1912

Ekrem bey Vlora:

Impressions from Vlora at the Time of Albanian

Independence

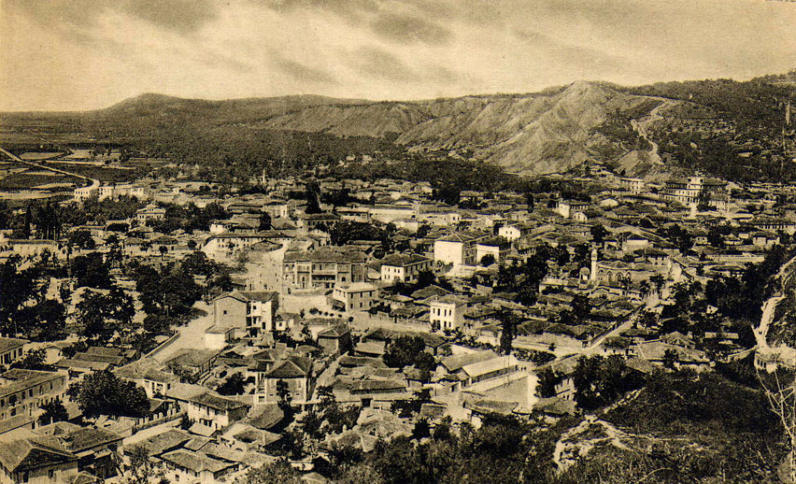

The Albanian nobleman and public figure, Ekrem bey Vlora (1885-1964), scion of the wealthy, landowning Vlora family, was in the town of Vlora around the time of the declaration of Albanian independence in the autumn of 1912. Here are some of his impressions, taken from his memoirs. When Ismail Qemal bey Vlora reached Vlora with his convoy of refugees on the evening of 27 November 1912 and took up residence in the selamlik of the Vlora family konak where he had been born almost seventy years earlier, a gathering took place where it was decided to declare Albanian independence the following day. Alas, the predictions and apprehensions of chaos that my father and I had, turned out to be true at this very first gathering. Aside from some notables who had been informed by Syreja bey Vlora in August, no one had been chosen from among the population of the district itself to take part in this ‘assembly of the will of the people.’ They were forced to choose representatives of the various regions of Vlora from among the newly arrived refugees, preferring men who had a certain position and a good number of followers in the countryside. For this reason, during the initial assembly that took place on 28 November, it was at the last minute that about forty men from the various districts of Albania were summoned to attend. Further delegates arrived from southern and eastern Albania on the following days. However, I am convinced to this very day that the men chosen for the assembly, and thus the assembly itself, were of no great importance. All of the refugees and all those Albanians who had remained behind in their towns and villages under the yoke of the enemy would have voted for what was decided upon in Vlora in that catastrophic situation. In stressing this particular aspect of the first national assembly, I wish to underline the provisional, ad hoc character of all the measures that were taken subsequently in Vlora. The region under the control of the government hardly made up 4,000 square kilometres but had a population of perhaps 250,000 (including the refugees). If we include the 30,000 to 40,000 Turkish soldiers who had also taken refuge there, it can easily be said that in the first months, the provisional government ruled over about 300,000 people – one of the largest ‘sanjaks’ in the former Ottoman Empire. Of course, the situation was much more difficult than in peace time. Hundreds of new problems arose for the people in this region following the collapse of the central authorities, problems that no one had foreseen and everyone expected would be solved by someone else because they had no capacity or interest in solving them themselves. Everyone proclaimed the traditional Albanian values of duty, patriotism, self-sacrifice, hospitality, peace and order, but at the same time they all showed that they had no understanding for issues of organisation which are essential to building a State. This has always been the weak point of the Albanians, and this is why the provisional government in Vlora failed. Someone might ask: “But who failed?” There is no one I can accuse or defend in particular. All I can say would be: “Everyone,” all those who took on responsibilities for the administration and organisation of the country, “everyone” without exception! It was only the people, the simple people, who did their duty. They paid their taxes down to the last penny (which they had not done earlier), kept peace and order and, where necessary, made great sacrifice. It reminded me greatly of what I had experienced in Skopje in July. On my return from Kuç, I immediately went to see the heads of the provisional government in the house of my cousin Xhemil. The house was a smaller copy of our haremlik and had two floors instead of three. I went through the connecting gate into the hall on the main floor where the staircase was. The entrance, the halls on both floors and the staircases were full of people – faces, figures and costumes I had never seen before in Vlora. Everyone was talking loudly and all were moving around throughout the house whenever they seemed to be bored where they were. There was a large hall on the upper floor with Biedermeier furniture, the door of which was wide open. People pushed back and forth to hear what was going on inside. I spent a couple of minutes there to say hello to some friends and then proceeded into the parlour. Ismail bey was sitting on a sofa, slumped over and with an expression on his face that was painful to look at. I had not seen him for three years, and he now looked old and exhausted. It