| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1912

Sir Robert Graves:

On an Ottoman Mission to the No Man's Land

of European Turkey

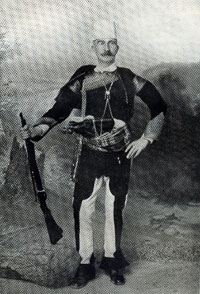

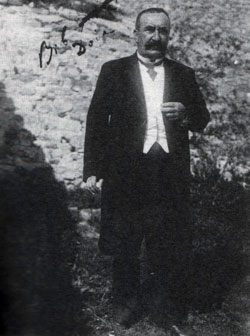

Sir Robert Graves

in Albanian costume,

taken in Shkodra on 29 March 1912.

Sir Robert Windham Graves (1858-1934) was a British career diplomat. He was born in Parknasilla in Ireland and was educated at Marlborough College in Wiltshire. Graves began his career as a student interpreter in Constantinople in 1879 and entered the British foreign consular service soon thereafter, serving for many years in the Ottoman Empire. In 1912 he was a financial advisor to the Turkish Government and in this capacity, from February to May of that year, i.e. during the last months of Ottoman rule in the Balkans, he took part in a Turkish government mission to Kosovo and Albania, which he describes as the "No Man's Land of European Turkey." The following passages, recounting a harrowing journey in a hostile environment, are taken from his memoirs, "Storm Centres of the Near East" (London 1933).

In the meantime the position of the Young Turk Government was growing more and more precarious. The war with Italy dragged on without any hope of an ultimate Turkish victory, and serious disorders had taken place in northern Albania, where military operations under Torgud Shevket and Djavid Pashas had resulted in the temporary repression of a widespread movement of revolt. At the same time it was evident that the Young Turk régime had failed to give satisfaction to the Christian minorities in the European provinces, and there were already indications of the possibility that the Balkan States might unite for the first time for joint action in their favour. It was decided to send a special Mission to Albania and Macedonia, with power to apply urgent remedial measures and make recommendations for the better government of the disturbed provinces. Hadji Adil Bey, the new Minister of the Interior, was placed at the head of this Mission, assisted by Members representing all the important departments of state, and rather to my surprise I was invited to accompany the Mission on behalf of the Ministry of Finance. To this I agreed, after consulting Sir Gerard Lowther and obtaining his approval, and also ascertaining at interviews with Hadji Adil and Nail Beys that I should not confine myself to financial questions only, but be at liberty to express my opinion freely on administrative subjects in general. I found that the only other foreign member of the Mission was to be the French Colonel Foulon, a very capable officer who had been employed with the Gendarmerie all through the period of Macedonian reforms, and who spoke Turkish fluently and was well acquainted with local conditions.

We were to start at very short notice, but my own preparations were very quickly made, as long practice had taught me what was really essential to health and comfort on such expeditions. On the eve of our departure, which was fixed for the 17th of February, I gave a small dance to a few of my younger friends, at which I watched with pleasure the development of a little romance of which I had already had an inkling, and which culminated after my return in a very happy marriage.

Next morning, with my trusty Montenegrin Stepho in attendance, I went to Sirkedji Station and took the train for Salonica, making the acquaintance on the journey of most of the other members of the Mission for the first time. In the light of later history the most outstanding of these was Fevzi Bey, representing the Ministry of War, then a Lieutenant-Colonel on the Staff, who had the reputation of being an expert on the topography of Higher Albania, and now Ghazi Mustafa Kemal's right-hand man and Minister for War of the Turkish Republic. Others were Haidar Bey, a senior Inspector in the Ministry of the Interior, and by birth an Albanian highlander of one of the Malissor tribes on the Montenegrin frontier; Djevdet Bey, a high official of the Ministry of Public Instruction and the licensed jester of the Mission; and Bedi Nouri Bey, who represented no department in particular but seemed to be the agent with the Mission of the Committee of Union and Progress - the power behind the throne. He was always somewhat of a butt for the other members, and a constant target for Djevdet Bey's witticisms. They all received me in the most friendly way, and the good relations thus begun were maintained during the whole of our subsequent association and adventures. Our night in the train was disturbed by noisy demonstrations and deputations at Dedé Aghatch and Gumurdjina, and again in the early morning at Drama.

At Salonica, where Lamb was still Consul-General, we were joined by Colonel Foulon, and after the usual exchange of visits with the civil and military authorities, the work of the Mission began. Interviews with the Vali were followed by some inquiries into the Financial, Judicial and Educational departments, but more attention was given to the state of public security which left much to be desired, and Hadji Adil gave a long hearing in my presence to Colonel Foulon, who told him some home truths, but received no encouragement to his suggestions for the employment of a larger number of foreign Gendarmerie and Police Officers, though the Minister took in good part his vigorous protests against the abuse of the bastinado by Police and Gendarmerie, and promised to take steps for its amendment.

Hadji Adil was then a man of early middle age, amiable and well-mannered and honest according to his lights. Until the Young Turk Revolution he had occupied a secondary post in the Custom House at Salonica, and he owed his rapid rise to the part he had taken in the movement, and the dearth of men of greater administrative knowledge and experience in the ranks of the Committee of Union and Progress. Foulon and I quickly perceived that he was fettered by the rigid lines of policy dictated to him by the Committee, which forbade the acceptance of foreign assistance in positions of authority for the maintenance of law and order, or concessions to the claims of the non-Turkish minorities on any but what they regarded as non-essential points. The equal rights of all Turkish subjects promised by the new-fangled Constitution were to be interpreted, not literally, but only in so far as they did not interfere with the intention of the Central Government to keep the non-Turks in a proper state of subjection, and to discourage and suppress all separatist tendencies. Evidence of this was forthcoming when I brought to the Minister's notice a list which had been communicated to me by the Bulgarian Consul Schopoff of various injustices and disabilities from which the Bulgars of Macedonia were suffering, with suggestions for their remedy or removal. The next day the Vali of Salonica with whom I was on very friendly terms told me that Hadji Adil had shown him Schopoff's Memorandum, and said that, though he thought that the questions raised were very important, he was not able to consider them. Apparently it was thought that the discontented elements could be placated by increased expenditure on education, hospitals, and works of public utility, together with some much-needed improvement in the Administrative, Judicial, and Financial Staffs, and a first step in this tinkering policy was taken at Salonica in the adoption of an extensive programme of road building, of which one-half was to be for economic and the other for obviously strategic purposes.

Horse and carriage in Prishtina

(Photo: Gabriel Louis-Jaray, 1912).

After four busy days during which we inspected schools, hospitals, and Gendarmerie barracks, the Mission pushed on by train to Uskub, breaking the journey for one day for inspections at Kiupruli, where Foulon and I were lodged in a dirty and ill-kept room in the Gendarmerie Office, and had a first taste of the discomforts attending such a journey as that which we had undertaken. At Uskub we found Djavid Pasha, the General in command of the recent operations for the repression of the movement of revolt in Northern Albania, and we heard a not very encouraging account of the existing conditions in the district we were about to traverse. As we were about to leave the Macedonian Vilayets for Albania, I took the opportunity of indulging in some plain speaking with Hadji Adil, and in a long private interview I criticized severely the recent Young Turk policy, especially the new measures which still further restricted the very limited rights of the Christian communities, penalizing their possession of arms for self-defence, while nothing was done to disarm their Moslem neighbours, who were being reinforced by the settlement of lawless refugees from other provinces of the Empire. I again drew his attention to the frequent employment of the bastinado and other cruel methods by the Gendarmerie, whose discipline and efficiency had sadly fallen off since the withdrawal of the foreign officers, and tried to impress on him the folly of rejecting European assistance for reasons of Turkish amour propre. He took all that I had to say in good part and thanked me warmly, but the entry in my diary of that day — "Will it do any good?" — shows that I was not sanguine of the result. I was followed by Foulon, who treated Hadji Adil to a similar heart-to-heart talk on the Gendarmerie question, after which the Minister told me that he had made up his mind to give all the necessary authority to European officers of Gendarmerie, a promise which as will be seen he was never in a position to fulfil.

