| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1920

Sejfi Vllamasi:

Political Confrontation in Albania

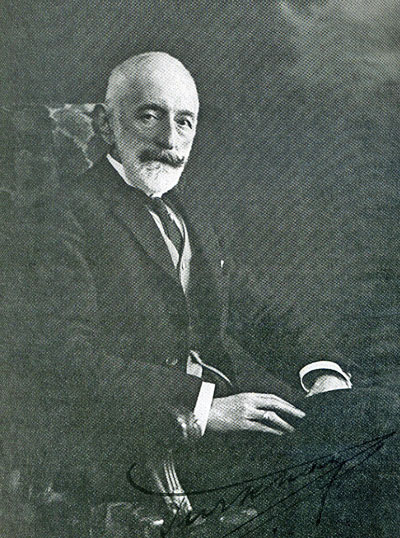

Sejfi Vllamasi (1883-1975). Photo ca. 1923.

Sejfi Vllamasi (1883-1975), from Novosela near Kolonja, was a political and nationalist figure of the independence and Zogist periods. He was a founding member of the Committee for the National Defence of Kosovo (Kosovo Committee) in 1918. In March-April 1919, he was part of an observer mission sent to the Paris Peace Conference, and was made a senator after the Congress of Lushnja in January 1920. In 1921-1923, Vllamasi was a member of parliament for Kolonja and nominally headed the People’s Party, known as the Clique. In May 1923, he was minister of public works and soon thereafter minister of the interior for a short time under Ahmet Zogu. Vllamasi subsequently became an opponent of Zogu and went into exile in 1924. He returned to Albania in 1939 and joined the ‘Balli Kombëtar’ resistance organization in 1943. After the communist takeover in November 1944, he was sentenced to ten years in prison, of which he served nine. He was thereafter sent into internment, and worked as a lowly herdsman and, later, as a veterinary at a slaughterhouse in Fier. His political memoirs, from which the following excerpts covering the period 1912-1920 are taken, are simply written, but contain many interesting first-hand observations on political life in Albania at the time.

The Declaration of Albanian Independence on 28 November 1912

When Ismail Qemali arrived in Vlora, Seit Qemali, Murat Tërbaçi, Alem Mehmeti and many other patriots were busy fighting as reservists against the Greek army on the Llogara Pass. When they found out why the Old Man had come, they raised the Albanian flag on the frontline, before it was raised in Vlora.

At the same time, representatives of the population, with a lot of patriots among them, were arriving from all over Albania and from abroad, and on 28 November 1912, with great enthusiasm after 450 years of enslavement, they raised the Albanian flag and declared Albania independent.

A government was formed under Ismail Qemali in which Preng Bibë Doda was made deputy prime minister and Essad Pasha Toptani became minister of the interior.

The jurisdiction of this administration covered Berat, Skrapar and Elbasan because the Turkish army was still in Fier and Lushnja, waiting to board ships to return to Turkey.

The Duke of Montpensier of the French Bourbon family, a man of considerable means, encouraged by Albert Ghica and inspired by his own ambition, sailed on his yacht from Brindisi in the company of Mark Kakarriqi and Pjetër Goxhamani and, breaking through the Greek naval blockade, arrived in Vlora where he presented himself as a candidate for the Albanian throne. Ismail Qemali accepted his candidature in principle, but wanted to await the reaction of Paris and London. In the company of Isa Boletini dressed in national costume, of Luigj Gurakuqi and of Pandeli Cali, Qemali set off for Brindisi with the duke and continued on to Paris and London where he was informed that international opinion now favoured Prince Wied as monarch. Taking advantage of the occasion, he appealed to the French and British governments and managed to get the Greek naval blockade of the Albanian coast lifted.

Essad Toptani arrived in Vlora but since the situation was not suitable for his further ambitions and for making a living, he returned to Durrës two days later where he set about to form a government of his own.

A plot was underway in Vlora to assassinate Essad, but Isa Boletini withdrew from it after talks with Ismail Qemali because the latter was strictly against any such moves. Qemali opposed all political killings as a matter of principle.

As usual, plots and conspiracies also began to thicken against the Vlora government. Bektash Cakrani, who was said to have accepted money from Greece to expand its borders to the detriment of Albania, gathered men and threatened to rise against the Vlora government. Behind him was probably Qemal bey Vrioni because he had attempted, unsuccessfully, to have Cakran made the capital of a sub-prefecture. But the government swiftly sent a force against him, commanded by Sali Vranishti and Hysni Toska, which overcame his men and burned down the houses and shops there. Bektash Cakrani was also involved in a conspiracy with Essad Toptani.

Secondly, Dervish bey Biçaku, a confidant of Essad Toptani and a sworn enemy of his own cousin, Aqif Pasha Elbasani, who at that time was the prefect of Elbasan in the Vlora government, gathered a force of men in October 1913 and rose against the government, inciting the people to rebel, and using the Koran as a means of inciting them. A force of men was also sent out against him under the command of Hysni Toska who, with the help of Aqif Pasha’s men in Gododesh, vanquished Dervish Biçaku so overwhelmingly that he lost his horse, his field glasses and his Koran on the battlefield. Biçaku continued to spread word from village to village that Prince Wied and Aqif Pasha were enemies of Islam.

The inhabitants of the Pindus mountain range supported the unification of the Pindus region with Albania. Their leaders, who spent the winter with their flocks in Konispol and Delvina, elected a commission and sent it to Vlora to tell Ismail Qemali that the inhabitants of the Pindus were resolved to link their destiny with that of Albania and were, to this end, ready to fight with the Albanians against Greece. Qemali accepted their support in principle, but Fejzi Alizoti found out and informed the International Control Commission that took position against Qemali.

At this time, the Young Turks sent Captain Beqir Grebena and four or five men to Albania to drum up support for a Turkish prince to rule Albania. Their candidate was Izzet Pasha of Serfije, former minister of war and a man of Albanian origin. The Young Turks were doing this to ensure that Albania would remain a vassal of Turkey and that Turkey would not suffer fatally from the independence of Albania. Beqir Grebena used legal means to reach his end, but was not adverse to a coup d’état. Fortunately he was stopped, and he and all of his men were arrested in Vlora by the Control Commission. The Commission set up a special court under General De Veer, head of the Dutch Military Mission seconded to organise the Albanian gendarmerie. Among the members of the latter were Captain Kasëm Sejdini, Captain Xhavit Leskoviku and two other civilians.

Syrja bey Vlora and Jorgji Çaku, a well-known and well-educated jurist, set off for Vlora from Istanbul where they were advised by the Young Turks to work with Ismail Qemali to put Izzet Pasha on the Albanian throne. However, these two men went first to see the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador in Istanbul to inquire about Austro-Hungarian wishes with regard to the Albanian throne and, later, when they got to Vlora, they testified against Qemali, whose collaboration with Beqir Grebena was proven by the special court in Vlora.

Ismail Qemali was a supporter of the Entente, i.e. of the British and the French, and was convinced that these two Powers would prefer a Turkish prince to a German one. He thus knew it would be difficult to win over Entente support for Albania.

Ismail Qemali maintained a neutral stance between Austria-Hungary and Italy, but Austria-Hungary wanted more from him and put him under pressure. With the help of an officer he trusted, Qemali sent a confidential letter to the British Admiral Cecil Byrnes, head of the inter-allied commission in Shkodra, apparently to get instructions from London because he had always enjoyed British support. However, the officer in question was curious and opened the letter. When he read its contents, he was enraged because all Albanians nationalists of the period were solidly pro-Austrian. Austria, in its own interests, was keen to play its trump card for the establishment of an independent Albania. Accordingly, the officer handed the letter over to the Austro-Hungarian authorities in Shkodra. From that moment on, Austria lost all confidence in Ismail Qemali. Its confidence was sapped all the more by Faik Konitza, Dervish Hima and other pro-Austrian figures, and Austria-Hungary thus decided to throw its support behind Essad Toptani.

With the exception of the well-known patriots Preng Pasha, Aqif Pasha, Abdi bey Toptani and the Kosovar chiefs, all the leaders of Albania, including Faik Konitza, Mid’hat Frashëri, Mehdi Frashëri, Dervish Hima, Abdyl Ypi and Nexhat Libohova, turned against Ismail Qemali. Their opposition stemmed from personal differences and ambitions, not to mention from a few mistakes made by Qemali.

In view of Ismail Qemali’s involvement in an agreement with the people of the Pindus region to alter the southern border as it had been envisaged at the Ambassadors’ Conference, and of his involvement in the Grebena affair in support of a Turkish prince, the Control Commission advised Qemali to resign as head of the government. He did so immediately and left Albania.

Fighting in Dibra after the Balkan War. The Serbian Invasion of 1912

The bust of Dibran warrior Elez Isufi (1861-1924) in Peshkopia

(Photo: Robert Elsie, October 2013).

