| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1916

Konstantin Jireček:

Scutari and the Surrounding Region in the Middle AgesCzech historian Konstantin Jireček (1854-1918) was professor of Slavic studies and history at the University of Vienna. Although primarily a Bulgaria-expert, he published many lucid articles on Albanian history, including this inventory of the major early settlements of the Shkodra (Scutari) region in the Middle Ages.

Konstantin Jireček (1854-1918).One of the largest lakes in the Balkan Peninsula is Lake Scutari [Shkodra]. The Romans called it lacus Labeatis or palus Labeatis, from the Illyrian tribe Labeates. In the book of Presbyter Diocleas it is called Balta, as are the little marshy lakes along the coast of Dulcigno [Ulqin/Ulcinj], Durazzo [Durrës] and Valona [Vlora] at the end the Middle Ages. The scholars among the earlier Serbs called it the Lake of Diocletian (Dioklitijsko jezero). At the Venetian printing press of Božidar Vuković of Podgorica in 1520 there was a collaborator called the Monk Pachomije who was "from the islands in the lake of Diocletian" (cf. Novaković in Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini 45, p. 135).

The lake is 42 kilometres long, 14 kilometres wide and about 362 square kilometres in size. On the western bank of the lake are steep cliffs, with islands on which there are ruins of old monasteries and castles. The eastern bank of the lake is flat and marshy. Half way down it, there is an inlet, one to two kilometres in width, that extends for some twelve kilometres eastwards. The outer part of it is known as the lake of Kastrati (Alb. Ljekeni Kastrati) [Liqeni i Kastratit], and the inner part as the lake of Hoti (Alb. Ljekeni Hotit) [Liqeni i Hotit], after two Albanian tribes that live in the neighbourhood. The surface of the lake is no more than six metres above sea level. For this reason, the climate on its banks is just as warm as that on the coast, with Mediterranean fruit and olives, etc. The lake is nourished primarily from the northern end, where we find the river Morača with its tributaries the Zeta, the Ribnica and the Cijevnja (in the fourteenth-century chrysobulls preserved at the monasteries of Banjska and Dečani, it was called Cjemva; Alb. Cem). To the west of this is the large river Crnojevića Rijeka and the smaller Crmnica. From the east comes the river Rioli [Rjoll], fiume clamado Rivola 1426 (cf. Ljubić 9, p. 15), with its old Latin name (rivulus).

One of the largest lakes in the Balkan Peninsula is Lake Scutari [Shkodra]. The Romans called it lacus Labeatis or palus Labeatis, from the Illyrian tribe Labeates. In the book of Presbyter Diocleas it is called Balta, as are the little marshy lakes along the coast of Dulcigno [Ulqin/Ulcinj], Durazzo [Durrës] and Valona [Vlora] at the end the Middle Ages. The scholars among the earlier Serbs called it the Lake of Diocletian (Dioklitijsko jezero). At the Venetian printing press of Božidar Vuković of Podgorica in 1520 there was a collaborator called the Monk Pachomije who was "from the islands in the lake of Diocletian" (cf. Novaković in Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini 45, p. 135).

The lake is 42 kilometres long, 14 kilometres wide and about 362 square kilometres in size. On the western bank of the lake are steep cliffs, with islands on which there are ruins of old monasteries and castles. The eastern bank of the lake is flat and marshy. Half way down it, there is an inlet, one to two kilometres in width, that extends for some twelve kilometres eastwards. The outer part of it is known as the lake of Kastrati (Alb. Ljekeni Kastrati) [Liqeni i Kastratit], and the inner part as the lake of Hoti (Alb. Ljekeni Hotit) [Liqeni i Hotit], after two Albanian tribes that live in the neighbourhood. The surface of the lake is no more than six metres above sea level. For this reason, the climate on its banks is just as warm as that on the coast, with Mediterranean fruit and olives, etc. The lake is nourished primarily from the northern end, where we find the river Morača with its tributaries the Zeta, the Ribnica and the Cijevnja (in the fourteenth-century chrysobulls preserved at the monasteries of Banjska and Dečani, it was called Cjemva; Alb. Cem). To the west of this is the large river Crnojevića Rijeka and the smaller Crmnica. From the east comes the river Rioli [Rjoll], fiume clamado Rivola 1426 (cf. Ljubić 9, p. 15), with its old Latin name (rivulus).

Lake Scutari is shallow, only 2-7 metres deep according to Cvijić. Towards the western bank there are a few deeper sections of 44 metres. Fishing was always very important, in particular, for bleak (Alburnus scoranza), Serbian ukjleva, Italian scoranza. In Mediaeval Latin documents this fish appears as saracha. The level of the lake has often changed. When the Drin broke its way through into the Bojana [Buna], the outflow was blocked in the lake and the water level rose. They say that it has been on the rise for the last forty years or more, ever since the two great rivers merged again. When the Bojana had no contact with the Drin, the water level subsided.

The mountainous west coast of the lake was of less significance in the past. There were two župas (provinces) here. One was Crmnica which was called Cermenica by Presbyter Diocleas. In fourteenth and fifteenth century documents, it appears as Crvnica (probably from Old Slavonic črmьnь meaning “red”). In the Nemanja and Balšić periods, most of the villages of Crmnica were owned by the monastery of Saint Nicholas on the island of Vranjina. South of Crmnica was the župa of Krajina (Alb. Kraja), formerly a border region separating the Serbs from the Greeks when the latter possessed Scutari. The name occurs in Diocleas as Craini, as well as in other historical documents. A Serbian prince, the holy Vladimir, held court (curia) at the Church of St Mary's in Krajina. He was buried there after the last tsar of Ohrid, John Vladislav, had him murdered on the island in Lake Prespa around 1016. As far as can be ascertained, the troops of Michael I, the Despot of Epirus, stole his remains from the church when they took the town of Scutari from the Serbs for a short time around 1215, and took the saint to Durazzo. Since the fourteenth century, his remains have been buried at the monastery of Saint John Vladimir near Elbasan (cf. Novaković, Prvi osnovi slovenske književnosti medju balkanskim slovenime, Belgrade 1893, p. 182 sq.). At the time of the Balšić dynasty, the old monastery of Krajina was referred to as the Virgin Mary of Krajina (Prečista Krajinska) (cf. Dučić in: Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini 27, p. 190). According to Jastebov and Rovinskij, the ruins of the monastery are situated 3½ hours from Scutari at the foot of Mount Taraboš [Tarabosh], in an area now inhabited by Muslim Albanians. Here in the village of Ostroš, Ippen came across the ruins of a great church with a rectangular tower above the entrance (cf. Wissenschaftliche Mitteilungen aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina, 8, p. 137 sq. with ill.). Below Ostroš lies the virtually abandoned village of Śtitar at the lakeside. Between Śtitar and Scutari, on the lake, is the village of Śkja with a little church containing vague traces of mural paintings (Photo by Ippen in: Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini, 1900, p. 517, and in: Wissenschaftliche Mitteilungen aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina, 10, p. 27).

There were five small monasteries on the islands. Everything that was known about them was assembled by the late Archimandrite Hilarion Ruvarac in the periodical Prosvjeta published in Cetinje in 1894 (Year II). The largest of the monasteries was that of Saint Nicholas on the island of Vranjina, across from the mouth of the Morača. On this island there are two rocky hills, 330 metres high, that offer an excellent view of the lake and its surroundings. This monastery received many rich endowments from the leaders of the Nemanja and Balšić dynasties and later from Skanderbeg Crnojević, the Sandjak of Crna Gora, in 1527. It was linked for some time to the Serbian monastery of Saint Michael and Saint Gabriel in Jerusalem, on which the Emperor Stephen Dushan bestowed it. It only declined and was abandoned recently when, after 1843, the Turks constructed a fort and artillery positions against the Montenegrins on the island. It was restored in 1886. On the neighbouring island of Kom, also known as Odrinska Gora, there was a monastery dedicated to the Virgin Mary. In its walls there was the grave, with an inscription, of Lješ Gjurašević (Crnojević), a commander of the Despot Stephen. Next to this island is Starčeva Gorica which once had a monastery known for its old manuscripts. It is now completely abandoned. Božidar Vuković who printed Serbian ecclesiastical books in Venice died here († 1540, cf. Godišnjica, Annual of the N. Ćupić Fund, 9, p. 205). On the island of Beška Gorica there were two churches, one to Saint George and the other to the Virgin Mary. In the ruins of the latter there was the grave, with an inscription, of Helena, the daughter of the Serbian Prince Lazar, who was the wife of George Stracimirović Balšić and later the wife of the Bosnian Grand Voivode Sandalj († 1442). On the island of Moračnik there was a monastery dedicated to the Virgin Mary, founded in 1417 by the last of the Balšić rulers, Balša (III) Gjurgjević.

