| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

![]()

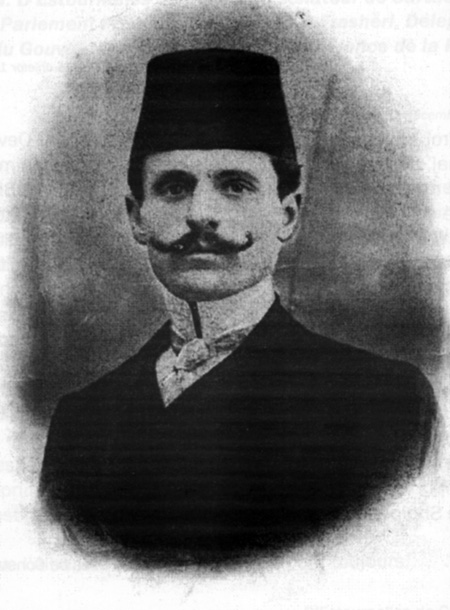

Mid’hat bey Frashëri.

1915

Mid’hat bey Frashëri:

The Epirus Question

- the Martyrdom of a PeopleAlbania declared its independence in November 1912, but the country’s southern border was long undefined. Fighting erupted, with Greek forces trying to get as much of the disputed territory as they could. An International Control Commission was created to define the Albanian-Greek border, and Greek forces were subsequently forced to withdraw to the present border, but not before wreaking terrible destruction on southern Albania and Chameria, now in northern Greece.

In “The Epirus Question,” published originally in French, Albanian publicist and political figure, Mid’hat bey Frashëri (1880-1949) vents his anti-Greek passions in denouncing the ravaging and destruction of much of southern Albania by Greek military and paramilitary forces, a calamity that he seems to have experienced at first hand.

Known by his pen name Lumo Skendo, Mid’hat bey Frashëri was the son of Rilindja politician and ideologist Abdyl bey Frashëri and nephew of the equally illustrious Naim bey Frashëri and Sami bey Frashëri. He is thought to have been born in Janina (Iôannina) and, from 1883, was raised in Istanbul where his family was the focus of the nationalist movement. From 1905 to 1910, having given up his studies of pharmacology, he worked for the Ottoman administration in the vilayet of Salonika. In July 1908, now using the pen name of Lumo Skendo, he began publishing the weekly newspaper “Lirija” (Freedom) in Salonika, which lasted until 1910. He presided over the Congress of Monastir in 1908, and in January of the following year began editing a monthly magazine entitled “Diturija” (Knowledge), an illustrated periodical of cultural, literary and scholarly interest.

Mid’hat bey’s political activities took on a more nationalist character during the Balkan Wars and the final collapse of the Ottoman Empire when Albania was on the verge of being carved up by its Balkan neighbours. After the declaration of independence in November 1912, he became his country’s first minister of public works, and later Albanian consul general in Belgrade and postmaster general. At the start of World War I, he was interned in Romania for a time, but after his release, he returned to publishing. Mid’hat bey resided in Lausanne for a time with his cousin Mehdi bey Frashëri, where he was author of a number of newspaper articles and essays. On 25 November 1920, he was appointed chairman of the Albanian delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, where he remained until 1922. In Paris he continued his journalistic activities in the French press to publicize Albania’s position in the postwar restructuring of Europe. He subsequently held other ministerial posts and was Albanian ambassador to Greece and to the United States from 1922 to 1926.

Under the Zog dictatorship, Mid’hat bey abandoned public life and opened a bookstore in Tirana in 1925. He himself possessed an exceptionally large private library of some 20,000 volumes, the largest collection in the country at the time. At the end of 1942, he re-entered the political arena, at the age of 62, to fight the Axis occupation, and was named leader of the republican resistance organization “Balli Kombëtar”. In the autumn of 1944, with the communist victory apparent in Albania, he fled to southern Italy. The early years of the cold war found Mid’hat bey Frashëri in the West trying to patch together a coalition of anticommunist opposition forces in Britain and the United States. In August 1949, he was elected as head of a Free Albania Committee. He died of a heart attack at the Lexington Hotel on Lexington Avenue in New York.

Crown Prince Constantine of Greece

entering Janina. 1913

To the Reader:

On the shores of the Adriatic in southern Europe, there is a country called Albania. Until 1912 it was part of Turkey-in-Europe. During the Balkan War, the country declared its independence at a national congress that assembled in Vlora on 28 November. The Conference of the Ambassadors in London confirmed its independence, declaring that Albania was a neutral State and placing it under the protection of the six Great Powers.

The population of this Albania was not much over one million. Another million and a half Albanians remained outside the borders of the Albanian State, and were divided up by the Greeks, Serbs and Montenegrins. The million inhabitants within the kingdom of Albania consist of Catholics, Orthodox and Muslims who want only to live their lives in peace under the European and Christian king that they wanted and who was finally selected for them by the Great Powers.

But the life and happiness of the Albanians on their little patch of land offended their neighbours - the Greeks, Serbs and Montenegrins, who coveted all of Albanian land, down to the last patch, and whose wish it was to have all Albanians disappear from the face of the earth.

In the following text, we will tell the story of one chapter in the history of this land lusted after by Albania’s very Christian neighbours. Our two rich and prosperous provinces in the south have been reduced to rubble. The entire population, who lived peacefully and wanted no more than to live on the land of their ancestors, has been decimated. Neutral Albania under the protection of the six Great Powers has been torn apart and ravaged by Greece. It is a crime without parallel because it is the result of perfidy and dishonesty. The catastrophe is not the result of a war. It is not in the heat of battle that our villages were reduced to ashes and our men (and women and children) were massacred. It was with composure and deliberate intent that these acts of inhumanity were carried out.

