Aso Ferovich! He hates Montenegrins and is in the service of the Austrians. Any deal you make with him will be a waste of time.”

On the other hand, I had also been informed that during the famous siege of the Monastery of Deçan/Dečani by Albanian bands in 1902, Aso Ferovich had refused to take part and had shown his good intentions towards it. I was also told that Aso Ferovich owned a kulla at the source of the Komarska River, a dungeon that bore traces of grapeshot evincing the vain attempts of the sultan’s troops to destroy it. At that time, he was at peace with everyone, but how long would that last? At any rate, his power and influence in the country were such that it was enough for him to raise his standard and give out a war cry over Albanian land for volunteers to rush to arms from all sides to support him. The Christians trembled whenever they heard that this wolf had left his lair in the forest and was on the prowl.

Aso Ferovich invited me into his house near the bazaar in a dignified and chilly manner. He showed me to the room upstairs which was well-lit and clean, furnished in oriental fashion and embellished with all sorts of rich objects there to be seen. There were rugs everywhere, mirrors in golden frames, heavy pistols plated in silver filigree, a woman’s costume decorated in heavy gold coins, a few objects reminiscent of European comfort as curiosities from ‘overseas,’ as well as select arms and various textiles covering the walls. The master of the house introduced me to his younger brother who resembled him a lot. They both had the same Tatar eyes scrutinizing me in a not particularly friendly way. He was heavier set than Aso. His hands resembled shovels yet, despite his immense stature and physical vigor, he seemed submissive and respectful to his elder brother, the chieftain.

“The Serbs of Peja conducting the burial of the head of a Montenegrin warrior, cut off by the Albanians of Rugova”

(Photo: Alexandre Baschmakoff, September 1908).Aso Ferovich invited me to stay with him and even spend the night, but I refused, saying that I was being expected in Prizren and still had a long way to go. He was unpleased at my refusal and I endeavoured to make good with the following remarks:

“Aso! I cannot stay with you today. I will write you from Saint Petersburg and let you know when I will be coming back. Then I will be honoured to stay with you and we will climb to the top of Mount Vizitor together.”

But the conversation flagged. He spoke little Serbian and I had to express myself through my Albanian interpreter. I explained that the purpose of my journey was to study the potential routes for the construction of a railway line which would bring wealth to everyone. He listened closely, but reacted as if to say, “I am wealthy enough as it is.” He took interest in the project, but was indifferent to everything I said about the works being carried out with a firman [imperial permit] from the sultan.

It was as if he were saying, “My armed companions and I are the ones to issue the firmans here.”

I offered to take a picture of him and the men around him. He replied initially, “If you wish, you may photograph us.” We then continued talking about my trip. He advised me not to go through Rugova, but when I explained to him that we were not afraid of anything but wanted more details about the people of Rugova, he gave no further explanations and simply said, “Fine, why not go that way.” He seemed to wish to avoid saying anything bad about the men of Rugova.

We spoke once again of the photograph, but he refused this time, adding, “Alright, when you come back next time, you can take my picture.”

Our conversation was now unpleasantly chilly and aloof. I looked at my watch and told him that it was time for us to leave. He accompanied me to the bottom of the stairs, saying, “It is here that we must say farewell to one another.” We were without witnesses.

We embraced in Albanian fashion, i.e. cheek to cheek without a kiss. He offered me no besa and, in view of the chilly tone of the conversation, I did not wish to ask him for any guarantees. His brother simply told Zef that he would see to it that we could pass safely through a neighbouring village where he had once spent several weeks when he had been injured by a bullet. That was all.

Thus, we set off without any guarantees which, according to local custom, meant that neither Aso Ferovich nor his subjects were particularly interested in our safety. Our heads were up for sale. We thus took our leave, counting on luck and relying on our weapons.

The Qafa e Diellit Pass

The journey from Gucia to Peja lasts no less than fourteen hours, which means about five kilometres per hour. The trail conditions were not bad, the route being neither steep nor rocky. Over certain stretches we probably did more than five kilometres an hour.

