| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

![]()

Leo Trotsky, ca. 1917

1912

Leo Trotsky:

Behind the Curtains of the Balkan WarsLeo Trotsky (1879-1940) was a Russian revolutionary and a major figure of the October Revolution of 1917, second only to Lenin. He was later founder and commander of the Red Army and People’s Commissar for War, but, under Stalin, was expelled from the Communist Party and deported from the Soviet Union in 1928. Trotsky was eventually assassinated in Mexico by an agent of Stalin. His ideas formed the basis of Trotskyism, a major school of Marxist thought.

Long before the Russian revolution, in September 1912, Trotsky was sent to the Balkans by the Kiev newspaper “Kievskaya Misl” as a war correspondent to cover the Balkan Wars in Serbia, Bulgaria and Romania. The following is one of the articles Trotsky sent back to his newspaper, a report on the atrocities committed against the Albanians of Macedonia and Kosova in the wake of the Serb invasion of October 1912.

This is what one of my Serbian friends told me. I wrote it down almost word for word.

“During the war, I had an opportunity - whether it was a good one or a bad one is hard to say – to visit Skopje (Üsküb) a few days after the Battle of Kumanovo. In view of the nervousness caused in Belgrade by my request for a laissez-passer and the artificial obstacles put in my way at the War Ministry, I began to suspect that those in charge of military events did not have a clear conscience and that things were probably happening down there that were hardly in keeping with the official truths released in government communiqués. This impression, or rather foreboding, grew when I happened to meet an officer in a train in Niš, who was travelling to Skopje with orders for the General Staff. This officer was a good and honest fellow whom I had known for some time. The moment he learned that I was destined for Skopje and had received permission to go there, he reacted with open hostility, claiming that there was no reason for anyone to go to Skopje who had no business there and that authorities in Belgrade had no idea what harm they were doing by allowing unauthorized persons to travel there, etc., etc. In Vranje, on the Serbian border, realizing that I did not intend to be dissuaded by him, he changed his tone and began to prepare me in great detail for what I would see in Skopje. ‘It is all terribly unpleasant, but is unavoidable.’ And of course in his description of the events, my friend did not forget to mention the government policies behind them. I must admit that it made me all the more suspicious. I mean that the atrocities, a vague echo of which had seeped through to Belgrade, could be no coincidence, isolated cases or exceptions, if a high-ranking officer was explaining them as part of ‘government policies.’ There was obviously intention involved. But whose intention? The military authorities? Or the government? I soon received an answer to this question when I arrived in Skopje.

Old postcard of Skopje train station.

The atrocities began as soon as we crossed the old Serbian border. We were approaching Kumanovo at about five P.M. The sun had just set and it was growing dark. But the darker it became, the stronger was the contrast with the terrible blazes that illuminated the sky. There were fires everywhere. Whole Albanian villages had been transformed into columns of flames – in the distance, nearby, and even right along the railway line. This was my first, real, authentic view of war, of the merciless mutual slaughter of human beings. Homes were burning. People’s possessions handed down to them by their fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers were going up in smoke. The bonfires repeated themselves monotonously all the way to Skopje. We arrived at ten at night. I clambered out of the cattle car I had been travelling in. The whole town was deathly silent. There was not a soul out on the streets. Right in front of the train station, there was a group of soldiers making drunken noises. All those who had arrived by train disappeared in the dark and I soon found myself alone at the station. Four soldiers held their bayonets in readiness and in their midst stood two young Albanians with their white felt caps on their heads. A drunken sergeant – a komitadji – was holding a kama (a Macedonian dagger) in one hand and a bottle of cognac in the other. The sergeant ordered: ‘On your knees!’ (The petrified Albanians fell to their knees. ‘To your feet!’ They stood up. This was repeated several times. Then the sergeant, threatening and cursing, put the dagger to the necks and chests of his victims and forced them to drink some cognac, and then… he kissed them. Drunk with power, cognac and blood, he was having fun, playing with them as a cat would with mice. The same gestures and the same psychology behind them. The other three soldiers, who were not drunk, stood by and took care that the Albanians did not escape or try to resist, so that the sergeant could enjoy his moment of rapture. ‘They’re Albanians,’ said one of the soldiers to me dispassionately. ‘Hell soon put them out of their misery.’