Of greater significance is the mostly flat eastern bank of Lake Scutari because it was here that the road from Scutari to Nikšići and the valley of the Narenta led, well known since Roman times. Five kilometres north of the present town of Podgorica, on a fertile plain along the middle section of the Morača River, where it is joined by the Zeta, are the ruins of Doclea, the largest Roman settlement in the region. This was originally the site of a fortress of the Illyrian Docleates or Docleatae tribe, who lived in what are now the mountains of Montenegro. In the village of Vilusi near Grahovo, in the ruins of the Roman castle of Salthua, Latin inscriptions were recently found stemming from the chiefs of the Docleates (cf. N. Vujić in Vjesnik of the Archaeological Society of Zagreb N.S., 8, 1905, p. 172). Doclea was accorded the status of a Roman municipium by the Emperor Vespasian or his sons. There are two works on these ruins that include both a pagan temple and the remains of an early Christian church. One was written by the English scholars William Anderson, Francis Haverfield, Joseph Milne and John Munro: On the Roman Town of Doclea in Montenegro, in Archaeologia, vol. 55 (Westminster 1895). The other one was a treatise by the Italian archaeologist Piero Sticotti of Trieste in collaboration with two Dalmatians, Professor Luka Jelić and the architect Iveković, Die Römische Stadt Doclea in Montenegro [The Roman Town of Doclea in Montenegro], with one table and 148 illustrations in the text (Vienna 1913), published by the archaeological section of the Balkan Commission of the Austrian Imperial Academy, vol. VI. The town was abandoned during the unrest of the seventh century but its name was never forgotten. A small settlement seems to have survived here. It was the see of the bishop Διοκλείας under the Greek metropolitan of Durazzo and is referred to in the history of the Emperor Manuel Comnenos of Kinnamos as the fabled city of Διοκλεία. Influenced by the legends of the Emperor Diocletian, the name Doclea became Dioclia. Božidar Vuković wrote in 1520 that he stemmed from Podgorica "near the town called Dioklitia which the Emperor Diocletian once built and to which he gave his name." Even today, the Montenegrins call the ruins Duke or Dukla and tell various tales of Tsar Dukljan. In the Middle Ages, in the works of the Emperor Constantine Pophyrogenetus and the Commander Cecaumenus, the whole region was called Dioclia or Διοκλεία after the town, in Serbian Dioklija or Dioklitija, the land of the Serbian tribe of the Dioklitianes. One of the Muslim descendants of the last dynasty to rule over the mountains of Montenegro, Skanderbeg Crnojević, described himself in 1523 as "Sandjak of Crna Gora and Lord of the whole country of Dioklitija" (vsoj dioklitijanskoj zemlji gospodin). However, from the twelfth century onwards, the name was gradually replaced by Zeta (Latin Zenta, Genta), named after the river Zeta. Upper Zeta was situated in the Njeguši mountains above Cattaro stretching down to the eastern side of Lake Scutari. Lower Zeta was the coastal area from the tribal lands of the Paštrovići near Budua [Budva] to the monastery of Saint Sergius [Shirq] on the Bojana.

The fortress of Medun in the tribal region of the Kući is older than Doclea. It is the castle of Meteon or Medeon in the tribal region of the Labeates where in 168 B.C., according the Polybius and Livy, the Roman legate Perperna captured the wife of the Illyrian King Genthius, Queen Etleva, and her sons Scerdilaedus and Pleuratus. At the time of the Serbian despot, George Branković, it was referred to as Medonum or Modon. A Venetian author describes it as being only one tower (una torre) and a small castle where there was hardly enough room for the castellan and his guards (cf. Ljubić, 10, p. 151). In 1456, Medun was still commanded by Miloš, a voivode of the despot, but soon thereafter, the Turks took up residence here. Stephen Crnojević of Montenegro wanted to take this "key to the two Zetas, at the head of Upper Zeta" from the Turks (Medonum oppidum in capite superioris Xente situm, ambarum Xentarum clevem). To this end he received canons from the Venetians, but his attempt failed. Mariano Bolizza, a patrician from Cattaro, wrote in 1614 that Medun was a badly guarded site and more or less in ruins (piazza mal guardata e quasi destrutta), with 200 inhabitants and a Turkish Aga or dizdar as its commander (cf. Ljubić, Starine, 12, p. 182). The significance of this site in modern Montenegrin history is well known. At any rate, Medun is one of the few fortresses of Europe whose history goes back twenty centuries.

The successor to Doclea was Ribnica, which in the twelfth century was the birthplace of the Serbian grand župan [prince] Nemanja. Nowadays, the word Ribnica refers to the river that flows through Podgorica and there is no doubt that the ancient settlement of Ribnica was on the site of this town. The word Podgorica first appears in the oldest notary register of the court archives of Cattaro where leather workers and tinkers are referred to as living there in 1330. The word is connected to the name of the župan of the period; on the eastern side of the lake was the Gorska župa (mountain district) of Presbyter Diocleas mentioned in the Charter of Žiča (around 1220); the region of Podgora ("under the mountain") was subsequently mentioned in the Prizren Charter of Tsar Stephen (around 1348) and the Venetian cadastral register of Scutari of 1416. In 1448, the Serbian nobleman Altoman, who was a voivode of the Despot George, was still living in Podgorica. The settlement soon fell to the Venetians and a few years later to the Turks who held it until 1877.

Tuzi across from Podgorica is an old settlement. It is referred to in the chrysobull of the monastery of Dečani (1330) as the katun (herding community) of the tribal leader Lješ Tuz. The Venetian cadastral register of 1416 refers to it as the large village of Tuzi with 150 houses that were to provide 500 fighters, some as cavalrymen and others as infantrymen (cf. Makušev, Istoričeskija razyskanija o Slavjanakh v Albanii v srednie veka, Warsaw 1871, p. 127). There are ruins at the edge of the mountain called Samobor. To the south of the town live Albanian tribes: the Hoti, mentioned since 1330, who were a large tribe in the fifteenth century and according to Bolizza (1614) had 212 houses and 600 armed men; the Škreli [Shkreli], mentioned in 1416, who according to Bolizza had 30 houses; and the Kastrati, who are referred to by Bolizza as having 50 houses.

Three hours from Scutari, near the Rioli River, lies the hill Maja Balezit [Maja e Balëzit] that offers a good view. On it are the ruins of Balezo [Balëz]. According to Jastrebov, they cover a surface half the size of the fortress of Scutari. The rest of the area, including a large and a small church, is covered in bushy vegetation (cf. Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini, 48, p. 382). According to Ippen, the peak of the mountain has a circumference of 1,000 steps. Among the bushes, one can see the remains of the city walls and a church, but the ruins are not as extensive as those of Svač [Shas], Sarda [Shurdhah] or Drivasto [Drisht] (cf. Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini, 1900, p. 512, and Wissenschaftliche Mitteilungen aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina 10, p. 6-9, with ill.). This was the site of the small town known variously as Baleç, Balezo (or Baleço), Ballegio, Ballesio, Baleçio of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, with a bishop (Balaçensis episcopus), who was subordinate to the Archbishop of Antivari [Bar]. In 1356, the bishop complained that he had no income because his diocese was full of schismatics (cf. Theiner, Vetera monumenta slavorum meridionalium historiam, Rome 1863, 1, p. 236).

The archival records of Ragusa [Dubrovnik] mention handicraftsmen from this town: carpenters (marangoni) and shoemakers (cerdoni). According to the cadastral register of 1416, the cità da Balezo had 25 houses (cf. Starine, 14, p. 38). Soon thereafter it was abandoned. Ivan Crnojević, Prince of Montenegro, reported to the Venetians in 1474 that the Turks intended to fortify Balezo once again (cf. Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini 15, p. 173). Barletius refers to the site as a ruin twelve Roman miles from Scutari and five miles from Drivasto.

Situated near Balezo is the Muslim village of Koplik, called Cupelnich by Presbyter Diocleas, Kupêlnik belonging to the monastery of the Archangels near Prizren, founded by the Emperor Stephen Dušan around 1348, and Copenico in the Venetian cadastral register of 1416. According to this register, it was the home of many Serbian clergymen: Jura des Protopope, Pop Andrea, Pop Nikašin, Pop Miliza, Pop Stanko, Pop Bogdan, Pop Radoslav Tribov and Pop Radovan. Most of the inhabitants had Serbian names: Ivan Sudija (the judge), or Sudić, Pribac Budimir, Ivan Budimir, Bogdan Nalješko, Novak Milić, Ratko Vlahinja, Bratoslav Kovač (the blacksmith), Ostoja, Novak Tribov, Bogdan Bogšić, Andreja Kraguj (the hawk), Ratko Bogoje, Dimitr Bogić, Dabiživ Široko etc. The headman of the village (villa) was Thomas, scribe of the chancery of Scutari for correspondence in Slavic (scrivan de la corte in schiavo) (cf. Starine, 14, 34).

Scutari is situated on a plain a mere 18 metres above sea level, above which rises an isolated rocky hill of elliptic form, 135 metres high, offering a splendid view of the lake and the whole region, in particular the high mountains of Montenegro and Albania. Only the sea cannot be seen from here, as it is blocked by a ridge of low hills. Since ancient times there has always been a fortress on this hill.