Mausoleum of Sultan Murad near Prishtina

(Photo: Gabriel Louis-Jaray, 1912).

We went through the usual round of inspections, the exchange of visits with the foreign Consuls, and long and heavy dinners with the Vali, and on the sixth day left early by train, making a slow run through the fine Katchanak gorge in view of the Shar Dagh range to Prishtina. We had now left Macedonia for what was known as Old Serbia, though the Serb element had been largely squeezed out by Albanian immigration. The Serbian Consul who called upon us was naturally pessimistic and incredulous of the good intentions of Hadji Adil, and a painful impression was made upon me when in the course of our inspections we paid a visit to the Serbian school and heard the children shouting Turkish hymns in praise of the Padishah and the (Turkish) Fatherland and Army, while their teachers and clergy looked on with sad and hopeless faces. The Vali of Uskub had accompanied us, and with him we made our inspections and were present at long and desultory discussions of projected improvements in local institutions, in which no practical conclusions ever seemed to be reached.

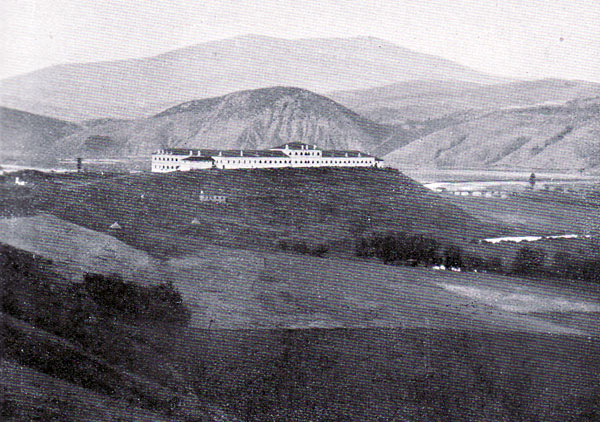

On the morning of the fourth day we drove to the station, passing on the way the Turbe of Sultan Murad Khudavendighiar, erected on the very spot where that monarch was fatally stabbed by the young Serb noble Milosh Kobelitch on the morning of the great Turkish victory of Kossovo in the year 1389, which put an end to the Serbian Empire of Stephan Dushan. The train brought us a little after midday to the terminus of the railway at Mitrovitza, and not much time was lost there in inspecting the Municipality, a good new Secondary School, and fine well-kept barracks where we were received by the Divisional Commander, a soldierly young Colonel who impressed us very favourably. We had now to take to the road, and preparations were made for a very early start next morning, but when Foulon and I arrived at the Government House at half-past six, we found a scene of great confusion and our departure was long delayed. At last we got off in a light victoria followed by my man Stepho with our baggage in another vehicle which we had to hire at the last moment.

The Ottoman military barracks in Mitrovica

(Photo: Ernst Jäckh, 1911).

We were taking the plunge into what was for almost all of us an unknown country, which had very recently been the scene of a savage guerilla warfare, and where the customs and mentality of the Middle Ages had been but little altered by the introduction of the telegraph and modern arms of precision. Our experiences during the next few days were so novel and curious that I have described them in some detail, in the belief that they throw some interesting light on the failure of this last attempt of the Turks to establish their authority over one of their most unruly provinces.

Leaving Mitrovitza and travelling in a south-westerly direction by an execrable road which constantly obliged us to get down and walk, we passed through a fine rolling country, thinly populated and slightly cultivated, with some forest on the mountain range to our right and extensive oak scrub on the foot-hills. We were accompanied by an escort of forty cavalry with flank guards and infantry posts at all the points of danger. The road improved as we emerged into a broad and fertile plain, through which we advanced without incident to arrive before nightfall at the ancient town of Ipek, or Pesh, to give it the old Serb name to which it has now reverted. On arrival we had a vociferous reception from a crowd composed chiefly of schoolboys and children with their teachers, who had been mobilized for the occasion, and Hadji Adil, the Vali, Foulon, and I were lodged with the soldier Governor, Djaffar Taiar Bey, one of three Albanian brothers from Prishtina who played a prominent part in the Young Turk revolution. In his house we were nobly entertained, and though my bed was made up Turkish fashion on a thick mattress on the floor, the sheets were of finest Ipek silk and there was a plentiful supply of hot water for my morning tub, the first I had enjoyed since leaving Salonica. My inda-rubber bath had become an object of interest to some of my travelling companions, whose own ablutions were confined to a visit to the Turkish bath when we reached one of the larger towns, but who seldom failed to inquire politely whether I had been able to get the necessary hot water and privacy.

The activities of the Mission at Ipek differed in some respects from what we had been accustomed to in other seats of government. There were the usual receptions of officials and notables, at which the Christians, whether Albanian or Serb, were noticeably silent and reserved, inspections of schools with evidence of bad teaching in the parrot fashion in which the scholars declaimed set pieces without much understanding of their subjects, and long discussions on Gendarmerie questions in which Foulon was not invited to take part until after he had complained to Hadji Adil of the omission. But in Djaffar Taiar we encountered a new type of Governor, who made no secret of the crying needs of his Sandjak, and in our presence told Hadji Adil that it was men who were wanting in every department, and that unless better Administrative officials, Gendarmerie officers, schoolmasters, doctors and engineers were forthcoming, he despaired of the future of a province which, if well governed and strongly held, would be a bulwark against Serbian, Austrian, and Montenegrin ambitions, instead of being a source of weakness as it then was. Other questions of specially Albanian interest were those of an amnesty for recent political offences, and measures for putting an end to the constant bloodshed caused by observance of the traditional Albanian code, under which blood feud between tribes and families was carried on from one generation to another.

Separate inquiries discreetly conducted by Foulon and myself resulted in some significant revelations. The Gendarmerie Commandant, a Cretan Moslem whose mispronunciation of Turkish made him an object of general derision, was notoriously unfitted for his post, and most of his officers were incompetent and cowardly. We found that a Turkish gendarme whom Foulon had picked out to accompany us as being better than his fellows, had been wounded seven times in ten years' service, and he told us that the force was being recruited from "murderers and tavern loafers", while others admitted that they hardly ever left the shelter of their guard-houses and fortified posts, and that organized patrolling was practically unknown. Serbs and Christian Albanians accused each other mutually of disloyalty to the Turkish Government, the Serbs in particular declaring that the Albanian Catholic clergy were all in Italian pay, but both agreed in expressing themselves as hopeless of any improvement being possible under Turkish rule.

Escorted by two Gendarmes without whom we were informed that it was imprudent to walk abroad, we went up to a fort on the hill which commands a fine view of the town, and to the Catholic church where the priest, a Malissor highlander of most unclerical appearance, was very ironical in his comments on the present good intentions of the Turks. We also walked out to the mouth of the gorge through which flows the Bistritza, a lovely trout stream the sight of which made me regret that I had left my rods and fishing tackle behind in Constantinople, lest their presence coupled with that of my travelling bath and other eccentric belongings should make my Turkish colleagues more convinced than ever of my English lunacy. There we saw the eight hundred-year-old Serb monastery and church of St. Arsen, the seat of the former Patriarchate of Pesh, the only occupants of which were two poorly clad and elderly monks who showed us round and told us how seldom they were cheered by the sight of visitors like ourselves.

It was on the 8th of March that we left Ipek for Diakovo, and it was evident from the extraordinary military precautions taken that Djaffar Taiar had reason to fear for our safety. Our cavalry escort was increased to sixty troopers, and a whole battalion of infantry with some mounted Gendarmes provided flank guards, while we found infantry posted at every point at which a surprise attack or ambuscade might be expected. We started at eight o'clock in drizzling rain which cleared as we advanced through the fine, well-cultivated plain, studded with well-built villages, each of which had one or more stone "Koulas," the fortified dwellings of local notables, the walls of most of which had not been repaired since they had been breached in the course of Djavid Pasha's operations, to render them less defensible and admit of the insertion of windows. We halted for lunch at Istenek, the largest village on the road, in a big "Koula" full of fierce and haggard-looking Albanians, all very attentive and observant of our doings, and manifestly suffering from the humiliation of their forced disarmament. When we pushed on we heard heavy rifle firing in front, and the officer of our escort turned us off the high road, ostensibly to take a short cut across the fields, which soon resulted in our getting badly bogged and being obliged to proceed on foot. Coming to a halt at a very boggy place we met some of our wounded being brought back and heard details of the fighting and repulse with loss of our assailants, and we were then able to resume our journey to Diakovo, where we arrived after dark, some four hours later than had been intended. We were taken for a late dinner to the "Koula" of Riza Bey, a local magnate then in exile at Konia, and afterwards to the "Koula" of one Djemal Bey, a queer-looking old man of seventy-five apparently suffering from senile decay, but who informed us that he was the father of a six-months'-old infant, and who was so anxious to do the honours to his guests that we could only get rid of him by undressing and getting into bed..

