| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

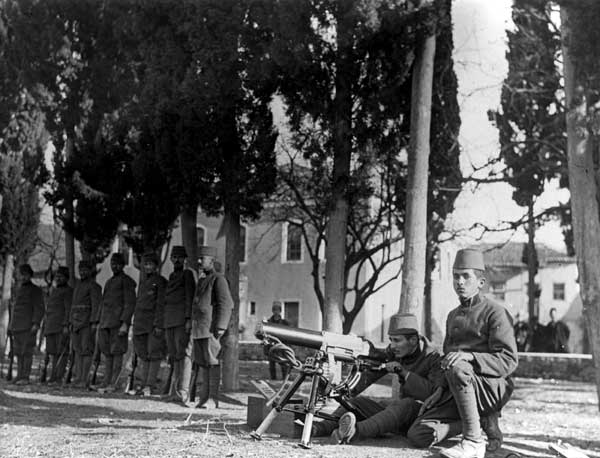

![]()

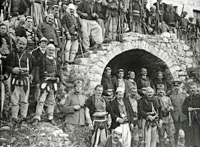

Albanian fighters in Durrës, 1914

1914

Duncan Heaton-Armstrong:

An Uprising in the Six-Month KingdomBetween January and August 1914, Irish Captain Duncan Heaton-Armstrong (1886-1969) held the position of ‘private secretary and comptroller of the private purse’ to Prince Wilhelm zu Wied (1876-1945) who had been selected by the Great Powers to assume the throne of independent Albania. He accompanied the monarch (Alb. mbret) to Albania and was with him during the intrigues of Essad Pasha and the Muslim uprising in central Albania, one of the factors that led to the Prince’s withdrawal from the country and the fall of the so-called six-month kingdom on the eve of the First World War.

Duncan Heaton-Armstrong

in Durrës, 1914

It was now May and the state of Epirus had been going steadily from bad to worse since the day of the Mbret’s arrival, so something serious had to be done to regain the affected districts for the Albanian Crown. The Great Powers, who had so generously fixed and guaranteed our frontiers, did not consider it part of their duty or business to protect them; so they left this difficult task to their unfortunate dupe, the Mbret “by the Grace of the European Concert”. The royal forces in the South consisted of some 2,500 gendarmes under Dutch and native officers and several thousand loyal Southerners, whose local leaders were supposed to cooperate with the regular forces. Attached to these irregular bands were a Captain Ghilardi (late of the Austrian Army) and an American, both of whom did excellent work later on in the year with a mixed detachment of native and Bulgarian “Komitadjis” (an outlaw or brigand).

The Royal forces had put up a good fight but could no longer hold their own against the Epirotes, whose troops were not only superior in numbers to our own, but also better equipped and organised by Greek officers, besides which they had a certain number of fairly modern field guns at their disposal. In Durazzo it was openly said that the Greek army was assisting the Epirotes and that this was the reason that they were so successful in driving us out of their country. Whether this was true or not, I don’t know, but it is certain that the Epirote movement was engineered from Greece and received more than moral support from the Greek Government. Many of the insurgents killed or taken prisoner were wearing Greek uniforms, minus the distinctive badges in most cases, and the guns are also reported to have been of Greek origin. Anyway, to make a long story short, our forces had to fall back, and fighting almost continually, were gradually forced north by the enemy.

The King and Council of Ministers had many a serious debate upon this subject. Colonel Thomson, the second in command of the Gendarmerie Mission, was of the opinion that the only way of getting back the Epirus was by diplomacy. As he had a shrewd suspicion that we were up against something stronger than we could tackle with our small and ill-equipped forces, he even went so far in backing his opinion that he attempted to start negotiations on his own, when he was Commandant of the Southern armies. The ministers and advisers were of course indignant at this and Thomson was recalled to Durazzo to explain his conduct. Essad Pasha, as Minister for War, was opposed to any compromise with the insurgents and assured the Mbret that the rebellion could easily be put down by force of arms; he carried the cabinet with him and it was decided to set to work in earnest!

