| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

![]()

Delegates of the Congress of Trieste

(Photo: Marubbi).

1913

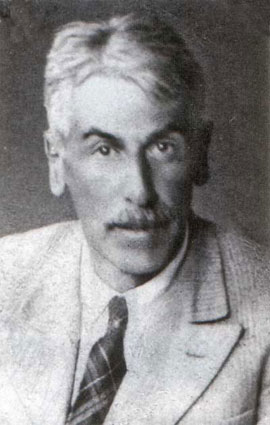

Baron Franz Nopcsa:

The Congress of TriesteFranz Baron Nopcsa (1877-1933), was born the son of Hungarian aristocrats at the family estate in Szacsal near Hatzeg in Transylvania. He was able to finish his schooling at the Maria-Theresianum in Vienna with the support of his uncle and godfather, Franz von Nopcsa, who was headmaster of the court of the Empress Elisabeth. Nopcsa developed quickly into a talented scholar. He travelled extensively in the Balkans and lived in Shkodra for some time in the early years of the twentieth century. He soon became one of the leading Albania specialists of his times and was even a candidate for the Albanian throne in 1913.

His fifty-four publications in the field of Albanian studies from 1907 to 1932 were concentrated primarily in the fields of prehistory, early Balkan history, ethnology, geography, modern history and Albanian customary law The list of Nopcsa’s publications includes over 186 works, primarily in the fields of palaeontology, geology, and Albanian studies. Suffering from depression, Baron Nopcsa committed suicide at his home in Vienna on 25 April 1933 and killed his longtime Albanian secretary and lover Bajazid Elmaz Doda (ca. 1888-1933). His memoirs “Reisen in den Balkan: die Lebenserinnerungen des Franz Baron Nopcsa” (Travels in the Balkans: The Memoirs of Baron Franz Nopcsa), Peja 2001, from which the following extract is taken, were published posthumously. This text deals with the Albanian Congress of Trieste in 1913 and with Nopcsa’s candidacy for the Albanian throne.

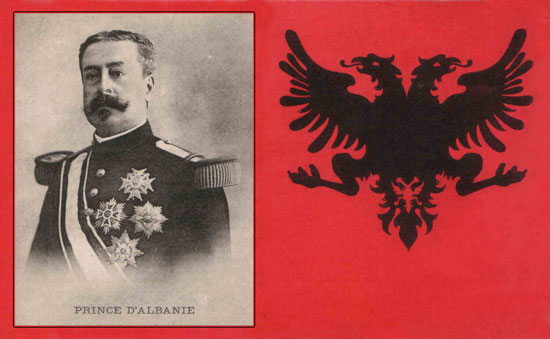

The Congress of Trieste, Alb. “Kongresi i Triestit,” was convened in early 1913 to show solidarity among Albanians from Albania and abroad for their country following the declaration of independence in Vlora on 28 November 1912. About 150 representatives from Albania, Romania, Bulgaria, Italy, Egypt, Turkey and the United States attended to discuss the affairs of the nation. The congress recognized the provisional government set up by Ismail Qemal bey Vlora and discussed the various candidates for the new vacant throne. Among the candidates being discussed at the time were Ferdinand François Bourbon Orléans-Montpensier of France, Albert Ghika of Romania, Count Urach of Württemberg, the Egyptian prince Ahmed Fuad, and the son of the Marchese Castriota from Naples. Austria-Hungary promoted the congress, in particular to ensure the selection of a prince of its choice.

Juan Aladro Castriota, a candidat for

the Albanian throne. Postcard 1913

From 27 February to 6 March (1913) I took part in the Albanian Congress of Trieste. This congress was a strange affair. The Albanian throne was vacant in the spring of 1913 and Albanian affairs were under the direction of Ismail Qemali who had first met with Berchtold in Budapest at the home of Excellency Hadik Janos and had then journeyed to Vlora, entrusted by him and with his support. There he formed the provisional government of the newly founded Albanian state. As a long-term friend of the Greeks and as their paid agent, he also promised to facilitate their occupation of Janina if he remained head of Albania. It is obvious that Ismail Qemali wished to remain at the head of the provisional government because such positions usually bring in a lot of money. Less obvious was the fact that Berchtold, after a tête-à-tête with Ismail Qemali, was convinced that he could outmanoeuvre the Albanian leader. And of course he failed. I was easily able to foresee that Ismail Qemali would betray Albania to Greece because Stead had told me much about Qemali’s relations with Greece in 1911 and because the writer Alexander Ular, author together with Enrico Insabato of the book ‘Der erlöschende Halbmond’ [The waning crescent], Frankfurt 1909, had revealed to me a number of details about Ismail’s conduct as Governor of Tripoli. When Berchtold asked me what I thought of Ismail Qemali two weeks after he had founded the provisional government, I said to him quite literally, “Ismail Qemali is an ass.” Ismail Qemali’s betrayal of Albania was confirmed to me completely by Eqrem Bey Vlora, who was himself the son of the Albanian ambassador in Vienna, Sureja Bey, and the nephew of Ismail Qemali. I do not know what the Greeks intended to do with Ismail Qemali once they had occupied Janina. Perhaps they wished to proceed according to the old saying, “The Moor has done his duty, the Moor may now depart.” At any rate, intensive propaganda campaigns were being waged in Europe on behalf of the various pretenders to the Albanian throne while the provisional government was being headed by Ismail Qemali, who was open to bribery, though only with large sums of money.