And yet, these horrors have been ignored, barely noticed. Very few people in the civilised world have been shocked by them. Some have even applauded and endeavoured to justify them as attributes of Greek civilisation.

The Epirus Question

In the summer of 1913, Zographos, the Greek Minister of Foreign Affairs, who was governor of Janina at the time, pronounced the following words of human kindness at a dinner given for Albanian leaders from Janina and other districts, words of divine grace: “Do not harbour any illusions. Even if we are forced to abandon Epirus, we will leave nothing behind but the soil. Everything growing on it will be razed.” (1)

Having learned in my childhood to believe that everything the Greeks said was lie and deceit, I regarded this, once again, as nothing but an empty threat. Yet Zographos proved to be a man of character and honesty in his profession as a freebooter. He kept his promise.

The Conference of the Ambassadors in London took no decision on Albania’s southern border. It decided to transfer the matter to an international commission that was to visit the region and establish the border in line with the ethnic composition of the regions in question. The commission soon arrived in Korça (Korytsa), composed of representatives of the six Great Powers. It travelled down the country from that town to the sea, passing through Kolonja, Përmet, Leskovik, Gjirokastra and Delvina. When it completed its work, it departed for Florence and drafted a protocol that confirmed the purely Albanian character of the districts it visited.

Greece used whatever tricks it could to deceive the commission, and indeed, the “Greeks” were in fine form here! In Kolonja, for example, the Greek authorities hastily carted purely Greek families in from other regions, and with great zeal endeavoured to get the commission to believe that the native population was Greek. A ridiculous comedy.

Another example of Greek trickery was played out in the village of Qinam in Kolonja where the commission was to arrive in the evening. The Greek authorities hung a bell in a tree to insinuate the presence of a church. Young children were brought in from far and wide to hold speeches. However, one of the kavasses working for the commission happened to be from the village of Qinam and revealed the dishonest and rather stupid trick of the Greek authorities. (2)

The whole time, telegrams and petitions poured in to inundate the Conference of the Ambassadors. Hundreds of thousands of Albanians living abroad, in Romania, Egypt and America, as well as the refugees in Vlora, all originally from the provinces of Korça and Gjirokastra, Christians for the most part, demanded unification with Albania, giving voice to their Albanian identity. These documents were duly registered in the Conference acts, but very few newspapers ventured to take them up.

Korça and Gjirokastra were thus accepted as regions to be returned to Albania. The population had demonstrated its will and the on-site commission had confirmed the purely Albanian character of the inhabitants. On the Albanian side of the border, there remained, south of Delvina, a dozen mixed villages of Greeks and Hellenized Albanians. On the other side of the border, from Cape Ftelia to Preveza and Janina, there were over one hundred thousand Albanians (most of whom in Chameria, a region inhabited by the best of them). This region was still in Greece.

If there was one side that was justified in complaining about this dispute, it should have been Albania and not Greece. All that Greece had to do was to accept the decision with grace and to submit to it. And indeed, in all appearances, that is what it seemed to do. In its Note of 8/21 February 1914, it informed the Great Powers that it had accepted their decision. But, as usual, the Greeks were up to no good. Deceit was the only course of action, where persuasion did not work.

Zographos was there and he had not forgotten his threat. In no way can the actions of Zographos be separated from those of the Greek Government. Even if Venizelos had been sincere, there is no doubt that he was acting in cahoots with Greek military troops under King Constantine. Zographos and Constantine needed to come up with some trick, and copied one used during the ephemeral autonomy of Gumuldjina. But if in the latter case, the comedy remained harmless, here things turned tragic and the so-called Epirotic Comedy left a long trail of blood in the annals of history.

The actions required were already put in place and Zographos had no need to disguise his intention of keeping Epirus, (3) and, if not, to abandon this part of Albania after having ravaged and destroyed all the fruits of the soil.

From the very start of their occupation, the Greeks endeavoured to set up “Sacred Bands,” i.e. Albanian volunteers who would support the union of Epirus and Greece. Young people were taken by force, terrorised by brutal officers and NCOs. Peaceful craftsmen and shopkeepers were plucked from their work and trained for the military. These were initially innocent goings-on to no one’s detriment. But Greece knew better than anyone else that it could not rely on the Albanians to keep Epirus. It needed to have recourse to other means. Firstly, it turned to its two friendly Powers and protectors, France and Russia, whose support and cooperation it swiftly acquired. But politics alone was insufficient if not backed up by military force. This force could not be recruited from within the country itself. After all, what Albanian would have fought to have his country annexed by Greece? It therefore used a little trick, in traditional Greek manner. Regular Greek troops under the command of their officers were badly disguised as local peasants, in Epirotic bands, i.e. as Albanians calling for union with Greece and willing to fight for this union.

When the districts of Epirus were to be evacuated, these soldiers, still under the command of their officers, appeared behind them and took possession of the regions with their weapons: rifles, ammunition, machine-guns and cannons.

The evacuation, or rather the pretence of the evacuation of Epirus began in Korça on 3 March 1914 (new style). An agreement was drawn up between the Greek colonel Condoulis and the Albanian major Mustafa. Our gendarmerie, organized by the Dutch Mission, took possession of the town of Korça to great rejoicing, both in the region and throughout Albania.