The Bojana River flows out of the lake near Scutari. Farther to the east, one of the largest rivers of the Balkan Peninsula makes its way out of the mountains. It was called Drilon by the Greeks, Drino (gen. -onis) or Drinius by the Romans, Drinus in mediaeval Latin or with the Romanic article Ludrin, Lodrino, Oldrino, Uldrinum, Drin in Albanian and Drim in mediaeval and modern Serbian. The root is der- (Iranian derena, darna 'gap, ravine,' Greek δείρω, Slavic derem, drati), as in the name of the river Drina between Bosnia and Serbia. Tomaschek noted that the names of both rivers had the same meaning. This river channels the water of a large region into the Adriatic Sea. The Black Drin begins its course in Lake Ohrid; the White Drin flows down from the high mountains around Peć [Peja], Turkish Ipek. Its estuary is situated near the town of Alessio [Lezha], but in addition to this estuary, the Drin has often made its way through a sidearm into the Bojana, near Scutari. This happened in Roman times, too. Livy writes that the town of Scutari was surrounded by two rivers: from the east by the Clausala (Drinassi or Kjiri [Kir]) and from the west by the Barbanna (Bojana). The two rivers united and flowed into the Oriundus flumen (as recorded in the manuscript, but this is probably a mistake for Drinius), which came ex monte Scardo (from the Šar Planina [Sharr Mountains]) and flowed into the Adriatic. Pliny offers a clearer description, saying that Scodra was situated on the river Dirino 18 Roman miles from the sea. The two rivers were linked in the thirteenth-fifteenth centuries, too, when the Bojana was often called the flumen Drini. Saint Nicholas at the mouth of the Bojana was called San Nicolo de Drino or de Oldrino (in the archival books of Ragusa). Saint Sergius [Shirq] on the Bojana was known as portus Sancti Sergii de Drino in 1282, de Oldrino in 1349, and as Sanctus Sergius Lodrini in 1391. But at the end of the fifteenth century, the Venetian geographer Domenico Negri wrote that the Drin had changed its course and that near Scutari one could see dry riverbed (pristino mutato cursu, quod manifeste apparet, sub ipso namque oppido ad montis radices alveus repletus cernitur et magni pontis fundamenta, p. 105). The old riverbed was marked on the map of the Venetian Coronelli in 1688. In 1577, an anonymous Venetian traveller wrote that the banks of the Bojana were green because the river never rose (le ripe del fiume, non solendo egli crescere, sono verdi, cf. Starine, 10, p. 251). Ami Boué notes simply that the waters of the Bojana and the Drin were once united: "la plaine de Scutari, qui, en son niveau bas, servait probablement une fois à réunir les eaux du Drin à celles du lac et de la Bojana" (cf. Recueil d'itinéraires, 1, p. 334). The Drin most recently broke through in a northwest direction in the winter of 1858-1859. The weak dams that had been constructed there were broken down and for two winters on end, the river devastated the whole plain of Scutari with dreadful flooding, until a new riverbed was formed in the third winter. The inhabitants say that two-thirds of the water flows through the new bed and only one-third down the old Drin to Alessio (cf. Hahn, Reise durch die Gebiete des Drin und Vardar, im Auftrage der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften unternommen im Jahre 1863. Denkschriften der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien. Phil-hist. Cl., Vol. 16, p. 34, 36).

The Drin and Kir rivers near Shkodra

(Photo: Robert Elsie, March 2008).

Scutari has not changed its name in two thousand years. The Romans called the town Scodra, as did the Greeks. Only the Byzantines made a slight change when they pluralized the name as Σκόδραι. Presbyter Diocleas wrote Scodaris, and the adjective Scodrinensis. Since 1287 one also encounters the form Scutarum (adjective Scutarensis). The old Serbian form was Skьdьr, with two weak vowels. This form can still be heard in Montenegro. The modern form, Skadar, has been around since the end of the fourteenth century. In Italian, the town is known as Scutari, in Albanian as Skodra or Škodra [Shkodra], in Turkish as Skenderié or Iskenderié. Hahn believed that the word derived from kodra “hill.”

The kings of ancient Illyria resided in Scutari. There are coins bearing the inscription Σκοδρεινῶν and the picture of a helmet. The oldest description of the town, from Livy's history of the war against the Illyrian King Genthius (XLIV, chapter 31) dates from 168 B.C. Scodra was the best defended (arx munitissima) and hardest to get to (difficilis aditu) of all the fortresses of the Labeates tribe. It was a naturally fortified position (munitum situ naturali oppidum), surrounded by walls with towers over the gates (portarumque turres). When the Roman praetor Lucius Anicius appeared before it, King Genthius, of whom there are also coins with Greek inscriptions, went on the attack, but was repulsed and had to withdraw into the fortress. He negotiated a ceasefire and fled onto a ship waiting at sea. When he realised that his path of flight was blocked, he surrendered to the Roman commander who took the last king of Illyria to Rome with him. Scodra became a Roman city, one of the major settlements in the south of the province of Dalmatia, where the Emperor Diocletian would later set up a new province of Praevalis. Christianity was early to spread here and the town has had bishops since the fourth century. The history of this diocese stretches from Roman times right to the present. When the Roman Empire was divided into a western Rome and an eastern Rome, Scodra and all of Praevalis remained with the eastern half, under Constantinople. When the immigration of the Slavs changed the situation of these countries in the seventh century, the Byzantines kept control of Scutari, Drivasto, Alessio, Dulcigno and Antivari as part of the "theme" of Dyrrhachion [Durrës]. Although the inhabitants of these towns were mostly descendents of the ancient Romans, we find in old catalogues that their bishops were dependent upon the Greek bishop of Durazzo. The Serbs seized Scutari in the eleventh century. At that time, they were supporting the Latin Church against the Greek, and as such, the bishops of these towns were subordinated to the new Latin archbishop of Antivari. When the southern French crusaders passed through Scutari in 1096, they came upon the Serbian King Bodin, who welcomed the Provençal leaders warmly. The emperors of the Comnena dynasty, in particular the Emperor Manuel, got this coastal region under Byzantine control once again. With the death of Manuel in 1180 and the fall of the empire in Constantinople, Scutari and all the neighbouring towns were conquered by the Serbian grand župan Stephen Nemanja. It was the first Depot of Epirus, Michael I, who undertook a last attempt to return the region to Greek rule, around the year 1215. He took Scutari from the son of Nemanja, the grand župan Stephen (who later became the "first crowned" king), but when the Epirotic despot suddenly perished, the town was quickly retaken by the Serbs and remained in their possession throughout the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

In the biography of Stephen the First Crowned (pre-1215), the fortress of Scutari is called Rosaf. Marinus Barletius (ca. 1480) refers to it under the name Rosapha. It is also mentioned by a number of writers in the nineteenth century. The fortress derives its name from a legend, a curious but not uncommon phenomenon. It comes from the now abandoned city of Rusafa, which is mentioned in the legend of the Roman soldiers, Sergius and Bacchus. Situated in eastern Syria in the deserts of the Euphrates not far from ancient Palmyra, its walls and buildings are well preserved. Below Scutari there was a famous monastery on the Bojana River that was dedicated to these two saints and the people ascribed the town from which the Syrian martyrs stemmed to the surroundings of the monastery (cf. Hilarion Ruvarac, Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini 49, p. 39-41, and my article Das christliche Element in der topographischen Nomenclatur der Balkanländer, in: Sitzungsberichte der philosophischen-historischen Classe der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna, 136. 11 (1897), p. 48-54).

Under the Nemanja dynasty, Zeta and Scutari were the territory of the successor to the Serbian throne. After the fall of the Serbian empire, the Balšić dynasty began to rule here, from about 1360. Later, in 1392, the Turks took George Stracimirović Balšić prisoner and did not release him until he agreed to surrender Scutari to them. The Turkish commander Shahin ruled over Scutari and Saint Sergius [Shirq] from 1393-1395. George managed to drive the Turks out two years later, but in April 1396, he was obliged to abandon Scutari, Drivasto, Dagno [Deja] and Saint Sergius to Venice. The Venetians held onto Scutari for 83 years, from 1396 to 1479. The Republic of San Marco was represented here by a capitaneus et comes. The Serbs endeavoured in vain to retake the town. They besieged Scutari twice, once at the end of 1421 under the Depot Stephen Lazarević, and a second time in 1422 under the Despot and then under his commander Mazarak, until Niccolò Cappello, who stood ready with the Venetian fleet near Saint Sergius, repelled the Serbs in a decisive assault on Dagno one night in December (cf. Jorga, Notes et extraits pour servir à l'histoire des Croisades au XVe siècle, 1 p. 329, footnote 4).