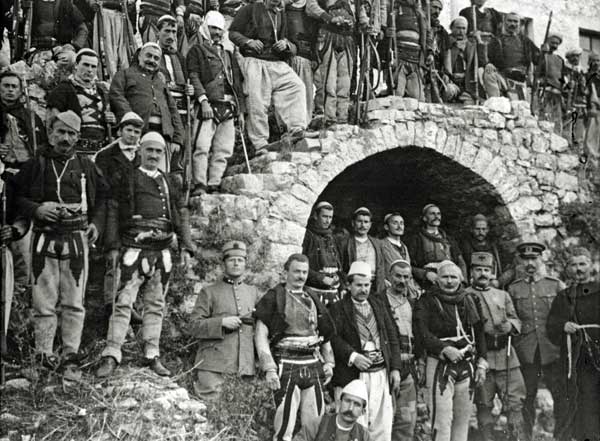

Machine guns from Austria,

spring 1914The Government had purchased several thousand modern military rifles in Italy, machine and mountain guns in Austria and now thought itself strong enough to conquer the greater part of the world. The Mahommedan population of central Albania was to be armed and with this imposing new army behind him, Essad Pasha hoped to sweep all before him; at least he said that he would. Although Essad had been a general in the Turkish army and ought to have known at least something about soldiering, it never seems to have struck him that it would be a good thing to put some sort of discipline into these untrained hordes before starting out on his expedition. Essad’s position was becoming very unpleasant, as owing to his murky past, everybody’s hand was against him and everything he did was doomed to failure owing to the active or passive resistance of his enemies. Most astounding stories of his disloyalty and double-dealing were whispered in the bazaars and cafes, from where they were brought to the palace. Everything was done to collect evidence to prove his dishonesty, but as far as I know no really damning evidence could be found against him, though everybody felt convinced that he was guilty. In this the Italians must be excepted as they, to then end, believed Essad to have been the victim of an Austrian conspiracy.

On the 8th of May he tendered his resignation on the ground that his personal enemies made all government impossible, while he remained in the cabinet. He told the King that he knew all the stories that had been circulated about him and that there was not a word of truth in any of them. He offered to go abroad and to remain in America for three or four years, to show the King his honest intentions, and added that he had given the King his word to serve him loyally and that if he had a thousand souls, they would all be at his sovereign’s disposal. At this interview Captain Castoldi was, I believe, present and acted as interpreter. For some reason unknown, the Mbret refused to accept the Minister’s resignation and coaxed and flattered him into retaining the office, which he was willing to give up and everybody considered him unfitted for. I have never understood why the King did not jump at this opportunity of ridding himself of Essad, without offending the great man. Considering the way he treated him only ten days later, the King cannot have had any great liking for him!

So Essad remained at his post and the central Albanians were armed. Long caravans of ponies left Durazzo for the interior, laden with rifles and enormous quantities of ammunition. Hardly had the arms and stores been distributed, when rumours reached us that the very people we had armed had unanimously refused to march South, or in fact have anything at all to do with the whole expedition against the Epirotes, “as they did not wish to kill their brothers!” Essad Pasha sallied forth to visit the affected districts - Shjak, Tirana, Kavaya, etc - and after a few days returned to headquarters. He reported that the movement was not serious and had been caused by the tactlessness of some minor officials and assured the King that he had put everything in order, so that the people were now willing to march.

As Essad, whatever else he may have been, was an uncommonly clever man, he must have seen and heard enough during his tour to show him what was happening in the country, so it can only be presumed that he deliberately made a false report to his royal master, for some reasons of his own. In spite of his assurances that all was well, most disquieting news kept coming in from the surrounding villages; on the 17th of May the King received an urgent message from Shjak (only about seven kilometres from Durazzo), asking for strong reinforcements, as the town was surrounded by insurgents and could not hold out if attacked. As Shjak was at this time garrisoned by about 200 “Royal” men from Kruja, one of Essad Pasha’s strongholds, the telegram was not taken too seriously and in spite of long discussions, nothing happened that night and Shjak was left to look after itself as best it could.

Among our numerous informants there was one who insisted that the Epirus expedition had nothing whatsoever to do with the rebellion, but that this was due entirely to agrarian causes. He told us that he knew for a fact that the peasants had only awaited such an opportunity to throw off the yoke of their oppressors, the beys, who owned the land and that they wanted to get rid of “Essad’s tyrannical government”. As I was all along certain that the Mbret was not being kept properly “au courant” by his ministers, who, through ignorance of the real state of affairs or some treasonable purposes of their own, continued to paint the situation in a rosy hue, I worried him, till he gave me his sanction to ride over to the insurgents next day, to have a look at them and, if possible, to find out what the trouble was about. Officially he had nothing to do with my expedition, as he did not want to take any responsibility and there was of course a chance of my getting into trouble. He could not be sure that I would not commit some “faux pas”, which, if I went officially, might have caused the government endless complications. So it was decided that I should go in plain clothes; nobody was told of my intentions, as gossip was the curse of Durazzo and it is always well to hold one’s tongue, till an experiment has succeeded.

It was about 7 o’clock on the morning of the 18th May, when I set out on my little native pony to have a look at the insurgents; the King and Queen had ridden out just before me and I followed behind their escort, to make certain arrangements with von Trotha, in case of accidents. Outside the town we separated, the royal cavalcade keeping to the right, close to the seashore, whilst I continued on the Tirana road. As I jogged along, I wondered what was going to come of this expedition and felt elated at getting the chance of doing something out of the common. As a precaution I had taken an automatic pistol with me and, though I did not intend using it, whatever might happen, it gave me a wonderful feeling of safety and self-confidence. (It must not be supposed that any noble motives urged me not to make use of my pistol; the truth is that I had never fired a shot out of it and therefore did not wish anybody to see my lack of skill.)