was evident that he did not feel at home in this new and foreign environment. For years, he had served as a high-level Turkish official and dignitary, in positions where the difference between upper and lower were respected. Now he was in a vortex of social confusion and did not understand the world anymore. When I approached, he rose slightly from the sofa to greet me. I then kissed his hand in respect and sat down beside him. The crowd that filled the room had at least left him the sofa to sit on. He asked the usual polite questions: how I had been, where my father was, if I had suffered greatly from the bad weather in Kuç, etc. I then got up and wanted to leave. He held me back and asked in a low voice: “I would like to come and visit you. Are things as bad at your place as they are here?” I replied that I would be glad to pick him up whenever he wanted. “No,” he answered, “Xhemil told me about the connecting gate that is apparently still there. I can find my way.” In actual fact, things were no better at my place, though people kept their distance somewhat more because of my aloof, unapproachable character. One might ask who it was who caused all the commotion in a private house. Ismail bey had learned from his father and grandfather that the home of a sanjak bey was ipso facto a seat of government. This is why the selamlik of a bey is called zapana in Albanian (from Turkish-Arabic zapt-hane, the place in which order and discipline are preserved). Ismail bey was thus unwilling to work at a regional government office, so the supplicants, with or without reason, had to come to him in his private home. View of Vlora in Albania, looking northwards (photo: Mer Bali, pre-1918). In the following days I paid visits to the high officials of the new government that had taken office on 4 December 1912 with Ismail bey as president, and the Reverend Dom Nikolla Kaçorri, representative of the Catholic Bishop of Durrës, as vice-president. The members of the new government were good friends of mine and I have to admit that, under the circumstances at the time, no better choice could have been made. It would be unfair to reproach them for not being up to the demands of the times. The situation of any freedom-loving government would have been difficult after the collapse of Ottoman rule. Perhaps only a strong-handed dictatorship would have been more successful in keeping control. But where was the dictator? There was no room in the government of Ismail Qemal bey and Dom Nikola Kaçorri for feudal tyrants. Respectable individuals were now in power. The Council of Ministers met at the home of Ismail bey. I never found out where the ministers had their various ministries although I knew Vlora well, miserable hole that it was. The luckiest of them was the Minister of Posts and Telegraphs. He had a whole ministry to himself, i.e. the post and telegraph office in Vlora. The national assembly that had proclaimed Albania’s independence on 28 November 1912, dissolved on 7 December 1912, having appointed an eighteen-member council of elders (senate) to replace it. During my absence in Kuç, I had been elected as the deputy for Vlora and now as a senator. My friends among the ministers were Myfit bey Libohova and Abdi bey Toptani. These two men were very different, indeed opposing characters. Myfit bey dealt with the failings of the provisional government, the immaturity of the Albanian people and the hardship that had befallen it with a good deal of humour. Abdi bey, on the other hand, was at times depressed and forlorn, for example when the payment of salaries in the new Albanian State was delayed by a week or two. We often wondered where the Albanians had so quickly learned the term ‘monthly salary.’ There was no real way to solve the finance problem, i.e. to find enough money for the administration of government and for the huge number of refugees. In Turkish and Albanian terms, Vlora and Berat were rich provinces. However, revenues from the customs office dwindled to nothing because of the Greek blockade. It would have been no less than a miracle if Abdi bey had succeeded in keeping the provisional government afloat with the 6,000 to 7,000 Napoleons, or 120,000 to 140,000 gold francs, available to it. It should be noted that none of the beys, without exception, accepted a penny in salary or remuneration. Myfit bey, the minister of the interior, lived at my home for several weeks and then rented a pleasant house behind our garden wall where he lived while he was in Vlora (Gjirokastra and Libohova were occupied by the Greeks). His ministry functioned in a way that reminded me of the times of good King Dagobert of the Franks – paternal, somewhat chivalrous