Knowing that sun sets in the mountains at six o’clock in mid-September, we realised that by leaving Plava at eleven o’clock in the morning, we would not be able to reach Peja that same day. We therefore had to spend the night in the mountains. From Plava to the summit of Qafa e Diellit it is about three and a half hours, and from there to Rugova it is another three and a half hours. Consequently, the normal place to spend the night would have been Rugova, but we knew that such a choice would have been naïve on our part and we would not have wished such a thing on our worst enemies. We had to avoid spending the night there. We also hoped that no one would find out in advance where we would be spending the night. Rugova is not a village. It is rather a series of huts scattered at random in three directions one or two kilometres from the junction of the valley of the Bistrica and an inflowing torrent. The name is significant because rruga in Albanian means road.

In reality, Rugova is thus a crossroads, the easiest meeting point for pillaging and killing travellers.

Having considered the matter for some time, I ordered Zef to tell my escorts that we would be spending the night in the han located in the forest one hour from the top of the pass. In addition to this, we also spread a rumour that we would not be carrying on to Peja directly the next day, but would be advancing westwards towards the settlement of Berane that is situated twenty-five kilometres from Rugova on the Montenegrin border. Finally, we decided to leave the han before dawn, but say nothing about this and give the impression that, exhausted by the journey, we would be sleeping in until later in the day. There is no doubt that it was this trick that saved our lives.

Leaving Plava down the high valley of the Lim, we turned to the northeast and soon crossed the Komarska River, after which we climbed the slopes of the mountain not far from the village of Komare.

(front row from the left) French ambassador in Belgrade Mr Descos, the monk Cyril and the author in front of the portal of Deçani (Photo: Alexandre Baschmakoff, September 1908).Our trail penetrated the forests between two mountain ridges, leaving Metej to the south, a point indicated on the Austrian military map. This is obviously not a village but rather a common designation for the forest pasture land and anything found around this area. The terrain over which we progressed was made up of yellowish soil with thin trees, being mainly chestnuts, walnuts and beeches. As we reached the pass, the landscape was barren and the climb was steeper but without precipices. We came across strata of slate and at the top of the pass we encountered various types of quartz. We could now see into the distance, but a cold wind blew down from the heights. We still had another hour to climb to reach the summit. […] The pass provided an expanse large enough for us to put the horses out to pasture. All of my askier stretched out in the grass, exhausted by the climb and from lack of food because of Ramadan. The young soldiers were soon all sound asleep in the pure mountain air. My zaptiehs, my kiraxhi Jacob and even Zef followed their example and soon, all were dosing with their Mausers, Martinis and daggers in their hands. […]

Zef called out to me. “I have been looking for you. Why have you wandered off from the group? Who knows what can happen here?”

“What have the soldiers been saying about Rugova, Zef?”

“What can they say? They are talking a lot. Some of them are afraid because they know the trail is dangerous. You know, two years ago, a kaimakam was murdered at this very spot, and he had his askier with him. The people of Rugova are complete savages!”

“But do you know what they are saying about you?” continued my faithful Sancho Panza. “They say that it is your head that is in greatest danger. They say that there is only one way you can survive. As soon as we start the climb downwards, you must put away your Russian hat and put on a Turkish fez or, better still, a white Albanian cap. They are right. It would be better for you to do so, because in case of attack, it is you who will be the target of any fire.”

“My dear friend, Zef,” I responded, “If I put on a fez or a white felt cap while I have a whole detachment under my orders, they will say that the Russian was afraid. Let all the Christians know that the Russian passed through this country with his head held high and that fear was unknown to him. They address their prayers to Russia during the pogroms. A Russian must not betray their confidence by showing fear. If we are shot at, let them shoot at us. We will defend ourselves and God’s will will be accomplished.”