The first stretch of the road leads across the Durazzo swamps, which are fairly dry round here and overgrown with high, thick scrub; then come the heights of Raspul and once these are passed, the road again follows a valley, the greater part of which is under cultivation. I kept my eyes open on the way, expecting some signs of warlike activity, but everything appeared to be perfectly peaceful and the peasants were at work in their fields as usual. At Shjak I found a strong gendarmerie detachment guarding the bridge over the river. The village was full of armed men, the Kruja contingent, and the oriental street life was going on as if there were no enemy within a hundred miles of the place; however I noticed that the people appeared to be very much surprised at the arrival of a solitary European. At the Governor’s house I found that eminently respectable official, the officer in charge of the gendarmerie detachment and some of the village notables, lounging out of a first floor window. They could not understand how I had got through the rebels’ lines and I found it difficult to convince them that the road to Durazzo was clear of insurgents and that the country people I had met, were not even armed. A man, who spoke Italian, acted as Interpreter and through him the “Kaimakam” advised me to turn back before it was too late; under no circumstances was I to go any further, as “our scouts had seen a strong rebel detachment on the main road, not ten minutes walk from where we stood” and I would certainly be killed, or at least taken prisoner.

As it was evident that the worthies of Shjak were in a ridiculous state of panic and their information had so far proved to be wrong, I did not take their warnings too seriously and rode on. Somehow I felt that I would be as safe amongst the rebels as amongst our own people in Durazzo. At the end of ten minutes there was still no sign of any insurgents; the road from here onward serpentines up a long hill and on the top of this, some four kilometres from the village, I made a halt and had a look at the fertile valley on the other side of it. Through my field-glasses I soon spotted a strong detachment on the road, some two kilometres off; it consisted of about 2,000 men, most of whom were sitting about on the grass smoking, while about two companies were drawn up in line and appeared to be awaiting an order to move off.

As I did not appreciate the idea of riding into the midst of them without invitation and could not make up my mind as to what I was to do next, I just sat down by the side of the road and waited to see what they were going to undertake. I had not been here more than quarter of an hour, when two unarmed peasants emerged from a side-path. I stopped and questioned them as to whether they had seen any Komitadjis about. They looked at me suspiciously and did not answer my question but enquired first as to my nationality: was I Austrian or Serbian? I explained to them that I was British and this seemed to please them; the men’s faces brightened up and their manner became friendly. They now volunteered to personally conduct me to the nearest Komitadjis, who they said were very worthy men and friends of theirs.

On reaching a hollow, about a hundred yards from the road, we came on the enemy’s first picket; a sentry was posted behind a hedge on the sky-line to watch the Durazzo road, which could be seen nearly all the way, and his comrades were lying about on the grass. They did not stand up to receive me and were a murderous-looking lot of ruffians, all armed with modern rifles, large knives or bayonets and revolvers of various, mostly obsolete, patterns. Though their manner was not cordial and their appearance altogether against them, they answered my “Ngat jeta” (“Long life”, the usual Albanian greeting) quite civilly, so I dismounted, gave the pony to a boy to hold and sat down with them in the shade. My knowledge of the Albanian language is very limited, so we found some difficulty in understanding each other; this difficulty was bound to crop up, but I had not brought an interpreter with me, as I had by that time already discovered that the Albanians are even more suspicious of their own countrymen than they are of foreigners, and the presence of an interpreter might have spoiled my chances of hearing anything interesting. It must be admitted that our conversation was not at all brilliant and had to be limited to simple questions and answers, but I understood quite enough to make me feel certain that these rebels were no army of Essad Pasha’s. In fact many of them appeared to be out for his blood, as “they wanted to do away with him and all other landlords, whose sole occupation was that of taking the peasants’ money and then beating them!” Of course they unanimously condemned the ministry, which consisted of their old oppressors and did nothing to protect the peasant interests. From what they said, it was also evident that their religious fanaticism had been worked up as they kept on repeating “Mahommedans are good”, “Turks are good”, “Imams are good” and suchlike. I also understood them to complain that the schoolmasters were being paid higher salaries than the priests. As we later heard that this was one of the insurgents’ grievances, it seems probable that I understood right. One man considered Serbia the best country, but this appeared to be his private view and was not supported by his comrades. I told them who I was and that the King wanted to see his subjects contented and happy; to my great surprise they did not disagree with this at all and several of them murmured “Rroft Mbreti” fervently. From this first picket, I was moved on to another and then to a third and everywhere I was quite well received. I told the men of the large forces and artillery at Durazzo and pointed out the masts of some ships in the harbour, which could just be seen through my field-glasses, assuring them that they belonged to Italian men o’ war. As a matter of fact the Italian destroyer flotilla had put to sea in the early morning and had to be requested to return, by a wireless message, later on in the day. Although I knew this quite well, I thought it advisable to let the insurgents think that we were well prepared for any emergencies. We got on quite well with each other and my new friends gave me some of their bread and cheese, both of them the nastiest of their kind that I have ever tasted, and rolled cigarettes for me, which they shoved into my mouth and lit. I accepted everything that they chose to offer me and pretended to be enjoying myself thoroughly, though when I went away from the group for a moment I noticed that an armed man remained close by me all the time, which made me feel a little uncomfortable.