After the fall of the Christian realms of Serbia, Bosnia and Albania, the Turks advanced through this region once again. In 1474, under Sultan Mehmed II, the Beylerbey of Roumelia, Suliman, besieged Scutari, but the town was courageously defended by Antonio Loredano and his 2,500 soldiers, with the help of Venetian ships waiting in the Bojana and at sea, and with the support of the Crnojevići of Montenegro and the Albanian highlanders. The second siege in 1478, recorded by the priest Marinus Barletius in minute Latin script, was led by Sultan Mehmed II himself. The Venetians defended the town heroically but were forced to evacuate it after a peace agreement in 1479. Of their 1600 soldiers, only 450 remained. The population, under their leader Florio Jonima, departed and settled in Venice, Ravenna and Treviso. From that time until 1913, a period of 434 years, Scutari has been under Turkish rule.

The centre of old Scutari was the fortress (castrum), which was only accessible from one side. According to the description of Ippen, it is surrounded by double walls. Throughout the fortifications, one finds remnants of Venetian architecture. The old buildings were destroyed in a gun powder explosion in the nineteenth century. To enter, one passes through three gates, each in a tower, followed by three courtyards. In the central courtyard there is a mosque with remnants of a Gothic vaulted ceiling and sculptures (cf. Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini 1902, p. 181, and Wissenschaftliche Mitteilungen aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina, 10, p. 47 sq.). This was no doubt once the Cathedral of Saint Stephen (ecclesia cathedralis Sancti Stephani de Scutaro), that became famous in 1346 for its miracles (cf. Theiner, Vetera monumenta slavorum meridionalium historiam, Rome 1863, 1, p. 219). The Emperor Stephen Dushan gave the "millrace (jaz) of Saint Stephen" in Scutari to the Monastery of the Archangels near Prizren (cf. Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini 15, p. 288) when he seized the Catholic diocese during a conflict with the Latin Christians. The Turks transformed the old cathedral into a mosque. An old, broken-down organ (organo disfatto) still stood in the building as a trophy in 1685 (cf. Theiner, Vetera monumenta slavorum meridionalium historiam, Rome 1863, 2, p. 218). In the fortress, there was a palace that was used by Serbian and later by Venetian officials as their place of residence, and as a prison.

Interior of the Fortress of Shkodra

(Photo: Robert Elsie, March 2008).

Also recorded is a church of Saint Nicholas "in the famed city of Scutari," in which Queen Helena, the French widow of King Stephen Urosh I, was made a nun by the Monk Hiob (cf. Archbishop Daniel, Daničič edition, p. 84). In the cadastral register of 1416, it is referred to as San Nicolo apresso la porta. The other Catholic churches of Scutari were: Saint Mary across from the fortress, the Franciscan church (1395), the church of Saint Elijah in the Dominican monastery (1444), Saint Aponale, All-Saints (in Serbian: Sveti Vrači, i.e. the church of the holy physicians, Cosmas and Damian), and two churches that were in ruins in 1416: Saint Theodore and Santa Croce. The Serbs founded a monastery to Saint Peter in Scutari, subordinate to the metropolitan of Zeta, who was instituted by the patriarcha Sclavonie (1404, 1426) (cf. Ljubić 5, p. 43 and 9, p. 16). In the suburb called Sub-Scutari, Ragusan merchants lived near a church of Saint Blasius (extra Scutari ad Sanctum Blasium, 1433, S. Blasius prope civitaten Scutari, 1444). The houses in the city were made both of stone and of wood, with some of the roofs being covered only by wooden shingles or straw.

In the biography of Stephen the First Crowned (pre-1215), the fortress of Scutari is called Rosaf. Marinus Barletius (ca. 1480) refers to it under the name Rosapha. It is also mentioned by a number of writers in the nineteenth century. The fortress derives its name from a legend, a curious but not uncommon phenomenon. It comes from the now abandoned city of Rusafa, which is mentioned in the legend of the Roman soldiers, Sergius and Bacchus. Situated in eastern Syria in the deserts of the Euphrates not far from ancient Palmyra, its walls and buildings are well preserved. Below Scutari there was a famous monastery on the Bojana River that was dedicated to these two saints and the people ascribed the town from which the Syrian martyrs stemmed to the surroundings of the monastery (cf. Hilarion Ruvarac, Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini 49, p. 39-41, and my article Das christliche Element in der topographischen Nomenclatur der Balkanländer, in: Sitzungsberichte der philosophischen-historischen Classe der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna, 136. 11 (1897), p. 48-54).

Under the Nemanja dynasty, Zeta and Scutari were the territory of the successor to the Serbian throne. After the fall of the Serbian empire, the Balšić dynasty began to rule here, from about 1360. Later, in 1392, the Turks took George Stracimirović Balšić prisoner and did not release him until he agreed to surrender Scutari to them. The Turkish commander Shahin ruled over Scutari and Saint Sergius [Shirq] from 1393-1395. George managed to drive the Turks out two years later, but in April 1396, he was obliged to abandon Scutari, Drivasto, Dagno [Deja] and Saint Sergius to Venice. The Venetians held onto Scutari for 83 years, from 1396 to 1479. The Republic of San Marco was represented here by a capitaneus et comes. The Serbs endeavoured in vain to retake the town. They besieged Scutari twice, once at the end of 1421 under the Depot Stephen Lazarević, and a second time in 1422 under the Despot and then under his commander Mazarak, until Niccolò Cappello, who stood ready with the Venetian fleet near Saint Sergius, repelled the Serbs in a decisive assault on Dagno one night in December (cf. Jorga, Notes et extraits pour servir à l'histoire des Croisades au XVe siècle, 1 p. 329, footnote 4).

After the fall of the Christian realms of Serbia, Bosnia and Albania, the Turks advanced through this region once again. In 1474, under Sultan Mehmed II, the Beylerbey of Roumelia, Suliman, besieged Scutari, but the town was courageously defended by Antonio Loredano and his 2,500 soldiers, with the help of Venetian ships waiting in the Bojana and at sea, and with the support of the Crnojevići of Montenegro and the Albanian highlanders. The second siege in 1478, recorded by the priest Marinus Barletius in minute Latin script, was led by Sultan Mehmed II himself. The Venetians defended the town heroically but were forced to evacuate it after a peace agreement in 1479. Of their 1600 soldiers, only 450 remained. The population, under their leader Florio Jonima, departed and settled in Venice, Ravenna and Treviso. From that time until 1913, a period of 434 years, Scutari has been under Turkish rule.

The centre of old Scutari was the fortress (castrum), which was only accessible from one side. According to the description of Ippen, it is surrounded by double walls. Throughout the fortifications, one finds remnants of Venetian architecture. The old buildings were destroyed in a gun powder explosion in the nineteenth century. To enter, one passes through three gates, each in a tower, followed by three courtyards. In the central courtyard there is a mosque with remnants of a Gothic vaulted ceiling and sculptures (cf. Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini 1902, p. 181, and Wissenschaftliche Mitteilungen aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina, 10, p. 47 sq.). This was no doubt once the Cathedral of Saint Stephen (ecclesia cathedralis Sancti Stephani de Scutaro), that became famous in 1346 for its miracles (cf. Theiner, Vetera monumenta slavorum meridionalium historiam, Rome 1863, 1, p. 219). The Emperor Stephen Dushan gave the "millrace (jaz) of Saint Stephen" in Scutari to the Monastery of the Archangels near Prizren (cf. Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini 15, p. 288) when he seized the Catholic diocese during a conflict with the Latin Christians. The Turks transformed the old cathedral into a mosque. An old, broken-down organ (organo disfatto) still stood in the building as a trophy in 1685 (cf. Theiner, Vetera monumenta slavorum meridionalium historiam, Rome 1863, 2, p. 218). In the fortress, there was a palace that was used by Serbian and later by Venetian officials as their place of residence, and as a prison.

Also recorded is a church of Saint Nicholas "in the famed city of Scutari," in which Queen Helena, the French widow of King Stephen Urosh I, was made a nun by the Monk Hiob (cf. Archbishop Daniel, Daničič edition, p. 84). In the cadastral register of 1416, it is referred to as San Nicolo apresso la porta. The other Catholic churches of Scutari were: Saint Mary across from the fortress, the Franciscan church (1395), the church of Saint Elijah in the Dominican monastery (1444), Saint Aponale, All-Saints (in Serbian: Sveti Vrači, i.e. the church of the holy physicians, Cosmas and Damian), and two churches that were in ruins in 1416: Saint Theodore and Santa Croce. The Serbs founded a monastery to Saint Peter in Scutari, subordinate to the metropolitan of Zeta, who was instituted by the patriarcha Sclavonie (1404, 1426) (cf. Ljubić 5, p. 43 and 9, p. 16). In the suburb called Sub-Scutari, Ragusan merchants lived near a church of Saint Blasius (extra Scutari ad Sanctum Blasium, 1433, S. Blasius prope civitaten Scutari, 1444). The houses in the city were made both of stone and of wood, with some of the roofs being covered only by wooden shingles or straw.