My Serbian kiraxhi came up to us, and a wretched sight he was – taciturn, sullen, like one of the rachitic peasants one encounters in Russian villages. Taking up our conversation, he stated with noble sentiment, in stark contrast to his appearance:

“Yes, I knew he would answer that way. A Russian can answer in no other way. To put on a fez out of fear would put him to shame. Yes, one can expect no other answer than this from a Russian.”

While he was speaking, this poor devil revealed his twisted, exhausted shoulders. He wore dusty sandals on his feet and an obligatory fez on his head.

“You know,” he continued, “while we were in Plava, there was a poor Serbian priest who wanted to see you, to talk to a real Russian and shake his hand. But you were with the ferocious Aso Ferovich. He was afraid of approaching you because you were surrounded by savage Muslims. He was even terrified of leaving his house. He watched you through a slit in the door because he was too afraid of being seen at his window. Similarly, the Serbs of Gucia did not dare to go out during the Ramadan shooting because they were afraid of being shot. All the Christians were in hiding. That is why you did not see any of them.”

The sun was already setting behind the rocky mountain peaks, transforming the warm colours into shades of violet and dark purple. Our soldiers awoke, saddled their horses and we set off through the dense forest on our way to the mysterious and unknown han.

The Vultures’ Nest

It was the dead of night. A profound silence held sway around us in the ancient forest, interrupted only by the roar of a mountain torrent. We were already within the walls of a two-storey stone han. The horses and the other animals were on the ground floor. The upper floor consisted of two large rooms without any furniture at all, and no windows in the sense that the reader would understand the term. One cannot call the two foot-high, glassless openings in the thick wall windows. They are there as loopholes for rifle fire because these walls can even withstand the fire of mountain batteries.

The Luma Bridge (Kulla e Lumës) near Kukës (Photo: Alexandre Baschmakoff, September 1908).Between these openings that allowed some air in, there was a sort of chimney consisting of a semicircular stone plate on the floor and supported by an exterior wall in which was situated the flue, thanks to which the smoke did not fill the room entirely. Here we settled in for the night, twenty-four men in the same room, without the air being too stuffy. The smoke bothered us from time to time but the air remained breathable. After a light dinner, our soldiers lay down in two rows and slept like logs. Only Zef and I remained awake, not to mention the owner of the inn, whom I would now like to describe to the reader.

Our host, the hanxhi [innkeeper], much resembled a vulture. He sat on a low perch at the fireplace and observed me intensely. I was seated on the other side of the fire on rags and packsaddles. This was the best they could do for me. The old vulture stared at me from under his thick eyebrows. There was no sign of a smile on his face, no words of welcome from his mouth. He was wearing a costume made of white cloth, as do the Rayah. He had no weapon or any sign of Arnaut luxury. His limbs were not muscular and one could see that the old zuber had long renounced any claim to youth. His old bones crackled, his voice was windy and his tired eyes emitted hatred. His job was to pour the tea and it so happened that it was excellent Russian tea that he was serving us. From time to time, the old wolf issued orders. His subordinates looked at one another and left the room mysteriously to accomplish some task or other before they returned, always looking busy. […]

The main figure of note, however, was Ibrahim, the son of the hanxhi, a splendid Albanian type with a long silky-blond moustache, an aquiline nose, a slim build and steely blue eyes as piercing as daggers, eyes that were cold, without the least glimmer of fire in them.

All of his movements were supple and intriguing, like those of a lynx or a panther. He wore a richly embellished cartridge belt and had a short, lightweight and elegant rifle with him. Ibrahim examined me with particular curiosity, but not with the sullen marble glance of the old man. He was edgy and whenever I looked at him, he turned away and began talking to Zef as if to convince him tenderly of something or other. He was over thirty years old and slender in build, but the first appearance of him was deceptive. In reality, he was a cat with steel muscles and the endurance of a wild beast.