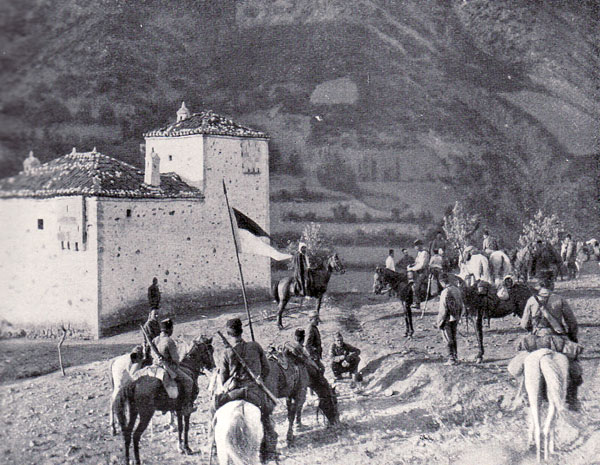

An Albanian kulla

surrounded by Turkish cavallery

(Photo: Ernst Jäckh, 1911).

Next morning on our way to the shabby old Government Konak, we saw the corpses of some of our yesterday's assailants lying in the mud, waiting for someone to remove them, and after the usual interviews went on to a new building which served as the residence and headquarters of the Divisional Commander, with whom we inspected a new military preparatory school installed in the large house of one of the local Beys. A tomb near the yard door marked the spot where just thirty years before the Marshal Mohammed Ali Pasha, who had commanded one of the Turkish armies in the war with Russia, was massacred with the members of his staff in a local revolt, which was suppressed with great severity by the same Mahmud Hamdi Pasha whom I had known so well in 1890 at Adrianople. Then we were taken to the Municipal Office, miserably lodged over one of the few shops in the unpaved main street, and heard complaints of the impossibility of making any improvements with a nominal revenue of only 1200 Turkish pounds, largely in arrears, In the afternoon we wandered about the town, noting the numerous fortified "Koulas" of the wealthier local Beys, and dined again at that of the exiled Riza Bey, whose elder son, whom I find described in my diary as a "cheeky but well-plucked youth", led on one of his henchmen to give us a racy discourse on Arnaut politics from the common man's point of view.

Diakovo was certainly the most primitive, not to say primeval, town in the least civilized of European countries, and I have been unable to find any record of its having been visited and described by any European traveller in modern times. Even Edward Lear in his extensive wanderings in Albania in 1848, so admirably described and illustrated in his Journal of a landscape painter in Albania and Illyria, never ventured so far into the No Man's Land of European Turkey. The place had borne an evil reputation, especially after the murder of Mohammed Ali Pasha, and the local civil and military authorities were much concerned for the safety of our Mission after the audacious attack of the day before. Still larger forces were put in motion at a very early hour in the morning of the 10th of March, including a battery of mountain artillery, and when we met at Riza Bey's "Koula", heavy firing was heard at 7 a.m., and the Turkish colleagues began to look very anxious. Hadji Adil himself did not appear until after eight o'clock, and messengers were constantly coming and going until a brisk artillery fire was followed by the arrival of the excited Civil Governor with news that a "glorious victory" had opened for us the road to Prizrend.

So at nine o'clock we set out, the Minister surrounded by a body of armed and mounted notables, warranted loyal by the authorities, and watched by a curiously undemonstrative native crowd. At a bridge on the outskirts of the town we met eight prisoners being brought in bound, with blows and kicks, and were told that so far the number of casualties was unknown, though we learnt the next day that they had not been numerous, only half-a-dozen Albanians having been killed and fifteen taken prisoners. Our progress was unimpeded save by a bad road with numerous mud holes, and by a fine old Roman bridge the arch of which was so high peaked that our carriages were only hauled over it with difficulty. We lunched off bread and cheese at a Gendarmerie Karakol, and went on to the village of Krusha where we were met by the Governor of Prizrend, Hassan Tossun Bey, and took leave of Djaffar Taiar who, as we heard next day, had another encounter with the rebels on his way back to Ipek.

We entered Prizrend early in the afternoon and were met by a large crowd in a muddy open square, where we had to listen to an address of welcome delivered by a paralytic President of the Municipality, after which we were driven to the Government Konak and lodged in very comfortable quarters by Hassan Tossun Bey, who combined the functions of Civil and Military Governor, and proved a most amiable and attentive host. This was a temporary return to semi-civilization, for Prizrend could boast of some respectable public buildings, barracks, and schools, at least two Consulates, Austrian and Serbian, and the Agencies of one or two Banks. The first function we attended was an official reception by the Minister at the Government Konak of representatives of all the Christian communities and the heads of their respective schools, Greek, Serb, and Catholic. A striking figure was that of the Catholic Archbishop Mieda, a typical Albanian highlander of not more than thirty-five years of age, wearing a heavy cavalry moustache and violet gloves, on whom Foulon and I called later and heard a moving tale of the grievances of his flock, chief among which was the refusal of the authorities to accept the Catholic parish registers as evidence of the date of birth of young men of military age, with the result that two or more sons were taken at once from the same house for service in the army, under the new universal Conscription Law. They had also to complain of the failure of the Government to pay the promised indemnities for the destruction of Catholic properties during the recent disturbances, as well as for the expropriation of Catholic lands and houses required for the construction of new barracks and public buildings.

We were much occupied with the revision of the Administrative, Financial, and Judicial Staffs, in the latter of which sundry dismissals were made not without good cause, and Hadji Adil again found serious fault with the teaching in the Turkish primary and secondary schools. A better impression was produced by the Serbian Normal School for the preparation of schoolmasters and priests, and by the Albanian Catholic school where, however, the Turkish members of the Mission were hardly pleased to find that all instruction was given in the Albanian language, and that the Austrian Emperor's portrait was very much en évidence.

Our spare time during the four days of our stay was fully taken up with seeing the sights of Prizrend, though the last day was spoiled by almost continuous heavy rain. In town we walked more than once through the bazaars in search of the silver ware for which the place was famous, but we found only one surviving master of what has become a lost art, from whom we bought specimens of his beautiful inlaid work. We went to the gorge through which the White Drin flows to the west of the town, and up to a ruined castle on a hill, round and through which we wandered and were shown a bell in an old tower which was said to have been looted from a Christian church in Serres. Coming back, a voluble Greek grocer volunteered to pilot us to the ruins of an ancient Greek church which had been burnt thirty-two years before in a raid of Ljuma tribesmen, and which the community was too poor to rebuild. The general impression was one of decay and ruin, the one more cheerful note being struck when we drove out on a sunny afternoon to a Medressé for Moslem theological students, charmingly situated by the bank of the Drin, and drank coffee in a kiosk surrounded by a well-kept rose garden.

Albanian tribesmen in Kukës

(Photo: Gabriel Louis-Jaray, 1912).