We arranged that a letter was to be written, which I was to take back to the King, and a man was despatched to the main body to find a scribe as none of the outpost company could write. While the man was away, I kept my eyes open, trying to see something more of the insurgents’ preparations. Before very long I discovered another detachment, not quite as strong as the first that I had seen on the road, which was moving to the right in the valley below me. This force was accompanied by a long string of pack-animals and a bugler, who from time to time gave vent to weird and brassy calls of his own. Altogether I must have seen close on three thousand men during the day. While we were awaiting the return of our emissary, two “Royal” (Essad Pasha’s Own) mounted gendarmes came our way; they joined our group and conversed in the most friendly manner imaginable with the enemy, with whom they appeared to be on visiting terms. I was much surprised at this and wondered what it all meant. Though the gendarmes knew who I was, they did not salute me or show respect, but glowered at me till they left us. It must be said to their credit that they looked a thousand times more villainous than the insurgents.

As time was getting on and the messenger did not return, I decided to make a move and told my friends to send the letter to Durazzo on the next day. I promised them that I would hand it to the King as soon as I received it. Shaking everybody heartily by the hand, to ensure their not shooting me as soon as my back was turned, I got on my pony and left them, accompanied by one of their number. Now they all stood up and saluted respectfully and so did all the other pickets that I passed on my way back to the road; arrived here, my escort, who seems to have been a sort of sergeant among his people, took leave of me and wished me a pleasant ride home. I did not stop to take the part of news-monger, when the worthies of Shjak surrounded me on my return to their village, and rode home at a jog trot.

It had been an interesting experience and, though I had not succeeded in finding out the names of the leaders of insurrection, I felt satisfied in my own mind that Essad was not one of them; besides this it appeared that the rising was not directed against the King’s person, but against his ministry. I decided that there were two principal causes for it - religious fanaticism and agrarian discontent.

When I got back to the Palace, I found everybody in a great state of excitement and the Mbret was so busy that he could not see me for some time. When I made my report to him, he did not appear to take the slightest interest in what I was telling him, or thank me for my trouble. This was rather disheartening, as I was under the impression that I had got some quite useful information for him and done a good day’s work.

The reason for everybody’s worried expression and the general state of nervous tension, I soon discovered to be the following: when I had left the King in the morning and the Royal cavalcade had kept close to the seashore on the sands, it had met with a rather painful experience. As they were galloping along quite peacefully, the officer in charge of the escort suddenly noticed the glint of rifle-barrels on the top of the Sasso Bianco (or White Cliff, a rocky hill which rises up close to the sea, about half-way to Kavaya, some six kilometres from Durazzo), some thousand yards, or so, in front. A halt was made and then a few figures could be distinguished moving about on the hill; there were only a few of them, but still! It seems probable that these men belonged to the extreme left of the line of pickets I visited during the day. After some deliberation, it was deemed advisable to retire, so the royal party turned tail and rode home at a good canter.

It is possible that, had they ridden on, without taking any notice of the insurgents, or had the King ridden up to them and spoken to them, the whole rebellion might have fizzled out and so all the useless bloodshed might have been avoided! In retiring as he did the King showed weakness; it is true that he was only following the advice of the aide-de-camp, who was supposed to know the ways of his countrymen, but all the same, he ought to have taken the bull by the horns and attempted to do something. Doubtless the insurgents presumed that they had succeeded in frightening him and the tale of their victory probably went the length and breadth of the country before that evening. Essad Pasha was immediately sent for and cross-examined; he still painted everything in rosy colours and laughed at the incident. He did not believe that there was any danger of a serious rising and made several palpably false statements. Anyway the King’s interview with him was so unsatisfactory, that by the time that I got home in the afternoon, nearly everybody was firmly convinced that Essad was a traitor, and that Durazzo would be taken by his supporters during the night.

No one listened to what I had to tell, as it was considered quite certain that Essad was the root of all evil; only Castoldi was interested in it, though he too was very disturbed that day. Perhaps he knew what we only suspected: that Essad Pasha was hand in glove with the Italian government, and he may have been afraid that unpleasant disclosures might be made, if steps were taken to break the Italians’ protege.