Finally, there was the most savage of all the inhabitants of this region, the shepherd Dus Muslia, a lad of some twenty-two years – no moustache, slender, resembling a jackal. I had never seen eyes like his. They shone from under the sheepskin he was wearing, two lights radiating in the darkness like the eyes of a cat. Wanting to test him, I lay down for several minutes and pretended to snore, but watched him all the while through my fingers. Dus Muslia rose suddenly, leaning on one elbow, and stretched his thin neck in my direction. He devoured me with his phosphorescent eyes like a wolf, and then made some mysterious signs to Ibrahim.

Ibrahim went over to the window-like opening in the wall beside my feet and gave a piercing whistle, a signal to the dark forest outside. I heard a muffled reply from the forest. What could this mean? How many were they? I called Zef over with a gesture. He too had been pretending to sleep. He crawled over towards me and we exchanged our impressions of what was happening.

“Something is going on,” he said, “and it is not good. These are Rugova people, you know.”

By this time, our wolves were talking in an agitated manner, but in low voices, among themselves. We could hear them repeating the words “Berane, Berane.” This proved to me that the rumour we had spread had taken hold. I was convinced that if they succeeded in setting up an ambush with the men of Rugova, it would be somewhere between the inn and Berane. Zef and I decided to stay awake until dawn. Zef began to engage the brigands by talking to them in Albanian. There they were, my faithful guide and the treacherous Ibrahim, with their arms around one another’s waists, conversing like two close friends. I later learned that under the appearance of such camaraderie there were sombre words and bloody allusions exchanged.

“You are in no serious danger here in Rugova,” said Ibrahim to Zef, “but that Russian of yours will have some trouble. He will not keep his head on his shoulders for long.”

“Come on, Ibrahim, we are friends and can reach an agreement, can we not?” replied Zef diplomatically. “Let us be brothers. With the help of God and by prayer we will prosper.”

A smirk covered Ibrahim’s face: “What is all this talk of God and prayer? We do not recognise such forces here. We rely on a steel blade and a good carbine. That is our divine intervention.”

Dus Muslia naively betrayed their pact. Turning to Zef, he winked, indicating the corner of the room where I was lying, and began to laugh. Then, closing his left eye, he raised his hand to his right eye and began moving his index finger as if pulling some invisible trigger. “Ha, ha. What splendid game we have here!” he seemed to say. “This would be a good one to shoot.”

Zef could hardly keep his calm during this strange murmuring in Albanian. Ibrahim tried to win him over again:

“You know, Zef. There was another case like this in Rugova. A rich Christian merchant who had become a Muslim came over from Podgorica with a lot of merchandise and only one servant. Our men said to the servant: ‘Choose between death or twenty gold Napoleons.’ He was no fool, and followed our advice. We did away with the Podgorica merchant in no time, and our companion is now a rich man.”

Zef could not hide his indignation: “Ibrahim, I do not want to hear any such tales. Neither the Russian nor I fear death. We are ready to defend ourselves and confide in God. We are not afraid of you at all.”

Ibrahim replied in a sinister voice: “Oh, brother Zef, you have never seen brave men like us. I will soon show you what a real hero is.”

I called Zef over. “Ask how old the hanxhi is!”

The old man replied that he was fifty years old, although he could easily have been seventy.

“Why does he look older than he is, and why does his son Ibrahim look older than his years?”

The response was unusually candid. “They say,” Zef translated, “that they live difficult lives, that they spend their nights watching out for human game passing through the forest and never get to bed before dawn.”

They spoke of their criminal profession with the innocence of men who had no idea that it was shameful pastime. Indeed when they spoke of blood, their words took on an air of pagan delight. There was no greater joy for them than to spill blood. Their beings derived power and sensual delight in it. […] The foster father is a murderer. You want to eat? Well, kill and you will be replenished. If you have grown rich from your pillaging, spend your money on precious weapons such as those of Ibrahim. These weapons are our ‘means of production.’