With the defeat of the Turkish army in 1912, the men of Dibra were divided into three camps:

1. One camp, headed by Selman Alia and Llan Kaloshi, set off to defend the barracks in Shkodra from the Serbs and Montenegrins. The barracks were then under the command of Hasan Riza Pasha and later of Essad Toptani.

2. Another camp, headed by Elez Isufi and Shaban Lusha etc., deployed to Kolosjan near Bicaj to stop the Serbian advance from Kosovo. Elez Isufi had some artillery at his disposal, i.e. two cannons. After intense fighting, Isufi became the subject of a folksong that is sung to this very day:

Krisi pushka, gjimoi toka,

Vjen Elezi me dy topa.

Krisi topa, gjimoi kepi,

Kujtoi Serbi se asht mbreti.

Nukë asht mbreti, more Serbi,

Asht Elezi me malësiRifles fired, the land resounded,

Here comes Elez with two cannons.

Cannons fired, the capes resounded,

The Serbs, they thought it was the Sultan.

No, Serbs, it was not the Sultan,

It’s Elez’s highland fighters.3. While the fighting was going on in Luma, other Serbian forces reached the highlands of Greater Dibra through Macedonia where the encountered Dibran forces under the command of the leaders of Upper Dibra. In this fighting, the Serbs made use of a local Macedonian wholesale trader called Todo Bojaxhiu to convince the Albanian leaders that the Serbs would not occupy Albanian territory, except the town of Greater Dibra which was of strategic interest to them. As such, Dibran forces agreed to withdraw and go back to their places of origin, and the Serbs entered the town.

However, the cunning Serbs did not keep their promise. They subsequently sent military forces into various key regions of Dibra and endeavoured to capture Elez Isufi. Isufi, however, managed to escape the siege in a very courageous and curious manner.

Aside from this, another Serbian force crossed over the Topojan Bridge and entered the Highlands of the Small Gorge (Malësia e Grykës së Vogël). Shot were first fired at the shepherds in the village of Mazhica, and fighting with the enemy began. Before that, the population of the Greater Highlands (Malësia e Madhe), the Small Gorge, the Large Gorge, Bulqiza and Golloborda was called together by the elderly patriot Mersin Dema to a meeting at the cemetery of Shupenza. This was known as the Assembly of the Nation (Kuvendi i Atdheut) where allegiance was sworn to fight the Serbian army. A few days after the formation of this alliance, the Serbs crossed the Drin River into the Small Gorge region, to the villages of Topojan and Mazhica in order to occupy all the territory of Dibra. Here, true to the allegiance they had sworn, the whole population, including the men of the Peshkopia Mountains, rose against the Serbian army and began fighting in Mazhica and Topojan. The Serbs were defeated and withdrew across the Drin to the village of Vojnik in the area of Maqellara where the commander of the Serbian army, General Ferdinand, died. Mersin Dema then divided his forces into three parts: one for the Topojan Bridge, one for the hills around the village of Gjorica, and one for the Spileja Bridge.

Fighting carried on for three weeks in this region. Realising that they could not break through the front here, the Serbs then took another direction through the mountains of Struga and Golloborda and overcame Dibran forces who withdrew and took up new positions around the Murriza Pass (near the village of Bllac) and on the cliff overlooking the village of Gjuras where fighting raged for five days. Many of the men of Dibra, including Hysen Dema, were killed at this time.Overwhelmed by Serbian forces, the Albanians withdrew to the Mat region. Reorganised and reinforced by the men of Mat, they took up position for a third time at the Murra Pass and the Buffalo Pass (Qafa e Buallit). Here the fighting went on for some time and the Serbs were unable to advance. This episode was known as the Battle of the Highlands (Lufta e Malsisë).

The rest of Dibran forces prepared for a general uprising against the enemy by deploying their men in Shumbat, Peshkopia and at the Lusha Bridge. Some of the men reached Lower Dibra in a round-about way.The Battle of Vllajnica

The uprising against the enemy was about to break out anytime. The Dibran leaders had decided to rise, though without a specific date in mind, but the population, inspired by patriotic sentiment, opened the battle of Lusha Bridge on 15 August 1913 quite spontaneously. At the same time, fighting broke out in Shumbat, too, where the enemy was sorely defeated. Most of the soldiers were slain, the rest were taken prisoner and, as such, there were no soldiers to return to Peshkopia were their forces were concentrated. Dibran forces then marched on Peshkopia from where the enemy was shelling constantly with its artillery. When the men of Dibra reached the Pilaf Cemetery, under a hail of machine-gun fire, a highlander who was called Mehmet Skepi, a fellow with a long moustache, shouted to his comrades, saying: “Anyone who perishes today will live forever!” and called upon them to take the enemy alive. The men set off on the attack and got to the outskirts of the town. It was here that Aziz Lusha was gravely wounded. When his comrade tried to remove him, he said: “Let me die here, for this is the sweetest of deaths facing the enemy.” Having said this, he passed away.

When enemy forces were driven out of the military barracks, they withdrew to the outskirts of the town. In one street, a highlander called Ibrahim Peci came across a company of soldiers and killed four of them, but was severely wounded himself. When his comrades went to get him, he told them not to bother about him but to advance further and kill the remaining soldiers. These are but a few examples of the heroism of the men of Dibra in the fight to defend their country against enemy forces.

Hearing the echo of artillery in Lower Dibra, the men of Upper Dibra began to gather before their leaders in the various villages to decide what to do, since their fellow Dibrans were at war. Decisions were taken at assemblies in Maqellara, Kërçisht, Homesh and Sepetova. A fellow called Karaman Popinara from the village of Popinara, who had a long shock of hair and carried a Martini rifle, took 20-30 of his men and hastened to Kërçisht where 3,000-4,000 fighters had gathered. After greeting everyone, he went up to Maliq Kërçishti and said: “What are we waiting for? Lead us onwards for there is no time to lose.” He was told that they were waiting because they had not heard any news from Lower Dibra as to whether the fighting had actually begun. Karaman replied, saying: “Fighting has already begun because in our village we can hear the artillery being fired at Peshkopia,” and appealed to the leaders: “Get up, men. Don’t sit around any longer. Let’s march on the enemy and with God’s help we will not stop until we get to Belgrade!” Inspired by him, fighters marched on the town of Dibra from all directions. The first encounter occurred in the village of Krifca near Dibra, and there was a major clash with the vanguard of a Serbian regiment equipped with machine guns and light artillery, but it was overcome. The town was attacked from the west by the men of the Small Gorge Mountains and Golloborda. After fierce fighting, the town of Dibra was taken and remaining enemy forces withdrew to Reka in the direction of Gostivar.

Enemy forces in Peshkopia were wiped out by the highlanders of Lower Dibra who advanced without stopping on Greater Dibra to help their brethren at battle with the same enemy.

The men of Dibra, all united, pursued the enemy towards Gostivar. The enemy had deployed major forces in Vllajnica and Mavrova because these places were favourable for defence.

There the fighting continued for 20 days. The heroism of the men of Dibra was indescribable. Many gave up their lives to defend their villages. The heroism and personal sacrifice of many men has not been forgotten. A song was made about the fighting there and is still sung by the mountain people today. Here are a few lines:

Ditën e dielë, ditë pazari,

Emër bani komandari,

Komandari, i bir Shkinës,

S’i ke njoftun djemt’ e Dibrës,

Djemt’ e Dibrës, djemt’ e malit,

Që ta plasin kapakn’e ballit.It was market day, a Sunday,

Rose to fame here, a commander,

This commander, Slav his mother,

Didn’t know the lads of Dibra,

Lads of Dibra, of the mountains,

Shot the cap right off his forehead.But the enemy brought in reinforcements and attacked again. Dibran forces counterattacked to shore up their positions. It was there that the fighter Emin Beg Çela of Dohoshisht was slain. After two days of bloody fighting, Dibran forces were obliged to withdraw from the front when they realized they were surrounded by an enemy division coming down the Drin Valley from Monastir [Bitola] and Struga to attack them from the rear. They took their women and children with them and fled to the other side of the Drin as quickly as possible. Enemy forces were harassed the whole time by the rear guards of our men. At Mount Skertec, the men of Dibra put up much resistance to prevent the advance of the enemy, and Xhetan Kaloshi and Xheladin Shehu were killed here.

As a consequence, the whole region of Dibra was emptied of its population, with the people fleeing towards Elbasan and Tirana. Finding the region deserted, the enemy pillaged everything they could find and set fire to all of Dibra. Dibra burned for the second time.

Janina Surrenders to the Greek Army

When the Vlora government was formed, Ismail Qemali called on all Albanian officers and patriots on the various fronts of the Balkan War to withdraw from the fighting and return home.