The next stages of our journey were to be taken through a roadless wilderness where wheeled transport of any kind was unknown, so saddle and pack horses were hired, and a showy young half-bred Arab bought to carry the Minister of the Interior with greater dignity. The distribution of our baggage and its loading up on the pack animals was a work of time, and it was not until late on the morning of the 15th of March that we got under way and rode in a south-westerly direction until we left the plain, going on through wooded hills and over a low pass into a grassy valley where we lunched frugally on bread and cheese on the bank of a trout stream near a water mill. We pushed on after lunch until we struck the White Drin whose course we had followed for some time, when several shots from the north bank brought us to a halt in a state of considerable confusion and panic. The officer commanding our escort declared that there was no cause for alarm, and that the shots had been fired by a shepherd who had discharged his revolver as a friendly salute to our caravan, but the muleteers in the rear of our column were positive that they had seen a band of men armed with rifles lurking in the bushes on the north side of the river, and Hassan Tossun, the Governor of Prizrend, who accompanied us as far as the boundary of his province, was evidently much upset by the incident. Advancing slowly and cautiously we reached Kukus at the confluence of the White and the Black Drin, a village most picturesquely situated on a rocky eminence in the fork of the two rivers, and connected with the south bank of the White Drin by a stone causeway. On both sides stretched a fertile alluvial plain, and away to the west towered the snow-clad peak of Koretnik in the Shar Dagh range. We were lodged in the house of Djaffar Agha, a stout and jovial Arnaut, who seemed really glad to welcome us, and when Foulon and I had added a liberal supply of Maggi's soup to the rather thin "chorba" provided by our host, with one or two other little luxuries from our private store, we made a good dinner and spent a cheerful evening with much chaff about the demeanour of some members of the party under fire, until the whole crowd of us were bedded down in the one large room at our disposal.

Up very early next morning, it was eight o'clock before we took the road, and crossing by a ford to the north bank, followed the course of the Drin by a bridle path, where our caravan and its numerous escort could only advance in single file and were strung out to an inordinate length between the river and the steep hill-side, without any possibility of protecting its flanks. About an hour after our start, a volley of rifle fire from the south bank of the river threw our long line into the wildest confusion. Everyone dismounted, and after a moment or two a stampede of horses from the advanced guard of our cavalry escort came down the narrow path, obliging us to step to one side and sweeping away our led horses with them to the rear. I had been riding a few yards behind Hadji Adil and saw his young horse rear straight up on end and deposit his rider on his back in the mud. There was a minute or so of indescribable confusion during which I took such cover as I could find in a small gully between the path and the river, where I was joined by two of our gendarmes. The enemy were ensconced behind some sort of a breastwork at the bottom of a little wooded ravine not two hundred yards distant, from which they kept up a rapid but ill-aimed fire to which our escort replied, apparently with equally small effect. From the path above me I heard the voice of my trusty Stepho who had been with the baggage guard in the rear, and came to look for his master, and when I suggested that he should come down and join me in comparative safety, he said that he had something to do first, and walked on calmly in the open to pick up Hadji Adil from where he was lying and put him in a safer place. He then went on to see what was taking place further up the line, and I afterwards learnt that he had found the officer in command of the escort and suggested that if he sent some of his men to cross the Drin at the Vizir Keupru bridge a little further up, they could turn the enemy's flank and drive them out of their position. Foulon then joined me in my gully and we lighted our pipes and watched the firing, which gradually died down after about a quarter of an hour, when our assailants, seeing their flank threatened, retired up the ravine firing as they went.

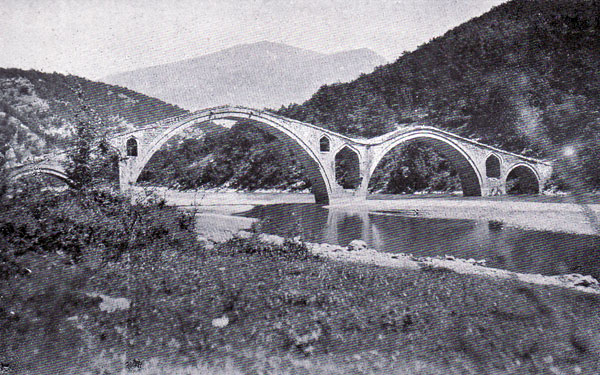

The Vizier's Bridge on the Drin"

(Photo: Ernst Jäckh, 1911).

When some degree of order was restored, and we had recovered our horses, we walked on to the bridge, where we found most of the other members of the Mission holding a council of war in a little fortified post on the top of a hill. After our recent experiences it was decided that it would be too dangerous to follow the course of the Drin all the way to Scutari as had been intended. Accordingly after re-forming our scattered caravan and escort, counting our casualties which were insignificant, and taking leave of Hassan Tossun who had to return with his staff to his duties at Prizrend, we crossed the bridge and made our way through a mountainous region which grew wilder and poorer as we advanced, up and down precipitous hill-sides where girths and saddles slipped, and walking was preferable to riding, until we reached Sakat Khan, a poor and solitary caravanserai on the track leading into the territory of the Mirdites, the largest of the Albanian Catholic clans, who had not taken part in the late revolt against the Turkish Government. It was only two or three days later that we were able to piece together from various sources the truth about the "Battle of Vizir Keupru" as we laughingly called this little adventure. It appears that the attack was organized and led by a former Gendarmerie officer of Ljuma, rejoicing in the name of Ram Razkok, Ram being the familiar Albanian abbreviation for Ramadan. He had taken a prominent part in the late revolt, and had rejected the proffered amnesty unless his personal security and further promotion in the Gendarmerie were guaranteed by the Governor of Prizrend. Hassan Tossun very naturally declined to give any such guarantee, and Ram had taken this opportunity of paying him out by a demonstration of his failure to restore order in his Sandjak.

After a comfortless night in the one crowded room of the Khan and an early breakfast of dry bread and tea, we began another succession of steep ascents and descents through mountains clothed in pine forest above and oak wood below, with flank guards thrown out and every precaution taken to occupy all commanding heights in front as we advanced, until a long upward climb brought us to the pass of Cafa Malk on the border of the Mirdite country. There we were met by one of the Mirdite fighting leaders, Captain Noua Jon, accompanied by the Turkish secretary of Prenk Bib Doda, the hereditary chief of the tribe, and by the Caimakam of the Caza of Puka, who had been warned of our coming. Several hundred Mirdite tribesmen all fully armed and accoutred were drawn up in a line to do us honour, and after the customary salutations had been exchanged we marched down the valley, following the bed of a trout stream, with a double line of tribesmen guarding our flanks and singing a monotonous refrain, until we reached the village of Arsi, where Captain Mark Jon, brother of Noua Jon and principal fighting leader of the tribe, awaited us.

After lunching and watching some indifferent rifle shooting at marks across the valley, Mark Jon, whose fine presence and air of authority marked him out as the real leader of the Mirdites, entertained me with stories of his exile and escape from internment in Asia Minor, and asked if I was not also like himself a "Firari", escaped from exile in Turkey. In the course of the afternoon Prenk Bib Doda arrived with five more companies of Mirdites, each under its tribal banner, and the whole force was drawn up in double line for our inspection. I was surprised to see that a very large percentage, in addition to their rifles and well-filled cartridge belts, carried umbrellas although the day was fine, and I was told that these were men who had returned to their homes after working in Western Europe or America. I could not help wondering whether the umbrella men had been specially mobilized in order to convey an impression of Western contacts and progress to Hadji Adil and his mission. Prenk Bib Doda, who had only lately returned after many years' internment in Asia Minor, was a big dark man of about fifty years of age, too fat to be a good representative of his lean and hardy race, with shifty eyes which almost squinted outwards, and a silly and too frequent laugh, but we found him intelligent and communicative in fairly good Turkish and French. Our conversation had an unpleasant interruption when a shot was heard, and we were told that one of Bib Doda's men had been shot dead by the son of Mustafa Bey, an old Moslem of Scutari who had come to discuss the settlement of a blood feud, but the Mirdites readily admitted that the shooting was accidental and consequently a matter of no importance.

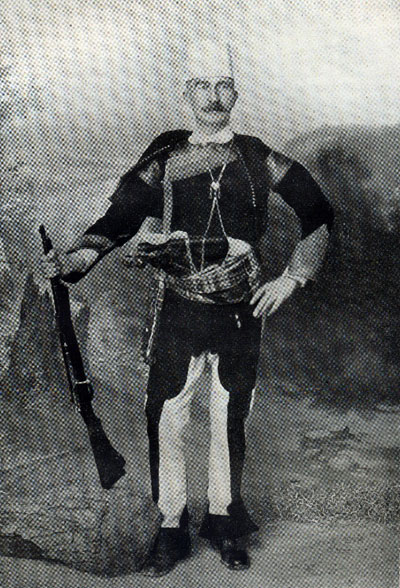

Prenk Bibë Doda (1858-1919).