At about one in the morning, Ibrahim got dressed, put on his cartridge belt, threw his carbine over his shoulder and, without saying good-bye to anyone, disappeared, only to turn up again at two in the morning. Where had he gone? Probably quite a distance because he seemed to have been on a long hike when he got back. It was obvious to us that the inhabitants of Rugova had been told to set up an ambush.

After Ibrahim’s departure, our conversation with the brigand Dus Muslia took a new turn and enabled me to make some interesting discoveries with regard to the Albanian epic in its most primitive form.

“Highland Ghegs of the Dukagjin tribe near Koman on the Drin River” (Photo: Alexandre Baschmakoff, September 1908).I heard the old wolf murmuring something between his teeth, reciting a text with four strong accents per phrase. It was something that resembled an ancient iambic metre. This aroused my curiosity and I did what I could to put my assassin in a good mood in order to pick up a fragment of his incomplete poem. I placed a crown in his hand and Dus Muslia rose and assumed his new role as a rhapsodist. He sat down at my feet while Zef, preparing to translate what he was saying, lay down beside me. I took my notebook out of my bag and was given a weak lamp. Under these unusual conditions, our philological exercise began, with a murderer as the professor and someone possibly to be slain in a few hours’ time as his student.

The first fragment was devoted to the heroic death of Shcherbina [Russian consul in Mitrovica], murdered by a fanatic Muslim in Mitrovica. Dus Muslia sang:

Mitrovitz um bám betéli,

Kortsul ozen evráun neféri,

Mór nefér pash din eimón

Kush tka shtin, kush tka thon…“There was a fight in Mitrovica,

A simple soldier killed the consul.

How did your faith help you, soldier?

How did it give you force for such an action?

No one forced me, no one gave me the right,

The force came from my profound faith”…Before me all the secrets of an unknown world were being played out. The cruel, stupid and abominable act of killing Shcherbina was being described here as a noble deed. The moral interpretation made by these fierce Albanians was not only to praise this deed, it even inspired anonymous singers and rhapsodists to create popular epics about it.

But Dus Muslia’s memory failed him and he suddenly passed to another song ridiculing the concert of Europe.

“Ublieth Shchépnia pod der ton,

Prédbidate bès pandán,

Perdbidate, poratlia,

Vérish Lluk abban ordij”…“The Albanian people assembled

To conclude a besa,

To reject the tribunals and reforms,

They met at Lluka under the alder trees,

They assembled and took their pleasure,

But the Seven Kings learned about this.

To their feet rose the Seven Kings

And discussed the matter at the Sultan’s royal gate.

‘Look, Sultan, you cannot keep your Albanian land under control.

You cannot raise taxes among them,

We will gladly help you make war,

We will teach you how to hold a country by force.’

Then the sultan gladly rose and assembled

A hundred regiments of his armed men”…At this point, the flow of Homeric productivity subsided and Dus Muslia fell silent.

Time passed but the forest outside was still dark. My thoughts concentrated on the prospect of death. There was nothing frightening in a battle, but being attacked from behind in a narrow gulch, being shot in the chest by a volley of fire without the possibility of defending oneself, this was the ultimate cruelty of the Albanians, to be slaughtered like a lamb for supper, in the midst of the laughs and jokes of the executioners. […]

Finally, that unforgettable night came to an end. Ibrahim returned, no doubt having prepared for our demise in an ambush arranged between Berane and Rugova. We paid the hanxhi what we owned him and mounted our horses. The old vulture came out to say farewell and embraced us hypocritically.