In the course of the evening things became rather mixed and nobody knew what to expect next. Durazzo was divided into two rival camps; nearly everybody was against the Minister for War and thought that he was going to undertake a coup de main during the night, get possession of the town and force the King to leave the country. The Italians and a small band of his retainers supported him loyally, but were in the minority. At a late hour we heard that Essad Pasha had ordered the Dutch Commandant of the town, Major Johan Sluys, to hand over the guns to an unknown new man, whom he had nominated as Commandant of the artillery. When this news spread abroad, it created a panic as people took this to be a sure sign that Essad was going to play some hanky-panky during the night. As Essad’s nominee was an Italian by origin, the Austrians naturally enough did not attempt to pacify the people, so the feeling in the town became more and more nervous as time went on. It was rumoured that Captain Moltedo, the officer in question, was in Essad’s pay and as the King had absolute confidence in the Dutchman, he did not confirm Moltedo’s appointment. Essad Pasha and Major Sluys almost came to blows over this incident.

To show how excited people were that night it is sufficient to tell the following story, which was circulated after the above-mentioned interview and believed by everybody, though nobody knew who had started it and it seems incredible - even for Albania! It is said that when Sluys visited Essad’s house to protest against Moltedo’s appointment, Essad ordered one of his retainers to put some poison into the major’s coffee; the man is supposed to have refused to do so, saying that he would not mind shooting him, but that to poison a man was beneath his dignity. Essad waited till the Major had left and then shot his servant dead; as there were naturally no witnesses to this domestic disturbance and no corpse was found on the premises some hours later, the whole story was doubtlessly a fabrication.

As far as I remember, the outcome of the King’s decision to support Major Sluys was the resignation of the Minister for War, who felt himself slighted. Everybody was glad to hear that the artillery would remain in reliable hands and flocked round the popular Dutch officer. Our garrison at this time consisted of about a hundred gendarmes, who however could not be entirely relied upon, as they were mostly natives of the affected districts and had joined the force before the King’s arrival, when Essad was still in the saddle. As a “precautionary measure”, Major Sluys armed about 150 Nationalists and other loyalists in the town, thus raising our armed forces to roughly 250 men.

In the course of the evening a plot was formed to draw Essad’s fangs; as a matter of fact the plot was so neatly hidden, that the proceedings later on in the night took quite a legal aspect.

In Albania it is customary for a gentleman to keep a certain number of armed followers always handy, partly to protect him from the emissaries of his enemies and partly to impress the population with his power and importance. As Durazzo was now supposed to be a part of Europe, most of the notables had limited their number of their retinue to two or three men. Essad however did not take part in this general demobilisation, but kept a villainous-looking company of cut-throats; some at his house and the main body in an old Venetian tower on the hill. There were supposed to be about a hundred and twenty of them altogether; quite an imposing force and certainly the most warlike people in the town. As Essad was suspected of harbouring treasonable designs, these men naturally constituted a grave danger to the peace of the town. It was therefore decided to disarm them and render them harmless; Essad was to be charged with keeping a private army, which, people said, was in itself illegal and should he offer resistance, he was to be taken, dead or alive. The undertaking was planned and organised by Nationalists and foreigners, most of whom were in the service of the Albanian government. As things turned out, I am glad to say that I had nothing to do with it, though had I known anything about it, I would probably have joined in, as I honestly believed that the King could do nothing as long as Essad remained in the country. I spent the evening in the house, looking after the Queen and the ladies-in-waiting, who were staying up, as there was no doubt that something exciting was going to happen during the night. The general belief was, as I have already mentioned, that the town would be attacked; this view I could not share, as I felt certain that the rebels were not Essad’s men, in spite of their friendliness with the mounted gendarmes.

At about 11 o’clock I saw Faik Bey Konitza from my window and called out to him to ask him what was happening in the town; his answer: “Nothing yet!” was the first indication we got that something was going to be undertaken by our people. The King had a very busy time, as ministers and other officials kept coming in to bother him; the Italian destroyer flotilla arrived and the senior officer came to enquire what he could do for us. A signal of distress was arranged with him, on seeing which the ships in the harbour were to land detachments, to protect the Palace. Worn out with worry, the King seems to have gone to sleep in his study - anyway he did not hear a gun being brought through the garden, right under his window, at about midnight. The Queen, ladies, Ekrem and I, still blissfully ignorant of what was going on all round, amused ourselves as best we could and awaited developments. When Sami Bey had ushered out the King’s last visitor, he had himself retired to his house in the town, as usual; as he was Essad’s son-in-law some of us thought his conduct very suspicious and imagined that he had gone to Essad’s house to plot with him. As it turned out afterwards Sami, who did not believe in his father-in-law’s guilt or the probability of a night attack, acted in perfectly good faith and spent the rest of the night in innocent and refreshing sleep; even the firing of the gun did not disturb his slumbers.