We had no reason to complain of our night in the Khan at Arsi, and on the morrow we made a short march of three and a half hours, which we covered without being obliged to dismount, to Puka, the seat of Government of the Caza, where the Caimakam provided our meals and we slept in the house of the Judge. Bib Doda had followed us but did not stay the night, as his men were fasting and could get no Lenten fare in a Moslem village. Before dawn next morning we mounted our horses in heavy rain which poured continuously all the morning and prevented us from seeing much of a fine rugged country, our rough and stony road leading ever downwards towards the valley of the Drin. At midday we halted at a small village where the Catholic Corporal of Gendarmerie was presented to us as the husband of five wives, past and present, the survivor being a very handsome Italian type of beauty. Two or three more hours brought us to the ford of the Drin, which was in full flood, but we crossed with only one small mishap when Bedi Nuri, always the unlucky butt of our company, managed to lose his seat and his horse, and scrambled ashore wet to the skin amid the jeers of his fellows. On the far side we were met by the Vali of Scutari, Hairi Pasha, and the Divisional Commander Hassan Riza Bey, who took Hadji Adil into their carriage while I rode his young horse into Scutari, noting as we went how that broad and fertile valley was being ruined by the ravages of the Drin in flood.

Scutari of Albania, or Shkodra, as the Albanians themselves call it, has been so long and so well known to Europeans that I shall not attempt to describe it save by saying that it presented the usual aspect of a Turkish provincial town of about 30,000 inhabitants, the seat of a Governor-General and headquarters of a Division of the Army. The Lake of Scutari, whose overflow is carried down the Boyana to the Adriatic coast near Dulcigno, separates it from Montenegro, and some twenty miles to the north and north-east begins the high mountain range peopled by the five clans of Malissors, mostly Christian, who had joined in the late revolt and had not yet come to terms with the Turkish authorities. We were lodged in the Civilian Club at which we met most of the foreign residents, and we exchanged visits with the civil and military authorities and the Austrian, French, and British Consular representatives, but the Catholic Archbishop Sereggi was unable to return our call as he was confined to the house by a blood feud, his nephew having shot a Moslem youth with whom he had a personal quarrel.

Hadji Adil found himself faced by a very complex situation and quickly decided to get rid of the incompetent Vali, Hairi Pasha, and invest Hassan Riza Bey with civil as well as military authority. The chief problem was to arrive at some terms of settlement with Malissors and Mirdites, the two powerful and warlike Catholic groups whose sole desire was to be left as much as possible to their own devices, without interference by Turkish authorities or truculent Moslem neighbours. Foulon and I did our best to assist him by drawing upon the store of knowledge and experience possessed by the very sensible and well-informed French Consul, Krajewski, and the British honorary Vice-Consul, Summa, the latter a native of Scutari in the closest touch with Catholic circles as well as with local Moslem feeling. Miss Edith Durham, who had been actively engaged in Balkan relief and humanitarian work ever since she had come to Macedonia with the Buxtons in 1903, was up among the Malissors over whom she exercised a remarkable influence, and when she came in to Scutari, she supplied me with information on the subject of their grievances and the urgent need of relief, especially by the supply of maize for the spring sowing before it was too late. We also had several interviews with Bib Doda and with the Mitred Abbot of the Mirdites, Monsignor Primo Docchi, on the course of which the former told us how entirely he distrusted Turkish promises and said that Hadji Adil had better drop all his proposals for schools, road building, the regrouping of the clans, and the enrolment of Mirdites in the Gendarmerie, for the present. Mirdite gendarmes were regarded as spies and traitors and would be killed. His present Lieutenant of Gendarmerie was a Mirdite, "all of whose family, father, uncles, and brothers, we have destroyed, but I keep this man alive. Mark Jon would kill him to-day if I allowed him. We shall see!" The Mirdites did not like priests to mix in secular matters, and he did not wish the Government to pay them or make them grants of money, no doubt lest they should be detached from their allegiance to himself, and he told us how he had latterly burnt a priest's house for some offence, that being the customary local punishment. All he asked was that they should be left to themselves, failing which he mentioned a scheme for his migration to Bosnia with 60,000 of his people, which he had put aside for the present as being trop scandaleux.

Edith Durham on relief work

in northern Albania.

The gist of these conversations we conveyed to Hadji Adil, of course suppressing whatever might have injured our informants, and the Minister interviewed the Consuls and took note of their suggestions, after which in conjunction with Hassan Riza he drew up a series of proposals intended to conciliate both Malissors and Mirdites, but as far as the latter were concerned these proved so utterly inacceptable that, when they were communicated to Bib Doda, he at once resigned the post to which he had just been appointed as Reorganizer of Mirditia with the title of Prenk Pasha, declaring that his people would fight rather than accept, and that he could neither stop them nor remain in office if they fought. As for the Christian Malissors, they would take all they could get from the Turks and give nothing in exchange, and their attitude towards Turkish authorities and Moslem fellow-subjects was well exemplified not long before our coming when, a Catholic Church in the outskirts of Scutari having been desecrated by Moslems of the town, a strong raiding party of Malissors came down by night, captured and burnt a Turkish guard-house with its inmates, and killed a pig in a neighbouring Mosque before returning unopposed to their mountains.

School, financial, and Gendarmerie inspections had become of minor importance in this threatening atmosphere, and were hurried through in a rather perfunctory fashion, to enable us to take the road again on the tenth day after our arrival. Before leaving Scutari, Foulon and I, at the request of our Albanian colleague Haidar, were photographed in Albanian dress, Foulon in the magnificent ceremonial robes of Bib Doda, so heavily overlaid with gold, gems, and embroidery, that they were said to weigh seventy pounds, and I in the ordinary costume of a Scutari Moslem Bey. We rode out on the morning of the 30th of March with our usual military escort, and a guard of honour of armed and mounted Shkodra notables, who turned back to town from the village where we halted for lunch. We followed the high road to Shin Djin, that being the characteristic Albanian abbreviation for San Giovanni di Medua, passing through a fertile and well-cultivated district with hedgerows and orchards, seeing the first olive trees and pomegranates, to arrive before nightfall at Lesh, the short for Alessio, a village at the foot of a fine old medieval fortress from which we had a splendid view of the Adriatic coast, from San Giovanni di Medua up to Dulcigno to the north, and down to Cape Rodoni to the south. Next day we pushed on in heavy rain by a villainous road in which the remains of an old paved causeway alternated with deep mud, and through thick jungle in which we saw many signs of wild boar, to reach the Mat river before noon, where the notorious Essad Pasha Topdan of Durazzo was waiting for us with a large armed following. We were ferried over in two dugouts lashed together, while our horses had to swim behind, the whole operation lasting more than two hours.

Essad Pasha Toptani (1863-1920).

We were now in Essad's own country, in which as head of the powerful Topdan family he reigned supreme, and almost gave himself the airs of a sovereign prince. He assumed charge of our party and conducted us, again through deep mud, to the village of Guenem, where we were to spend the night, and where the Caimakam and notables of Croia came to pay their respects. The rain had ceased and the sun came out, giving us a glorious view of the old fortress of Croia, Skander Beg's famous stronghold, with its towers and minarets outlined against the sky in the setting sun. We could not get rid of Essad, who quartered himself in the house in which Hadji Adil, Foulon, and I were lodged, and kept us waiting until ten o'clock for our evening meal while he held forth chiefly on his own importance and the failure of the Young Turks to recognize his merits, but during Hadji Adil's occasional absences he gave us to understand how cordially he detested and feared the new regime in Turkey, whose programme if carried out would put an end to his privileged position and oblige him to fly the country.