Albert Ghica, who had been a pretender to the Albanian throne himself, had managed to interest the Duke of Montpensier [Ferdinand François Bourbon Orléans-Montpensier] in the Albanian throne. He ceded his ‘rights,’ which were recognized by no one as a matter of fact, to the duke and began to campaign on his behalf in exchange for an appropriate remuneration. Montpensier easily won over the miserly Fazil Pasha Toptani and a number of other Albanians, and thus arose the plan to have Montpensier proclaimed King of Albania at the Congress of Trieste. Montpensier was at the same time to break through the Greek blockade and take possession of Vlora and of Ismail Qemali. Because our Monarchy, in view of Montpensier’s relatives, was expected to resist this choice, it was shown to be expedient for the Albanian Congress to be supported by Austria-Hungary. A decision was then taken to hold the congress in the Monarchy in order to lay a real diplomatic cuckoo’s egg. As a strawman for convoking the conference, skilled use was made of the kind, but dumbwitted Stefan Zurani, who suspected nothing. Curani was naive, ambitious and well viewed at the foreign ministry, and out of pure vanity claimed to the foreign ministry that he himself had had the idea of convoking the Albanian Congress in Trieste. Since the foreign ministry enjoyed the idea of Albanians in the Monarchy demonstrating on behalf of their country, the plan was accepted and supported by Vienna. Aside from the Albanians themselves, the Italo-Albanians also turned up at the congress, and with them came Marchese Castriota from Naples with all of his sons. Also present was Albert Ghika, Baron Dungern, who was a university professor and historian from Czernowitz, two Christian-Socialist Members of Parliament, Count Taaffe and Mr Panty from Vienna, as well as the Rome correspondent of the ‘Reichspost,’ Cavaliere Mayerhöfer, and myself. I brought with me Dr Leo Freundlich, a former Socialist Member of Parliament from Vienna who, at the very moment Albania became ‘in,’ had skilfully founded the periodical ‘Albanische Korrespondenz’ and was now on about ‘imperialist power politics.’ Hasan Arnauti was in Trieste, too, as my private detective. The press was represented by various newspapers. Also in Trieste was a certain Mr Jovo Weis from Belgrade who, it was said, wanted to sell rifles to the Albanians at a price of 90 crowns a piece, but who in reality was a Serbian agent.

Representing the Austrian Government was Makavetz, a calm, intelligent and energetic figure who never lost his composure. After welcoming ceremonies the first evening, Marchese Castriota was chosen as honorary president of the congress and Faik Bey Konitza was elected chairman. Hilë Mosi, Fazil Toptani and Dervish Hima were also elected to the chair. The nomination of Konitza was not to the liking of Ghika since, when the latter was on the point of bringing up the issue of candidates to the Albanian throne, his old rival Faik prevented him from doing so. In order to have an ace in his hand, Ghika, who like many a Romanian had a long career as an impostor behind him, had cunningly succeeded in getting control of Ismail Qemali’s retarded son. Before the congress started, he travelled to Nice, where the Qemali family resided in virtual poverty, and, as Qemali himself was unable to attend, invited the son Tahir to the Albanian Congress in Trieste at his own expense, or, to be more precise, at the expense of Montpensier. Since Tahir did not have a penny to his name and had to have everything, even his cigarettes, bought for him by Ghika and as such could not do anything without Ghika or his representative, he had virtually become Ghika’s prisoner. What Ghika intended to do with Tahir only became clear at a later date...

Since the many Italo-Albanians attending the congress were becoming over-bearing with their Italian-language speeches, I had myself introduced at the opening by Faik as an old friend of the Albanians. I had but a few minutes to think of my reply, mounted the podium and held a spontaneous speech in Albanian. With the exception of Kral and a few other Austro-Hungarian and Italian consuls, I don’t think many a central European would be in a position to repeat that feat.

All in all, there was nothing but hot air at the congress, aside from a dispute between the Vlachs and Albanians, during which the little nation of Vlachs, not even officially born yet, gave substantial proof of its fanaticism and Balkan megalomania, and from a further clash between the chairman Faik Bey Konitza and the rather crooked Nikolla Ivanaj, who endeavoured unsuccessfully to challenge the authority of the chairman simply in order to draw attention to himself. The day before the congress was to end, I therefore felt compelled to call Faik Bey Konitza aside and inform him that the congress had as yet done no work at all and that the least one could expect from a political congress was a resolution. Faik agreed and I dictated to him a resolution which the congress was to telegraph to all the Great Powers the next day. The matter was attended to within half an hour, and the next day, Faik presented the document to the congress as a resolution. After a debate on the position of the Vlachs at the congress and in a future Albania, which Faik overcame in favour of the Albanians by presenting the Vlachs more or less with an ultimatum, the resolution was accepted and, as such, my text was sent to the Great Powers as the congress resolution.

During the congress, Cavaliere Mayerhöfer learned from Tahir, the son of Ismail Qemali, that Montpensier was preparing a putsch. He informed me, but aside from this no one else found out, not even Freundlich and Dungern. The two of us informed Makavetz, who told the foreign ministry. All necessary countermeasures were prepared. Ghika’s plan to bring the throne question up at the congress had failed, but another coup was in the making since Montpensier disposed of a yacht ready for sail. We spent two days in Trieste waiting to find out what Vienna thought of Montpensier’s candidacy, in particular in view of his relationship with the Archduchess Maria Dorothea. The Albanians, among whom Faik Bey, began to ask us how they should react to the candidacy. I said to them on my own behalf, “In a hostile manner, for I do not believe that Montpensier is a candidate for Vienna.” In the end, the reply arrived, confirming my suspicions. We were now free to act against Montpensier. As it happened, the Viennese Members of Parliament were holding a banquet for the congress at the Palace Hotel. I interrupted a pause in the conversation by saying in an audible voice, “I hear that Montpensier wants to become King of Albania and that proclamations have already been printed! Does anyone of the gentlemen here happen to have one in his pocket? You know, gentlemen, I am a great collector of printed material on Albania.” Tremendous surprise and a stunned silence. Fan Noli forgot himself, drew a proclamation out of his pocket and gave it to me. Montpensier’s secret was divulged. That evening the proclamation was in the mail on its way to Berchtold. Our worries were less now, but not done away with entirely.

The next day there occurred a dramatic moment at the congress when rumours suddenly began to fly that a messenger from the Provisional Government of Albania had arrived in Trieste from Vlora. A few minutes later a tall, but stooped and awkward-looking old man, exhausted from his journey, was conducted into the hall, causing great commotion. It was the Albanian minister, Kristo Meksi. He had arrived straight from Vlora. There was frenetic applause, the atmosphere was electrified. Faik turned pale for he realized that the chair had now lost all influence over the congress. It was now the Provisional Government that was in the chair. He did not know what message Meksi had brought with him. If Meksi, as a result of some secret agreement as an emissary of the Provisional Government in Vlora, were to proclaim the Duke of Montpensier as King of Albania, he would certainly be elected. I sat down next to the representative of the Austrian Government, Makavetz, and said, “You know, if Kristo Meksi proposes Montpensier as a candidate, we are lost because he will be proclaimed unanimously.” Makavetz remained externally calm but every hair on his head was raised. He was prepared to let the scandal happen and to end the congress. Kristo Meksi began to speak. He conveyed to the Albanian Congress the best wishes of the Provisional Government and informed those present that the members of the Government were all well. Then, without even realizing what decision was in his hands, he left the podium to the frenetic applause of the auditorium. The storm had passed. We realized that Ismail Qemali had not yet been informed of Montpensier’s plan.

Now it was simply a matter of freeing Tahir from the clutches of Ghika. A coincidence facilitated our plan. Ghika did not wish to pay Tahir’s hotel bill and had turned to others to solve the problem for him. As such, an Albanian patriot soon made his appearance. I believe it was Mark Kakarriqi or Koci who approached me and explained that Tahir, the son of the president of the Albanian Government, was in financial difficulties. Knowing me to be a friend of the Albanians, the patriot asked me if I would be willing to assist by paying Tahir’s debts, adding that, if the matter became known to the public, it would put Albania in a bad light. Tahir needed 500-600 crowns and, I was told, was too embarrassed to approach me directly. I declared myself willing to assist immediately and promised to pay his expenditures that very afternoon. At noon I dined with Tahir and Mayerhöfer and succeeded in making it clear to Tahir that he was being used as a tool and was in fact a hostage in Ghika’s hands. His father in Vlora could be compelled to resign from the Provisional Government in favour of Montpensier in order to save his son’s life. Tahir was of course dumbfounded and told me everything he knew, admitting, however, that he had no money to free himself from Ghika. I promised to arrange everything. I paid Tahir’s hotel bill that afternoon and left enough money for his expenses until the next day. I later met the Albanian patriot who had demanded 500-600 crowns and told him that I had already paid Tahir’s debts, but that he had made a mistake, the debt being a mere 190 crowns and not 500-600. An Albanian patriot was thus deprived of a sum of 300-400 crowns! I also invited Tahir to supper that evening and, in order to prevent him from talking to Ghika, who was staying at the same hotel, I got him drunk. At midnight I returned him reeling to his hotel where we met Ghika in the lobby. He understood what was going on and realized that he had lost out as far as Tahir was concerned. At my insistence, Tahir told him that he was leaving for Vienna, where he would be staying with me. All further contact between Ghika and Tahir was thus rendered impossible. The next morning I had Tahir’s luggage picked up and he set off for Vienna, this time as my prisoner, and once again without a penny to his name. I put him up at a hotel and subsequently bought him a train ticket to Nice, gave him some travelling money and sent him back to his mother. The Austrian Foreign Ministry also sent Mrs Ismail Qemali a larger sum of money to help her with her financial difficulties, in order that such a problem not occur again. In order to describe the level of Tahir’s intelligence, it is sufficient to note that he had been a Turkish naval cadet under Abdul Hamid. This tells it all. This was thus the extent of my involvement at the Albanian Congress of Trieste....

From Trieste I returned to Vienna, where I urged Berchtold to ensure that the recently created Albanian throne be occupied as quickly as possible because I foresaw the negative consequences of leaving it vacant for too long. He complained that he was unable to find a suitable candidate for the throne. There were in fact a good number of candidates. Foremost among them was Count Urach of Württemberg. An Egyptian prince, Ahmed Fuad, and the son of the Marchese Castriota of Naples had also made their candidacies known.

Baron Franz Nopcsa,

ca. 1928.

At this moment I resolved to take a step which could easily have made me a laughing stock and have put all my activities on behalf of Albania in a bad light. Nonetheless, I decided to go through with it. I informed Excellency Conrad verbally that I would be willing to join the list of candidates for the throne if the Foreign Ministry would support me and told him that, to have myself proclaimed King of Albania, I would simply need the one-time payment of a larger sum of money in order to buy the support of the so-called Albanian patriots which, as I learned from the Montpensier putsch, was no problem at all. Once a reigning European monarch, I would have no difficulty coming up with the further funds needed by marrying a wealthy American heiress aspiring to royalty, a step which under other circumstances I would have been loath to take. I was sure of the support of the inhabitants of the northern part of the country in view of the stance I had taken in the years 1910 and 1911 and Vienna could expect to overcome any difficulties caused by Ismail Qemali who was being supported by Berchtold...

My candidacy may have been ridiculed in competent circles. Be that as it may, I grew disgusted a few weeks later and withdrew from all further activities concerning Albania. Some of those in the know said that I only did so because my highfalutin plans had not come about. I for my part gave as my reason [for withdrawing my candidacy] that the Albania created by the Conference of London was a stillbirth. I did not even attempt to contradict the slanderous allegations which my opponents revelled in, because I knew that events to come would prove to be my best defence. The collapse of the Albanian State in 1914 showed that I was right to get off the sinking ship in time in 1913. My only ‘mistake’ was to have recognized what was to come long before my opponents did. Prince Wied ascended the Albanian throne while the Conference of London was still underway...

Soon after the Albanian Congress I resigned from the Albanian committee because of the borders set forth by London, and withdrew from all further political activity...

[Extract from: Reisen in den Balkan: Die Lebenserinnerungen des Franz Baron Nopcsa. Eingeleitet, herausgegeben und mit Anhang versehen von Robert Elsie, Peja: Dukagjini 2001, p. 228-296, 299-301. Translated from the Albanian by Robert Elsie.]

TOP