At last, at about three o’clock in the morning, a bey came to tell us about the plot and warned the Queen that there would probably be some firing later on, as he thought that Essad would resist arrest; it was a chilly night and he was glad to get a cup of coffee before setting out again to rejoin Major Sluys. As dawn was breaking, we heard a couple of rifle shots in the distance, which were followed by a fusillade; then there was a loud report, which woke up all the innocents in the town and rattled the window panes. So the gun was at work! A second and third shot followed in quick succession and then everything was still again. After the first shots I ran to the King, who was much disturbed by the shooting and did not know what was happening. I told him what I knew and he sent me to signal to the ships from the top balcony; this was a wise precaution, as we did not know whether the arrest would be successful and, had Essad been victorious, there might have been severe trouble in the town. Within a quarter of an hour sailors were landed and took up defensive positions in the garden and by the main approaches from the town. However peace had already been restored and the first warriors were returning from the “battle”, to bring us the news of Essad’s surrender. In due course, Major Sluys who had been in charge of the “arrest”, arrived at the Palace to make a verbal report to the King on the night’s happenings; the following is roughly what he said:

“It was brought to my notice that Essad Pasha kept a large body-guard of armed men in Durazzo. As amongst his retainers there were men of notorious character, such as Osman Bali, and as Essad himself is suspected of attempting to overthrow the Government; I, as Commandant of the town, felt it my duty to break up the gang and demand its immediate surrender. I ordered Essad’s house to be surrounded and had a gun trained on it from a suitable position behind the Palace; I called upon Essad’s men to lay down their arms and as they were about to comply with my order, their master appeared on the scene and asked me who had authorised me to give the order. When I told him that I had given the order on my own responsibility, he called upon his men to take up their arms again and prepare for resistance. A shot was fired and in the ensuing volleys one of our men was wounded. As I did not wish to endanger the lives of our men, I ordered the gun to open fire. The first shot blew a hole in the roof of the house and after the third, which burst in Essad Pasha’s bedroom, he had nothing left but to surrender.” Major Sluys now wanted to know what he was to do: was Essad to be lodged in the gaol, on board the Austrian cruiser which had been offered for this purpose, or what else was to be done with him?

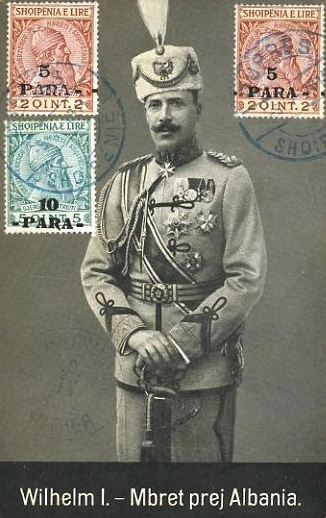

The Albanian monarch,

Wilhelm zu Wied.As the King had only heard of the plot against Essad after it had already been carried out, he did not now know what to do with him; he could not even make up his mind whether he was to arrest him formally or not. He felt that the War Minister had been wronged but was not strong enough to strike out on a course of his own. Had no outside influence been brought to bear on him, it is probable that he would have had Essad brought to the palace as a free man; however outside influence was brought to bear on him and after a lengthy discussion, it was decided to send Essad on board the Austro-Hungarian cruiser, “Szigetvar”. The Austrian authorities had promised to deliver him up, if called upon to do so by the King. Major Sluys had hardly left the house when the King, urged by the Queen, changed his mind, deciding to send Essad to the prison instead. I was sent to notify the Major of the King’s decision. On my return to the palace I found that new influences had been at work during my absence and that the original order was to be carried out after all; so I had to get hold of Sluys whose remarks about this continual change of plan were rather sarcastic. I did not like the idea of sending a political prisoner onto a foreign warship, as I was afraid of renewed Austro-Italian differences on the subject; besides it struck me as rather irregular that a political prisoner should be, practically, extradited and then handed back to the authorities of his own country by a foreign power. Of course it did not make any great difference to anybody whether I approved or disapproved of the scheme!

At 9 o’clock an Austro-Italian naval detachment was ready to escort me up to Essad Pasha’s house, where I was to arrest him and bring him back safely to the landing-stage. The dragomen from the Austrian and Italian legations accompanied me to act as interpreters and to see fair play. It was a most unpleasant business and, as I was tired after my ride to the insurgents on the previous day and a night out of bed, I did not appreciate it at all, particularly as I thought it probable that Essad’s bodyguard, which had surrendered, but not yet been disarmed, would open fire on us as soon as we got through the great gateway, close to the house. As I was walking in front, I felt anything but brave.