It would be hard to exaggerate the beauty of the country through which we rode next morning, a land of mountain, oak forest, and crystal streams, halting at noon at Derven, where in the garden of the Bektashi Dervishes' Tekke we were shown a cedar tree the trunk of which five of us could barely span. There we were met by Essad's carriage, in which I drove with him and Hadji Adil to Tirana, now the capital of independent Albania, and after the inevitable official reception and parade of school-children, the Minister and I were lodged in the Government Konak, and spent a quiet evening alone together. Hadji Adil then told me what I knew already, namely that Essad had come to make the best bargain he could for himself, and that he was prepared to give his support to the Young Turk Government in the General Election which was then in progress, and help them to defeat their most formidable adversary Ismail Kemal Bey, the leader of Albanian Nationalism in the south, in exchange for a lucrative post in the War Ministry at Constantinople, and non-interference in his own sphere of influence. The bargaining continued long enough to delay our departure until the next day, and after lunch Hadji Adil came and told me privately that they had come to terms, and that Essad would go to Constantinople as member of a Commission at the War Office, and would then resign the seat in the Chamber to which he had just been elected as Deputy for Durazzo. In the afternoon we inspected the schools, the best which we had seen so far, and walked about the town admiring its broad paved streets and the bazaars with new one-storied buildings and colonnades, all very superior to anything we had seen in the course of our Albanian travels.

Early postcard view

of the colonnades of Tirana.

It was raining when we started early next morning, but there were occasional breaks and, riding nearly due south, we mounted slowly through woodland full of wild olive, arbutus, and myrtle, and down to the ford of the river Arsen, where the unfortunate Bedi Nouri again lost his head and seat in mid-stream and was rescued by Essad Pasha in person. The weather cleared in the afternoon, and after a stiff climb to the pass over the Gabé range and down a steep descent on foot, we met at the top of another lower ridge the Governor and notables of Elbassan, with a company of Laz infantry who escorted us into their town with the usual tiresome formalities.

The General Election was taking place when we reached Elbassan, and we learnt next morning that a rich Albanian Bey who was not a supporter of the Government was leading at the poll and was likely to be elected. Hadji Adil deciphered in my presence a telegram from Constantinople stating that the Minister for War was all for breaking Essad Pasha's power, but that the Government awaited his decision, which he told me was to temporize in view of the evident strength of the Albanian Separatist movement, and the danger of driving so powerful a local chief as Essad into open opposition. So Essad went on to Constantinople to take up his post at the War Ministry, and we spent two days in Elbassan during which Foulon and I explored the town with its picturesque surroundings, and made our own inquiries into the political situation. What we gathered from independent and unofficial sources showed that we had got away from the region of dangerous nationalism and foreign propaganda in the north, and that here at least there was no immediate danger of trouble, if the Government would refrain from applying the new and onerous laws for universal conscription and the increase of the direct taxes.

Leaving Elbassan on the third day, we crossed the Shkumbi river and rode due south by a bad road, with one little adventure when the horse of one of our party went over the edge of a deep ravine, nearly dragging its rider with it, and breaking its back in the fall. Four hours brought us to the Devol river, which owing to a stupid mistake of our Gendarmerie escort, we crossed with difficulty at the wrong place. A better road mounting gradually through wooded hills brought us to the top of a pass from which we had a magnificent all-round view of the plain of Elbassan and the valleys of the Shkumbi and the Devol, with the snowy peak of Timurika nearly 8000 feet high, away to the south. When we reached a small village in the evening we found that our guides were again at fault, and this was not Ghegalar where we were to have spent the night, but Polovin, a wretched hamlet in which the only accommodation was in one room with a large hole in the roof to let the smoke escape. Our baggage animals which had crossed the Devol at the right ford had gone to Ghegalar, and it was too late to follow them there, so after a scrappy meal which the resourceful Haidar managed to cook for us, we settled down to a most comfortless night on the floor, with no covering but a couple of rugs of doubtful cleanliness and our saddle-bags for pillows, our rest being continually broken by the impossibility of keeping warm, choking smoke, and villainous smells from the primitive sanitary arrangements of our lodging. There was no inducement to prolong our stay in the morning, and as soon as we had rejoined our baggage train which came to meet us half-way, we hurried down the south side of the pass and through the plain as fast as we could go into Berat, being met by the Acting-Governor with a group of well-mounted Berat Beys. As we rode into the town we got the best view of it from the old bridge which spans the Osum river, with the splendid old castle looking down from the height above and the snowy range of Timurika in the background.

Only one day was given to Berat, during which Hadji Adil was much preoccupied with the unsatisfactory condition of the Gendarmerie, and the result of the elections, as it was impossible to find Government candidates with any chance of success, and it was thought best to let the local Beys fight it out among themselves. That day our muleteers came to complain that they were the victims of "zulm", i.e. oppression, in that they were compelled to carry our baggage through these mountainous regions at a rate of pay which did not nearly cover their expenses, while they had lost more than one animal through accident, and the others were losing condition sadly. I told Haidar and Hadji Adil of their grievances, which were quickly redressed, and our caravan took the road next morning in better spirits, with the thought that we had got over the worst of our difficulties and would soon be again in a country of wheeled transport. Our road southward rose gradually through wooded hills full of arbutus and myrtle, until we struck the old Berat-Janina high road, now completely abandoned, and reached the top of the pass crossing the Malakastra range, after which we made a short cut to the right to reach a ruined Khan and the Bektashi Tekké of Glava where we passed the night.

Leaving Glava, it was our intention to make our next halt at Tepeleni, the home of the celebrated Ali Pasha who played so large a part in the history of European Turkey in the early years of the nineteenth century. We walked and rode alternately in heavy rain and mist, always descending steeply until we reached the foot of the pass, and then followed the valley of the Viosa, when the weather cleared in the early afternoon, and we struck the river nearly opposite Tepeleni after negotiating two or three very dangerous passages, where only a few inches of slippery pathway remained between a rocky wall on the left and a sheer drop of fifty or sixty feet to the river on the right. The Viosa was in full flood and the ferry boat had been abandoned, making it impossible to cross, so we pushed on to the neighbouring village of Dragot and there passed another comfortless night. In the morning it was tantalizing to see Ali Pasha's fortress just across the water, but there was no alternative but to follow the north bank through Klissura to the bridge some twenty-five miles up-stream from our starting point, and then turn back to Premeti for the night. This was the seat of government of a Caza, to which we were glad to have paid this unexpected visit, for the Caimakam was able to present a useful report on the needs of his much-neglected district.

We had now come to the last stage of our long riding journey, as our objective was the comparatively civilized town of Arghyrocastro, when we should find a carriage road to Janina, but to reach which we had a trying day's march before us, including the crossing of a high mountain pass by a notoriously bad road which our caravan would be the first to take that spring. Making an early start, we began to ascend almost as soon as we left Premeti, and for two hours and a half we plodded on upwards with snow beginning to fall until we reached the top of the Tumbal pass, over 5000 feet above sea level, and met a furious blizzard with driving snow in our faces, which reminded me of an Erzerum "tipi". We made the greater part of the descent on foot, and then encountered a succession of steep ridges and furrows, in which we had another example of bad staff work on the part of our escort, which took a wrong turn without noticing that we had not followed its example, and left our precious Mission for three hours with one solitary Gendarme as guide and escort until they overtook us with many apologies and excuses. At length in the late afternoon we reached the top of the last ridge where we looked down across the plain to Arghyrocastro, and were met by the Governor and a small staff with whom we rode steadily on, crossing the river Zrinos, an affluent of the Viosa, by a stone bridge, and striking the Janina-Arghyrocastro carriage road not long before reaching the town. On the outskirts a company of infantry was drawn up at a Karakol with buglers who at the moment of our passage blew a sudden and discordant blast, terrifying our horses and nearly driving my mount off the road into a deep ravine on the right. One of his legs was already over the edge and I was about to throw myself off, when the ever-ready Haidar who was nearest me managed to seize the reins and drag us back to safety. We had ridden and walked about thirteen hours almost without a halt and had left our pack-train behind, but most of them turned up two hours later, having lost one horse killed by a fall over a precipice, and four more left behind, lamed or otherwise broken down.