The evacuation was supposed to continue and everyone hoped that the country would be purged of the usurpers, and returned to and united with its motherland. But can one ever trust the promise or word of honour of a Greek? Here are a couple of facts serving to illustrate the history of the Epirus question and throwing some light on it. (4)

On 19 March (new style), the Greeks told our gendarmes to go and take possession of the village of Odriçan, near Frashër (kaza of Përmet), but the moment our men entered the village, the Greeks treacherously opened fire from the church. Officer Qani was wounded and twelve men were killed.

The previous day, 18 March, there was fighting in Radanj near Leskovik that the Greeks had evacuated and handed over to the Albanian gendarmerie. These same Greeks then returned and attacked our men. They were put to flight, with about 30 men being killed. The same day, to avenge their defeat, the Greeks put seven villagers to death, including a fourteen-year-old boy. The poor villagers found themselves in the hands of the Greeks in Leskovik to serve them as the horse and mule-drivers. Such is the honesty and loyalty of the Greeks.

Officially and formally they pretended to continue with the evacuation of Epirus, but in reality they were busy devastating and slaughtering. Zographos, Venizelos and their military establishment (or rather clique) snubbed their noses at the Great Powers. They were playing games. The Greeks were in their element and Europe pretended not to understand and, indeed, let out cries of admiration for Greek misdeeds.

The next day of the so-called evacuation of Korça, Greek correspondents spread rumours of a re-occupation of the town by the Greeks. Since the capital of the region had been handed over officially and in due form, no one suspected the plot drawn up by our southern neighbours. In Albania it was said at the time, and everyone believed it sincerely, that Greece would never commit such a perfidious act right under the noses of the six Great Powers who had signed the treaty in London and who should have shown at least some self-esteem, if nothing else. However, this is what happened:

On departing from Korça, the Greeks left behind some thirty sick men with two physicians, an officer and some soldiers to guard the sick. It was a small core of infection that we were wrong to put up with since Greek komitadjis slipped into the town and, on the night of 3 to 4 April, made an attempt to overthrow the authorities. The coup failed, easily put down by the inhabitants. The peril seemed to have passed when, on the fifth of the month, we learned that another band was approaching Korça. A pitched battle resulted, in which the attackers took flight and escaped southwards.

What had taken place?

Zographos and his clique were watching. The coup in Korça, prepared by Greeks foreign to the region, was supported by the Greek bishop of the town, a fanatic sectarian and a true komitadji, as are all the other priests forced upon us by the ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, real pests for the flocks they are supposed to guide. Following the defeat of the coup in Korça, the Greek Government took things over, convinced that the sword would be stronger than the cross. Three hundred fifty soldiers set out from Kastoria (a town situated south of Korça on the territory annexed by Greece) under the command of Greek officers, officers from the standing army of His Hellenic Majesty: Mavraza, Laza, Benapoli, Asterio, Ilia Papageorgiou. Add to these five officers a person of sinister appearance, a type of Quasimodo, Boussios, former Greek deputy in the Ottoman Parliament for Serfidje, and you will have the whole range of them. Before setting out on their march, these soldiers and officers received the blessing of the Greek Bishop of Kastoria. (5)

During the operations, the Greeks did not fail to commit atrocities. Villages were burned down, peaceful and innocent inhabitants, including women, had their throats cut or were burned alive, other villagers were taken by force to make believe there was an exodus of people fleeing from the Albanian Government, to empty the country and sow the seeds of misery. Among their crimes, mention may be made of the assassination of the Vlach priest, Papa Haralambi of Korça, whose throat was slit in cold blood, with those of his brother and cousin. This assassination of this dignitary caused great outrage.

And while such horrors, all a result of deceit, were being committed in Korça, the Greek newspapers were jubilant. They could not shower enough praise on the deed and were full of admiration for Greek sacrifice and patriotism. On 5 April, the Times announced that Korça was already in the hands of the Greeks. A few days later, the same newspaper, in its issue of 13 April, wrote the following: “…in the skirmish, Father Balamaci is said to have been killed or roughed up.” Imagine! The cowardly assassination of a priest dragged from his home is characterized as being “roughed up.”

But all the more disgusting is the racket caused by the Greeks to cover up their cowardice. All the bells went into action. In an unscrupulous and shameless manner, the Greeks cried assassination and at the same time, they spared nothing, nothing could escape their fury. Reading Greek newspapers published last year is a bewildering experience. In the 10 April 1914 issue of the Times, we read the following report:

“Athens, 9. Having disarmed the population, the Albanian gendarmerie carried out a general massacre. The Greek Government brought this fact to the attention of the Powers.”

This is all. To hear the Greeks, you would think that the Albanian authorities were massacring the Christians! But what astounds us most in the above-mentioned report is the reticence. In referring to the inhabitants of Korça, they use the term “Christians” whereas everywhere else to refer to the Orthodox Christians of Albania, the Greeks always use the word “Greeks.” This is insanity typical of our southern neighbours. For them, everything Orthodox is of necessity Greek. It is impossible for the Greeks to distinguish between their religion and their race. As such, they regard Orthodox Albanians simply as Greeks, as they have done the Bulgarians, Vlachs and Serbs until recently. (6)

In actual fact, as we have stated above, in all of Albania, as delimited by the conferences of London and Florence, there are no more than a dozen, partially Greek village, south of Delvina. Nowhere is there a single completely Greek village. I stress the word ‘single’ because the Greeks, who have no sense of scruples or decency, have always done their utmost to deceive public opinion.

On the other hand, there are over one hundred thousand Albanians in the regions extending from Cape Ftelia (the southern border of Albania) southwards down to Preveza and Arta.

