| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

![]()

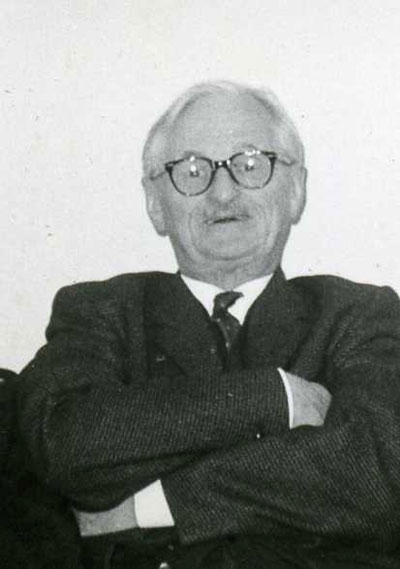

Vandeleur Robinson (1902-1990)

1941

Vandeleur Robinson:

Corruptio ad AbsurdumBritish writer and military figure Vandeleur Robinson (1902-1990) was the son of an army colonel. In the 1930s, after studies in history at Emmanuel College in Cambridge, Robinson was active for the League of Nations as a regional organizer for southeastern Europe. It was there that he met his second wife, the British war correspondent and journalist Clare Hollingworth (1911- ), to whom he was married from 1936 to 1951. The couple spent their honeymoon in the Balkans and were also in the southeastern Europe for several months before the Second World War, when they first visited Albania. It was this visit that gave rise to Robinson's book, "Albania's Road to Freedom" (London 1941). Some would claim that the chapter from this book, given below, which deals with corruption in the Albanian public administration of the Zogist period, has certain parallels to modern-day Albania.

Corruptio ad Absurdum

One of King Zog's difficulties was to find the right men, who would help him to modernise his country, without his relinquishing that strong grasp upon authority which was essential. He found a country but lately emerged from Turkish rule, with all the corruption and other faults which the Turkish system implied. In the dozen years between the overthrow of the Turks and the attainment of power by Zog, the country had experienced several foreign occupations, several local or ephemeral Governments, and, for the rest, lawlessness. Some of its men were accustomed to rule—but according to Turkish standards, now abandoned by Turkey herself; the others were used only to oppose authority, whencesoever it might spring.

Only three or four years ago, the Assembly of the League of Nations was discussing a Report of the Mandates Commission on the administration of Palestine. There arose a delegate who claimed special knowledge, by reason of having once been Governor of Palestine. This was no other than the delegate of Albania, Mehdi Frasheri, who, before the Great War, had governed Palestine for a time under the Turkish Sultan. The Hamidian despotism is as near to us as that. This kind of man was the material that Zog found ready to his hand when he was looking for administrators, Ministers, diplomatic representatives, officials, Prefects. As well appoint the present British Cabinet to be Commissars in a Soviet State, as expect these relics of the Ottoman Empire to introduce modern administrative standards in Albania, or to keep to them personally if they were established.

Government buildings in Tirana

(Photo: Richard Busch-Zantner,1939)

The first principle of the State Service in Turkish times was, "Muzzle not the ox that treadeth out the corn". Moreover, the overlapping careers of bureaucracy and politics were looked upon—and still are looked upon over wide stretches of the globe, including parts of the British Empire—as the authentic path by which a poverty-stricken peasant may rise to influence and affluence. It was the Albanian peasant who became a Moslem, and placed his talents at the service of the Sultan, who stood the best chance of ending up as a Pasha, a Viceroy, or a Grand Vizier. Both in lapse of time and in religion, Albania is the least removed of all the Balkan countries from the Ottoman Empire and its traditions.

The young man who wants to get on enters the public service. Even Tribal Chieftain Zog made his career by serving the Regency as Commander-in-Chief and Minister of the Interior, and thus came to power. The peasant gets a job in a Ministry or a Prefect's office, and goes forward from there. His salary will be extremely small; there will be a large deduction for "National Economy"—in other words, to enable the King to get along for a while without another Italian loan. Some years ago the salary often did not arrive at all; in any case, it would not be large.

That is the other main cause of the trouble. A country as poor as Albania—or as stingy as Hamidian Turkey—cannot offer generous salaries to its Civil Servants; they must reward themselves "on the side" as they go along. The beginning of fortune is to extract a douceur from a petitioner, for procuring him an interview with the official whom he has come to see. Before you get to the Prefect or the Magistrate or the Minister, who has power to settle your business, you give a present to the clerk who admits you. If you do not, the clerk states that the Minister is engaged; and the Minister never knows that you have called.

The higher positions give even greater opportunities. Imagine yourself a Minister, about to award a contract for laying a large number of concrete blocks in the sea at Durazzo, in the form of a pier. Italy has just advanced the money—on which you will, of course, draw liberally for "expenses". Your brother-in-law has got some concrete, or knows where to get some, and the bill will not be too closely scrutinised. Dishonest? Yes, but how is a man to live? A Cabinet Minister's salary is thirty pounds a month; what sort of a career is that going to provide? Next month the King will perhaps dismiss you, and there is no pension. Moreover, you are now the prosperous member of your family; your relations are all clamouring for sinecures, subsidies, pensions, jobs, contracts, or Heaven knows what. You need a new European suit to receive foreign journalists; a frock coat to attend the King's banquet; an endless supply of smokable cigarettes. Living is cheap? Yes, but not so cheap if you live as a European. Finally, you have to live somewhere. At home in the mountains you were brought up in a shack; that won't do for Tirana. What you need is to buy a plot of land in the Boulevard Zog and build a nice modern villa, with a garden and a wall round it. That costs money; lots of money. Your capital is represented by a few pounds that you managed to save (if you did) while you were Assistant Prefect in a provincial town. So how are these things to be paid for? Well, there is this contract for the totally unnecessary Durazzo breakwater, which the Italians are so keen about. What about a rake-off?

There are two preoccupations in the mind of the Minister. The first is his rake-off; the second, how to create the necessary alliances, window-dressing for the King, and so forth, to make likely a further spell of power after the first. This costs money too, so let's take a little more on the rake-off!

At risk of weariness, it must be repeated that this window-dressing, sweetening, and rake-off are not new sins specially developed by the Albanians; they are the legacy of centuries. In Turkish times, everybody who was not content to mind the cattle in his village, or grow things for a bare livelihood, always lived on the rake-off, be he Pasha, tax-gatherer, official's clerk or servant, or merely a local magistrate dealing with the landed Bey. Since, when Albania became independent, everybody remembered that, when he was young, everybody took a rake-off or a bribe as a matter of course, the social conscience which condemns these things practically did not exist—at least among the class which first found itself in the Albanian public service. Nor could Zog create conscience by removing temptation, except at the cost of filling his empty Treasury with an Italian loan—on Italy's terms. Often he did so fill his Treasury; but it did not last long. For the same reason, all his other excellent schemes, for land reform, agricultural banks, agricultural and other education, and Heaven knows what improvements, were perpetually held up, and were spread over decades, when a single year would have sufficed in a less penurious country.

The conditions of the service being what they were, everybody was willing to point the finger at somebody else for taking bribes—particularly if he himself, not being in the public service, had no opportunity to get rich that way, and only endured despoliation as a tax-payer and a briber. People used to speculate upon the honesty or otherwise of this or that official. The test was simple. Mr. So-and-so came to office a poor man; we all know his father and mother, and their miserable farm. He has been in office for a few years, and has now resigned. Is he a rich man, or is he still poor? Does he go quietly back to the family farm, like Etem Toto? Or has he built himself a nice house, and does he continue to cut a dash in Tirana? A British politician might get away with his increased wealth, on the ground that an admiring old lady had left him a fortune, or he had won a packet on a double, and increased his winnings on the Stock Exchange; or he might have been made (between bouts of office) a company director, with generous fees; or he might have written a book or two, or some sensational and well-paid newspaper articles. In a word, the poor man in politics may become moderately rich without serious (or even any) dishonesty. It is not so in Albania. If the once poor public servant has got him a nice house, the price of it can only have come, some way or another, out of the public purse, or out of bribes; the emoluments of office would not run to it, and there is no Stock Exchange, no well-paid journalism, to account honestly for the money.

While some Ministers were supposed to make a good thing out of the Ministry of Finance or the Ministry of Public Works, others, such as Mehdi Frasheri and Etem Toto, enjoyed a reputation for complete honesty. It should be said at once that, particularly of late years, there was an increasing number of genuinely honest men in the public service; the Gendarmerie, the schools, residence at Western universities, and the fundamental excellence of the native Albanian character, were producing a generation with an enlightened outlook. One meets Albanians in this country now, exiled with their Sovereign, upon whose principles and personal integrity, as well as their enlightened intellectual views, one would confidently rely. But not all Albanians looked with the same eyes upon an honest public servant; a few years ago one such man died, as poor as he began, and a bystander at his funeral remarked, with pity for such eccentricity: "There goes another fool!"

It would be grossly unfair to leave the impression that the whole collection of Albanian politicals was riddled with graft and peculation. If the picture has been overdrawn in this chapter, it serves to show what King Zog had to contend with. Helped by the various agencies mentioned above, and by the effluxion of time, he succeeded in effecting notable improvement. That his task was not completed is due to the Italians, who obstructed his work all along the line, and finally cut it short.

[extract from: Vandeleur Robinson. Albania’s Road to Freedom (London: Allen & Unwin, 1941). pp. 115-119.]

TOP