“Albanian highland women of Shllaku, north of the Drin River”

(Photo: Alexandre Baschmakoff, September 1908).We did not refuse the ceremony that took place according to Albanian custom, i.e. right cheek to right cheek and then left cheek to left cheek two times, and not three times as the Russians do. It was a gesture that had no meaning. After that, you could kill one another without infringing at all upon the code of Albanian honour. They have a strange code that is not written down, yet it is strictly observed everywhere. In general terms, the Albanians are completely ignorant of the moral principle of “Thou shalt not kill.” Customary law provides when you may not kill, when you may kill without it being obligatory, and when you must kill. The law is so severe that anyone who ignores it is deprived of all honour in his clan. The code is not based on relations and obligations between men, but on alliances between groups of families. Every man who is killed and must be avenged by his clan becomes a krvina (blood debt). When we were in the upper Lim valley, Zef told me that it was a particularly dangerous spot for him because there were five krvina, obliging the local people to take revenge on his clan. Scores are settled simply. You kill the first man of the other clan that you come across and put him in the score. Each side chops the head off an opponent conscientiously and adds it to the score for his side. Of course, parents seek to avenge their murdered sons. The debt rises once more and continues until the two sides conclude a besa, brought about by arbitrators, in which material compensation closes the muddled account. Payments are not made in cash, but in livestock, grain, textiles or other household goods.

When a murderer is tired of being pursued and wants to rest for a time, he visits the family of the man he has killed. He is safe there as long as he is in their house. They feed him and take care of him for as long as he wants, without making any allusion to him that it is time for him to depart. If he does not realise it is time to go and overstays his welcome, he is reminded at the end of three weeks that he should be on his way. The head of the family then accompanies him to the edge of their clan’s property and says to him: “I am allowing you to depart. Go wherever you want so that we lose track of you. But remember that if I should ever come across you again, I will kill you.”

I would like to add a case that I heard of in Scutari [Shkodra] a few years ago. A man who had killed the four sons of an old woman, arrived at her door and begged to be given something to eat and a place for the night. She let him into the house, but during the night she was unable to control the sorrow and sentiments that welled within her, and slit his throat. When she was taken to court, public opinion in the town was very much against her for having broken sacred custom and they called for her death. The Turkish tribunal endeavoured to lower the sentence and she was condemned to prison for quite a few years. This curious psychology of the Albanians was what obsessed me as we advanced slowly through the rocky and densely wooded gorge in the early hours before sunrise.

Ibrahim and Dus Muslia had attached themselves to our caravan as voluntary guides, the former not leaving my side for a moment and the latter closely following Zef. Their intention was evident. As soon as any shooting began, they would fire and kill us right away.

But we had taken precautions and given orders to the kiraxhi to kill Ibrahim at any sign of attack. Zef found a minute to approach when they could not hear us. His eyes were on fire as he stated solemnly, drawing a little icon from his chest:

“Look at what I have here. It is an icon of the Virgin Mary and a wooden fragment of the cross of Our Lord. I am strong in my Christian convictions and full of force to face battle. I have no fear of death.”

“My dear Zef,” I responded, “I share your sentiments entirely and my heart is full of courage, but I would nonetheless ask you, if I am killed, to take my papers and give them to the Russian Mission in Cetinje so that my travel notes are not lost. They may be useful and I want my relatives to know what happened to me.”

Zef was indignant: “If you are killed by an enemy bullet, I must die with you. I am here to defend you. How could I otherwise ever return to Montenegro?”

I calmed him down. “I have no doubt that you will do your duty. I know that you will fight bravely, but it is probable that all the shots will first be fired at me. Without showing any cowardice, it is possible that you are only wounded while defending me, so do not forget my papers.”

We were then forced to separate as our assassins were swift approaching to hear what we were saying.

It was six in the morning when the çaush (adjutant in command of our escort) stopped at a junction between two trails and, turning to me, said:

“Look, effendi, there are two routes in front of us. The left one leads to Berane and the right one leads to Peja. Which shall we take?”

Zef and I cried out at once: “Hajde do Peća (Off to Peja with us), and let our escort make haste!”

[Excerpt from: Alexandre Baschmakoff, A travers le Monténégro et le pays des Guègues (Saint Petersburg: Imprimérie Russo-Française, 1911), pp. 25-54. Translated from the French by Robert Elsie.]

TOP