At Arghyrocastro we were confronted with a new problem in the rival propaganda of Greeks and Albanians, which found its chief manifestations in educational questions, the Albanians claiming that their language and the Latin alphabet should be made obligatory in their schools, which the Greek clergy forbade their children to attend. These quarrels and the usual inspections occupied the Mission for one day, and after two good nights' rest in comfortable quarters, Hadji Adil and I took seats in the best of half a dozen carriages which had been brought from Janina for our use. The road was in good order and we could easily have reached Janina by evening, but we were delayed by having to receive deputations from the numerous large Greek villages along the road, when priests and schoolmasters read long speeches in which they expressed their loyalty to the Empire, their gratitude to the first Constitutional Minister to visit them, and their hopes for attention to their many needs, more especially in the establishment of public security, in terms so identical that they were clearly dictated from a common source. For some unexplained reason we stopped before nightfall at a miserable roadside Khan, where no preparations had been made for our reception, and we passed a comfortless and almost sleepless night, Hadji Adil, Foulon and I being doubled up in one small and dirty room with a single bedstead for the Minister, while our unfortunate servants spent the night without food or a decent shelter. Hadji Adil was obliged to admit to us that the failure of the Janina authorities to make any arrangements for his comfort and ours was typical of Turkish bungling and administrative incapacity, and he did not fail to point the moral when we met the Vali next morning.

Driving on by a good road with new stone bridges and "cantonniers'" huts every ten kilometres, we were met by the Vali of Janina, Mehmed Ali Bey, and the Divisional Commander, Essad Pasha, whom I had known and liked at Salonica, and whose carriage I shared for the drive into the city. Crowds of people in carriages, on horseback and on bicycles came out to greet us, and for the last two or three miles a Committee of Union and Progress band in uniform played us into town at a foot pace. This was by far the most brilliant reception in the experience of the Mission, the garrison being turned out for a full-dress parade of troops, the shops all shut up, houses flagged and Consular flags hoisted, while large crowds followed us through the streets to the Konak, where an official reception and speech-making awaited us. We were well lodged at a good hotel in European style, with modern sanitary arrangements which were very welcome after our recent experiences, and after paying one or two visits on friends in the Consular Corps, we were entertained at a banquet in the Town Hall.

We found ourselves in an entirely different atmosphere from anything we had met in Turkey, most different from the medieval conditions in which we had lived for the past six weeks. Here the Greek language, culture, and enterprise predominated to such an extent that the Turkish educational propaganda of the Committee of Union and Progress, the Jewish schools, and the Roumanian Commercial School intended to foster the Vlach element, were quite unable to compete with the well-equipped and endowed Greek schools, whose classes were attended by numbers of non-Greeks eager to profit by the superior advantages which they offered. Optimists might imagine that the Greeks of Janina could be won over by conciliatory measures and minor concessions, but very little contact with their leaders convinced me that union with the Greek kingdom was their sole ideal, and in their dealings with the Mission they attached far more importance to economic measures such as better communications and commercial facilities, than to any improvement in their political status under Turkish rule.

Our nine days in Janina were chiefly occupied with the discussion of economic and social questions, such as road building, public security, the improvement of the situation of the peasantry by the breaking-up of large and ill managed estates and their distribution among the cultivators, and the reform of the Tithe Law, but we had also to endure a round of tedious entertainments, dining out every night with the Civil, Military, Municipal, and Educational authorities, and listening to lengthy orations of more than doubtful sincerity. My pleasantest recollection is of repeated visits to the house of Essad Pasha, the Divisional Commander, himself the head of an old Janina family with a good tradition of friendly relations with their Christian neighbours, and remarkable for his high character and liberal views - in all respects the antithesis of his namesake, Essad Pasha Topdan, the unscrupulous semi-savage who had accompanied us from the Mat river to Elbassan. Not many months were to pass before he was besieged in Janina by the Greek Army in the first Balkan War, and obliged to surrender after a gallant defence, and three years later found him in command of a Turkish Army Corps at the Dardanelles, where he proved himself a chivalrous adversary. We had little time for sight-seeing but the day before our departure Foulon and I managed to visit the citadel and the island in the lake where Ali Pasha was treacherously murdered by his enemies, and then drove round the town and into the country on the road by which we came, to see the great plane tree on which Ali was accustomed to hang all those who disputed his authority.

When we left Janina on the 23rd of April by carriage for the north, I hoped that we had seen the end of our horseback journeys, but after we had driven two hours the carriage road came to a sudden end and we had to take again to the saddle. On we rode, climbing steeply to the prosperous Greek village of Zagor, and then through a picturesque valley with extraordinary limestone formations, across the head waters of the Viosa, and up to Monodendron before dark. There we spent the night, and rode on next morning for three or four hours through broken country to Columvaki, to find ourselves again at the beginning of a high road, with carriages waiting to take us on to Leskovitz by evening. Bright cool weather and beautiful scenery inspired Hadji Adil and myself to walk most of the next morning, up hill and down dale and taking frequent short cuts, with the snowy pine-clad Grammos range on our right. After we had lunched at the bridge of Shilaz, the weather showed signs of breaking, and we took to the carriage again, to arrive in the rain at Hertzeg, the capital of the Colonia Caza, for the night. Another day's drive in cold and rainy weather through a stony and treeless hill country, thinly inhabited and with few signs of cultivation, brought us to Koritza, which had lately become the capital of a Vilayet owing to its growing importance as a commercial and educational centre, and a battleground of Greek and Albanian propaganda. At Koritza we spent two days in good quarters supplied by the newly elected deputy for the town, and the Minister was kept very busy by the energetic Vali, Ali Munif Bey, who was not destined to see any of his suggestions carried out, as his province ceased to be Turkish within a few months. At the American School for Albanian girls founded some twenty years before, I heard from Mr. and Mrs. Kennedy a full account of the difficulties and disabilities under which they laboured, which I brought to the Minister's notice and obtained his promise of redress. Arrangements were now made for sending our heavy baggage to Monastir, while we were to cross the Lake of Ochrida and pay a short visit to Dibra before saying good-bye to Albania, and on the third morning we set out very early, crossing the head waters of the Devol, skirting the west shore of the small Malik lake, and on through level country to Starovo, where we were to embark for our voyage across the Lake of Ochrida.

This was our only experience of the kind during our wanderings, and as such deserves a few lines of more detailed description. On a large boat painted a bright blue a temporary platform had been laid amidships for the accommodation of eleven of us, just leaving room for six oarsmen in the bows and the skipper with a steering oar in the stern. The wind rose soon after we started, and the boats carrying the rest of our party were quickly lost to view in the mist. As the lake grew rougher, Hadji Adil was very seasick, and our skipper, a drunken Bulgar, never ceased loudly shouting encouragement to his crew, and assuring us that he himself was a first-rate "capitan" until the Gendarmerie Colonel who accompanied us threatened to tie him up, when he promptly replied, "If you do, you will never come to land." However, in spite of rain, cold, and rough sea we managed to keep cheerful, and made the little port of Ochrida at the north end after six or seven hours' steady rowing, just as the sun was setting. We were taken to the house of the Young Turk leader, Eyub Sabri Bey and turned in almost immediately after dinner, to be awakened after midnight by the arrival of Foulon, who had taken passage in another boat, the crew of which had refused to cross the lake and had landed him and his companions at the Monastery of Sveti Naum, on the south-west shore, from which it had taken them six hours to ride into Ochrida. There was nothing to detain us there and we rode off next morning early by a very bad road for Dibra, seeing many signs of the fishing industry for which the lake is famous, in fish pens and basket traps along the shore, and I remembered having seen numbers of the great lake trout being brought in frozen to Sofia in winter time some thirty years before. The Drin flowing out of the lake was fairly clear in colour and seemed full of trout, and we followed its western bank through marsh land past Struga until we left the plain, and mounting gradually through fine rocky gorges with cliffs a thousand feet high overhanging the road, reached the bridge of Ispila over the Drin in the early afternoon. The arch of this bridge was so high pitched that our carriages had to be pushed over it by man power, and on the far side we found the Dibra authorities and notables ready to escort us into town, where mails were awaiting us bringing the tragic news of the loss of the Titanic.