But let us return to the Korça affair. Unfortunately the problem was not limited to the surroundings of Korça. The Greek scourge extended along the whole southern border, from Bilisht to the Adriatic Sea, passing through Leskovik, Përmet, Tepelena and Himara. The Albanian gendarmerie, under the command of Dutch officers, went to take possession of the districts that the Greeks were supposed to evacuate under the provisions of the Note of 8/21 February. Here the Greeks stated that they would abide by the decisions of the Powers on the Albanian border. But instead of simply taking possession of the region, our gendarmes were forced to engage in battle with Greek soldiers, who were more or less in disguise as Antartes (komitadjis).

We have no doubt whatsoever as to the real character of these so-called Antartes. Numerous people have testified that these Epirotes were actually no more than Greek soldiers or Cretan volunteers. The long report of the head of the Dutch mission in Albania, which we will give at the end of this text, is more proof than is needed. I currently have in my possession the statements of six Greeks, captured in Korça, weapons in hand, on 6 April 1914. All these men admitted that they were Greek soldiers and gave the number of their company and battalion. (7)

On 28 April (9 May) 1914, the author of these lines took part in an interview between the Dutch major Verhulst and some Epirot officers in Kolonja, southwest of Korça. I saw the three Greek officers, the highest ranking of whom was a captain called Tsipuro, in their Greek uniforms and army caps with insignia. As an irregular among the officers, there was a certain Stefo who claimed to be an Albanian, but whom we had no difficulty in identifying as a Greek, or rather a Greek-speaking Vlach from the village of Liskach in the Grammos region, territory annexed by Greece.

It was no mystery for anyone. Greece took great pains to abide by the decisions of the Powers, but in actual fact, it did not abide by them at all. Its resistance was made all the easier because the Powers were not inclined to insist on the decisions they had taken in London. Greece continued to postpone the date of its withdrawal from Epirus, and the Venizelos was in the meanwhile touring European capitals. They stated that the evacuation of Albania would begin on 18 December 1913, then on 18 January, and then on 18 February. Finally it was only on 3 March 1914 that a pseudo-withdrawal began (from the town of Korça). Confronted with Greece’s lack of goodwill, Albania was too weak and by no means in a position to seek justice by force of arms. It thus contented itself with returning the matter to the signatory Powers of the Conference of London.

As noted above, the goodwill was not at all as good as we would have wished. Venizelos had received promises on his tour and was hoping to keep southern Albania. Nonetheless, he had to keep up appearances because the Powers themselves wished to convey the impression that they were keeping faith with what they had signed - the ink was still fresh. The best was to let the two sides sort it out themselves. This meant defeat for tiny Albania, recently created, in face of a Greece that was five times the size and a century older. Not wanting to compromise its relations with its protectors, Greece now devised the Epirotic comedy. It would make the world believe that there was armed resistance to annexation by Albania! And to implement the project, the treacherous Zographos (8) was more than willing offered his services to the military clique. Soldiers, officers, ammunition, weapons and money were put at his disposal. In addition to this, was a band of Cretan criminals, thugs and former convicts from all regions of Greece who arrived to join the ranks of the legions and, in haughty impudence, call themselves “sacred”!

The whole lot of them were called Epirotes: the Greeks, the men of Creta, Corfu, Zakynthos, all pretending to be native Albanians of Epirus! Despite all the evidence of the trick, we read the following lines in the newspaper Times of 26 April 1914: (9)

“The Greek Government has given its assurances that it has never endeavoured to hinder the activities of the Albanian Government and categorically denies that several hundred regular troops have joined the uprising.”

Risum teneatis?

These Epirotes (from Crete), the sacred legions (of Beelzebub), the Zographists (as they have recently been called) were tasked with pillaging the country and destroying anything they found, on the sacred orders of Zographos. Even the façade of a withdrawal only took place in part, because instead of returning whence they came as Epirotes, the Greek soldiers did not even leave the southern tip of Epirus.

Countless are the crimes and wrongdoings of the Zographist bands. All of southern Albania has been ravaged. The two beautiful provinces of Korça and Gjirokastra, including the districts of Bilisht, Kolonja, Leskovik, Përmet, Frashër, Skrapar, Opar, Tepelena and Kurvelesh have been devastated. As least 250 villages have been burned down, thousands of men, women and children have been massacred, and a hundred thousand people have been forced to flee their homes (most of them have now perished of starvation in Vlora).

In the Times of 10 May 1914, we find a Greek view of the crimes committed. Here even the Greeks recognise that “they burnt down villages on withdrawal and the rearguard, composed of Cretans, slaughtered everything so as to leave nothing to the Albanians.”

In face of the crimes of the Greek Government, it is obvious that our gendarmes and volunteers could not remain inactive. A line of over 150 kilometres was militarily defended; every square foot of land was fought over with Greek soldiers. Officially it was said that Zographos had only 10,000 to 16,000 men (see the Times of 9 April 1914). We had no more than about 3,000 gendarmes, and a few thousand hastily enrolled volunteers who were badly armed and badly equipped. We had no artillery at all at the start, and by the time we got some, the Epirus affair had already ended in a catastrophe.Despite their inferior numbers, our men fought bravely and put more than one "sacred legion" to flight. On 2 May, they were very close to Gjirokastra, two hours away at the convent of Cepo, which is four hours from Delvina. The Zographists fled before a handful of Albanians, hastily abandoned Delvina where they had their headquarters and retired to south of the border between the so-called Republic of Epirus and Greece proper, at the bridge of Arinista. But once they arrived there, they got reinforcements from Greek regular troops (10) and returned the next day, forcing our men to abandon their position.