Mid’hat Frashëri was opposed to this and went twice from Vlora to Janina to encourage Albanian reservists to continue fighting to the end. He was convinced that the longer Janina was held by the Turks, the more chance there was for Chameria to remain part of Albania. Qemali had given up hope of this. This was one of the reasons for the hostility between Frashëri and Qemali. Frashëri later admitted that Qemali had been right. Janina resisted until 6 March 1913 and then surrendered to the Greek army.

The Surrender of Shkodra

The battle for Shkodra continued to rage between the Turkish army and Albanian volunteers under the commander of Hasan Riza Pasha and later of Essad Pasha Toptani on the one hand, and the Montenegrin army on the other. Some of the highlanders of the Malësia e Madhe who had been forced to emigrate to Montenegro during the uprising of 1911 had joined forces with Montenegro and were fighting against the Turkish army.

Essad Pasha Toptani (1863-1920) at his villa in Rreth near Tirana

(Photo: Auguste Léon, 17 October 1913).The commander of the Turkish army, Hasan Riza Pasha, an excellent figure in the Turkish general staff, was a good officer and a man of fine qualities. During the siege of Shkodra, the Archbishop of Shkodra, Monsignor Jak Serreqi, and the Abbot of Mirdita secretly sent Mark Onbashi to Vlora to meet Ismail Qemali such that the two parts of the country were in continuous contact during the fighting.While the fighting was going on in Shkodra, the Ambassadors’ Conference in London was discussing Albania’s northern border. Alush Lohja, a personal friend of Hasan Riza Pasha, said one day to Captain Xhemil Prizreni, the Pasha’s aide-de-camp: “Please convey the following to Hasan Riza Pasha because I don’t dare say this to him myself. Since Turkey has lost the war, it is meaningless to fight any longer under the Turkish flag in Shkodra.” When Hasan Riza learned what Alush Lohja had said, he went to his house with two Young Turkish officers, one of them the commander of Tarabosh and the other the commander of Bërdica, and said to Alush Lohja on his doorstep: “I regret that we have only been in contact through an intermediary because we are friends.” In the presence of the two officers, Alush repeated what he had said. The officers made no comment. Hasan Riza had taken them with him so that they could hear with their own ears what the population was saying about the battle of Shkodra.

That same day, Hasan Riza and Alush Lohja went to meet Jak Serreqi, the Archbishop of Shkodra, to convey two letters to the highland tribes that were collaborating with the Montenegrin army. A further letter was sent by the Catholic clergy to their supporters, calling upon them to defend Shkodra under the Albanian flag. The letters were despatched. On that same day, the Young Turkish General Staff took the decision to eliminate Hasan Riza. They communicated their decision to Essad Pasha, commander of the reservists, and proposed that, after Hasan Riza’s death, Essad should be made commander in his place. Hasan Riza was invited that night to the house of Essad Pasha to discuss the military situation and, when he left to return home, he was shot and badly wounded.

Qani Korça, a policeman who worked for Essad Pasha, went immediately to the house of Alush Lohja and told him what had occurred. When Alush got to Hasan Riza Pasha’s house, he found him dying. His last words were: “I would like to have taken these two decorations (bullets) to the front with me and not leave them here, but since I am dying, I call upon the young men of this country to take revenge for me.” Hasan Riza Pasha, whose aim was to save Shkodra and who fought under the Albanian flag, died at the hands of the Young Turks who were sworn enemies of Albanian independence. The murder took place with the approval and participation of Essad Pasha Toptani, on 3 January 1913.

Following the death of Hasan Riza, Alush went to the funeral ceremony where he came upon Essad Pasha and the two above-mentioned Young Turkish commanders as well as other Young Turkish officers. After exchanging a few words, Essad said to Alush: “You are the best man to find the murderer of Hasan Riza. I have the impression that the crime was committed by Ndoc Deda of Shoshi, incited by Montenegro.”

Alush replied: “My opinion is that revenge for the crime must be taken upon someone in this room.”

Essad then retorted: “I shall be your friend for as long as I am in Shkodra.”

Alush responded: “According to tradition, such an offer of friendship must be accompanied by a visit to my home.” Therefore, the next day, Essad Pasha went to the house of Alush Lohja and won him over. Alush was the cleverest and most courageous man in Shkodra and later played an important role in the Shkodra region in carrying out Essad’s diabolical plans.

On 12 April 1913, after a month of negotiations, Shkodra and its majestic fortress surrendered to the Montenegrin army, on condition that the men in the fortress could withdraw and take all their arms with them.

This took place at a time when the Ambassadors’ Conference in London was considering giving to Albania not only Shkodra but also Gjakova. But after the surrender of Shkodra, Austria-Hungary’s diplomatic hand was weakened and they were faced with the dilemma of giving Albania either Shkodra or Gjakova. Of course they chose Shkodra.

Essad Pasha Moves on Tirana

After handing Shkodra over to the Montenegrin army on the basis of an agreement that was later published in Shkodra in the 1918 Calendar, Essad Pasha went to Tirana with an army consisting of Turks and Albanians. In accordance with the agreement, this army was welcomed with honours by the Serbian army in Lezha. When he reached Tirana, Essad left the Albanian soldiers their weapons, telling them to keep them in their homes so that they would be ready for use whenever needed.

The Turkish soldiers in Tirana left for Durrës and boarded a Turkish steamship to return to Turkey.

Essad then continued on to Vlora where he was appointed minister of public works in the Cabinet of Ismail Qemali. A few days later, he returned to Tirana where he brought together the leaders of the region and of central Albania, including Ahmet Zogu, Elez Isufi, Dinë Hoxha, Mersin, Dinë and Shaqir Dema, Selim Noka and Dervish Biçaku. Among them, Essad showed particular respect for Ahmet Zogu who was now 18 and increasingly influential, both because Zogu had taken part in the battle of Shkodra and because he had saved the Mat region from occupation by the Serbian army during the Balkan War (in fact, Zogu and his men from Mat wanted to take part in the battle of Shkodra but they were ambushed by Montenegrin troops in Kakarriq and dispersed).

Ahmet Zogu was a welcome guest at the home of Essad Pasha.

When the representatives all gathered, Essad Pasha greeted them and said: “As you will have heard, the Great Powers have recognised the independence of Albania. In such a fortunate situation, each of us must now consider how the country is to be ruled and who is to rule it. For my part, I believe that since Albania has a Muslim majority, its ruler should be a Muslim. I am sure that you will agree with me on this.” When he finished speaking (in the home of Selim Pasha Toptani), he departed without giving anyone else a chance to respond. Thus, since no one openly opposed his view, it was taken as accepted by everyone, with the exception of Ahmet Zogu. When Essad left for Durrës to set up a government for central Albania, Zogu sent a telegram to Osman Bali, pretending that it had been written by Essad. Osman Pasha was the commander of Essad’s men in Tirana at that time. The telegram urged him to give Zogu arms and ammunition which the forces he had brought with him needed.

Essad was furious when he heard about this treacherous trick, but as he was busy with the formation of the government for central Albania, he had no time to act against Zogu.

Abdi, Murat and Refit Toptani were all against the views and doings of Essad Pasha.

Taking advantage of Essad’s preoccupations in Durrës, Ahmet Zogu surrounded the Mat region and defended it until Prince Wied arrived. Mat was thus virtually independent at the time of Essad Pasha’s administration.

* * *

On 18 September 1913, Essad returned dissatisfied from Vlora and sent the cousin of Abaz Kupi to Lezha to take a letter to Mano beg Lezha to initiate contact with Preng Pasha in Kallmet. In his letter to Preng Pasha, Essad said: “I have come to work in Durrës as minister of the interior. Let us work together. I would at least ask you to support me because Prince Wied has been appointed as our monarch and there is nothing we can do about this.” Essad asked Preng Pasha to send his messenger to Shkodra because he had more letters to distribute. There were four letters for Shkodra: to Myfti Adem Efendi, Alush Lohja, Sulçe Begu and Muharrem Kazazi.

Ibrahim Kumanova, who was Preng Pasha’s secretary, opened one of the letters and read the following: “I have come to work in Durrës as minister of the interior because I cannot work with Ismail Qemali. Why don’t you come, and we’ll talk about finding a Turkish prince for the country.” When Preng Pasha saw the difference in the contents of the letters, he was shocked, as were Musa Shehu (of Prizren), Hysni Curri (nephew of Bajram Curri) and Dan Hasani who were with him. Bajram Curri was in Kthella at that time. Preng Pasha and his men decided to send Dan Hasani to Essad with Preng Pasha’s visiting card, on which was written: “Dan is charged with giving you my reply.” Dan reached Essad Pasha in Tirana where he was with Fadil Pasha Toptani and Dervish Hima. When Dan was alone with Essad for a moment, he handed him Preng Pasha’s visiting card and said: “I do not think it is a good idea to set up a new government in Durrës because this would give the outside world a bad impression of Albania, as if I were to set up a government in Mirdita or Gjeto Coku were to do so in Lezha. This discredits us abroad. I would invite you as minister of the Vlora government to meet me as deputy prime minister so that we can talk and discuss the situation. If we find that Ismail Qemali has faults, we can overthrow him legally.” Essad Pasha responded to Dani as follows: “I cannot work with Ismail Qemali at all so at least try to persuade Preng Pasha to remain neutral,” adding: “and ask Bajram Curri to come to Tirana. He is in Kthella at the moment. If he cannot come, let him at least come to Kruja where I can go and talk to him. And give Bajram Curri a thousand quintals of grain to feed the highland tribes of Gjakova.” With this, Dan returned to Kallmet.