At Dibra with its essentially Albanian population we heard outspoken complaints by the Opposition candidates of flagrant interference by the Gendarmerie in the freedom of the elections, and when the Minister advised them to apply for redress to the Law Courts, I found it difficult to keep my countenance, well knowing what the inevitable result would be. There was also intense rivalry between the Bulgar and Serb minorities, chiefly over religious questions such as the custody of certain Orthodox Churches, and the right of the Bulgarian Bishop's representative to sit on the Administrative Council, and their charges and counter charges were met by Hadji Adil with the assurance that these matters would be treated at Constantinople between the Bulgarian Exarch and the Ministry, when he had no doubt that justice would be done. The day after our arrival I felt the first symptoms of a sharp attack of influenza. We were lodged in the large and comfortable house of Fuad Bey, son of the late Ismail Pasha of Dibra, who had amassed a large fortune as a Government contractor, and when I was obliged to take to my bed, our host and the invaluable Haidar took such good care of me that after three or four days I was sufficiently recovered to join the rest of the Mission at Ochrida, whither they had returned the day before.

Information had been received that an attempt was to be made by Bulgar Comitadjis to blow us up at a bridge on the Resna road an our way from Ochrida, and our departure was delayed next morning until the Police had investigated the matter. They found and brought in two iron bombs with detonators and a large quantity of dynamite which had been concealed under the bridge, and connected with a hiding place some five hundred yards distant by a cord, a pull on which would have treated a contact between two electric piles and exploded the charge. Starting late, we inspected the scene of the intended outrage, and pushed on to Resna town, where we spent the night in the house of Niazi Bey, the officer who shared with Enver Bey the credit of starting the Young Turk Revolution by taking to the hills with a small following of soldiers and malcontents in 1908, and on the 8th of May a short day's drive took us through the plain of Resna and over the pass leading to the plain of Monastir, with the Peristeri mountain 8000 feet high on our right, to be met by a crowd of officers and notables who offered us lunch at a Gendarmerie Karakol, and escorted us into town in state, not sorry to have reached the end of our rough cross-country journeyings, and to see such signs of modern methods of transport as a railway line and even a few motor cars.

The konak of Monastir (Bitola).

Not much time was given us to rest from our fatigues during the eight days of our stay in Monastir, for we had got back into the thick of the Macedonian question with its Bulgarian, Serb, and Greek cross-currents, complaints on all sides of interference with the freedom of the elections, and the difficulty of applying the new administrative and financial measures. Nor had we yet escaped from the tangle of Albanian affairs, for news came of fresh trouble in Ipek, where Djaffar Taiar had been obliged to take serious military measures, including the use of artillery, for the maintenance of order and the protection of the workers on the new military roads, and the Minister sent off Fevzi Bey to observe and report on the situation there. At the British Consulate I was glad to find Morgan, one of the best of our younger Consular officers, and in Ibrahim Fethi Pasha, the General commanding the Army Corps, I renewed acquaintance with an old friend whom I had known more than twenty years earlier in Bulgaria, where he had been on the staff of the Turkish Commission. It was he who had then delighted me by describing his father, a very stout General Officer, a "très bel homme, il est pour ainsi dire, cube", meaning that he was as broad as he was long, a figure much admired by old-fashioned Turks. Long discussions of the new Tithe Law, and inspections of Government departments and schools alternated with official dinners and luncheons, but one day was devoted to a flying visit by motor car to Perlepé, an important town halfway between Monastir and Kiupruli, in the endeavour to adjust a long-standing dispute between the Bulgar and Serb communities for the possession of a monastery.

It was Hadji Adil's intention to break our journey to Salonica in order to visit two or three of the southern Cazas of the Monastir Vilayet, so we took the morning train on the 17th of May as far as Sorovitch, whence we drove through a rather monotonous rolling country with Mount Olympus visible to the south-east, to Kozana where after a rapid inspection we spent the night in the house of a rich Greek banker, and on the two following days visited Serfidjé and Kayalar, returning to Sorovitch to catch a special train which brought us to Salonica an the 20th of May, almost three months from the day on which we had started an our wanderings.

Much uneasiness had been caused by the renewed disturbances near Ipek, but Fevzi Bey reported that not more than 700 insurgents had been on foot, and that they had been dispersed with a loss to the Turkish troops of thirteen killed and thirty or forty wounded, and that was the last we heard of Albania for the time being. To my surprise I found that Hussein Kiazim Bey, the Young Turk Vali of Salonica, and Azmi Bey, the Mutessarif of Serres, were taking a very strong line on the subject of Gendarmerie abuses, and especially the illegal use of the bastinado, to which their attention had been drawn by the Bulgarian Consul Schopoff. At several interviews with the Minister these two insisted strongly on the dismissal and punishment of the most notorious offenders among the officers, and on one occasion I had even to calm Hussein Kiazim down and keep the peace between him and Hadji Adil, who ended by promising him satisfaction. Two days later at the Government Konak, the Vali in my presence handed to the Dragoman of the Bulgarian Consulate a list of twelve Gendarmerie officers who had been dismissed and sent for trial, asking him to convey his thanks to Schopoff for his information. This, like other remedial measures, came too late to influence the course of events, and Schopoff told me that he no longer believed that any such palliatives could avert the impending catastrophe. The week we had to spend in Salonica was enlivened for me by the hospitalities of the Lambs, the Foulons and Crawford Price, who was acting as the representative of The Times, and I was naturally interested to see articles in the Constantinople Turkish press suggesting the appointment of an European adviser to the Ministry of the Interior, in one of which my name was mentioned as the most probable candidate.

Although the province of Adrianople was outside the scope of his Mission, Hadji Adil as Minister of the Interior wished to visit its capital before returning to Constantinople, and accordingly we left Salonica by train on the morning of the 26th of May, and after receptions at Drama and Xanthi, where we were met by the Vali of Adrianople, we reached Karaghatch station early next day, and were driven in great pomp by a good macadamised road into town, seeing much evidence of improvements effected since I had been Acting Consul there more than twenty years before. In addition to a fine new Town Hall, we were taken to see two new mixed Primary Schools, well housed and equipped, a new Model Rushdiyé school in the Christian quarter, intended to attract Christian pupils, a Secondary Gymnasium with over two hundred boarders, good dormitories and class rooms and a physical laboratory, and a Technical School of Arts and Crafts, while a Normal School for the training of school teachers was in course of construction. It is sad to think that within a very few months most of these signs of progress were to be wiped out in the long siege and bombardment of the city by the Bulgarian Army in the Balkan War. After a reception of the Consular Corps, I exchanged calls with our Consul, Major Samson, from whom I received much enlightenment on the situation in his district, and we visited the great Mosque of Sultan Selim, and took a motor drive to the bridge over the Arda, and along the Ortakeui road, returning to town via Sinekli Su and another road.

It was during our short stay in Adrianople that Hadji Adil told me privately that the Scutari authorities, jealous of Miss Durham's extraordinary influence over the still recalcitrant Malissors, had recommended her expulsion, and asked for my advice on the subject. I very strongly dissuaded him from any such foolish action, assuring him that Miss Durham's influence was entirely due to her unselfish and untiring efforts for the relief of suffering humanity, and that her expulsion could only have the most disastrous effect, not only locally, but also upon public opinion in England.

Our return to Constantinople was a cause of rejoicing to everyone connected with the Mission, some of the members of which had spent practically all their lives in the capital, and were quite unaccustomed to such fatigue and privation as we sometimes had had to endure. They were all very merry when we boarded the night train a little before midnight, and I saw two or three of the younger ones actually dancing for joy in the corridor of our reserved sleeping car. When I rose in the morning, I found in our saloon car Talaat Bey who had come to meet us half way, and on reaching Constantinople at 8 a.m. I was met by my nephew Philip, took a quite affectionate leave of Hadji Adil and the rest of the staff, and drove home to enjoy the luxury of a real hot bath of which I had been so often deprived during the past months.

[extract from: Sir Robert Graves, Storm Centres of the Near East: Personal Memories, 1879-1929 (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1933), p, 253-277.]

TOP