The court of the Serbian kings and subsequent tsars was situated outside the town on the river Drimac, that Negri called Drynax and the Venetians Drinase. It is now known as the Drinassi or Kjiri [Kir]. This was the residence of the young king Stephen Dushan when he was at war with his father, Stephen Urosh III, in 1331. According to the account given in the biographies of Archbishop Daniel (cf. Daničič edition, p. 209), the father destroyed the vineyards, orchards and fields, "and ordered the court of his son below Scutari on the banks of the Drimac, with its many wonderful palaces, to be razed to the ground." After 1416, the Venetian cadastral register mentions la corte de lo imperador near Scutari. Jastrebov thought that the remnants of these buildings were the court of the Albanian Bushatli dynasty in Kosmač [Kosmaç] between Bušat [Bushat] and Dagno that were destroyed in the flooding of the Drin in 1881. In two of the halls, under the Turkish plaster, one could still see remnants of the old church murals with pictures from the Gospels (cf. Spomenik 41, p. 49-50). But according to Daniel, Dushan's court must have been nearer to Scutari, right on the banks of the Drimac.

From the eleventh century onwards, the Catholic bishop of Scutari was subordinate to the archbishop of Antivari. The bishops often undertook missions on behalf of the Serbian kings. In 1321, for instance, Bishop Peter was sent to Ragusa by Urosh II. On his episcopal seal was the Virgin Mary and Child (cf. Spomenik 11, p. 49-50). The comes of the town functioned as its political leader. Mention is made in 1347 of the comes Petrus Chranimiri. The city was known as the commune et universitas Scutari (1356), governed by judges and town counsellors (judices et consiliarii civitatis Scutari, 1401). Only Latin documents are preserved from the town chancery. Mention is made in 1330 of a Clemens filius Gini, notarius communis Scutari. There was a scribe for Serbian-language documents, who was also an interpreter, but only under Venetian rule. Scutari also minted coins with Latin inscriptions. King Constantine, the son of King Stephen Urosh II Milutin, who soon died in battle against his half-brother Stephen Urosh III (in 1322), issued five different coins. They had S. Stefanus Scutari written on one side, with the king on his throne and the inscription dominus rex Constantinus on the other. The coins minted in bronze have a picture of Saint Stephen on one side and a picture of the Saviour with the inscription civitas Scutarensis on the other. George Stracimirović issued silver coins here, too. They bear his image and that of Saint Stephen. He also issued 20 types of copper follari. The copper coins of the Venetian period have Saint Stephen on one side and Saint Mark on the other (cf. Dr. K. Stockert, Die Münzen der Städte Nordalbaniens, in: Numismatische Zeitschrift, 43 (1910), p. 67-128).

In Drivasto, Dulcigno and Antivari, there were many ancient Roman or Romanesque remains under the castles that can be recognized by the family names. But in Scutari the names are mostly Albanian in the fourteenth century. Mention is made in the archives of Ragusa and Cattaro of: 1220 Petre de Bercia, Andrea Span, Duchesa, Moisa Travalo; 1331 Guin nepos Petri Chranimiri; 1352 Progon Tuodori de Scutaro; 1370 Vita filius Duche; 1395 Tole de Paraviso etc., There were also nobles in the town: 1417 Ser Marinus, filius comitis Stefani de Scutaro, etc. Indeed, in the fifteenth century, there were quite a few nobles residing here who no longer wanted to return to their manors in the countryside because of the many wars. Many of these were proniars who were doing military service with their cavalrymen, initially under the Serbs and later under the Venetians. Trade and commerce flourished, in particular with Prizren and Novo Brdo [Novobërda]. From the interior came wax and silver, and from Scutari went cloth, sea salt, and salted fish from Lake Scutari. Near Scutari, the Bojana was dammed with fishing weirs and water mills. In 1422, the Venetians wanted to do away with them so that their naval vessels could reach Scutari itself.

The major source for our knowledge of the region is the catasticum, written in 1416 by the Venetian notary Petrus de Sancto Odorigo de Parma, a large codex of 172 folios preserved in the San Marco library in Venice. This cadastral register mentions all the inhabitants in the various settlements and the amount of taxes they owe. It was utilized by Makušev in his work, Istoričeskija razyskanija o Slavjanakh v Albanii v srednie veka, Warsaw 1871. An extract of this was published by Ljubić in the periodical Starine of the Yugoslav Academy of Science and Art, vol. 14. Shortly before his death, Miklosich was working on a complete edition, but he did not manage to complete it or get it published. Five years later (1421), the government of Venice ordered a catasticum novum for Scutari, Drivasto and Dulcigno, but nothing of it has been preserved. The territory of Scutari extended at this time from the coast between the deltas of the Bojana and the Drin to the village of Tuzi near Podgorica. It was divided into two districts: sotto Scutari [below Shkodra] and sopra Scutari [above Shkodra]. There were 114 villages (38 in the upper district and 76 in the lower district), with a total of 1,237 houses. Most of the names of the villages exist today. For instance, near the town was Lubani (now Jubani), Valcatani (now Vukatani), Spatari (now the same), Cusmaci (now Kosmač). The village of Ulijari (the "beekeepers") in sopra Scutari has vanished, in which Constantine, the son of George Balšić and Theodora, a sister of the Despot Dragaš (cf. Spomenik, 11, p. 15), issued a deed to the Ragusans in 1395 (cf. Miklosich, Monumenta, p. 228). Of the larger towns, the ones that have survived are Scutari, Alessio and Dulcigno, all three founded before the Roman period. It is curious how many of the smaller towns have disappeared since the fifteenth century, in particular the six episcopal sees: Balezo, Drivasto, Sarda, Dagno, Sapa and Svač. This phenomenon occurred in two regions of the peninsula: in Thrace, between Galipoli and Adrianople, as a consequence of the Turkish conquest when the Ottomans crossed over into Europe (1354), and in Albania in the area of Durazzo and Scutari as a consequence of the Great Turkish Wars of the fifteenth century against Venice and Scanderbeg.

The main fortress in the region was situated ten kilometres east of Scutari in the valley of the Kjiri [Kir] River, in the mountains of Albania. This was Drivasto, called Drivastum in Latin and Drivost in old Serbian, as mentioned by King Stephen the First Crowned and Thomas the Archdeacon of Spalato [Split]. On the fifteenth-century Venetian map of Fra Mauro it is called Drieuasto. The fortress may stem from the Illyrian or Roman period. In Albanian it is now called Drišti [Drisht]. The ruins have been described by Gopčević in Oberalbanien und seine Liga (Leipzig 1881), p. 152 sq., by Ippen in Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini, 1900, p. 520-631, as well as in Wissenschaftliche Mitteilungen aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina, 10, p. 9-16 (with illustrations and maps), and by A. Degrand in Souvenirs de la Haute Albanie (Paris 1901), p. 88 sq. The settlement is situated on a hill about 150 metres high, that is bordered to the north and west by the deep valley of the Kjiri, and to the south by the ravine of the Proni Drištit [Proni i Drishtit] Creek. As such, it can only be approached from the east. In the middle of the hill is the village of Drišti with a mosque and the remnants of the old town with two gates. About 60-80 metres above the village, at the peak, is the old fortress Kalaja Drištit [Kalaja e Drishtit], surrounded by walls in an irregular polygonal shape, with the remains of the towers. Between the town and the fortress are the ruins of a small chapel with two round altars. Near one gate is a stele with a coat of arms, with three stars. From the ruins, there is a good view of Scutari and the lake. Barletius praised the good water and the good air of Drivasto.

In the older catalogues of the Greek bishops it appears as ὁ Δριβάστου subject to the metropolitans of Durrës. However, in the eleventh to fifteenth centuries, it was subject to the Catholic archbishop of Antivari. Drivasto was long under Byzantine control until Nemanja took it when he seized Scutari. Under Serbian rule, the town remained a privileged settlement with elected officials and local laws of its own. The king was represented by a comes (1251). In 1242, when the Tatars advanced from Hungary down through Dalmatia, and returned to Russia via Serbia and Bulgaria, the towns of Svač and Drivasto were pillaged and the inhabitants killed, as a contemporary, Thomas the Archdeacon of Spalato, informs us. From 1393-1395, Drivasto and Scutari were in the possession of the Turks, but in 1396, they fell to the Venetians. The Republic confirmed the town’s antiqua statuta, settled the border between it and Scutari, and promoted the sale of the local wine by banning foreign wines (cf. Ljubić 4, p. 408, and 5, p. 7). The commander of the comitatus Drivasti was a Venetian podestà (potestas). Balša III endeavoured to retake the town. During a lengthy siege in 1418, the defenders of the town were brought to the brink of starvation and thirst, and the local commander Correr had only 40 men left to defend it. Balša finally broke into the town on a very rainy day in September, losing none of his men, and made the podestà, with his wife and soldiers, his prisoner (cf. Jorga, Notes et extraits pour servir à l'histoire des Croisades au XVe siècle, 1 p. 394, footnote). In 1421, the troops of the despot took Drivasto, a move that the Venetians did not appreciate quia sine Drivasto civitas Scutari parum valet (cf. Ljubić 8, p. 118). The Serbian despots held Drivasto until 1442. A detailed border agreement between Venice and Serbia was signed in Drivasto in November 1426. The Venetians then took Drivasto for a second time and held it for 36 years, from 1442-1478, after confirming the privileges previously accorded to the town (cf. Ljubić 9, p. 157-159).