Statue of Kosovar rebel leader Bajram Curri in the town of Bajram Curri in northeastern Albania

(Photo: Robert Elsie, October 2013).When Ismail Qemali left Vlora, Preng Pasha and his men decided to send a delegation consisting of Musa Prizreni and Dan Hasani to Nice in France to ask Qemali on behalf of Preng Pasha and Bajram Curri to return to Lezha and re-establish the Vlora government now that Shkodra was under occupation by international troops, and thus counteract the doings of Essad Pasha. Ismail Qemali replied: “My sons, Albania will be drenched in blood. We must avoid the blood-letting. Embrace Preng Pasha and Bajram Curri for me.”

* * *

Essad Pasha formed his government of Central Albania on 14 October 1913 with Ali bey Zajmi (of Dibra), Isuf bey Dibra and Aziz Vrioni, and its administration was stable. With the new government formed, the International Control Commission asked Essad to form a delegation including all the leaders of the country to go to Germany and offer the Albanian throne to Prince Wied. Essad accepted on the following two conditions: 1) that Durrës be the capital city; and 2) that he be given the posts of minister of the interior and minister of war in the coming cabinet. The Control Commission accepted and the delegation of Albanian leaders set off for Germany to offer Prince Wied the throne. The latter arrived in Durrës as the country’s new monarch on 7 March 1914.

The Formation of Prince Wied’s Cabinet and the Plots of Essad Pasha Toptani

Prince Wied charged Turhan Pasha with the formation of the cabinet. He had been recommended by the Tsar of Russia since he had been Turkish Ambassador in Saint Petersburg for 25 years. He won over the Palace because he was a good speaker and knew several foreign languages.

Essad Pasha was made minister of the interior and minister of war, and Preng Pasha became deputy prime minister.

After his arrival, Prince Wied visited Tirana and was ceremoniously received there. However, rumours spread here and there at the time that Wied was acting to the detriment of the Muslim faith and had, for instance, given his officers caps in the form of a chapel.

In March, a few days after his visit to Tirana, rumours spread that Greek Andartes had begun moving towards the Albanian border. Several days later, these rumours were confirmed.

For this reason, Prince Wied returned to Tirana and assembled the population in front of the Scanderbeg Barracks. He informed them of the Greek invasion and told them to: “take arms and fight the enemy for the sake of the nation.”

Before going to Tirana, Essad Pasha went to Vora where he met Man Picari, Myrto and Dervish bey Arbana and others, to whom he said: “My view is that, although Wied was chosen by the Great Powers, he remains a foreigner and does not know our customs. Especially, he is not a Muslim whereas most of the people are and, recently, he has not been respectful of our faith. For instance, you will notice that he has put that cap on the officers. For these reasons, I think that something ought to be done to get rid of him and replace him with a Muslim.” The rest of them agreed and gave him their word, saying: “We are ready to carry out your orders at any time.” Having come to an agreement, Essad said: “I am going to Tirana to tell the people to take to arms to fight the Greeks who, as you know, have attacked our southern border, but when they set off for the border and pass through here, you must stop them, even if you have to use your weapons to do so, and tell them you will not let them pass because you are going to rise against Wied.”

When the force of nationalist volunteers of some 500 men led by Refik Toptani, Musa Beqiri (Musa Qazimi, the mufti of Tirana), Sheikh Musa Dushku and others, all from Tirana, reached the Limuth Bridge at Vora, they encountered the rebels under Man Picari and his cohorts who were waiting for the volunteers and stopped them. A small skirmish occurred between them, and the volunteers were forced to return home on 6 May 1914.

The Greek invasion began and there was fierce fighting between the two sides. Essad did whatever he could to urge the ignorant peasants to rise against Prince Wied and most of the ammunition reserved for the fighters going to war with the Greeks was distributed instead among Essad’s followers.

Essad also sabotaged the structure of the army to be sent south to fight the Greeks. Only one battalion of reservists was sent to Korça. It was under the command of Major Ali Fehmi Kosturi.

The Situation in Shkodra

During the Balkan War, the Muslims of Shkodra fought for seven months side by side with the Turkish army. The volunteer forces of Dibra also took part in the war and fought heroically against Serbian forces at the battle of Bërdica.

The Catholic mountains tribes of Malësia e Madhe who had taken part in the uprising against Turkey in 1911 erroneously supported the Montenegrin army.

Hasan Riza Pasha was killed after the agreement had been made to defend Shkodra under the Albanian flag. Essad Pasha handed Shkodra over to the Montenegrin army which was shortly afterwards obliged to surrender to international naval forces. Later, Shkodra was handed over to international land forces, except for Russia, and was placed under the command of the British Colonel Phillips.

The international forces set up an administration with Albanian functionaries. Essad Pasha and his supporters, including Alush Lohja, still endeavoured to get Shkodra under their control. He had sufficient funds given to him by France, that was promoting Slavic influence over Austrian. At this time, the Bashkimi Club was formed in Shkodra, consisting of 12 members, six Catholics and six Muslims, including well-known nationalists of the period.

In February 1914, the highland tribes assembled in Shkodra, including groups that were both for and against Essad Pasha. The Abbot of Mirdita also took part.

The first person to speak at the meeting and explain the reason it was being held was Nikollë Mirashi, an Essad-supporter from Kastrati, who said: “Since Essad is an Albanian and a brother of ours, as Ismail Qemali is, we will all support him.”

Ded Gjo’ Lule replied: “That is not true, you are a Montenegrin.”

“If I am a Montenegrin, you are an Austrian a hundred times over,” replied Nikollë Mirashi. Ded Gjo’ Lule seized his rifle, but the abbot intervened and prevented a massacre. The meeting then broke up.

After the meeting in February, Cuf Lohja (the nephew of Alush Lohja) and Nikollë Mirashi prepared to leave and join Essad with 900 highlanders. Essad retained only 50 of them. He wanted these men to join the forces of central Albania, to overthrow Prince Wied and to make him the new head of state. Both Lohja and Marashi were agents of Essad, but Lohja was also commander of the volunteer forces. When Essad went to Germany to pay homage to Prince Wied, the highlanders returned to Shkodra to await his orders.

When he returned from Germany, Essad Pasha called Cuf Lohja and Nikollë Marashi to his estate at Lapraka near Tirana and asked them to assemble 2,000 highlanders within three days. While they were getting this force ready, rumour spread that Prince Wied had attacked and shelled Essad, who had now gone abroad. Colonel Phillips summoned Lohja and Marashi and told them to place the men who were going to join Essad under the command of Preng Pasha to help Prince Wied, but they refused to do so.

Essad Pasha set off for Naples and Paris where he conducted talks with the French government and later went to Athens and Nish. From Nish, he sent a letter to Alush Lohja in Shkodra by means of Selim Xhija of Peqin in which he urged Shkodra to join the ehli kijam (rebel folk) against Prince Wied.

The red and black flag of Albania still flew on the fortress of Shkodra. Both Muslims and Catholics had agreed on this, although the Muslims still refused to accept a flag with an eagle on it, despite the fatwa issued by Haxhi Vehbi Dibra, the mufti of Vlora. The Catholics supported Wied and Austrian policies whereas the Muslims, under the influence of Essad, preferred to have a Muslim prince. Later, when Essad went to Germany to pay homage to Prince Wied, all of the Muslims, except Alush Lohja, turned against him.

* * *

Under the international administration in Shkodra, relations between the Catholics and the Muslims were the worst that they had been since the time of the Turkish Constitution. The animosity between the two religious communities was worse there than anywhere in Albania because the Catholic majority in the Prefecture of Shkodra was under the rule of a Muslim minority that constituted the majority in the town itself. The Muslims, favoured by the Turkish government, had played a more active role in the administration of the country. Their rule extended into the mountains with a Kir Serdari [local Turkish commander] and a primitive code called the Kanun of the Mountains (Kanuni Xhibala). The Muslims here, as in other parts of Albania, considered themselves to be more competent to rule the country than the Catholics because they were used to working as public officials and possessed land, whereas the Catholics were hand-workers and merchants. Since they had been more involved in administration and in settling conflicts outside the town, the Muslims had long gained a certain expertise in administrative matters.