and somewhat despotic. In April 1913, when the blockade was over, an unknown newspaper reporter came over from Italy. He was ceremoniously greeted and welcomed by the authorities, like the first swallows that arrive in the spring. He was also given horses and assistants so that he could visit the whole region under government authority, and all at government expense. His reports appeared in the Italian newspapers a week later. They contained not only strong criticism of the provisional government that had been unable to overcome “all the failings of centuries of mismanagement,” but a libelous defamation of Albanians and praise of the Greeks and Serbs. To top things off, the newspaper correspondent made fun of the Albanian people and the provisional government for the very hospitality they had shown him when so many of them were starving. Myfit bey summoned the newspaper correspondent, showed him the articles and asked him in a friendly tone if, during his travels, he had not noticed the self-sacrifice of the Albanians, the peace and order in the country, and the good will that the Albanians had shown to try to improve the situation. The man was insolent and stupid. He stated that he was a free newspaper reporter from a “large country” and would not let the Albanians tell him what he was to publish. “Is that right?” answered Myfit bey. “Well, then I will give you an opportunity to report about something really authentic in Albania.” Four of his men seized the terrified fellow, stretched him out on his belly and a fifth guard gave the reporter a good thrashing, twenty whiplashes on the fattest part of his body. A week after my return to Vlora, I sent Murat bey Toptani and Hydai Efendi (the nephews of the abbot of our convent in Kanina) to Ismail bey to ask for the return of the flag I had lent them. They promised to return it in a few days as soon as Ms Marigo Posio (a fine democrat and patriot from Korça who knew how to make herself known) had finished sewing and embroidering the new flags. On 28 November the Albanians, in their typical oriental carelessness, forgot the main symbol of the day, the flag as a token of our sovereignty. Most of them did not even know what the flag looked like. No one had ever seen or used it, and no one in Vlora owned one. The great fathers of the nation looked at one another in perplexity. My friend Hydai Efendi then announced that I, Ekrem bey, had a well-framed Albanian flag on the wall of my bedroom. He asked if they were interested in using it, although I was absent at the time. Ismail bey agreed and thus the flag presented to me ceremoniously by Don Aladro Castriota in Paris was transferred from the konak to the hands of Ismail bey. Murat bey Toptani handed it over with the suggestion that it be raised while Ismail bey stood at the window. Thousands of people had gathered in the courtyard and gardens. They all applauded and shouted “Long live!!” although most of them had no idea what the ceremony was all about. Seeing me exhibit the same Albanian flag later on the occasion of the recognition of Albania as a free and independent State, some Albanians from Kosovo said: “You educated men did well to put up the flag of Bab Krali (father king – a reference to the Emperor Franz Josef of Austria-Hungary). At least that way the shifty Serbs and the lousy Montenegrins will leave us in peace and quiet.” When I asked them where they had seen the black eagle, they replied proudly, “Among the soldiers of Bab Krali in Novi Pazar.” There was a certain Haxhi Muhamet Efendi, an important and fanatic Muslim cleric from Vlora who was in my father’s party. He was infuriated and alleged that Ismail bey had chosen a ‘raven’ as the symbol of a free Albania. “Oh, if Syreja bey had founded Albania,” he moaned, “we would now have a fine verse from the Koran on our flag. But what else can you expect of Ismail bey who has spent his whole life in Frengji (the land of the Franks)!” When I told this story to Ismail bey, he laughed heartily, but threatened to reveal to the cleric that the flag was mine, not his. [Extract from: Ekrem bey Vlora, Lebenserinnerungen (Munich: R. Oldenbourg, 1973, vol. 2, p. 3-10. Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.]

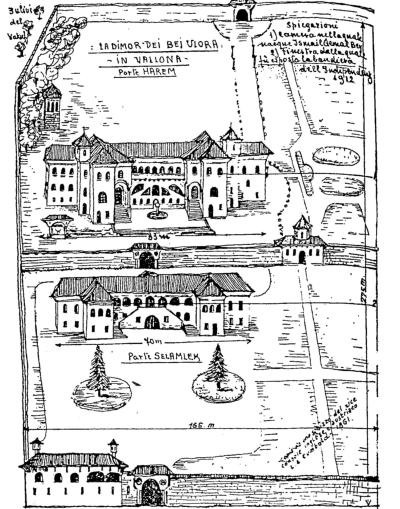

Sketch of the manor (konak) of the landowning

Vlora family in the town of Vlora, Albania.

Ismail Qemal bey Vlora (1844-1919).

Early Albanian flag from the collection of Ekrem bey Vlora,

now preserved at the Institute of Folk Culture in Tirana.

The grave of Ekrem bey Vlora (1885-1964) in Kanina

overlooking the Bay of Vlora in Albania

(photo: Robert Elsie, 20 May 2017).

| Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact |