1914

page 1 | page 2

E. J. Dillon:

The Albanian Tangle

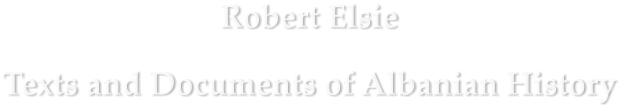

But the group of Mohammedans who thought and behaved thus was small and their opposition negligible. What subsequently made it appear formidable was the admixture of the Young Turkish element, which came into the country for the express purpose of disaffecting them towards the Prince, and played on the religious chord as the most likely one to evoke the requisite response. This propaganda, which took effect only on a few hodjas, may have misled the foreign officials at Durazzo, who at once talked of wild religious fanaticism, seriously apprehended a religious war, and unwittingly caused a panic in the capital. Religious fanaticism is practically unknown in Albania. There is too little real religion available for the purpose. It is lost labour to fan embers if there is no fuel for a fire. Catholicism and Islam became largely diluted with Albanian customs before being assimilated by this most conservative people in Europe. Each of the three faiths, Catholicism, Orthodoxy, and Islam had to stoop before it could conquer. None of them succeeded in doing away with the vendetta which is still answerable for three-fourths of the deaths of the Catholic mountaineers. A large percentage of the Mohammedans belong to a sect which the Turks abhor as semi-Christian. The adepts of this denomination, some of whose members I have myself questioned, leave the faces of their women uncovered, eat port, drink wine, reject the dogmas of creation and a future life, and the initiated among them hold a body of doctrine which may be roughly characterised as pantheistic materialism. They are the religious offshoot of the Janissaries, and their annals, still hardly known, are calculated to shed an interesting light on some of the salient events of Turkish history. Among other doctrines of the Bek Tashis, that of the equal value of all religions occupies a prominent place. It is worth noting parenthetically that Essad Pasha’s family, the Toptanis, has always been at daggers drawn with the Bek Tashis, of whom not a trace is to be found in those towns or districts like Shiak, Tirana, Kavaya, where his power was preponderant. The Bek Tashis have ever been the enemies of the Beys and Pashas. The Catholics of the northern mountains are of all Albanian Christians the most submissive to their clergy, to whom they pay dues in kind. But they are still more devoted to their chiefs, and when Prenk Bib Doda’s father quarrelled with the Bishops, he allowed his men to plunder and maltreat them, which they did with a will until the Church dignitaries knuckled down and asked for mercy. Among the Catholic troops faithful to the King are many Moslems, while a considerable percentage of Catholics is to be found among the Mohammedan insurgents of the centre, who were supposed to be ready to put the Christians of Durazzo to the sword. In view of these things, there would seem to be little doubt that many of those who are at the head of affairs in the capital of Albania have yet to learn the history and the psychology of the people whose destinies they are vainly endeavouring to shape. If, then, we eliminate religion as one of the decisive factors of the internal Albanian problem, we find as residue two elements which lie at its deepest roots: on the one hand, the feudal pyramid with the faithful clans at its base and the chieftains invested with absolute authority, including sometimes power of life and death, as its apex; and on the other hand, a strong natural current set against the power of the Beys and Pashas, and a longing to dispossess them of the land, both tendencies fomented by the doctrines and the practices of the Mohammedan Bek Tashis, and the Christian nationalist of the extreme wing. Such in general outline is the rude, benighted people whom Europe’s fiat is to turn into a united nation with a central government and a royal head. Now, it seems clear that one condition of success is that the continuity of this primitive tribal system shall not be broken suddenly; but it is equally clear that it should be swayed, directed, gradually modified and utilised at every stage of the process as an efficacious instrument of good government. (3) But a vast transformation such as this presupposes the supreme control of one strong and free man. Only a leader gifted with clear, direct vision, who puts his heart in his work, is alive to its difficulties, is capable of wide surveys, quick resolve, and tenacity of purpose – a man who is not afraid even of making a mistake – is needed to lead the people out of their camp of mediaeval ideas, barbarous customs, and antiquated traditions into the open air and fierce light of twentieth-century civilisation. The Albanians respect power and yield themselves readily to the fascination of personal strength and prowess. A King who moved among them, made their interests his, entered into their joys and sorrow, settled their disputes and showed that he was one of themselves, would win their sympathies, command their respect, and gradually move into the position now occupied by their hereditary chieftains. And the achievement of this feat might have been accelerated by associating real power, power like that of Prenk Bib Doda and Essad Pasha, with posts of responsibility in the Government. In this way a salutary principle of fermentation would have been introduced into this Olla Podrida of contrary currents and conflicting strivings. That the present ruler has not fulfilled those conditions is a fact; that he is incapable of fulfilling them is hardly more than a surmise. He can plead with truth that he is not a free agent. Prince Wilhelm Friedrich Heinrich zu Wied was raised to the throne of Albania on grounds of a negative rather than a positive order, which had little in common with the considerations that would have weighed with an elector whose principal aim was to adjust means to ends. Physically he is the ideal man for the Albanians – tall, well-built, of commanding presence and dignified gait. His other personal qualities are calculated to command respect or ensure affection. His manners are pleasing, his temper bright and cheerful. He is whole-hearted, generous, and chivalrous, ready to set public business above personal interests and to make heavy sacrifices to duty. Those are all admirable traits in an officer or a civil servant in a well-ordered State. But they are insufficient for a man whose life-task is to dissolve the entire framework of a feudal, disunited people; to put an end to the meaningless war of all against all, which has been the blight of the country for centuries; to make new channels for the energies thus diverted, and to fuse the various groups and units into a harmonious, properly organised State. Besides, it is doubtful whether he possesses independent initiative and adequate will-power. Albania’s new ruler, his critics complain, lives in his palace at Durazzo as Dejoces, the Mede, lived in his fantastic stronghold at Ecbatana, a being apart, almost of a different species from that of his subjects. His residence is an oasis in the desert. His surroundings – the people whom he had taken with him and those whom Europe had thrust upon him – are aliens who can seldom tell him what to do and can hardly ever show him how to do it. The whole atmosphere is foreign. And each of these outsiders is jealous of the other and eager to win ascendancy over the inexperienced Prince. Their powers, vaguely outlined, overlap; their ambitions have been stretched beyond their legitimate scope, and the upshot is confusion. Thus there was an International Commission of Control composed of men actuated by the very best intentions, but unable efficaciously to protect the King against his enemies and unwilling to supply the funds needed for the organisation of a band of native troops to protect him. Then there were the Dutch officers whom Europe despatched to organise a corps of gendarmes, and whose extreme zeal, scrupulous attention to minute detail, and impulsive action have been an unending cause of troubles and complications, national and international, ever since. For it was their amazing treatment of Essad Pasha and their unprovoked attack against the petitioners of Shiak and Tirana, who were misnamed insurgents and, at present, perhaps, merit this appellation, that brought government to a standstill and produced the panic in the capital which culminated in the flight of the Royal Family. It was the zealous Dutch officers also who, sacrificing to what they deemed the highest interests of the State – the capitulations on the one hand and their duty as subordinates which obliged them to consult the Ministry on the other hand, entered the house of an Italian subject, treated him and his acquaintance ungently, seized their papers, placed them under arrest, and then refused to accept the officer’s parole and the Italian Minister’s guarantee that they would appear before a court of inquiry when called upon. They then referred the matter to the Sovereign, whose orders they invoked as their warrant, and thus involved him in an international quarrel without the solace of a good cause. The ruins of the ‘Konak’ or royal palace in Durrës (Durazzo), Albania, in 1914. From the German satirical magazine ULK, Berlin. The Italian and Austrian Ministers are ex officio counsellors of the King, and it is commonly supposed, I know not with how much reason, that the advice of the one is often contrary to that of the other. In the Palace there were two professional political mentors, one an Italian officer named Castoldi, and the other an Austrian named Buchberger. In addition to the abundance of political wisdom supplied by all these bodies and individuals, there was the Cabinet and the Opposition. The former, under the leadership of Turkhan Pasha, an experienced diplomatist and gentleman of the good old school, advocated a policy of conciliation and prudent opportunism; while the latter consisted of the Nationalists, the extreme wing of which was composed of sincere but unripe patriots, impatient to see the great transformation realised, mouthing empty watchwords, descanting on the principles of high politics, and waiting for the moment when the reins of power shall fall to themselves. All these professional and amateur advisers, none of whom the Prince could afford to ignore, were honourable men who would fain regenerate the country as it should, in their opinion, be regenerated. They all cry “Forwards!” But as each of them has a different direction in mind, the Sovereign, uncertain which to take, is distraught and paralysed. All decent semblance of unity is gone. The various authorities, national and international, are engaged in the game of baulking each other, in which they have all been beaten except the Dutch officers, who have had their own way, to the disgust of the others and the detriment of the country. The resources of Albania, economic and other, are being drained to no purpose, and the taproot of the national life seems blighted. It was a Dutch officer, Colonel Thomson, an honest, hard-working, and loyal man, who first negotiated with the leaders of the Epirote insurgents. He had a direct authorisation (4) from Prince Wilhelm, and only from him, but as soon as he had effected a settlement of their claims, he was disavowed by the Cabinet, which then empowered the Commission of Control to come to terms. The Commission of Control went to Corfu and made concessions to the rebels, which the Cabinet accepted only with large reserves. These reserves, formulated emphatically in a document signed by all the Ministers, were omitted by somebody in the copy which was delivered to the Greeks! Then the Dutch officers refused to obey orders issued by Essad Pasha in his capacity as Minister of the Interior and titulary War Minister. Essad appealed to the King, whom he suspected of leanings towards the Dutch, and spoke with uncourtly frankness to his Majesty. The Cabinet upheld Essad, and between the latter and the Dutch officers, and in particular Major Slujs, there has been no love lost ever since. Essad had been a force in the country before the Prince’s arrival. He was then the spokesman of the orthodox Moslem population, which clamoured for a Moslem sovereign. But, resigning himself to the will of Europe, he journeyed to Neuwied with a deputation, which invited the Prince to rule over Albania. Although this act of patriotic renunciation had cost him his prestige and power among the Mohammedans, he still retained great influence, which he knew how to make the most of. His agents were men devoted to him, âmes damnées, who thought no sacrifice too great for their patron. Now, all that Essad Pasha strove for, although a man of vast ambition, was that he should have the shadow as he had the substance, and that his real power should be associated with corresponding rank in the Cabinet or the country, canalised and used for the behoof of the nation and its Sovereign. He wanted to play a prominent, if not the leading, part. Such, at least, that and nothing more, is my personal impression gathered from various talks I have had with him during the time that he and I lived together. It is, of course, only an impression; and this moderate wish was not grudged to him by Turkhan Pasha, who understood the psychology of the man and perceived how advantageous a bargain the new State and its ruler were making. The Prince, too, who is generous and unsuspecting, appears to have trusted his General, or to have dissembled any mistrust which may have been implanted in his mind by stories of Essad’s underhand dealings with Mohammedans, secret intelligence with Greeks, Montenegrins, Serbs, Young Turks, and Italians, which were current among his adversaries, and may have been believed by the over- zealous Dutchmen, whose discretion never equally their zeal. The children of Prince Wied, Marie Eleonor (1909-1956) and Carol Victor (1913-1973), with their governess and Albanian kawasses after their return to Germany. Schloss Waldenburg in Saxony around the autumn of 1915 (photo: Fürstlich Wiedisches Archiv, Neuwied, No. 8480). It was no secret in Durazzo, Scutari, Vallona, or Shiak that Essad was being closely watched by the Dutch and their police, some of whom listened too readily to the idle tales spread by interested and venal mischief-makers. To the Pasha it was galling. At last they claimed to have adequate proofs which satisfied them of the treason of their powerful enemy. But this evidence, if it exists, has never been adduced, nor was the shadowed man apprised of the cloud that hung over him. Essad Pasha is perhaps the shrewdest man in Albania, and one of the most supple and resourceful. His change of attitude on the question of a Moslem ruler offers an illustration of his opportunism and adaptability. That such a man, after such a sacrifice, should get entangled in a set of conflicting and hopeless movements against the State in which he was playing the first part after the Sovereign, is almost inconceivable. He realised that the Powers would never accept him as Sovereign. He was aware that they would never invite nor recognise a Mohammedan ruler. In a word, for an insurrectionary outbreak there was no goal. And he himself had nothing to gain and everything to lose by dabbling in plots and conspiracies. He is the owner of immense estates, the revenue from which will increase fifty-fold when order is permanently established and normal national life begins. Fidelity to the King was therefore his trump card, and he seems to have played it. The worst that one can lay to his charge – so far as I who know him, but not his accusers, can discern – was a desire to make himself necessary to the Prince, a wish to play the part of a Grand Seigneur, which he did to perfection, and a natural striving to increase his power and prestige. His great Catholic rival in the north, Prenk Bib Doda, behaved in a very different way. He, too, exercises unquestioned sway over his followers, who are far more numerous, and are kept in more strict subjection than Essad’s. But Doda accepted no Ministerial post, and declined to reside within the Royal sphere of attraction. He would gladly lend the Monarch some thousands of his tribesmen, as Ras Michael might have lent a military contingent to Menelik, but would not become a State organ. Essad Pasha declared for the new order of things before it was established. Bib Doda holds on to the old, and watches with curiosity the prophesied evolution from his conning-tower outside. One could not expect brave and loyal Dutch officers, whose business is the training of gendarmes, to analyse thus closely the psychology of Albania’s two great chiefs. They mistrusted Essad, and, scenting treason, ran him to earth. Turkhan Pasha, the Granz Vizier and wise moderator, had just gone to Rome and Buda-Pest, leaving Essad in charge, who was therefore War Minister, Home Secretary, and Grand Vizier all in one. In Shiak, Tirana, and Kavaya the malcontents who had refused him recruits for the South put their heads together and resolved to lodge a protest with the King against the Cabinet and against the puissant War Minister, whose power they resented and whose land they coveted. Other elements there also were among them, but neither the names of the primary instigators nor their aims have been ascertained with certitude. These remonstrants, armed as are all Albanians, were holding a meeting at Shiak one morning, when the King and Queen chanced to ride out in that direction. Shiak is a village about an hour’s walk from Durazzo. The King noticed with surprise the unwonted aspect of the place, the coming and going of the people, and their look of excitement, and soon afterwards he found the road barred by a dense throng. Divining the character of the manifestation, he turned his horse’s head and galloped back to the capital, disconcerted and out of sorts. And in truth this was an unpleasant surprise, which should have been spared him. He ought to have been made aware of the ferment among the population and advised not to approach the place at all, or only with a firm purpose to take the bull by the horns and talk plainly with his subjects. Some of his official advisers now hold that if he had continued his ride he would have been acclaimed by the crowd, whose sullen murmurs would have turned to enthusiasm. This forecast is probably correct. Albanians love a strong man and adore a venturesome one. But neither lack of strength nor lack of enterprise was responsible for his conduct. It was lack of knowledge. He was not prepared for the sight that met his eyes, and the stories of underground plottings and infamous treason, which he had listened to perhaps incredulously before, may now have floated through his mind with a deeper tinge of probability. Moreover, whatever proof of intrepidity he may have been ready to give he felt bound to postpone until he was alone. On this day and the next I was absent in Kalmetti, the guest of Prenk Bib Doda, so that what then happened I now describe not from personal observation, but from the sifted narrative of others. When I vacated my apartments in Essad Pasha’s house, he resolved to fit them up for his young Circassian wife, who took possession of them in the afternoon of the eventful day. Unimportant in itself, this circumstance seems to rebut the allegation of those who allege that he had organised a rising for that night or the next. Until conclusive evidence of this amazing charge is produced and winnowed, I, who knew the Pasha, cannot entertain the notion that he was at once stupid, treacherous, and suicidal, as he must have been if this count in the whispered indictment against him were true. Nor is this presumption in his favour weakened by significant allusions to certain supposed antecedents of his which the laxest moralist of the West could neither overlook nor condone. Those alleged misdeeds, if brought home to him, would merely mark him as a man of his race, country, and time. Saturated with peculiar notions and feelings, and equipped with an amoral sense common to the whole nation, which Western nations regard with abhorrence, the ethical quality of his conduct can be fairly gauged by no standard but that of his own countrymen. And their moral code often enjoins manslaughter, but always condemns treachery. The King, on his return from Shiak, sent for Essad and called for an explanation of his silence if he knew what was going on, or of his remissness if he was unaware of it. What answer was returned to this pertinent query I have had no means of learning, but I understand that the Pasha finally tendered his resignation, which was refused, and then pressed it many times on the King. On the same day, Essad and his rival, Major Slujs, whose relations were those of bitter enemies, met, clashed, and agreed that Durazzo could no longer hold them both. The Dutch officer is said to have roundly accused Essad – who was at that time his chief, as War Minister, Home Secretary and acting Grand Vizier – of treachery to the Prince and treason to the State. Forthwith the Pasha sought out the King, informed him of the altercation, and requested him to choose between himself and the Dutchman. The Prince, it is stated, intimated his resolve to maintain Essad at his post and to appoint Major Slujs to another part of Albania. The Major, it is said, refused to go. A few hours later, however, the King reconsidered his decision and declared for the Dutch officer. But the Pasha was not dismissed. On the contrary, the Sovereign treated him as Minister as late as 8 p.m. that night. Of this victory gained, it is alleged, by means of grave allegations against the Pasha, Essad’s rival made the utmost. A coup de main was carefully elaborated, of which the effect, and seemingly also the object, was not merely to remove, but to humiliate and enrage the one man of power and influence in the service of the King. It was also expected that he would be executed summarily as a traitor. Essad’s house was surrounded by armed men. Mountain guns were posted on the heights above it, and orders were issued to the gunners to open fire as soon as the concerted signal was given. In the dead of the night a messenger was sent by Major Slujs to the residence of the puissant Minister to notify him that the forces of the King were posted below, cannons pointed at the building, and gunners ready to fire, and that he had no choice but to obey his Sovereign’s orders, which were that all the armed men then on the premises should lay down their weapons. The delegate, finding the gate open, entered and knocked at the door of the bedroom. Essad, in his nightdress, opened it and, with sleepy eyes and astonished look, asked what he wanted. His stupefaction at the answer was intense and unfeigned, but it passed quickly; he complied with the demand and gave the order. His men laid down their arms, and it turned out that, instead of a hundred adherents, he had hardly more than a dozen. Throwing open the window, he leant out to catch a glimpse of what was going on below, and then called out, “Who is in command of the men?” The answer was, “Major Slujs.” “In that man I have no confidence,” explained the Pasha. Thereupon his men snatched up their weapons. Soon afterwards a shot was fired, which each side now attributes to the other, but probably came from Essad’s house. On this, the signal was given by the Dutch and the gun launched forth its projectiles. Essad’s wife fainted. One of his dependants was killed. Part of the roof of his house was blown away. The boom of the cannon and the crack of rifles broke the slumbers of peaceful citizens who rushed out of their homes affrighted. At this conjuncture an Italian artillery officer of the reserve – Captain Moltedo – a man of reckless bravery – appeared on the scene, and put an end to what bade fair to become a massacre. Moltedo had only arrived in Durazzo that day to enter upon his duties as commander of the Albanian artillery, to which he had been appointed by the Cabinet. Hearing the boom of the cannon, he left his house and rushed off to the War Minister to inquire what was wrong. Realising what was being done, he advised the Pasha to deliver up the weapons to him. The Minister complied unhesitatingly, whereupon the Dutch were notified and the firing ceased. Essad and all the other inmates of the house were arrested. As yet the Minister had been taxed with no definite crime. He now asked with what offence he was charged and who his accusers were. But to these fair questions there were no answers. “If I am innocent,” he exclaimed, “why have I, who am acting Grand Vizier, War Minister, and Home Secretary been treated like a desperate criminal? And if I am guilty in the eyes of my Sovereign, why am I not given an opportunity to rebut the charges against me?” To this query there was no answer, not even a reply. Some were for trying and punishing him summarily, others for deporting him. Finally, the latter course was decided on and Essad was taken about 8 a.m. to an Austrian warship anchored in front of Durazzo. Orders had been given that he was to be conducted to the landing place by a route behind that palace. That route, it is said, was lined with personal enemies of his, impatient to murder him. But Essad insisted on walking in front of the palace, and as he passed he saluted his Sovereign, who returned the greeting. From the Austrian he was soon transferred to an Italian warship, and subsequently conveyed to Italy. I returned to Durazzo on the following day, and found his colleagues dismayed, humiliated, enraged. The conspiracy against him had been hatched so secretly that they had had no inkling of it until the plan was carried out. And they were still ignorant alike of the authors and their motives, nor has the mystery as yet been cleared up. Their questions were met with oracular answers or more significant silence. Their telegrams were suppressed. The Dutch took possession of the Telegraph Office. Nobody knew what surprise was still in store. It was whispered that other Ministers who were friends of Essad were also proscribed. The young Dragoman of the Ministry who had been attached by Essad to my person – M. Stavro – was seized, roughly handled, and thrown into the filthiest hole of the filthiest Turkish prison. He besought his captors to allow the place to be cleansed of some of the ordure that covered the floor. His request was rejected with jibes. Next day he was set free, and the Dutch Major, with whom he had often transacted business for the Government, apologised to him and hoped he would forgive and forget. On the following day the same Major had him seized in the street and commanded him to give up Essad’s cipher. He answered that it had never been in his possession, that it was always kept by the Secretary. He was told he must go back to prison until he gave it up, and as he knew nothing about it, he was once more thrown into the loathsome cesspool. There he found the Secretary, who informed him that the cipher had already been given up to the Dutch and sealed by them. Soon afterwards he was released and solaced with fresh apologies. Now at last he was free, they told him. A day or two later, however, he was once more seized and entombed in the pestilent black hole of the Turkish prison, where he was kept for eleven days without trial or accusation – by order of the Dutch officers. A short autobiography of Essad, composed by himself for me, was among the papers seized. And neither the Cabinet nor I have been able to obtain possession of it ever since. Thus bereft of power and saddled with responsibility, the Ministers had no choice but to tender their resignation, which they did unanimously. The King demanded time for reflection and requested them meanwhile to carry on the current business of their respective departments. But the current business continued to be done by the Dutch and others, without even the knowledge of the Cabinet. M. Nogga, the Finance Minister, who throughout these days of utter anarchy preserved a cool head and gave sound advice to his colleagues and the King, pressed upon the latter the necessity of instituting a court of inquiry which should investigate the charges against Essad, and ascertain the origin and justification of the high-handed way in which he was treated. But no court of inquiry was appointed, no justification attempted, no statement made. Privately it was admitted that there was no evidence worthy of the name against the fallen Minister! Seeing itself thus reduced to become a screen for doings of a lawless character and disastrous tendency, the Cabinet, having waited some days longer, repaired in a body to the palace and handed in a written request to be formally relieved of functions which were being actually discharged by irresponsible persons. The King returning the same answer as before, the Ministers announced their inability to cover any longer with their names the fitful freaks of unknown individuals. That was Friday night, May 22nd. A few days before this the King had sent for and received 120 Catholic Malissores from the North to guard his palace and person. The Italian Minister doubted the wisdom of this measure, and said so. The Dutch officers, without consulting the Cabinet or the Commission of Control, despatched these men in the middle of the night to the camp of the malcontents, with orders to occupy Shiak and Tirana. The Malissores demurred at first, and then obeyed unwillingly, on the grounds that they were too few for a military expedition, and had come to Durazzo in their rich embroidered costumes, which made becoming uniforms for palace guards, but were unfitted for soldiers in the field. But the Dutch would take no excuse, and led the warriors to Shiak, where they were not molested. They were accompanied by a number of volunteers, including some foreigners with a taste for adventure. It was then 5 a.m., Saturday, May 23rd. Seeing that the attitude of the villagers of Shiak was not aggressive, the order was given to continue the march to Tirana. It was disobeyed by the Malissores, who refused to advance further. When the other members of the expedition had climbed the hill above Shiak, then, and only then, did the bullets begin to whistle past them. Their gun was taken, their own friends in Durazzo misdirecting their artillery fire, killed and wounded several of them, the villagers took about 130 prisoners, and the remainder returned to Durazzo, leaving their gun behind. The amazing tactics which had led to these deplorable results exasperated the Ministers, bewildered the Commissioners of Control, sent the foreign diplomatists flying to the palace, and engendered a feeling of insecurity in the capital. People argued that if the safety of the city depended upon officers with so little judgment and upon men with so little discipline, it was obviously at the mercy of any band of resolute rebels who cared to take it. After this the capital was indeed at the mercy of the rebels, who, if they entertained the designs attributed to them, might now have executed them without resistance. And as no doubt was entertained by the King’s trusted advisers that the capture of Durazzo was their main object, a panic ensued of the kind that seizes upon Christians who are about to fall into the hands of ruthless Chinese rebels or infuriated Bashi Bazouks. Helter-skelter, foreigners of distinction, men, women, and children, rushed to the landing-place and fled to the warships. The foreign Ministers, convinced that a massacre was at hand, urged on their lagging countrymen. In hot haste trunks and boxes were carried from the palace and the houses. Groups of men and women, scared to death, ran hither and thither, not knowing what they said or did. Extreme nationalists, expecting no mercy from the rebels, asked for asylum on board Italian war-vessels. The scenes of that memorable day supply an instructive object-lesson for the study of the psychology of the crowd. Meanwhile the reports made to the King were alarming. He was assured that the insurgents were already within half an hour of the city. And the statement was quite true, but it might have been uttered with equal truth the day before, or even earlier. For they were not marching, but only remaining in positions which they had held for days. Subsequently, indeed, they asseverated that their intention had been to depute some spokesmen to the King with a request that their grievances should be considered and redressed, and they complained that the King’s officers had gone out to them with rifles and guns and made war on them without warning or ultimatum. The Prince was also informed that the “advancing army” consisted of thousands of well-organized troops, fanaticised to frenzy by unknown agitators, and that at any moment they might enter the city and put the inhabitants to the sword. The marines, it was added, would have to be withdrawn and the city left to its fate. Hence it behoved the Royal Family to accept the hospitality of the warships betimes. This advice must have been repugnant to Prince Wilhelm, who, whatever else may be said of him, is an officer who knows no fear and sets duty above life. But what was duty? If your guide in a pitch- dark cave tells you to jump, and adds that the height is five feet, what can you do but carry out his behest, even though your eyes seem to assure you that there is no break in the level ground? True, there were other advisers who advocated a different course. The Finance Minister, Nogga, adjured the King to remain, declared that the insurgents harboured no blood-thirsty designs; that their number hardly amounted to more than three hundred men; that he would answer for it, that they would acclaim the King if he went out to them, and that in no case was there any ground for alarm. In the interests of the nation and the dynasty, therefore, he implored the King not to quit the city. A member of the Commission of Control urged the same arguments and proffered the same advice. The young monarch was bewildered. Alone he would have stayed where he was, but the Queen was resolved to remain with him. Finally, in order to induce her to quit the palace, he yielded to the insistence of the more influential counsellors, and decided to withdraw to one of the Italian warships. This was the most unlucky course he could have chosen. But a little forethought would have sufficed to counteract its most mischievous effects, and to mitigate the remainder. The King might, for instance, have announced his intention to escort his consort to the Italian warship and to return an hour or two later. He would then have an opportunity of seeing for himself which of the two conflicting accounts of the alleged impending danger was correct, and his departure would not be construed as flight. To the success of this plan, however, an indispensable condition was that the servants should be left in the Palace and the flag kept flying. And these precautions were neglected. Every inmate joined the exodus – cooks, washerwomen, electricians, everybody. The shutters were then closed and, lest anyone should doubt that the King had really gone, and gone for good, his zealous adherents hauled down the Royal flag! The marines, barring access to the palace, had shut off the people of the city from this interesting spectacle. The house in which I live stands beside the palace and commands a view of the royal residence, the landing place, and the warships. From my balcony I witnessed the unwilling departure of the Royal Family, and the spontaneous flight of the Ministers and others who set a high price on their own lives and gratuitously credited the villagers with the instincts of ferocious savages. The King and Queen passed out amid the ominous silence of the Malissores and other faithful tribesmen in whose brains no intelligible picture of the day’s occurrences had yet been limned. Away in the offing hundreds of men, women, and children were huddled together in small torpedo boats where they spent the night in utter discomfort. All the Cabinet Ministers except M. Nogga departed. He and his wife refused to be separated from their fellow citizens, to be specially protected by marines or to believe the villagers of Shiak and Tirana capable of massacring their unarmed countrymen. Soon after this impressive scene was enacted, the “blood-thirsty” insurgents delegated their spokesman to Durazzo for the purpose of talking matters over with the Commission of Control. This body itself, however, was already on the way out to Shiak and met the delegates. A conference for the following day was agreed upon and peace fell upon Durazzo. Two and a half hours after his departure the King returned to the city, but his palace was empty and dark and there were no servants. Lamps from M. Nogga’s room and mine were lent him until the electricians arrived. A feeble attempt was then got up to launch the version that the King had never meant to abandon his city, but in the face of tell-tale facts, which could neither be denied nor explained away, this flimsy theory was abandoned. It is not necessary. The King’s action can be vindicated on other grounds. It was an error of judgment, for which most of the responsibility lies with others. The ensuing events may be summarily recounted. It was tardily discovered that the fanatical monsters who had struck fear to the hearts of the population were necessitous peasants who had nothing to eat or drink and scarcely anything to protect them from wind and weather. They had hoped the King’s arrival in Durazzo would usher in halcyon days and enable them to lead lives worth living, but they had been bitterly disappointed. Since then they had been told that a Moslem Sovereign would have effected what the Christian Prince never attempted, and that badly off as they now were, far worse things awaited them if the present régime endured. Hence they demanded the dethronement of Prince Wilhelm and the accession of a Mohammedan Prince. To the expostulations and suasion of the Commissions of Control they replied that blood having been shed by the King there was feud between him and them, feud which was abiding. But they protested that they were resolved to keep to the defensive and would not attack Durazzo. They gave up all their prisoners and behaved towards the Commission with marked courtesy. The prisoners on their return lauded the insurgents for their consideration towards them which in many cases bordered on tenderness. Of religious fanaticism there were no symptoms. Among the rebels there are many Christians, just as there is a large percentage of Moslems among their adversaries. On the advice of one set of his prompters the King, as soon as he was back in the palace, dismissed the Malissores to their homes in the North. A few days later he recalled them, together with six hundred more. This latter measure was adopted on the advice of his Minister Nogga who, from this time onward, appears to have won, as he had long deserved, the King’s full confidence. Nogga’s programme now began to be carried out by instalments. The Commission of Control, however, objected very strongly to the recall of the Malissores which had been decided and effected without their approval or knowledge, and they prophesied that sinister consequences would speedily ensue. Some of the foreign diplomatists concurred in this judgment, and the King was advised to send the highlanders away before they became restive. But this time the Sovereign held his ground. As soon as the Commission of Control had had its decisive talk with the insurgents and announced that it had failed to induce them to disperse, M. Nogga proposed that the Malissores, who had all been meanwhile enrolled as gendarmes, should be equipped and sent simultaneously with contingents from Alessio, Fieri, and Elbassan to surround, without actually attacking, the rebels, with whom negotiations might be profitably begun. In this the King acquiesced. But once more the Commission of Control, which would fain abolish the Cabinet and administer the country, opened its mind to him on the subject of the dangers involved in such an enterprise which, to their thinking, connoted civil war, bitter religious strife, disaffection, and probably defeat, followed by anarchy. “Fatal” was the adjective used by one of the Commissioners to the King to characterise the consequences he foretold. And when Finance Minister Nogga requested the Commission to open a credit for the equipment of the native forces, he was told that it could not be done because it was needless and baleful seeing that the insurgents, if time enough were given them, would return to their homes peacefully. The Minister insisted, pointing out that, as the Powers had refused to send international troops to defend the Prince and restore order in the country, it would ill become them to withhold from the Prince’s Government the funds which would enable it to do the work itself. After heated discussions, the Commission yielded, but not before the Ministers had intimated that they must lay the matter before the Sovereign and draw the practical consequences from the refusal. And now the plan put forward by Nogga is accepted, to bring tribesmen from Fieri, Alessio, Elbassan, isolate the disaffected villages, and try the virtue of suasion reinforced by a deterrent on the malcontents. The command of the forces has been given to Colonel Thomson, a Dutch officer, whose dismissal is now demanded for his unjustifiable breach of international law in arresting two Italian subjects. To sum up: Albania is for the moment a political Slough of Despond in which Nationalists, Catholics, Moslems, Bek Tashis, Beys, Pashas, demi-serfs, European Commissioners, Cabinet Ministers, Dutch Officers, foreign diplomatists, insurgents, and gendarmes are floundering about pêle-mêle, not knowing what they or their neighbours are doing. And so long as the causes of this chaotic tangle continue to be operative, the effects will necessarily continue to make themselves felt. To attempt to build up a self-sufficing State under the actual conditions, most of which Europe has deliberately imposed, is like trying to twist a rope of sand. Albania in its present plight may be likened to a drop of water imprisoned in a crystal, complete in itself, but shut up in a hard, impassable medium where it can neither expand into vapour nor harden into ice. And Prince Wilhelm’s function is to gaze at this crystal steadfastly and feast his soul on the visions and potentialities that unfold themselves to his inner sight as he contemplates it. It is not given him to penetrate the crystal, neither can he modify the water-drop. E. J. Dillon (1) One of the few writers who appears to have gauged rightly the trend of Abdul Hamid’s Albanian policies is Louis Jaray (cf. Questions Diplomatiques et Coloniales, No. 411). (2) These and other valuable suggestions were embodied in a detailed programme which M. Philip Nogga drew up for the Prince zu Wied and presented to him in Germany. Writing with the limited knowledge of an outsider, I feel disposed to regard these recommendations as calculated to solve most of the problems which the Prince was free to tackle. (3) The way to approach this delicate task, and perhaps to accomplish it, was pointed out by M. Nogga in the memorandum already alluded to, which he gave the Prince zu Wied before his accession. (4) I have read it. [E. J. Dillon, The Albanian Tangle, in: Fortnightly Review, London, n.s. DLXXI (1 July 1914), p. 1 28]