With the political and financial support of Austria-Hungary, the Catholics established the Jesuit Saverian College as well as elementary schools run by the Franciscans and an order of nuns. In this way, they contributed to the promotion of Albanian as the national language.

The animosity that arose from time to time between the two communities was caused more than anything by erroneous interpretations of events that had taken place and by extremist words and deeds of individuals incited by fanatics or foreign interests. The community to which a person belonged was unjustly accused of being the guilty party. What is more, a new situation was created with the collapse of Turkish rule and the installation of the international regime and of a more modern administration. The Catholics were more prepared to use Albanian as the official language and were therefore favoured for public service positions whereas the old Muslim employees who did not have these skills were gradually removed. The Muslim side was offended by these changes.

The vast majority of Muslims had been for a Muslim prince whom they considered would serve as a guarantee for the continued predominance of their religion.

Various newspapers began to be published in Shkodra under the international administration. Among them was Sadai milet (The Voice of the People) that was printed in Turkish. It openly supported the idea of a Muslim prince. The newspaper was managed by a board of six leading figures, among whom Musa Juka and Ymer Luftia were the most active.

New and old conflicts between the two communities led to anarchy in Shkodra. Both Essad Pasha and the Young Turks were working actively to transform the situation as they, respectively, wanted to have it. The Muslims, however, came to realise that the Young Turk idea of a “union between Albania and Turkey” was impossible. Adem Efendi, the mufti of Shkodra, replied to Beqir Grebena as follows: “We could not deal with Turkey while it was here and we do not want to return to the past. Such an attitude would be bad for us in world opinion.”

The Catholics, under Monsignor Serreqi, the Archbishop of Shkodra, were the first to go to Durrës and swear allegiance to Prince Wied. Later, the Muslims held a meeting at the Plaka Mosque to discuss the matter from religious and national perspectives, and most of them agreed to recognise Wied as the monarch of Albania. They elected a delegation of 18 men to go to Durrës on their behalf and swear allegiance.

Xhemal Naipi, the kadi of Shkodra, took a letter of recommendation from Colonel Phillips with him to Prince Wied, asking him to receive the delegation in a personal audience, but without Essad Pasha. The delegation was received on a day in March 1914 at two o’clock in the afternoon and Shkodra thus recognised Wied.

The Revolt of the People of Central Albania against Wied (1914-1915)

Having urged the people of central Albania to rise against Wied so as to become head of state, Essad Pasha was himself forced to leave Albania. Kavaja was the first place to raise the Turkish flag. The government decided to second an expeditionary force against the town on 23 May 1914, made up of a company of gendarmes and volunteers from among the mountain tribes of Shkodra who had arrived in Durrës to defend Wied. At the moment this force was to depart for Kavaja, Murat and Tefik Toptani arrived in haste from Tirana begging for assistance and telling alarming tales of the situation there. The government thus changed its plan and seconded a company of gendarmes, headed by the Dutch Captain Jan Sar and Lieutenant Bajram Fevziu, and consisting of highland volunteers and about 20-30 nationalist volunteers under Reuf Fico, the deputy prefect of Tirana.

Albania’s imposed monarch, Prince Wilhelm zu Wied,

at the konak (royal palace) in Durrës, 1914.This armed force departed after midnight and stopped over in Shijak. When they were about to set off for Tirana in the morning, the highland volunteers, who had been won over by the people of Shijak in the night, refused to go, saying: “We came to defend Wied and not to fight,” and they returned to Durrës. Captain Xhavit Leskoviku informed Captain Sar that they would all have to go back to Durrës because they could not continue on to Tirana with such a small force. Sar insisted that they carry on, but sent an urgent telegram to his commander in Durrës. Unfortunately, the telegram fell into the hands of General De Veer and not of Colonel Thomson who had issued the marching order in the first place.The force continued its march but fighting broke out when it reached a hill to the left of Shijak and in no time at all, everyone was shooting. Government forces withdrew to the hill on the right side of the road and were forced to return to Shijak where most of the gendarmes took refuge in a government office made of mud and others in a school building. Fighting began here, too, and some of the gendarmes were killed by bullets that went right through the mud walls of the office building.

Captain Xhavit Leskoviku of the general staff advised Captain Sar to withdraw, abandon Shijak, and take up position in Rrashbull to avoid being surrounded. But Sar, who did not know the countryside and the customs of the people, would not listen to him. As such, government forces were surrounded and forced to surrender, but the men of Shijak later came to regret what they had done and, to shirk any possible responsibility, claimed that government forces had broken the ceasefire. Captain Leskoviku announced: “Whatever the case may be, we will ask Wied to issue an amnesty decree and the matter will be brought to an end.”

Sar departed for Durrës and got the decree but, unfortunately, when he got back, he found that the rebels of Shijak had taken Rrashbull before the national volunteers, of whom I was a member myself, could get there. The commander of this volunteer force of 50-60 men was Captain Meleq Frashëri who advised General De Weer, telling him that Rrashbull could not be taken with such a small force of men lacking proper military training. The Dutch general, who was not up to the task with which he had been entrusted, rejected the advice and ordered them to attack on 23 May 1914. Meleq got on his horse and set off with the volunteers on the attack along both sides of the road. There, Meleq was wounded and 13 of the volunteers were killed, including Ceno Sharra and Haki Glina. Some of the volunteers were taken prisoner and others withdrew to Durrës.

With the complete defeat of the volunteers, the Durrës road was in the hands of the rebels. People in Durrës were in panic and expected the rebels to arrive any time. Wied, his government and most of the high-ranking figures in the town took flight onto a steamship.

Wied then sent Mehmet Pasha Dërralla with a white flag to seek a ceasefire with the rebels. The fighting had subsided by this time, but the rebels were undecided and did not know how to take advantage of their unexpected victory. Some of the Kavaja rebels now made their way to Shijak and caused the ceasefire to break down. As such, the prisoners of war could not be released. Captain Sar addressed the rebels and, at the end of his speech, he called out: “Long live Albania!” To this the rebels replied: “Long live the Father of the Nation” (Rroftë Baba Dovleti)!” meaning the Sultan.

The International Control Commission later arrived in Shijak and Consul General August Kral, the Austrian delegate, addressed the rebels in Albanian, saying: “The Father you are calling for was not expelled by the Albanians, but by your enemies, the Greeks and Serbs, in war. He was forced to flee from Albania. What you are doing is nonsense. Stop it right now. Otherwise the Serbs will come and slaughter you all!”

The prisoners were released. Captain Xhavit Leskoviku informed Colonel Thomson of what had really taken place and Thomson rescinded De Weer’s order to send troops to Tirana. The Albanian government then asked Wied to choose one of the two men to be commander. The government decided on Thomson and informed the Dutch government accordingly, which called De Weer back to Holland.

Thomson and Xhavit Leskoviku now prepared a defence line because they were convinced that the rebels would still attack Durrës. This line went from the Weir Bridge (Ura e Dajlanit) to Cape Palla and was constantly patrolled by gendarmes and volunteers.

On 23 May, Tirana fell to the rebels.

At dawn on 15 June, the rebels attacked Durrës from Cape Palla with 500-600 men of Shijak and from the Weir Bridge with men from Kavaja under the command of Sheh Hamdiu of Shijak. Government forces withstood heroically, indeed both sides fought heroically, and the rebels were defeated, with many of them killed. Their commander, Sheh Hamdiu was wounded and was offered treatment in hospital in Durrës. The veteran patriot, Captain Kamber Sejdini, who was one of the most distinguished officers in Albania at the time, was slain in the fighting in the hills.

Colonel Thomson was directing operations in Gazhana with several of the leaders of the volunteer force. A fellow from Kavaja snuck secretly in by sea from the direction of the Weir Bridge and got close to Gazhana. He then hid in a bush from which he shot and killed Colonel Thomson. He also shot and killed Ajdin Draga, the brother of Nexhip Draga. Neither of them even realised where the bullets had come from. But a gendarme from Kurvelesh caught sight of the fellow from Kavaja and, in an exchange of fire, the Kavaja man was shot and killed.

The killing of Colonel Thomson caused a great reaction in Durrës and had an almost decisive effect on the course of events.

The central Albanian uprising was, in fact, a plot organised by the foreign and domestic enemies of Albania to destabilise the Albanian administration created by the Great Powers at the Conference of London, with Prince Wied as the country’s monarch, and to create conditions more favourable to them, according to the objectives each of them had.

The domestic enemies were: (a) Essad Pasha Toptani and his followers whose aim was to expel Wied, overthrow the government, and take power himself; (b) the Turkophiles such as Musa Qazimi, the mufti of Tirana, and Qamil Haxhi Feza of Elbasan who wanted central Albania to be closely allied with Turkey and, if this should prove impossible, then at least to elect Burhanedin, the son of Sultan Hamid, as Albania’s monarch.

Essad Pasha initially allied himself with the Turkophiles to ensure their co-operation in overthrowing the government.