The Gates of Drisht, formerly Drivasto

(Photo: Robert Elsie, November 2010).

A clear distinction was made between the fortress and the town (castrum et civitas). The cathedral was a church dedicated to Saint George. Mention is also made of a church dedicated to Saint Mary, seat of the cathedral chapter (capitulum ecclesiae S. Mariae de Drivasto, 1352), and of a church dedicated to Saint Francis. Subordinate to the bishop were many clerics, canons, an archpriest and other priests, but because of the low level of income, many of them served in the town of Ragusa or in its surroundings. For example, in 1317, one cleric, Andrew from Drivasto, was a notary on the island of Lagosta [Lastovo]. Few details are known about the organisation of the town (communitas) itself. Its Latin-language documents were written by a notary who was also a cleric. In the vicinity of the town there was sufficient wine and oil, but more and more distress was caused by the never-ending wars. Barletius reports that in the fifteenth century the citizens of the town proudly regarded themselves as descendents of the Romans (romanorum colonos se appellantes), and indeed, in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries there were many pure Roman family names among them: Palombo or Colomba, de Leporibus, Barbabiancha, Summa, Bello. In addition to these, however, there were also Albanian names: Bariloth, Precalo, Scapuder (1368). The latter would seem to be the earliest trace of the ethnic designation of the Albanians - Skipetar. There were also Serbian names such as Berivoj, and Greek names such as Calageorgii and Spano (σπανός = beardless). One of the most prominent noble families was called Span or Spano, in Serbian Spanovići. Some of them were in Venetian service in the fifteenth century. Others supported the Serbs. One figure who appears often in the archival documents of Ragusa is Peter Span, a Catholic Albanian (1430-1456) who died before 1458. He had three sons: Božidar (who died before 1474); Alexius filius Petri Spani or Lješ Spanović, who was voivode of the Despot George in the mountain settlement of Novo Brdo in 1454 and was still alive in 1474; and Hrvoje who was still alive in 1478. After 1474, we come across Božidar’s son Peter, his mother Gojsava and his wife Ljubosava. In the sixteenth century, the Venetians called the mountains behind Drivasto, north of the Drin, the monti delli Spani, and the mountains south of the Drin the monti delli Ducagini (cf. Starine 12, p. 196). The town of Drivasto also minted rather primitive copper coins. On them one can see the town with its towers and a gate with a lily. The inscription is civitas Drivasti is not clear (cf. Stockert, Wiener Numismatische Zeitschrift, vol. 43, 1910, p. 117).

Some of the geographical terms used in the area are Roman: fundina (fontana), cruce (crux) in 1402. At the foot of Mount Maranai (called Marinaa or Marinay in the fifteenth century) was the Benedictine monastery of Saint John which in 1356 the Pope placed under the jurisdiction of the bishop of Balezo (cf. Theiner, Vetera monumenta slavorum meridionalium historiam, Rome 1863, 1, p. 236). Later it belonged to the zone of Drivasto in a region called Stole (cf. Ljubić 9, p. 158) or Strilalio. Its abbot was always to be a man from Drivasto (semper in futurum abbas sit Drivastinus). The ruins thereof, including a tall square tower and the remains of the church and monastery, are to be seen on the field of Shtoj, north of Scutari. In the nineteenth century there was a major dispute here in the ruins of the church of Saint John of Rashi between the Catholics and Orthodox immigrants from Montenegro (cf. Ippen, Wissenschaftliche Mitteilungen aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina, 8, p. 141-143 with ill., and Degrand, p. 81).

During the final siege of Scutari in 1478, the Turks conquered Drivasto and took 300 men of Drivasto prisoner. Sultan Mehmed II had them all decapitated under the walls of Scutari in order to terrify the Venetians and force them to surrender.

From Scutari, after crossing the plain in the direction of Prizren for two and a half hours, one reaches the Drin River at the site where it emerges from the mountains. On the left, southern bank of the river, there rises a bell-shaped hill with the remains of an old fortress on it which the Albanians call Dajino [Deja]. At the bottom of the hill is the small settlement of Vau Dejns [Vau i Dejës], meaning the ford (vadum) of the Deja. Here there is a church dedicated to Saint Mary that serves presently as the parish church of the village of Lači [Laç]. It is a solid structure with a lofty vault, but its frescos have alas been severely damaged. New frescos have been painted over the old ones, and some of the inscriptions are in Latin, others in Greek (cf. Hahn, Reise durch die Gebiete des Drin und Vardar, pp. 36, 328; and Ippen, Wissenschaftliche Mitteilungen aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina, 7, p. 240 sq. with ill.). It was here that the Drin was forded with large primitive dugouts as described by Boué (they were called pareço and ladia in the Ragusan reports of 1377) and it was here that the roads from Scutari and Alessio came together, to continue eastwards to Prizren.

The fortress is well-known from fourteenth and fifteenth-century records. In Latin it was called Dagnum (also mercatum Dagni, de Dano, de Dagno), in Italian Dagno, and in Serbian Danj. King Stephen Urosh III issued commercial privileges to the Ragusans here in 1326 (na Dani). In 1348, the Emperor Stephen Dushan bequeathed the church, located below the fortress, to his Monastery of the Archangels near Prizren: “the church of Danj of the Holy Mother of God with its inhabitants and land, and the village of Prapratnica and the village of Lončari” (document given in Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini 15, p. 304). In 1361, under the reign of his son, the Emperor Urosh, there was a Latin bishop in Dagno who was subordinate to the archbishop of Antivari. Farlati records that this succession of bishops lasted until 1520, although they later only held the title and did not actually live there. The customs office of Dagno (carina na Dani, Danju) is often referred to in the Balšić period. In 1396 George Stracimirović ceded Scutari and Dagno to the Venetians, but before the actual handover, the nobleman Coya Zaccaria, who called himself Lord of Sappa and Dagno (dominus Sabatensis et Dagnensis), seized the fortress from him. For some time around 1431, there was a Turkish governor (kefalija) here. Later, in 1444, Coya’s daughter, Lady Bolja or Boja, handed the fortress of Dagno, fortified with seven “bombards,” the fortress of Sati and other places over to the Venetians (cf. Ljubić 9, p. 443). In 1447, Scanderbeg then seized Dagno from the Venetians, but gave it back to them in 1448. In 1456 the Dukagjin family got it, but in 1458 Leka Dukagjin and his brothers returned it once again to the Venetian authorities. In 1456, Lady Boja complained that the Pope had given the chapel of Saint Mary’s under Dagno (capellam Sancte Marie subtus Dagnum) to a Latin priest (cf. Ljubić 10, p. 91). The Republic replied that she could not contravene papal bulls and should apply to the Pope himself. The surroundings of Dagno were well populated at the time, with a number of villages, and old and new vineyards.

Further to the east, on the right bank of the Drin in the gorge, near the village of Mazreku, there was a church 27 paces long with a tower, the remains of an old monastery. An inscription mentions King Urosh (rex Vros) and the abbot (abas) of the monastery with all his clergy (cum universo suo clero). The building has been described by Jastrebov (cf. Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini, 48, p. 381) and Ippen (cf. Wissenschaftliche Mitteilungen aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina, 8, p. 131 sq.), who calls it the Church of Saint Nicholas of Sati.

Across from it, two hours from Scutari on the left bank of the Drin, are the ruins of a settlement with a fortress standing on the rocky promontory of a peninsula surrounded by the river on three sides. One can still see the remnants of the square towers on the town walls, the gateway to the fortress, and ruins of churches that were all simple constructions, devoid of ornaments. This was the episcopal settlement of Sarda, subject to the archbishop of Antivari (cf. Degrand, p. 110 sq., and Ippen, Wissenschaftliche Mitteilungen aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina, 8, p. 134 sq. with ill.). The bishops of Sarda (episcopi Sardenses or Sardanenses) are mentioned in the period from 1190 to 1460. By 1290, however, the church of Sarda (ecclesia Sardanensis) was referred to as inter nationes perversas posita (cf. Theiner, Vetera monumenta slavorum meridionalium historiam, Rome 1863, 1, p. 109). Sometime the bishops also bore the title of Lesser Pult (Polatum minus), a region in the near-by mountains, but later the diocese was united with Sapata [Sappa]. Nemanja’s son, King Stephen the First Crowned, refers to a settlement called Sardonikij among those between Dagno and Drivasto that his father had conquered. This should probably read as grad Sardon(s)kij (the town of Sarda). The ruins are now called Shurda or Shurdha [Shurdhah].

Let us now turn to the roads leading from Scutari to the sea, i.e. to the estuaries of the Bojana and the Drin.

On the right bank of the Bojana, we first come across the settlement of Oblika at the foot of Mount Tarabosh (572 metres high). This was the site of the fortress of Obliquus, where, according to Presbyter Diocleas, the Emperor Samuel of Ohrid surrounded the Serbian prince Vladimir and took him prisoner. In 1398 we find Oblich partium Schutari mentioned in the archival records of Ragusa. In the fifteenth century, Gojčin Crnojević demanded Oblich from Venice, which his ancestors had received from the lords of Zeta (per i segnori de Zenta) (1444 and 1452, cf. Ljubić 9, p. 202). Further down the river is the village of Trunši [Trush], formerly known as Trunsi or Trompsi, situated on the island of Saint Sergius (insula Sancti Sergii) that remained loyal to Venice in 1423.