On 7 May, a major Greek offensive was successfully repelled by our men at Nikolica and Arza (southeast of Korça), and the Greeks suffered great losses. Despite our sacrifices and sufferings, we read in the Times on 7 May a report from Athens dated 6 May that is effused with true Greek cynicism.

“Following recent combat activities, Epirot troops discovered the bodies of several Italian and Bulgarian officers.”

This was the eternal song of the Greek press and of those disseminating its articles. They always tried to see a foreign hand in Albanian efforts and shamelessly and unscrupulously denied that such activities could possibly be spontaneous. They were forever suspecting Austrian intrigues, or plots on the part of Italian or Bulgarian officers. And the Belgrade press was there as a choir, sometimes even playing the maestro itself.

Greek attacks continued day after day without pause, from all directions. What was apparent in this battle was the inferiority of the badly armed Albanians, with no artillery, in the face of an enemy that enjoyed all the advantages, in numbers and in arms. Greek resources were inexhaustible. How could it be that the army of His Majesty, King Constantine, was not involved? And were not Cretan adventurers and criminals ever ready to do patriotic deeds of murder and rape?Delusion reigned in Albania. The population hoped that the signatories of the Conference of London would intervene to force the Greeks to respect the decisions of the Great Powers and their commitments. Did not each of these Powers have a representative in Albania on the International Control Commission, and, at the Conference of the Ambassadors in London, was not Albania declared to be neutral and under the protection of the Powers?

The desperate population sent telegram after telegram to the Control Commission with its headquarters in Durrës and to the governments of the Powers. Some of these telegrams were worded in a very exacerbated tone. They resulted in a speech in the English parliament in April by the member Aubrey Herbert. The Greek ambassador in London denied everything. Lies and deception, are not these the characteristics of all good Greeks? In response, Aubrey Herbert published the detailed report that he had just received from Korça.

The delegates to the International Control Commission, when addressed individually, were well aware of the dishonest dealings of the Greeks and of the injustice and wrong done to Albania. But collectively, they were incapable of taking any initiative or action. Why? Because Venizelos had made a long tour of Europe and conducted extensive talks with the respective governments. There was also the issue of the Dodecanese that was related to that of southern Albania. And on top of this was the childish and ridiculous rivalry between the two Powers who were regarded as being directly interested in Albanian affairs: Italy and Austria.

In the meantime, the Albanian Government was obliged to embark on talks with the pseudo-government of Epirus and with its leader, the stigmatised Zographos. Initially, the late Colonel Thompson went to Corfu to listen to the demands of these so-called Epirots, but as he soon understood the farce being played by the Greeks, the talks went nowhere. At this time, there was a certain Varatassi in Durrës, a Kutzovlach from Konitsa, former governor of Corfu, who had been sent to Albania by the Greek Government as the future ambassador of Greece. He was a little fellow, of pathetic and rachitic appearance, who had the great advantage of pleasing Essad, of sinister memory, who was responsible for a good part of our woes. This Varatassi made proposals, wanted to act as an intermediary, and the International Control Commission set off for Corfu in full force to negotiate with the very same Zographos (8 May 1914). Greece appeared to be in a conciliatory mood. Zographos (who two weeks later was elected as a member of parliament for Attica), asked only for “a few concessions for the Greeks of Epirus, the recognition of their right to have Greek schools, and religious privileges for the Greek Church. But this was tantamount to recognising Greece’s right to interfere in Albanian internal affairs.

For whom was Greece, in the person of Zographos, demanding privileges? Who were the Greeks of Epirus? We have already stated, and can do so again here that “there is not a single Greek within the borders of Albania” as defined by the Powers at the conference in Florence. Those whom Greece called Greeks are none other than Albanian Orthodox Christians.

And it was more than anyone else these Orthodox who were terrified of Greek actions and who protested most vociferously. They were fed up with being called rum (i.e. Greeks) by the Turks who obstinately classified people by their religious affiliation without agreeing, or being able, to take into consideration their nationality and ethnic background. When these Orthodox heard about the talks between the International Control Commission and Zographos, Durrës was flooded with telegrams. We will provide some of them below.

But were Greece and Zographos at least being honest and sincere in their intentions? It is a waste of time to reply because everything we have said up to now is more than ample proof of the real intentions of our charming southern neighbours who were simply prevaricating in order to achieve their criminal enterprise.

More than once have they given proof of their treachery. More than once have they broken the ceasefire agreed upon at the talks in Corfu. And finally, without waiting for the dispositions (as they are called) to be finalized, they took advantage of domestic problems that we suffered due to the troubles in Durrës, crossed once again the provisional line set forth under the armistice, and attacked Korça in great numbers, while at the same time undertaking subtle attacks on all the other fronts.

Such is the Epirus question.

The result is that two of Albania’s most beautiful regions, Korça and Gjirokastra, have been devastated. Over two hundred and fifty villages have been razed, dozens of others have been pillaged and ravaged. Several thousand people have been killed in battle, or slaughtered in a most cowardly manner, including women and children. The material damage amounts to at least three hundred million francs, and a hundred thousand people are now homeless.