On arriving at the house, the two dragomen and I went up to the door, more than expecting a volley to send us into the next world; the Italian dragoman, I suppose, knew that we were safe enough and was therefore not surprised when the door was immediately opened to us. In the hall stood Essad and his wife, with their retainers all round them - and the Court Doctor Berghausen. What the latter was doing here we could not find out; probably he had only come on some pretext, in order to watch the arrest and join the procession, as he liked to appear before the public as a person of great importance, he was much annoyed that I would not allow him to accompany us down to the landing-stage. Essad, who seemed to know what to expect, was not at all surprised when I informed him that he was under arrest and would have to accompany me down to the landing-stage, where he would be handed over to the commander of the Austrian cruiser. His wife, who was devoted to him, begged to be permitted to go with him, and as this did not clash with my orders, and appeared to be a reasonable request, I without hesitation permitted her to do so. Essad’s enemies afterwards told me that he only took his wife with him as a protection; the Albanians are very chivalrous and would hesitate to murder a man in the presence of his wife. As I had reason to believe that Essad’s life was in danger, the Italian commander of the escort and I took the couple between us. I did not want to take Essad through the palace garden, and had intended going down to the harbour through the town, the shorter way. However Essad was very anxious not to go through the town and as I had no definite instructions we took the garden route. Later on in the day I discovered that three men had been posted at windows, overlooking the road we were expected to take, and that Essad would have been murdered had he walked into the trap. The conspirators were very disappointed at the turn of events and bore me some ill-will, saying that I had compromised the King by bringing Essad through his garden. Probably Essad had received a warning that he would not reach the harbour alive if he went through the town; there cannot have been any other reasons for his preferring the indirect route. We met very few people on the way, as we were expected to pass through the town, and the square in front of the palace had been cleared by the police; as we reached this and crossed it to the landing stage, the crowds assembled behind the gateway leading to the town set up a howl, so I kept well in front of Essad, to prevent anybody from taking a shot at hirn. I was criticised for bringing him the way I did, but I am glad that I did so, as it is certain that he would have been murdered, had we gone through the town. At the landing-stage I handed him over to Captain Schmidt of the “Szigetvar”; here Essad assured me that he had been loyal to the throne throughout and that he was the victim of an intrigue. From the time of his arrest till we parted Company he had behaved with great dignity and sang-froid under most trying circumstances, so in spite of the fact that I believed him to be a traitor, I had to admire his conduct and feel sympathy for him in his fall. A launch was waiting for him; he got in and so disappeared, officially at least, from the public life of the Six Month Kingdom!

As he was leaving I noticed two of his retainers, who had accompanied him with his hand-luggage, trying to get away unnoticed in the crowd; I caught them up before they had gone very far, arrested them and handed them over to the Palace Guard, who transferred them to the congenial atmosphere of the gaol. They were a couple of very nasty-looking blackguards and as everybody connected with Essad was now suspected of being a criminal, their disappearance may have saved them from the vengeance of the mob!

During the day everything was upside down: ministers quarrelled in the street, surrounded by riff-raff; the cabinet resigned and the palace was strongly guarded by foreign sailors; they stood about the passages and stairs for hours on end, guarding the entrances and doors of half the rooms in the house. Why they had been called in, or against whom, nobody exactly knew and the Italians laughed at such elaborate precautions! After a time it was considered sufficient for them to take up the duties of the palace guards, who, though they had behaved irreproachably all the time, were considered too unreliable; so our corridors were evacuated and the house once again belonged to us.

Essad’s house was searched and several trunks full of documents were taken from there to the police-station, where they remained, I believe for ever afterwards without being opened. Several other houses, belonging to Essad’s friends, were also searched and numerous arrests were made by the over-zealous police; however no shred of evidence could be found against anybody and most of the victims were released later on in the day. In the afternoon great discussions took place as to what we were to do with Essad, now that we had got him; some proposed that he should get a fair trial, enthusiasts wanted him to be brought back and hanged in the square, and the Italians considered that he should be permitted to retire from public life and to live in Italy. I personally proposed a court martial composed of foreign officers serving under the Albanian government; for instance von Trotha as president, Major Sluys and I as members.

To our great disgust, we were told next day that the Italians had prevailed and that Essad would be sent into exile, without a trial. I was annoyed at this decision as I failed to see how the Mbret had the right to send a man into exile, whose guilt had not been proved. I told the King that he was hastening his own downfall by allowing Essad to go abroad, from where he was certain to take vengeance for the manner in which he had been treated. I felt certain that Essad was guilty and wanted it proved; in that case a court would have been justified in sentencing him to death and so the whole matter would have ended. As it was, the King’s decision, which neither acquitted nor condemned his late most powerful minister, made an exceedingly bad impression on his loyal subjects; they considered that the King had robbed them of their prey and had allowed himself to be outwitted by the Italian diplomats, who were generally believed to be Essad Pasha’s allies.

At midday I was sent on board the “Szigetvar” to communicate the Mbret’s decision to the victim and also to search his luggage and confiscate all documents in his possession, a useless precaution, as a man of Essad’s intelligence would not have been fool enough to carry incriminating papers about with him! According to my instructions to seize all papers, I brought away three attache-cases full, which were sealed by him and delivered to the Mbret on my return to the palace. One of my last official duties before leaving Durazzo in August, was to return these cases, the seals unbroken, to Essad Pasha’s address in Italy; as they were never looked into, what on earth was the use of having sent me to take them from him?

Essad also had to sign a promise that he would not attempt to return to the country without the Mbret’s permission to do so, and that he would not in any manner, privately or publicly, mix himself up in Albanian politics or intrigues against the throne; this promise he signed without any hesitation. He again assured me of his loyalty and said that the King would regret his hasty action and recall him, when he would willingly return to work for the good of his country. We parted friends and Essad Pasha left for the Italian port of Bari in an Italian ship late in the afternoon. I wonder whether he took it all so well because he knew that the King would not be able to hold out much longer and that he himself would soon be in the saddle again?

That evening there was a new excitement in the town; in fact half the population thought that the end had come! The two hundred men of Kruja had arrived from Shjak; why nobody exactly knew as they had received no orders to come to Durazzo; it was generally believed that they were Essad’s most devoted followers and that they had come to wreak vengeance on the town. Ekrem Bey Libohova took a very serious view of this new complication and was of the opinion that the town was really in danger as long as these warriors were at large, so, in spite of their protestations of loyalty, they were locked up overnight in the school house, strongly guarded by Nationalist volunteers. Next morning they were released and, in spite of the rather curious treatment that they had received, made a loyal demonstration outside the palace, after which they were allowed to leave the town unmolested and return to their native district.

Essad Pasha ToptaniAlthough the Kruja men were safely under lock and key, it was thought advisable to arm our servants; I took the matter in hand, and putting von Trotha’s secretary, a non-commissioned officer in the German Foot Guards, in charge, I served out rifles and ammunition to all the men-servants. Practically all of them had served their time in the Austrian or German army, so they ought to have known how to handle a rifle! However they turned out to be a very second-rate lot of soldiers, as before I had finished arming them one of their number loosed off a round, the bullet burying itself in the wall, not far off the cook’s head. I cursed everybody heartily, told them not to load the rifles or play about with them and went upstairs; hardly had I joined the ladies when there was a second loud report, which fairly made us jump. I ran downstairs again and found a group of frightened retainers standing round the cook’s assistant, who, rifle in hand, was also shaking with fear and astonishment; he had let off his round into the ceiling, just underneath the corner where the ladies had been sitting. Von Trotha now appeared on the scene in a most unpleasant humour and gave the servants a lecture, in the course of which they heard as choice language as they had ever done while they were in the army. He then disarmed them all, with the exception of the native “Kavasses”, as their “protection” appeared to mean the untimely death of one of us before the arrival of an enemy.

This comedy was the last event of any interest during the evening; we sat up late, expecting further alarms, as rumours of threatening disturbances kept coming in, but nothing happened and at a late hour we retired to rest and slept undisturbed till next morning. Unfortunately the Essad incident was now closed; the King made the grave mistake of not having an immediate enquiry made into the whole matter. Had an efficient commission been brought into existence, it is probable that Major Sluys could have justified his action, besides which the charges of treason against Essad might have been gone into and perhaps proved to everybody’s satisfaction. As it was, the whole affair remained wrapped in mystery and nobody to this day knows exactly how it originally came about. On thinking the matter over quietly, I believe that foreign influences deserve most of the blame, though at the time I was under the impression that the plot was entirely of Nationalist origin.

The Mbret’s actions naturally enough led Essad’s supporters to believe that he had known all about the conspiracy against his minister and had approved of the bombardment of his house, and it is not to be wondered at that this made an exceedingly bad impression in the country. The foreign press had the same impression and eulogies were written about the Mbret’s “determination”, in ridding himself of his unruly minister. It was a bad affair, bungled from beginning to end and did the King’s cause a lot of harm. Had a proper enquiry been made into the matter, it seems certain that everybody could have been whitewashed, somehow, and in this case the Mbret would not have lost so much prestige among his subjects.

[Extract from: Duncan Heaton-Armstrong, The Six Month Kingdom: Albania 1914. Edited by Gervase Belfield and Bejtullah Destani, with an introduction by Gervase Belfield (London: I.B. Tauris, in association with the Centre for Albanian Studies 2005), p. 46-69.]

TOP