Terrified, I fled from the group. It would have been to no avail, had I tried to protect the Albanians. It would have been enough for the soldiers and the sergeant to confiscate the Albanians’ weapons… And all this was happening right in front of the train station where my train had just arrived. I was horrified and ran away so that I would not have to hear the screams of pain or help…

A deathly silence reigned in the town, or more exactly, on the streets. All the gates and entrances were always closed at six P.M. But the komitadjis began their work the moment it grew dark. They broke into Turkish and Albanian homes and did the same thing, time and again: stole and slaughtered. Skopje has 60,000 inhabitants, half of whom are Albanians and Turks. Some of them had fled, but most of there were still there. And they were now victims to the nightly bloodbaths.

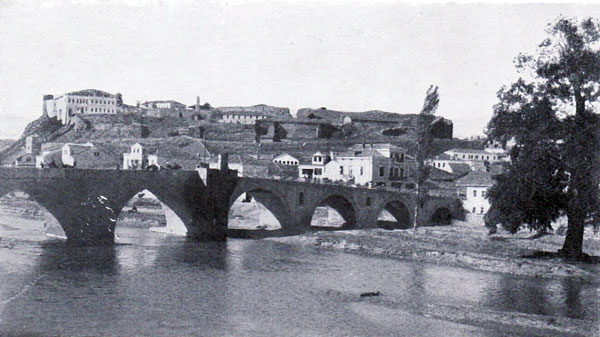

Bridge over the Vardar in Skopje

(Photo: Huge Grothe, 1913)

One morning, two days before my arrival in Skopje, the inhabitants caught sight of headless corpses of Albanian piled up under the main bridge over the Vardar, right in the centre of town. Some said they were local Albanians slain by the komitadjis. Others said the bodies had been carried down the river. At any rate, the headless victims had not died in battle…

Skopje is one vast military encampment. The inhabitants, the Muslims in particular, have gone into hiding. There are only soldiers to be seen on the streets. Mixed among the masses of soldiers are Serbian peasants who have come here from all over Serbia. On the pretext of meeting their sons and brothers, they swarmed over Kosovo Polje and.. plundered. I talked to three of these marauding peasants. They had walked from Šumadija in central Serbia to Kosovo Polje. The youngest of them, a little spunk, bragged that he had shot two Albanians at Kosovo Polje with an automatic weapon. ‘Actually there were four of them, but two got away.’ His companions, older and more mature farmers, confirmed what he said. ‘There’s one problem though,’ they complained, ‘we did not bring enough money with us. You can get a lot of oxen and horses here. If you pay a soldier two dinars (76 kopeks), he will go over to the closest Albanian village and bring you back a good horse. You can get a span of oxen, good ones at that, from the soldiers for 20 dinars.’ Masses of people from the Vranje region have forced their way into the Albanian villages and taken whatever they could find. The farm women even carry doors and windows from Albanian houses back on their shoulders.

Two soldiers approached me. They were cavalrymen from a unit that had disarmed the Albanians in the villages. One of the soldiers asked where he could sell a gold lira. I asked to see it because I had never seen any Turkish coins. The soldier looked around apprehensively and then took the lira out of his purse, but the way he did it made it obvious that he had more coins in the purse and did not want the others to know. And, as you know, a Turkish lira is worth 23 francs.

Three soldiers passed by. I heard their conversation.

‘I’ve killed loads of Albanians,’ one said, ‘but I haven’t found a single penny on anyone of them. But when I killed a bula (young Turkish peasant woman), I found ten gold liras on her.’

And they talk about such things here quite openly, calmly and equivocally. It has become something quite normal. The people don’t notice the huge inner changes they underwent in the first few days of the war. How people depend on circumstances! In an atmosphere of organised brutality, people become brutes themselves without even noticing it.

A column of soldiers is marching down the main street. One drunken and obviously mentally handicapped Turk curses them from behind. The soldiers stop, drag the Turk over to the nearest house and shoot him on the spot. Then they continue down the street, and the crowds go their way. The matter is solved.

At the hotel in the evening, I meet a corporal whom I know. His unit is situated near Ferizović [Ferizaj], the centre of the Albanians in Old Serbia. The corporal and his soldiers had just hauled a heavy siege cannon over the Kačanik Pass to Skopje, from where it was to be sent on to Odrin [Adrianople/Edirne].

‘And what are you now doing in Ferizović among the Albanians?’ I ask.

‘We are roasting chickens and slaughtering Albanians. But we’ve had enough of it,’ he added with a yawn and a gesture of weariness and indifference. ‘Yet there are some very rich people among them. Near Ferizović we came across a village, a wealthy village, with houses like fortresses. So we went into one of the houses. The owner was a wealthy old man, who had three sons. So there were four of them, and lots of women, too. We drove them all out of the house, stood the women up in a line and slaughtered the men folk before their eyes. Nothing happened. The women did not break into tears. It almost looked as if they were indifferent. They only asked to be able to go back into the house to get their personal belongings. We let them. When they came out, they brought each of us expensive gifts. Then we set the whole place on fire.’

‘But, how could you behave in such a bestial manner?’ I asked in shock.

Mosque of Mustapha Pasha in Skopje,

built in 1492 (Photo: Robert Elsie, 2007)

‘That’s just the way it is; you get used to it. There were moments I felt queasy when I had to kill some old man or an innocent young boy. But we are at war, and you know yourself, when your commander gives an order, you have to obey. A lot of things have taken place recently. When we were hauling the cannon to Skopje, we came across a wagon with four farmers lying in it, covered up to their waists. I could smell Iodoform. It was very suspicious. I stopped the wagon and asked who they were and where they were going. They kept silent and acted as if they did not understand Serbian. But there was a driver with them, a gypsy, who replied that the four of them were Albanians who had taken part in the Battle of Merdar, had been wounded in the legs and were returning home. It was all clear. “Get out,’ I ordered. They understood what was going to happen, and refused. What else could I do? I took my bayonet and finished all four of them off, in the wagon…’

I met another fellow. He was a waiter in Kragujevac, a young man with no particular talents, and no means a fighter. Just a waiter, like you find everywhere. He had been in the waiters’ union for a time and had even been secretary of the union for a while, but then he resigned… and now you could see what two or three weeks of war had done to him.

‘You people have turned into real bandits! You murder and steal from everyone!’ I cried, shrinking away from him in physical disgust.

The corporal was embarrassed. Events were obviously coming back to him and he was reflecting. Then, full of conviction, as if to justify himself, he said something that cast an even worse light on everything I had seen and heard.

‘No! We are regular armed forces protecting our borders and don’t kill anyone under the age of twelve. I don’t know anything about the komitadjis, it is probably different with them. But I can vouch for the army.’

The corporal did not want to vouch for the komitadjis. And they were certainly not protecting any borders. Most of them were good-for-nothings, bandits, depraved elements of the lumpenproletariat recruited from the dregs of society. They transformed murder, theft and violence into a savage sport. Their deeds spoke so obviously against them that even the military authorities were nervous about the bloody Bacchanals into which the chetnik fighting had degenerated, and took drastic measures. Without waiting for the end of the war, they disarmed the komitadjis and sent them back home.

I had no strength to endure the atmosphere any longer; I couldn’t breathe. My political interest and enormous moral curiosity to see what was going on was gone, vanished. All that remained was the wish to get away as fast as possible. And so I found myself once again in a cattle car. I stared out at the endless plain of Skopje. Such an expanse, and so beautiful, what a nice place it could be to live. But no. But, what am I telling you. You have had such nightmares yourself, but I had them ten times as strong since I have been here. Fifteen minutes after the train left the station, I saw a body lying two hundred paces from the railway tracks. It was wearing a fez. The body was lying with its face to the ground and with its arms stretched out. Fifty paces closer to the tracks were two Serbian militiamen belonging to a unit responsible for protecting the tracks. They were talking and laughing, one of them pointing to the corpse. It was obviously of their doing. I want only to get away!

Not far from Kumanovo, on a meadow beside the tracks, soldiers were digging huge ditches in the earth. I asked them what they were doing. They replied that the ditches were for rotten meat from the 15 to 20 train cars waiting on a side track. Apparently, the soldiers were not reporting to get their meat rations. Everything they needed, and more, they got directly out of Albanian houses: milk, cheese, honey. ‘In the last little while, I have eaten more honey in Albanian houses than in my whole life,’ boasted a soldier I knew. Every day, the soldiers slaughtered oxen, sheep, pigs and chickens, eating what they could and throwing the remainder away. ‘We don’t need any meat at all,’ said a supplies officer, ‘what we need is bread. We have written to Belgrade hundreds of times, telling them not to send us any more meat, but they don’t react.’

So, that is the situation seen from the ground. The flesh is rotting, both that of the oxen and of people. Villages have transformed themselves into columns of smoke. People not ‘under the age of twelve’ are exterminating one another. They have all turned into savages and lost their humanity. The moment you lift even the corner of the curtain on these military exploits, the war reveals itself more than anything as an abomination.”

[First published in: Kievskaya Mysl, Kiev, No. 355, 23 December 1912. Printed in Balkany i balkanskaya voyna, in Leo Trotsky, Sočinenia, vol. 6 (Moscow & Leningrad 1926), reprinted in German in Leo Trotzki, Die Balkankriege 1912-13 (Essen: Arbeiterpresse 1996), p. 297-303. Translated by Robert Elsie.]

TOP