Here are some of the telegrams sent from Korça while the region was defending itself from Greek attacks and intrigues:

To His Majesty, the King of Albania,

We, the undersigned, in our capacities as representatives of the Albanian Orthodox community in Korça, have the honour to inform Your Majesty that we have just learnt from foreign newspapers that, because of our Orthodox churches and schools, Greece intends to intervene in Albanian internal affairs. If this news is indeed true, we, as citizens of Albania and subjects of Your Majesty, declare that we intend to demand that our government satisfy the needs we may have, and we will never allow a third party to intervene in issues affecting the political and moral independence of our nation, and the Orthodox community in particular. From the most humble and obedient servants of Your Majesty,

5 May 1914, (with the signatures of the vicar of the Orthodox Bishop and of the leading figures of this community).To Their Excellencies, the Ministers of Foreign Affairs in London, Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Rome and Petersburg.

We beg you, in the name of humanity, to cast an eye on the sorrowful fate of the Christian population of Korça and Kolonja. As Albanians, we are and wish forever to remain Albanians. However, under the ridiculous pretext of safeguarding our interests, but in actual fact to further their intrigues, the Greeks have made incursions into our districts, ravaged our country, and took our brothers with them by force when they withdrew. Their sole aim has been to destroy Albania and to make the civilized world believe in the existence of discord between the Christians and the Albanian Government. Greece forgets that the best thing it could do for us would be to leave us alone. We would ask you to use your influence to this end. Greece is causing us twofold suffering by ravaging our homes and by expatriating us by force, while threatening to kill us. On behalf of the Christian inhabitants of the Districts of Korça and Kolonja,

7 May 1914 [hereafter follow the signatures of the leaders of the Orthodox community of Korça and Kolonja].To His Majesty, the King of the Albanians,

We have just learned that several members of the Control Commission have returned from Corfu and are deliberating on the propositions made by Zographos, including privileges for southern Albania that would be extremely detrimental for the whole country and that would jeopardise its future. We also venture to inform Your Majesty that we, the inhabitants of the District of Korça who have always struggled and fought for the national cause, consider that our obligations to Your Majesty and to the nation require us to perish rather than to accept conditions leading to the break-up of the Albanian nation. We are fully convinced that the so-called demands will be rejected by Your Majesty and can assure you that we are able to defend the honour, prestige and integrity of the country with our own force, as long as we receive the cannons we have so long been waiting for.

22 May 1914 [hereafter follow the signatures]The above remarks are linked primarily to the activities of the Greeks in the town and surroundings of Korça. But the wrongdoings of our perfidious neighbours extend over the whole region of the two provinces of Korça and Gjirokastra (that the Greeks call Epirus), i.e. the coastline of the Adriatic to the banks of Lake Ohrid. Their fury has spared no one, neither the inhabitants, nor the homes, nor the animals, nor the harvest. In several villages the people were burned alive, for instance six men and three women were burned alive in Graca, southeast of Korça, on 5 April 1914 and four men and four women in Starja near Kolonja, southeast of Korça, on 30 April 1914.

The Greeks (soldiers and officers of the king of Greece) committed massacres elsewhere too, as in Kodra. We would need a whole volume to give details of all the crimes they committed. Here we will limit ourselves to reproducing two documents: the first is a report prepared by General De Veer, head of the Dutch mission to reorganize the gendarmerie in Albania; the second is a list of the 144 villages burned down by the Greeks, with the number of homes and inhabitants.

This list of villages is incomplete. We are reproducing it here as we found it in the Italian newspaper Corriere delle Puglie (of 14-15 December 1914) where it was printed after having been transmitted to the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and to the representatives of the five other Great Powers. As we have stated elsewhere, the total number of villages that suffered under the fury of the Neohellenists is at least 250, and even in this list, entire districts such as Gora, Devoll, the plain of Korça etc. are missing. Afraid that we might not be precise enough, we have preferred not to compile a list of our own, and have used this one, although it is far from perfect.

In the same issue of the said Italian newspaper, we also read about 48 tekkes (Bektashi monasteries) that were subjected to the holy terror of the Greeks.

In the wake of the Greek attacks and atrocities in southern Albania, almost all the population was forced to flee and take refuge in the regions of Berat and Vlora. The latter town was overflowing with refugees. Soon after Italy occupied this port and banned travel, both to the interior of the country and abroad by ship, famine began to ravage the population and over 30,000 of these unfortunate people who had escaped from the clutches of the Zographist assassins, perished in Vlora.

Thanks to the very Christian soldiers of Greece and their fervent acolytes from Crete, nothing but ruins remain of eleven once prosperous and flourishing districts (Gora, Devoll, Korça, Kolonja, Leskovik, Përmet, Frashër, Skrapar, Tepelena, Kurvelesh and Gjirokastra)

Report On the Massacre Committed in the Village Of Kodra on 29 April 1914

While in Tepelena on 12 May, the undersigned received the following telegram from the International Control Commission:

“The ICC, in agreement with the representative of Epirus, has decided to open an inquiry into the massacres of Hormova and Kodra in order to establish responsibility and find the perpetrators. It is understood that the commission of inquiry will be a mixed commission. The ICC thus asks you to send a Dutch officer to Hormova to work with the Epirot officer to whom the same instructions have been sent.

Corfu, 11 May 1914

The President

Mehdi Frashëri.

Pursuant to this telegram, I have designated as a member of this commission, Captain C. De Iongh in Tepelena, and have informed the commander of the Stepezi-Labova post, Dutch army major, H. De Waal in Stepezi, that an Epirot officer will report to the outpost as a member of the said commission. At the same time, I have given orders for this officer to be escorted to Tepelena immediately.

It must be noted that there have been false reports of massacres in Hormova and Kodra. The massacre in question here was committed only in Kodra, but most of the victims were inhabitants of the village of Hormova taken by force to Kodra by the komitadjis.