The principal settlement on the Bojana was the Benedictine monastery of Saint Sergius and Saint Bacchus on the left or southern bank of the river, 18 miles from the estuary and six miles (one and a half hours) from Scutari. We do not know when or by whom it was founded. The adoration of these Syrian saints reached its zenith in the sixth century under the Emperor Justinian who dedicated a large church in Constantinople to these martyrs. Presbyter Diocleas reports that the graves of the kings of Doclea were to be found at the abbey of Saint Sergius in the eleventh and twelfth centuries – Michael, Bodin and their successors. Latin inscriptions have survived here on the reconstruction of the church under Queen Helena and her sons, King Stephen Dragutin and King Stephen Urosh II (Milutin), in 1290 and 1293. The best photo reproduction of the remains are by Ippen (cf. Wissenschaftliche Mitteilungen aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina, 7, p. 232). Near the monastery there was a harbour for merchant vessels, a customs house and a warehouse for storing salt. For this reason, the site often comes up in mediaeval documents, in particular those of Ragusa, that call it Sanctus Sergius, San Serzi or portus Sancti Sergii de Drino (Oldrino), and in Serbian as Sveti Srgj. The market fair (panagjur) of Saint Sergius is also referred to in 1377. Cloth and wine were imported here from Dalmatia and Italy. Sea salt, wood, wax, lead and silver from Serbia as well as fish from Scutari were among the exports. Among the officials serving the kings of Serbia were, for instance, a representative of Queen Helena here in 1280 called baiulus domine regine ad portum Sancti Sergii, and a certain Bogdaša who was castellanus Sancti Sergii in 1335. From the salt deposits here, the monasteries of Vranjina, Banjska and Prizren received annual endowments of salt, according the golden bulls of the Serbian kings and emperors. In 1393-1395, during the struggle between the Turks and George Stracimirović, Scutari and Saint Sergius were under the command of Shahin, the Turkish captain (capitaneus turcorum). George managed to drive the Turks out, but in 1396, he gave the site to the Venetians. The port of Saint Sergius on the Bojana was of great significance in the wars waged by the Republic of San Marco with Balša III and the Serbian despots. Here lay the Venetian galleys to defend Scutari. In 1423 a provisory fortification in the form of a wooden palisade was constructed here (bastita a latere S. Sergii). In July 1423, George Branković, the nephew of the despot Stephen, turned up with 8,000 horsemen, but by August of that year a peace treaty was signed in the camp at the bastita there between Venice and Serbia (cf. Čedomilj Mijatović, Despot Đurađ Branković, gospodar srbima, Belgrade 1880, 1, p. 40). According to the treaty, the Venetians retained Scutari, Alessio, Dulcigno and Saint Sergius. The Serbs got Drivasto, Antivari and Budua. Saint Sergius was later an important base for the Venetians when the Turks began to storm Scutari.

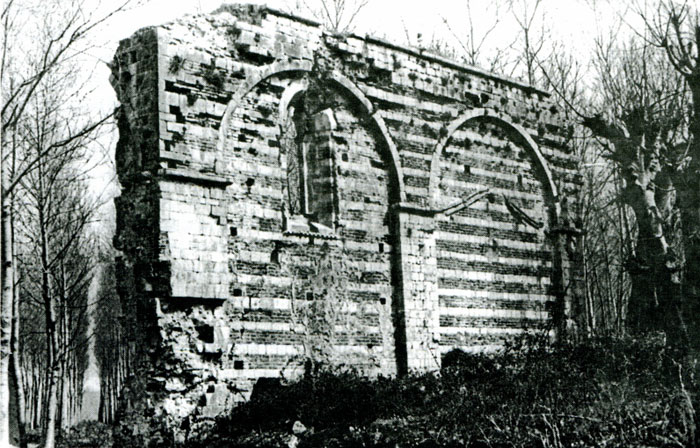

Remains of the church of Saint Sergius

and Saint Bacchus in Shirq.

Trade flourished at Saint Sergius in the Turkish period, too, because it was here that the ships and caravans met. In 1685 at beautiful bell tower (bellissimo capanile) could still be seen next to the church and provided an excellent view of the surrounding plains (cf. Theiner, Vetera monumenta slavorum meridionalium historiam, Rome 1863, 2, p. 218). Today, the church of Saint Sergius is a sad ruin. One encounters a large construction with three naves and three altars, walls with alternative layers of stone and brick, the remains of mosaic floors and remnants of old frescos in two layers, one on top of the other. The roof is missing, and trees are growing in the interior of the church. To one side, the foundations of the walls have been greatly hollowed out by the Bojana. Nearby is the small village of Širč or Širgi [Shirq]. Descriptions of the site have been made by Jastrebov (cf. Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini, vol. 48) and in greater detail with illustrations and a map by Ippen (cf. Wissenschaftliche Mitteilungen aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina, 1900, p. 231 sq.). and Degrand, (p. 93 sq.).

In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the zone north of the Bojana was called Zabojana (i.e. behind the Bojana). The most important port on the river nowadays is Oboti on the right bank, which was perhaps the site of the fifteenth-century scala, called locus scale in 1423, scala or stretto (cf. Ljubić 8, p 242, 250). The village of Samriši [Samrisht], formerly Samarisi, on the left bank, was an old farm belonging to the Gjuraševići or Crnojevići family, but the Venetians would not give it back to them and preferred to give it to their loyal followers, the noble Albanian Pamalioti family (cf. Ljubić 9, p. 202, 435). Further along the right bank is the village of Gorica inhabited by Albanian Christians. It was called Gariza by Presbyter Diocleas and Santa Maria de Goriç de Ludrino in the chancery roles of Ragusa in 1387. Wood for export was loaded onto the ships here. Then came Sanctus Petrus de flumine Drini (1278) and the church ecclesia Sancti Theodori in flumine Drini (1282, 1374). There was a place here to cross the Bojana, referred to as San Todoro, passo di Bojana (cf. Ljubić 10, p. 11), just as there was at the next village Belleni or Bellani, now called Belen or Belaj, on the left bank.

Lake Shas (Šasko jezero) in Montenegro

(Photo: Robert Elsie, April 2009).

On the right side, the river Megjureč flows into the Bojana. It comes from Lake Saš [Shas] that is half an hour from the Bojana. The lake is really only the extension of the riverbed. According to Rovinskij it was at times 500 metres long and after heavy rainfall could be almost four kilometres in length. The upper part of the lake is marshy and unhealthy. There are woods on right bank of the lake, whereas the left bank is stony and barren, with the ruins of an ancient town. This was the site of Svač [Shas], called Suacia or Soacia in Latin and Suaço or Soaço in Italian. It was the seat of one of the bishops in the archdiocese of Antivari, the episcopus Suacensis, Soacensis, or Soacinensis. Farlati notes that this title was used from 1067 to 1530. Svač belonged to the Serbs from the time of the Nemanja dynasty. It was destroyed by the Tatars in 1242, reconstructed, but began to decline before 1400. Very little is known about its population and municipal administration. The town minted bronze coins with a portrait of Saint John the Baptist on one side and a high vaulted loggia and tower with the inscription Sovaci civitas on the other (cf. Stockert 1. c. 119). The city walls were in such bad shape in 1406 that the bishop, as the city’s envoy in Venice, requested permission to fortificare et murare locum illum (cf. Ljubić 5, p. 77) because the Turks were pillaging in the region. In 1413 the Ragusans gave the bishop bricks to roof the church. By the sixteenth century, the town was abandoned and empty. Giustiniani wrote in 1553 that the walls and towers of the antichissima città detta Suazzi were still intact, but the moat in front of the walls was dry and inside the town were the ruins of 360 (!) churches and chapels (cf. Ljubić, Commissiones et relationes venetae, 2, p. 231). Even today, the farmers in the surrounding area insist that there were only churches in the town. They call the ruins Kishat (meaning “churches” in Albanian) or Shas, a name which is also used for the impoverished Muslim village nearby. The city walls with two towers can also be seen, as can the remains of some churches, including the ruins of a large church with an altar in the belfry and the ruins of a church with bits of paintings and the grave of a Bishop Marcus who died in 1262 (cf. Ippen, Wissenschaftliche Mitteilungen aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina, 7, p. 235 sq., and new illustrations in Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini, 1902, p. 552 sq. and in Wissenschaftliche Mitteilungen aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina, 10, p. 42 sq.)

Church ruins in Shas (Šas) in Montenegro

(Photo: Robert Elsie, April 2009).