The foreign enemies were the Young Turks, France, Italy, Greece, Serbia and Montenegro. All of them gave effective support to Essad Pasha and the Turkophiles in order to partition Albania. Most of the rebels, radicalised by Essadist and Turkophile propaganda, wanted to expel Wied and return to the Sultan […].

The uprising against Wied began at a moment that was beneficial to the country’s enemies, i.e. when the people of southern Albania were in a live-and-death struggle with Greece to defend their country against invasion, against the autonomy of Northern Epirus and against its government headed by Giorgios Zographos of Qestorat. The prime minister of Serbia, Pašić, also played a role in these criminal dealings to set up a Zographos-type government in Dibra, headed by Arif Hiqmeti of Kumanovo.

In May 1914, Musa Qazimi and Qamil Haxhi Feza set up the Kruja Alliance (Besëlidhja e Krujës) where they resolved to fight Wied and unite Albania with Turkey under Sultan Burhanedin. In early June, the ehli kijam took Kruja and Kavaja. In the towns and villages where they had power, the rebels formed local councils to further and lead the uprising.

On 3 June, before taking all of central Albania, the councils held an assembly in Shijak at which a first General Council was elected with the following figures: president Mustafa Ndroqi (an Essadist), vice-president Xhenabi Adili (a Young Turk), a Turkish army major, and Qamil Haxhi Feza, a Turkophile from Elbasan as their general commander. This coalition shows that all sides were ready to compromise in order to reach their common objective, i.e. to expel Wied and overthrow the government. The uprising continued to spread. On 17 June, the government of Aziz Pasha Vrioni collapsed and Lushnja was occupied by the rebels, as had been Elbasan on 2 June. After the fall of Elbasan, Çermenika, Qukës and Mokra joined the rebel movement.

With the occupation of Elbasan, Korça was separated from Durrës and was on its own to defend the country on the Greek front. The prefecture of Korça sent a well-organised force of some 400 volunteers from Kolonja, under the command of Izet Zavalani, to open up the road and ensure communications with Durrës. Although they were advised by the patriots of Pogradec not to begin fighting in the Pleçisht hills near Mokra because the zone had joined the rebels, they attacked the fighters of Osman Çota, who were much more numerous. There was fierce fighting. Ibrahim Baçi of Mokra and Muharrem Udinishti took the side of the men of Kolonja who were, however, forced to withdraw, leaving about 50 men dead. Among them was the 75-year-old Zalo bey Prodani who fought a duel with Aziz Alla. Both were killed. Gani Butka was betrayed and died after he was shot and wounded by a bullet fired from a window in Pogradec. Et’hem bey Starova also opposed the volunteer force.

When the rebels entered Pogradec, they went as far as the Maliq Bridge, where they stopped because they regarded it as the border between Albania and Greece.

Faced with the increasing victories of the rebels, Wied and the members of his government were alarmed and began to knock on every door to find volunteers to quash the rebellion. They began with the high-ranking families who were Wied’s powerbase.

After the failure of the rebels to take Durrës on 15 June, the government began to take command of these volunteer forces as it still had sufficient funds. Accordingly, 1,200 Mirdita volunteers arrived in Durrës under the leadership of Marka Gjoni. Preng Pasha, leading an armed force from Shkodra and the highlands, took Ishëm. Ahmet Zogu and his men from Mat approached Kruja. Aziz Pasha Vrioni and his volunteers from Berat, Vlora and Mallakastra advanced on Lushnja to break the siege of Durrës by the ehli kijam. Bajram Curri sent his Kosovo highlanders to Durrës by sea.

The military authorities wanted to divide both the Mirdita volunteers and the other forces into detachments, with each one being accompanied by ten gendarmes. But Marka Gjoni refused and attacked Rrashbull without any advanced preparations. The rebels who had arrived near Rrashbull and were hiding in Shkozet opened fire on the men of Mirdita and caused great losses among them. I myself was witness to these events, from start to finish.

Preng Pasha had occupied Ishëm but when his vanguard proceeded towards Shijak, he withdrew them quickly to Lezha because he was fearful of them being encircled by rebel forces from Fushë Kruja.

Ahmet Zogu, waiting in Kruja to see how the attacks of Marka Gjoni and Preng Pasha were going, then withdrew to Mat when he heard of their losses.

On 11 June, when the rebels defeated the forces of Aziz Pasha Vrioni, they occupied Lushnja and advanced along the Devoll River.

The volunteer forces of Mallakastra and Vlora under the command of Major Besim Koka, assisted on the right by Hysni Toska and on the left by Bektash Cakrani at the Monastery of Ardenica prepared to attack Lushnja. In an attempt to reach a compromise with government forces, the head of the rebels, Arif Karbunara, a nationalist and patriot inspired by Sheh Ibrahim Karbunara, stated that he would withdraw and allow the other side to enter Lushnja.

Besim Koka was also the general commander of all the volunteer forces. Despite the gesture of Sheh Karbunara to allow him to enter the village of Karbunara without a fight, he shelled Lushnja and allowed his volunteers to plunder the town. As such, he did much to sabotage the war which he would otherwise have won. The rebels and population, furious at the bombardment, attacked government forces and forced them to withdraw under great losses. Seit Qemali was wounded here. The government forces in disarray were attacked by the oppressed peasants of Myzeqeja from their houses and gardens. They also showed their anger and fury at the large landowners and their representatives.

Bektash Cakrani stayed put and did not advance, whereas Hysni Toska fought courageously, killing many men, among whom were Riza and Godo Hekali, the sons of Rrapo Hekali.

On 12 July 1914, the rebels occupied Berat and Fier that had been shelled by Bektash Cakrani.

In Berat, the rebels executed three pro-government patriots: Captain Baki Gjebrea, Hajredin Fratari and Ismail Klosi. On 13 August, Berat was once again occupied by the men of Korça and Gjirokastra. It was in this fighting that Çerçiz Topulli took part, but on 19 August the town was retaken by the rebels who took the Vjosa and prepared to enter Vlora.

The Northern Epirus Uprising

The Conference of London charged a Dutch military mission headed by General De Weer and his deputy Colonel Thomson with setting up and organising the Albanian gendarmerie. The mission arrived in Albania and was composed of officers of various ranks. These officers, together with their Albanian counterparts, organised the gendarmerie in the free zones and foresaw for the regions still under Greek and Serbian occupation, that a battalion be set up for each prefecture. For Korça and Gjirokastra the said battalions were to be commanded by Major Mustafa Aranitasi and Major Ismail Haki Tatzati respectively. When the Greek government was forced to withdraw its occupation forces from Korça and Gjirokastra, compelled as it was by the Great Powers that had set forth Albania’s borders, the Albanian government sent in battalions with gendarmes, prefects and mayors for the various localities to take over the prefectures in question. The handover took place peacefully in Korça, Erseka, Tepelena, part of Dangëllia, Këlcyra and part of Kurvelesh.

From mid-March, the Albanian government sent 300 gendarmes under the command of Mustafa Spathara and two Dutch officers who marched from Opar to Voskopoja and Korça. The Greek army handed Korça over and departed for Bilisht and the border. But the Greeks of Korça instigated a previously planned revolt and on 2 April 1914 this uprising broke out in Korça under the Greek agent Jakovos, the despot of Durrës, and the board of the diocese of the Greek Orthodox Church. The plot was carried out by Grecophile volunteers in town and in the countryside under the command of a Captain Sulo and Greek soldiers who were in hiding in Korça and who took up strategic positions in the town.

A cry of resistance arose in all of the surrounding villages at once and Albanian patriots gathered to prepare for action. The forces of Kapo Kapedani took up position in the vineyards of Korça where the troops of Jorgji Busho, a one-time deputy for Serfije in the Ottoman parliament, were marching on the town. The villagers of Mborja in the Mborja Gorge put down the forces of Dr Harisiadi of Korça, consisting of 400 men. The town was thus liberated and the despot and the Orthodox Church administration were transferred to Elbasan.

Extremists in Korça, radicalised by the treachery of the Grecophiles there, wanted to burn the town down, but Abdyl Ypi intervened with calm resolve and saved the town from the fire.

Albanian forces penetrated Devoll, Arrëz, Nikolica and Dardha. Major Ismail Haki Tatzati set up his base in Hoçisht. Bilisht remained in the hands of the Greeks.

A stable administration was set up in Korça under the prefect Pandeli Vangjeli and his deputy Abdyl Ypi. The lawyer Kasneci of Himara became head of the court, Themistokli Gërmenji became chief of police and Hysen Nikolica was the police commissioner. The Greeks were continuing the handover peacefully but, on purpose, they did so very slowly. It was then that the plot for Northern Epirus autonomy arose. The Greek command suspended the handover of further localities on the pretext that, since the population of the villages in question had declared themselves autonomous, it had no right to impose unification and to force their submission to the Albanian government. The Greek army therefore pulled back from the borderline set forth by the Conference of London and left it to the Albanian government to deal with the autonomous Northern Epirus administration. This situation compelled the Albanian government to use force not only to liberate the remaining parts of the country but also to defend the regions that had already been handed over peacefully by the Greek army. This resulted in much bloodshed.

Once the Albanian gendarmerie had taken over Erseka, pursuant to the agreement with the Greek command for the successive handover of the areas it was occupying, the gendarmerie set off for Leskovik for the handover there. When it got close to the town, it was suddenly fired upon by the troops of the Northern Epirus government which had decided not to submit to the decision taken at the Conference of London for the reunification of the prefectures of Korça and Gjirokastra with Albania. This government demanded unification with Greece or at least some form of autonomy equal to unification with Greece. It based its claim, among other things, on the fact that the majority of the population of the two prefectures (Korça and Gjirokastra) was Christian. According to them, all Orthodox Christians were Greeks.

The Northern Epirus administration was set up, put into place and financed by the Greek government, and it was politically and militarily supported by it. The head of the Northern Epirus government was a former Greek prefect of Albanian origin from Qestorat, and the minister of the interior was a major in the Greek gendarmerie from Nivica-Bubar. He, too, was of Albanian origin.

The Albanian gendarmerie that was to take over Leskovik consisted of a company of about 120 men. Faced with the new situation and with far greater forces and arms on the other side, it was forced to withdraw with its volunteers after intense fighting, leaving 20 dead, including Qani bey Starja (also known as Qani bey Ypi, the brother of Xhafer Ypi), and numerous wounded. The volunteers had turned up as soon as they heard the rifle fire along the Gërmenj-Radom line in order to prevent the advance of Northern Epirus troops and to receive new orders pursuant to the new situation. The autonomist forces consisted of local volunteers (the Sacred Battalions) who had been recruited from the local Christian population, and who were armed and trained by the Greek government and officers of the regular Greek army. The Andartes were so-called volunteer brigades consisting of rebels from Epirus, Macedonia and Crete who had been in revolt at the time of the Ottoman Empire and were now being kept as reserve forces for any eventuality. In addition, there were units of regular Greek soldiers in the brigades of the Andartes [Greek paramilitary fighters]. They had been left in the region on purpose and were officially called deserters. They, too, were armed to the teeth.

The same thing happened with the gendarmerie of Gjirokastra. It set out from Tepelena to take over the said town and was stopped near the Han of Subashi. The gendarmerie forces destined for Përmet were also stopped outside of that town by Northern Epirus units. As such, the Albanian gendarmerie was obliged to withdraw and, once reinforced with volunteers, it took up position to defend the Han-Vjosa-Hormova-Shtepëz line.

This was the beginning of the armed conflict between the Albanians and the autonomous troops of Northern Epirus, a conflict that had tragic repercussions for the Albanian people. In the following period of fighting, the Albanians showed much self-sacrifice, courage and bravery under difficult conditions in order to unite their mutilated land and bring together the various religious communities in it.

In April 1914, the Albanian gendarmerie was reinforced with volunteer units from various parts of Albania, but in particular from the local population. They were full of enthusiasm but disorderly, undisciplined and, in particular, unequipped since they were lacking both in ammunition and in food supplies. What they lacked most, however, was a command to lead them and put them into proper order. Despite all these failings, they decided to undertake a general offensive. The aim of this offensive was to destroy the autonomy of Northern Epirus and liberate the territories still under its control.

The main goal was Gjirokastra, the seat of the Northern Epirus government, because they believed that if they took it, all open resistance would wane, and the autonomy structures would cease to exist.

The offensive began in several directions, mainly from Tepelena to Gjirokastra, but supported by a second prong from Labova to Libohova. Other prongs were Kuç-Himara, the Skërfica Pass-Delvina, Këlcyra-Përmet-Frashër-Leskovik, and Gërmenj-Leskovik. Of them all, only the Cepo Monastery-Gjirokastra and the Skërfica Pass-Delvina attained their objectives. The vanguard of the former reached the Viru [Veriga?] stream and the latter got to the Rusan neighbourhood of Delvina. Other prongs had some success, but were soon stopped in their tracks.

All in all, these initial military successes caused the autonomy forces to break up. The autonomy government began getting ready to flee. Part of the Greek-speaking population fled to Janina, Corfu and elsewhere. The Greek government was also worried by the success of the Albanians, a success that was jeopardising its project to separate Epirus from Albania. For this reason it decided to dispatch regular forces of the Janina Division to assist the autonomy government, declaring them to be deserters. These troops arrived quickly at the front and after several engagements were able to put the Albanian troops to flight. The latter, as mentioned above, consisted of a few gendarmes and a lot of bashibozuks who then took up the positions from which they had originally departed.

For some time, there was a lull in the fighting when the Albanian government embarked on negotiations with the autonomy leaders in Corfu to find a peaceful solution to the Epirus issue.

All the while, the Greeks were preparing for a new offensive to reoccupy the rest of Epirus that was in the hands of the Albanians and to reach a line stretching from Llogara to Salaria, the Kiçok Pass, Ostrovica and Maliq, if the Corfu talks were to prove a failure or if some other opportunity were to arise.

The opportunity they were waiting for soon came. The Essad uprising against Wied and against the Albanian government broke out in central Albania. It spread gradually so that rebel forces were able to occupy Berat, Elbasan, Pogradec etc., and threaten Vlora, which they occupied several days later.

The Albanian forces that were fighting the Greeks were now in dire straits. Not only were they no longer receiving support from the government, but there was a good possibility that they might be attacked from the rear by the rebels who supported Greek claims. The rebels called the nationalists infidels who had brought about the separation of Albania from the reign of the Sultan, and were fighting for reunification with Turkey.

In this new situation, the Greeks went on the offensive on all the fronts. Albanian forces, under pressure from the Greeks, and threatened and, in some places, attacked by the rebels, broke up and took flight to save their lives and those of their families. They fled in great panic to Vlora, Mallakastra and Berat.

The Greeks continued their advance, though they were slowed down here and there by Albanians who were trying to gain time to get their families out and to escape themselves, though with only the clothes on their backs. The advance was savage and was carried out with fire and sword. They burned all the property of the Muslim Albanians and slew everyone who could not get away in time, including women and children. However, it was not only the Muslims who were killed and burnt out. The Christians of Frashër and the surrounding villages, who had made common cause with their Muslim brethren, were also slain. All the farmhouses and villages that had been freed were now turned to ashes, and everything in them – farm animals and valuables – was carried off.

Of particular notoriety were the massacres in Panarit. The Muslim villagers there fled to Skrapar territory via Backa. Together with one of the agas of Panarit, who had got away with his sheep, was Stefan Panariti with his flock. Stefan later returned and the Greek authorities persuaded him to write to the aga and convince him to go back, saying that Greece now guaranteed them their lives and freedom. The aga believed him and returned, as did many people who were convinced that they had done nothing wrong. Neverthless, one night, the Greeks took all the men and slaughtered them near Grabocka and Melcka, and then they killed the women and children.

These massacres were carried out by a captain called Stratos.

An old patriot called Harri Panariti and another fellow from Treska wrote to people in America and told them about the tragedy of Panarit and a foreign committee consisting of two men subsequently came to investigate the matter.

Stefan Panariti had not written to the aga to betray him. Three Christian men of Panarit testified to this before the Greek authorities in Janina. Nonetheless, the authorities decided that the hero of the affair was, despite everything, Captain Stratos.

Because Harri Panariti had informed his friends in America, he was arrested, taken to Janina and held there for six months. He was only released after paying one thousand gold francs in cash.

Thus, the struggle to liberate the prefectures of Korça and Gjirokastra came to a temporary end. The Greeks attained their objective and took territory up to the line stretching from Llogara to Salaria, the Kiçok Pass, Ostrovica and Maliq.

The Young Turks, using their traditional principle of ‘divide and rule,’ incited Albanians of various faiths against one another in every way they could. The Orthodox were persuaded to make common cause with their co-religionists, the Greeks. The Muslims were offered jobs in public administration and, in this way, the Young Turks kept the region quiet for quite some time.

However, these initial conflicts between the Orthodox and the Muslims transformed themselves with time into violence and reciprocal hatred. A great cleft was created between them by their common enemy, but the Albanians did not realise this at the time, and it caused great damage to the nation. One repercussion was that hundreds of thousands of Orthodox Albanians lost their Albanian identity. This process is continuing today in Arbëria (i.e. among the Albanians of Greece).

The first generation of Albanian nationalists and their descendants had much work to do to overcome the divisions among them that had been created by foreign interests. The Orthodox Patriarchate in Istanbul and, later on, successive Greek governments were more active in creating division in Albania than the Turks. […]

The Military Adventures of Essad Pasha

On 18 August 1914, Essad Pasha Toptani left for Naples and Paris where he talked to the French government about the possibility of entering the war against the Central Powers. Later, he journeyed to Athens and from there, after talks with the Greek government, he carried on to Serbia. There he reached an agreement with Pšsić and Albania’s enemies, thus concluding the cycle of agreements he needed to ensure their support to carry out his plan to take power in Albania. From Serbia, he returned to Salonica where, with the help of the prefect of Dibra and correspondence, he reached an agreement with the leaders of Dibra. The part of Dibra on the western side of Drin River was under the rule of Jusuf bey Dohoçishti who had set up an autonomous government there. Having come to an accord with him and with the other leaders of Dibra, Essad Pasha entered the town of Dibra.

Jusuf bey had a force of some 3,000 volunteers under his command. Xhelal Zogu (Xhelal Zogolli) and Ceno bey Golja set out from Peshkopia to Dibra with 200 men to accompany Essad Pasha to Peshkopia. Near Maqellara on their way back, they were ambushed by a group of Albanian nationalists, but they managed to overcome them and continued on their journey.

Essad Pasha held a public meeting when he got to Peshkopia. Some of the local leaders were against him because he had come to Albania from Yugoslavia, with which they had always been at war. However, Essad paid to assemble a force of over 3,000 men, giving the leaders what they deserved, each in line with his status and position, and giving the volunteers two Napoleons each.

Essad then set off for Mat over the Murra Pass. Ahmet Zogu had refused to join him in his project, and for this reason he and 30-40 men from among the leaders of Mat rode up to the pass to stop his advance. They met on the pass and courteously embraced one another. Zogu then led Essad back to the village of Lis in Mat, to the manor of Kurt Aga Kadia. With Zogu were Shahin bey Dino and Stavro Stavri.

There they held talks and Essad sought Zogu’s support. Zogu replied as follows: “Uncle, you have started out on your journey and I raise my hand to you and wish you well. When I learn that you have achieved your objective, I shall say congratulations.”

Essad was infuriated at this reply and gave orders that a force be put together to continue his advance, but Zogu replied: “According to custom, since you are in our territory, you must drink coffee with us. For this, we need to go to Burgajet this evening.” Essad thus accompanied Zogu to Burgajet where the latter hosted him and all his men at his own expense.

Once again, Essad tried to persuade Zogu to join him, but Zogu refused categorically.

Xhelal Zogu, however, gathered 1,000 men of Mat and joined Essad, though none of the other leaders of Mat went with them. They went to see the Çelaj family at Patin and from there continued on to Pazari i Urës for lunch. There, Mersin and Shaqir Dema were lying in wait to kill them, but their uncle, Sheh Lula of Zerqan, discovered what was going on and dispersed them.

Essad then arrived at the village of Selita e Keqe in the Tirana Mountains and continued on towards Tirana the next day. Coming from Shkalla e Tujanit, he took the Priska Pass, Mount Dajti and Mount Shkalla. There was much shooting in all directions. Essad got on his horse and set off for Shkalla with 500 chosen men. Waiting at Gryka e Shkallës was Abdi Feza of Bastar near Tirana and about 500 to 600 men. Abdi Feza was terrified and, instead of opposing Essad, he welcomed him. As such, Essad Pasha took Tirana without so much as a fight.

The ehli kijam leaders fled and Essad spent the next three days in Tirana. He financed his men and all the volunteers with his own money, paying them their wages, and then left for Durrrës. His men were opposed by a rebel force under Man Picari stationed at the latter’s inn, but the rebel force was defeated. The second impediment was the town of Shijak where Sheh Hamdiu and the people of Shijak had made substantial preparations to defend the town. With his usual trickery, Essad sent an advance delegation and convinced Sheh Hamdiu to collaborate with him. He thus overcame resistance in Shijak without any problem. The last and greatest hurdle was Rrashbull where the men of Shijak and Kavaja fought heroically and the men of Dibra lost 86 of their fighters. At last, on 3 October 1914, he made his way into Durrës.

Aside from Hamdiu, Mustafa Ndroqi and Hoxha Leçini, the ehli kijam leaders all fled. In the Bumçi manor, Essad lost no time in setting up a senate from the men he wanted and, using his troops from Dibra as a threat, he forced this assembly to elect him as head of the new government of Central Albania and as commander-in-chief of the army.

Essad immediately declared war on Austria. His government consisted of the following figures: he himself was prime minister and commander-in-chief, Shahin Dino was made responsible for foreign affairs, Nehat Libohova for finance, Faik Kodra of Dibra for internal affairs, and Isuf bey Dibra became commander of the army. A political court was set up under Xhelal Zogu, with Ilia Llavda of Durrës as prosecutor and Hysen Mushqeta as chief investigator.

Turkey entered the war on the side of the Central Powers on 3 November 1914 and it was on this occasion that Essad declared war, sentencing the members of the Ottoman military court to death for treason. As such, all those who favoured Turkey, and the Young Turks turned against Essad, but he arrested many of them to break their resistance. Among those arrested were Musa Qazimi and Haxhi Qamil Feza. However, seeing that these arrests were not having the desired effect, he released them and sought their support and collaboration. Musa Qazimi was actually in favour of supporting Essad but did not dare to express his support.

The Young Turks, as said, turned against Essad and dissolved the commission of Haxhi Aliu that had gone to Istanbul to call for Burhanedin to be made monarch of Albania.

Essad had the support of some of the beys, of his Dibra troops and of his foreign allies, the Greeks, the Serbs, the Montenegrins, Italy and France.

On 23 November 1914 Haxhi Qamili burned down the Essad Pasha’s manor on his property in Lapraka, and his house in Tirana. He then attacked Tirana and drove out Essad’s mercenary forces under the commander of Xhelal Zogu and Dino Hoxha. Haxhi Qamili then burned down the manors of other bey and agas, such as Murat Toptani, Refik Toptani, Fuat Toptani, and Isuf Elezi, most of whom were supporters of Albanian independence.

Both the supporters of Turkey and the Young Turks joined Haxhi Qamili and on 6 November 1914 they decided to fight Essad, who was then surrounded in Durrës. All of the settlements that had been under his rule automatically came under the rule of the ehli kijam.

In April 1915, Durrës was attacked and shelled severely, but it was nonetheless vigorously defended.

To overcome the siege he was under and to gain access to central Albania and Dibra, Essad, assisted by Salonica and Serbia, sent Faik Kodra to Dibra to recruit more men to come to Kruja and liberate Tirana and the other parts of central Albania with fighters from Kruja.

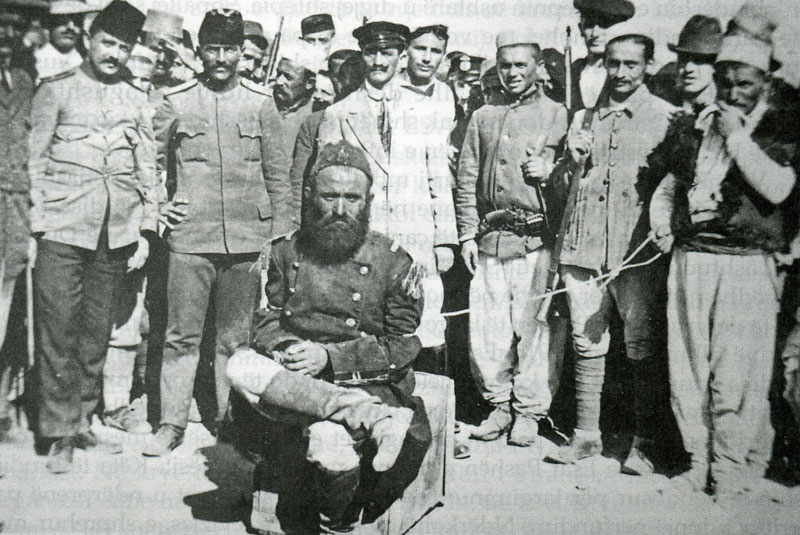

The captured Muslim rebel leader Haxhi Qamili (1876-1915) in June 1915 before he was hanged.Ceno bey Golja was the prefect of Dibra at that time and, assembling a force of some 2,000 men, he sent them off to Kruja. The leaders of Kruja were Sul Haka, Abaz Kupi and Hysen Kuqi. In a meeting, they decided to call Essad to come and take part in the fighting himself. On 24 December 1914, Essad arrived in Shëllinza and on 26 December he set up his military headquarters in Tapiza and deployed most of his men to the village of Zeza near Kruja. The other side, under the leadership of Haxhi Qamili and Man Picari, sent a force of some 2,000 men, both villagers and city dwellers of Tirana, who attacked Essad’s men at Zeza and defeated them on 29 and 30 December.

Essad assembled his remaining men at the tekke in Kruja. There, in a speech, he promised their leaders that he would get back to Durrës and would bring them food and weapons. He then dismissed them from duty.