On 13 May, I received a dispatch from Major De Waal in which he informed me: “As of last night, the Minister of War of the Epirot Republic had not yet received orders from Zographos to appoint an Epirot officer to the commission of inquiry.” On the morning of 14 May, I was informed that the Epirot officer had not yet arrived.

In view of the importance of this event, I communicated this information immediately to the ICC, informing it that I would now begin the inquiry without the Epirot officer. I decided that the inquiry ought not to be further postponed because an impartial, just and in-depth investigation would be more and more difficult as the days passed, in view of the advanced state of decomposition of the bodies.

I was assisted in this inquiry, as members of the commission, by: the Major and medical expert, Dr. F. H. De Groot, Dutch Captain C. De Iongh, and Albanian Lieutenant Melek Bey Frashëri.

The Commission began it work that day, 15 May, by hearing as witnesses the governor of Tepelena and a few of the many refugees from Hormova and Kodra, mostly women who had lost a father, husband or son. The next day, 16 May, the commission visited the site of the slaughter.

Statements:

1. Fahri Bey Frashëri, Governor of Tepelena:

On 25 April, Tepelena was evacuated by the Greeks and on 26 April the gendarmes occupied the town. That same day, the komitadjis attacked the town unsuccessfully. According to two Christians, Kote Peçi and Dhame Kole Pestani, there were 300 Greek soldiers among the komitadjis, with their officers: Saghilari (machine-gun officer), Clemati, and a non-commissioned officer called Sthasthi.

Following the attack on that day, the komitadjis occupied Kodra, from where they fired on Tepelena with a cannon and machine-guns.

On 26 April, this Saghilari must have gone to Hormova with his Greek soldiers. There, he seized 40 inhabitants whom he took as his prisoners to Kodra. Several of those who escaped to Tepelena gave descriptions of this man, enabling him to be recognized.

On 28 April, a detachment was once again sent from Kodra to Hormova. This time, the detachment had a list with the names of the villagers, and they took 45 inhabitants back to Kodra with them.

Finally, on 29 April, for the third time, a detachment arrived in Hormova to seize all the men they could find. Apparently only 16 men, now in Tepelena, were able to escape.

That afternoon, the komitadjis left Kodra in the direction of Labova. Before their departure, they slaughtered all of their prisoners, among whom were five men from Salari, and five men from Luzat.

Terrifying cries were heard from the victims as far as Dragot, in the direction of Beçisht and in Luzat. Gun shots were also heard.

On the morning of 30 April, auxiliary troops from Luzat occupied Kodra and sent one of their men to Tepelena to inform the governor of the carnage that had taken place in Kodra.

On 1 May, the governor sent a lawyer from Vlora called Djevdet to the village to verify the truth of the news. He visited the village on 2 May, accompanied by Doctor Mussa and two gendarmes.

He went to several sites where large numbers of bodies had been buried, covered only with a thin layer of sand and, near the church, saw two unburied bodies, one of which had been decapitated.

2. Doctor Mussa:

He stated that near the church he saw two unburied bodies, one having been decapitated. Near them were human brains. To the east of the village, he came across an oblong ditch of about 20 metres in length covered in sand that was drenched in blood. He also visited the posts requested by the governor.

3. A woman called Bezai from Hormova:

This woman had one son, Bek Seferi, whom she found decapitated near the church. The body had not been buried. She saw the corpses of four of her cousins in the big ditch behind the church. The heads of some of them were so mutilated that she could only recognised them by their clothes.

She believes that the village lost over 200 inhabitants. They were seized in three groups by the inhabitants of Lekli and Labova, supported by Greek soldiers under the command of an officer. On the first occasion, they also took about forty sheep.

4. The statements of 16 other women are the same:

They declared in the same manner how the men of Hormova were taken to Kodra in groups. They also state that the komitadjis stole everything they owned: money, sheep, clothing, furniture, etc.

5. Ramo Ibrahimi:

This man was with his son and his sheep in Labova. When the komitadjis arrived, he hid and later fled to Tepelena. He does not know where his son was taken when he was captured with the sheep by the komitadjis. He also lost his brother and the latter’s son.

6. Two other men:

Two other men from Hormova, who went into hiding when the Greek officer arrived in the village with his men, also gave statements. They fled to Tepelena when the officer and soldiers departed.

7. Tepelena hospital:

At Tepelena hospital, Dr. De Groot cared for a little ten-year-old boy called Resul who had a large wound to his chest. He was in the mountains south of Hormova guarding his sheep when he was caught by surprise by the komitadjis who took him and his sheep in the direction of Gjirokastra. He was able to escape en route and fled up into the mountains, where he met seven other boys. Together, however, they were surrounded by the komitadjis who fired at them. The result was that Resul was seriously wounded. Nonetheless, he managed to get to Tepelena.

The Visit of General De Veer to Kodra

On 14 May, a few days after my arrival in Tepelena, I (De Veer) visited Kodra in the company of the physician, Dr. De Groot. The air in the village reeked of the bodies of cows and sheep, all in an advanced state of decomposition.

Site of the massacre of Kodra,

29 April 1914 (Photo: Carel De Iongh).South of the village there is a little church which had doubtlessly been used as a jail. The walls and floor in it were tainted with blood. There were blood-drenched clothes and fezzes everywhere. The doctor pointed out the remains of human brains. A blood-stained rope was hanging from the ceiling where the altar had once been.

The little wooden door of the church was riddled with holes, and the cartridges in front of the door made it clear to visitors how the holes got there. By removing a few tiles from above the door, one could see two oblong openings, both filled with cartridges.

Behind the church there was a large pit and it was not difficult to recognise the shapes of human bodies under the thin layer of sand. Lower down, in front of the church, I saw a few bodies in a little pit.

To the east of the village, there is a small house surrounded by trees. Near one of the trees, I could clearly see a pit of about 15 metres in length where the earth was drenched with blood, and under the tree there were still pools of blood. At a distance of 50 to 100 metres from this tree, we visited three large and one small pit. In one of the large pits, we saw the corpse of a headless woman.

The bodies had been hastily buried. In order to prevent the spread of disease, Dr. De Groot ordered the bodies to be removed from one of the pits so that it could be dug deeper and the bodies reburied properly. A horde of gypsies began this dismal undertaking on 16 May.

The same day, the commission visited Kodra. It inspected the two pits (a and b) that had been emptied. The one behind the church (a) contained 34 bodies, several of which with fractured skulls. Nineteen bodies were found in the second opened pit (b), several of which with fractured skulls.

As the physician decided that it was not necessary to open the other pits since they were deep enough, the commission completed its work. One of the pits (c) had earlier been used to make cement. It was 4-5 metres deep. Being filled for the most part with human remains, it must have contained about 100 corpses.

The other pits contain 34, 2, 19, 20 and 20 bodies respectively. A total of 195.

With this report, I have the honour of submitting to the Commission a list of names of the people presumably killed in Kodra (annexed to his report is a list of 217 names).Tepelena, 19 May 1914

Lieutenant-General De Veer

Physician, Major F. De Groot

Captain De Iongh

Lieutenant Melek Frashëri

List of the Villages Destroyed by Fire

Village Ftera Lekdush Progonat Nivica Vergo Zhulat Kuç Borsh Palavli Kalasa Kallarat Konguc Kolonja (Laberia) Picar Sasaj Golem Gusmar Tatzat Bolena Reçin Kopaçe Çoraj Shtepez Kardhiq Gjirokastra Plesat Prongji Dorza Fushëbardhë Tepelena Luzat Dukaj Dragot Dams Mezhgoran Salari Merthinje Potgoran Kiçok Arza Toskamartalloz Shelq Turan Marican Benja Kashisht Bença Hormova Bubes Beçisht Veliqjot Melçan Vasjar Pavar Zavalan Klisura Gerpska Vinokash Benjeza Përmet Ogren Virtenig Markat Vilusha Qjafa Manubas Prishta Panarit Bistrovica Alipostevan Rodina Bagri Brezhdan Kurtes Frashër Rriban Varibope Miraslavica Çepan Malind Seropol Delvina Navarica Sevran Topojan Tolari Kajca Zhepova Memalian Mazhan Pale Rodiq Fratar Qeshibesh Koprencka Backa Gjergjova Panarit Floke Trebicka Selenica Taç i poshtëm Taç i sipërm Leskovec Muzhaka Qjafzez Kreshova Malinat ?? Kakosh Muzencka Kalltan ?? Qinam Qyteza Raja Bejan Gjonç Mesar Skorovod Lencka Barmash Qesaraka Herseka Selenica Pesar Lubonja Starja Gostivishti Luaras Pacomit Shalës Kocke Leskovik Peshtan Radan Radat Novosela Bejkova Kagjinas Hoseçka Verpska Konispol Leshnja Poda Zhepova Korone

We can guarantee the authenticity of this quote which was heard by several witnesses. The bickering of the Greek government provoked the disgust and impatience of Mr Asquith, the Prime Minister of Great Britain. For us, Epirus is the south of Albania, down to the Gulf of Arta. For the Greeks, it is only the part formed by the provinces of Korça and Gjirokastra. The following two paragraphs are taken from the newspaper Koha, French and English edition. No, 1, issued in Korça on 3/16 March 1914. The second and last issue of this newspaper appeared on 15/28 May. cf. Brailsford: Macedonia, its Races and their Future, London 1905, that contains a description of the Bishop of Kastoria and the religious terrorism of the Greeks. There is general confusion on the subject among all Greeks. The former Greek consul general in Salonica, who is now plenipotentiary minister in Rome, used the same terminology in an official speech. Most recently, in January 1915, the Venizelos Government claimed in all sincerity that there were 1800 Greeks in Durrës, while he was actually referring to Orthodox Christians. The Athens Messenger of 9 January (new style) 1915: “The Greek community of Durazzo, according to official statistics, consists of no more than 2,000 souls.”!! In April 1914 there were three young foreigners in Korça: Count Pimodan (French), Prince Stourdza (Romanian) and Mr H. Sherwood Spencer (American). Although they were simply travelling through as interested tourists, these three gentlemen found themselves in the midst of battle between the Albanians and the so-called Epirotes, in Kolonia, southwest of Korça. They saw with their own eyes that the men called Epirotes were really none other than Greek soldiers and officers, or Cretan scoundrels. We wish to recall here that in the whole Epirus affair, there was only Zographos and his colleague Spiro Milo who were actually Epirotes, i.e. Albanians. The former was born of a father from Gjirokastra and the latter was born in Himara. Both were very young when they joined Greek service and, like all traitors, they showed servile devotion to the Greek cause. We have chosen to quote the newspaper Times because of its scandalously Grecophile character than for any other reason. All or almost all the Greek officers who proclaimed that they were Zographists and Epirots are now in the Greek army and have been promoted. [from: Lumo Skendo (Mid’hat bey Frashëri), L’Affaire de l’Epire: le martyre d’un peuple (Sofia: L’Indépendance Albanaise, 1915). 48 pp. Translated from the French by Robert Elsie.]

TOP