Further down the river are villages mentioned in the cadastral register of 1416: Penetari, now Pentari; Precali, now the same [Prekal]; Luarisi, now Luarsi [Luarzi]; and Reci, now Reči [Reç]. At the mouth of the Bojana on the left side was the village of Polani or Pulani, now called Pulaj. On the right side was an old Benedictine monastery belonging to the diocese of Dulcigno, San Nicolo de Boiana or San Nicolo de Drino (Oldrino), also called the abadia di San Nicola de la foza (the latter word derives from the Latin fauces “gorge, mouth”) (cf. Ljubić 9, p. 10). The name of the monastery appears in the name of the Albanian village of Šinkol [Shënkoll], called San Nicolo in Italian. Previously, before the Middle Ages, the mouth of the Bojana was farther north, nearer to Dulcigno where Lake Zogaj is now situated in a warm and fertile environment full of woods, grain and fruit.

The mouths of the Bojana and the Drin are situated about twenty kilometres from one another. The region between them, with hills rising to a height of 551 metres, was densely wooded in the Middle Ages, and is now completely barren. The present seaport for Scutari is situated here on the coast, the settlement of San Giovanni di Medua, referred to in 1336 as portus Medue; in Ragusan documents in 1414 as Miedua, portus Alesii; and on the map of the Italian Benincasa in 1476 as Medova. The harbour is the same one as the tutissimus portus of Nymphaeum in antiquity, which Julius Caesar (De bello gallico) referred to as being three Roman miles (4½ kilometres) from Lissum [Lezha]. In 1449, Scanderbeg demanded the settlements of Medoa and Vilipolje [Velipoja] from Venice, and the Republic gave them to him so that he could let his flocks graze on Venetian territory (cf. Ljubić 9, p. 312). The cadastral register of 1416 mentioned many villages here: Barbarossi, now Barbaluši [Barbullush] on the right bank of the Drin, Chacharichi, now Kakariki [Kakarriq], Baladrini, now Baldrin [Balldren], Renisse in la Medoa, now the 551 metre high mountain Mali Renzit northwest of Medua, etc.

The Drin, also called the flumen Lessi (Alexii) was much less important than the Bojana in the Middle Ages. We have no information of commercial vessels sailing up the Drin as far as they did up the Bojana. The area around Dagno was called Rogamania and, according to documents from around 1460, included the villages of La Virda, now Vjerda [Vjerdha], Lissani, now Lisna [Lisna], Dodice, now Dodej, and Medoia, now Mjeta [Mjeda] (cf. Ljubić 10, p. 138, 295). Next, on the left bank, was the region of Zadrima “behind the Drin”, known from the fifteenth century. In 1459, it was also called the “field of Sati” (pian del Sati) (cf. Ljubić 10, p. 138), with the fortress of Sati (castrum Satti, Satum, Sat, castello di Sati) at the foot of the monte de Satti. The fortresses of Dagno, Sati, Sapata and the regions of Rogamania and Zadrima belonged at the time to the Zaccaria dynasty and later to the Dukagjin [Dukagjin] family. There is also a village called Nden Šat or Nenšat [Nënshat], i.e. “below Shat” (cf. Hahn, Reise durch die Gebiete des Drin und Vardar, Vienna, 1867-1869, p. 328). The main settlement here was Sapa or Sapata, and the episcopus Sappatensis, who had his seat here, was a suffragan of the diocese of Antivari. In 1291, the inhabitants of Sava civitas rebuilt the town and asked for a bishop, which the Pope accorded to them after requests from the archbishop of Antivari and Queen Helena (cf. Theiner, Vetera monumenta slavorum meridionalium historiam, Rome 1863, 1, p. 111). The names of the settlements in this area are well known from the treaties concluded between Venice and the Dukagjin family: Aimelli, now Hajmeli [Hajmeli], Scaramani, now Šaromani near Nenšati, and Fontanella, a Roman name, etc. In 1452, mention is made of the village of Gladri and the fiume del Jadro, the present-day river Gjadri. The Emperor Stephen Dushan gave to the Monastery of the Archangels near Prizren a church of the Virgin Mary and an orchard on the “Gladra,” as well as the village of Žeravino which was a pronia (fief) of the Zaccaria family in the fifteenth century (cf. Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini 15, p. 304, 310, and Starine, 14, p. 55). In 1490, the diocese of Sapata was joined to that of Sarda, and they remain united today. From a description left in 1685, a few remains of walls were left in Sapa at the foot of the mountain of the holy archangel (vestigi delle sole muraglie della città di Sappa alla costa del monte detto S. Angelo, cf. Theiner, Vetera monumenta slavorum meridionalium historiam, Rome 1863, 2, p. 219). Nowadays, this mountain is called Saint Michael’s mount, with the ruins of a church. At the foot of the mountain, one can see the site where Sapa once stood. Half an hour further on is the present residence of the bishop of Sapata, who is responsible for the Catholics of Zadrima and Dukagjin, over 2,000 homes (cf. Hahn, Reise durch die Gebiete des Drin und Varda, Vienna, 1867-1869, p. 328).

The Fortress of Lezha, formerly Alessio

(Photo: Robert Elsie, March 2008).

Nearer to Alessio was the settlement of Suffada (Zufada) where salt and wood were loaded onto ships. In a Venetian document of 1393, it was said to be eight miles from Alessio. In a letter from Prince Ivan Kastriot to the Ragusans, dated 1420, it was called Šufadaj. It was from Šufadaj, through Ivan’s territory, that merchants journeyed to the land of the “Lord Despot” to Prizren (cf. Archiv für slawische Philologie, 21, p. 95). In 1368 the three Balšić brothers sent a letter to the Ragusans “below the Široki Brod (wide ford) at Lješ [Lezha]” (cf. Miklosich, Monumenta, p. 177). This site may have been identical to Šufadaj because the monasteries of Banjska and Prizren received annual endowments of salt from the salt reserves in Široki Brod.

Six hours below Dagno, on the south bank of the estuary of the Drin, is the town that both the Albanians and the Serbs call Lješ [Lezha]. It was known as Lissos to the ancient Greeks, as Lissum to the Romans, as Elissos to the Byzantines (in the catalogues of the diocese, by Constantine Porphyrogenetus and by Anna Comnena), as Lessium (or Lexium, Lessum) in Latin in the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries, as Alexium or Alessium in the fifteenth century, and as Alessio in Italian. There is an ancient quadrangular fortress on a 200 metre high hill that is accessible only from the eastern side. Below it is the town on the river. According to Diodorus, Dionysos the Elder, the “tyrant” of Syracuse, founded a Greek colony at Lissos in 385 B.C. Its fortress, known from the reports of Polybius, was called Akrolissos. Hahn noted the ancient foundations of the fortress walls as being of huge stone blocks like the “cyclopean” walls of Greece. The people of Lissos also minted coins with Greek inscriptions on them. Later, it was the Illyrians who reigned here. Under the Romans, Lissum was the southern-most town of the province of Dalmatia, and the starting point of the great road leading to Salonae, Naissus (Niš) and Dyrrhachion. During the Norman wars, Anna Comnena praised the sturdy position of the impregnable castle from where the Byzantines provided Dyrrhachion with food and weapons by sea during their struggle against Bohemond. The town is not mentioned in the Nemanjid period, but it soon appears as a possession of the Serbs. The bishop, previously subordinate to the metropolitan of Dyrrhachion, later belonged to the Latin church (episcopus Lessiensis from 1371 onwards). In commercial records, Alessio is rarely mentioned, curiously enough. The Balšić often resided here. Two brothers of the Dukagjin family, Progon and Tanussius, gave the town to the Venetians in 1393. At that time, Alessio was considered the “right eye of Durazzo” (dexter oculus Durachii, cf. Ljubić, 4, p. 305). In 1468, when Scanderbeg, whose Christian name was George Castriotta, died, he was buried at the church of Saint Nicholas in Alessio. When the Turks took Alessio in 1478, they broke into his grave and seized the bones of the famous Albanian leader, spiriting them off in all directions as talismans. Farlati reports that mention was made of five churches here: Saint Nicholas (perhaps in the fortress), later transformed into a mosque; Saint George (in ruins); Saint Sebastian; Sancta Maria a Nivibus (the Turkish armoury); and Sancta Maria ab Angeli salutatione. Outside the town were Sancta Margarita and Sancta Maria, the Franciscan church. The Franciscans now live on the other side of the river in the monastery of Saint Anthony. In the Turkish period, the Catholic bishop of Alessio who was also responsible for the tribes of Mirdita, had his residence outside the town, in the village of Kalmeti [Kallmet]. Inside the fortress are the ruins of the palace of the one-time bey of Alessio (cf. Ippen, Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini 1902, p. 182, and Wissenschaftliche Mitteilungen aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina, 10, 52 sq. with illustrations). The sea in front of the estuaries of the Drin and the Bojana was known to the Venetians in early modern times as il golfo dello Drino.

[Konstantin Jireček, Skutari und sein Gebiet im Mittelalter, published in: Ludwig von Thallóczy (ed.), Illyrisch-Albanische Forschungen, Munich & Leipzig 1916, vol. 1, p. 94-124. The modern toponyms have been added in this text in square brackets. Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.]

TOP