Essad Pasha Toptani in exile in London. Photo by

Manuel from the French periodical L’Illustration,

Paris, 2 December 1916.

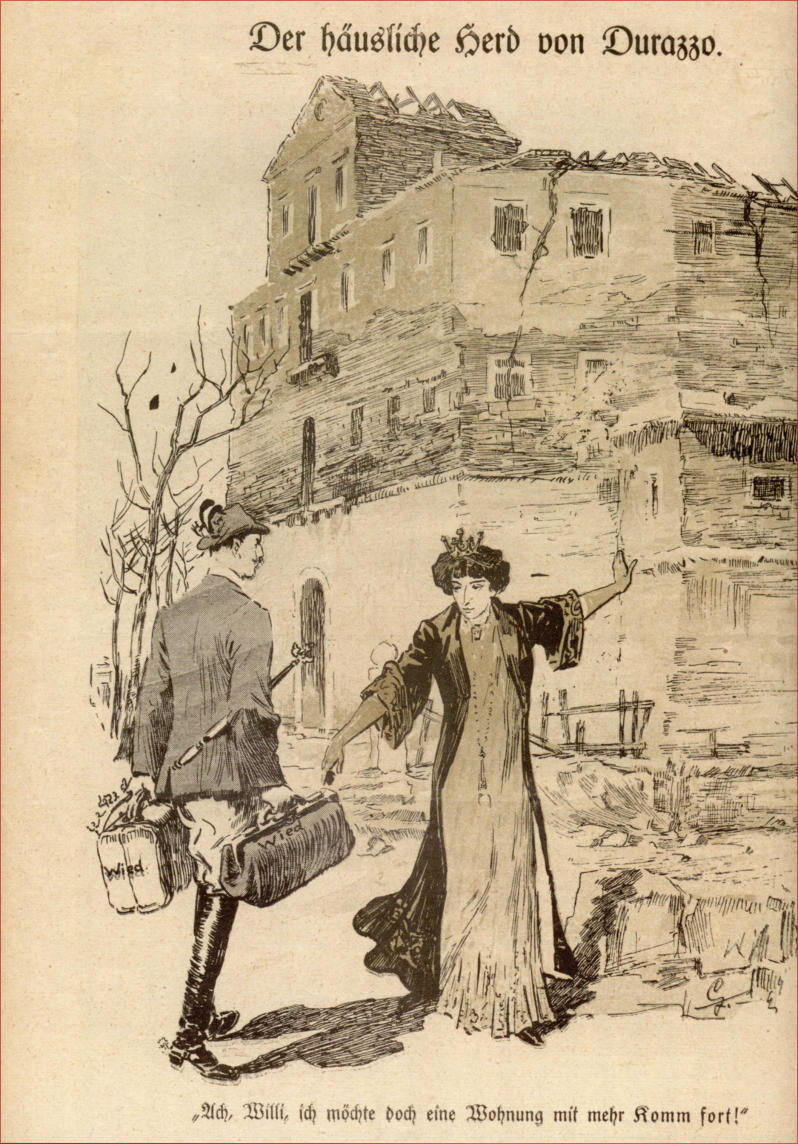

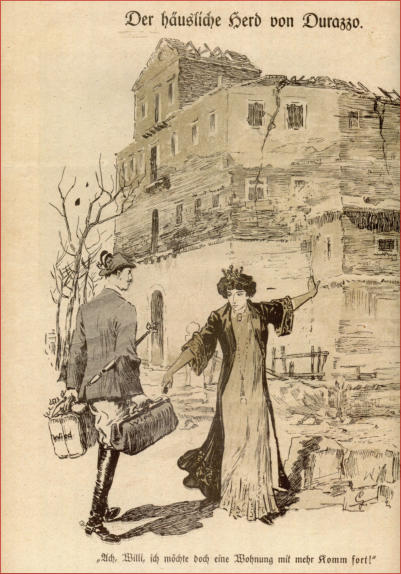

Home, Sweet Home in Durrës. “Ach, Willy, I’d prefer a

home with more ‘comfort’ (i.e. come forth!)”. Sketch by

Fritz Gehrke published in the German satirical

magazine ULK, Berlin, 13 February 1914

| Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact |