| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

Hermann Neubacher (1893-1960)

1956

Hermann Neubacher

A Nazi Diplomat on Mission in AlbaniaHermann Neubacher (1893-1960), an early member of the Nazi Party in Austria, was mayor of Vienna (March 1938-December 1940) and then joined the German foreign service as an expert in economic affairs for southeastern Europe. He was active in Romania, Bulgaria, Greece (October 1942) and finally, in Belgrade in August 1943 as special emissary of the German Foreign Office for Southeastern Europe. From 11 September 1943, after the fall of Italy, he was also made responsible for Albania, and worked closely with the Wehrmacht until Germany’s capitulation in 1945. In 1946 Neubacher was detained by the Americans and sent to Belgrade, where in 1951, he was sentenced to prison as a war criminal for having supported German forces as an economist and diplomat. He was released in November 1952 and returned to Austria. Neubacher is the author of the book ‘Sonderauftrag Südost, 1940-45’ (Special Mission Southeast, 1940-45), Göttingen 1956, in which he details his high-ranking activities for Nazi Germany in the Balkans. The book includes the following chapter on Albania.

The Founding of a State

There was little mention of Albania when I received my orders at the Führer’s headquarters at the end of August 1943 appointing me as “Special Envoy of the Foreign Office for Southeastern Europe.” Vittorio Emanuele was still king there, and a Luogotenente held the reins of power on his behalf. Germany had a consulate general run by Herr Schliep. But on 8 September, when General Eisenhower announced a ceasefire with Italy, Albania became of such importance, due to its geographical position on the narrow Straits of Otranto, with enemy forces now on the other side of it, that I was only able to take over the office in Belgrade from my predecessor Ambassador Benzler, in October. For this reason, I shall deal with Albania before dealing with Serbia and Montenegro, although this not in line with the chronology of my mission.

The job description of by duties in Albania was unusual because of the laconic wording. Ribbentrop called me in Belgrade and informed me that the Führer wanted an “Albania independent of its own initiative.” I was to travel the very next day, 11 September, to the German Division in Elbasan. A chartered aircraft would bring me a specialist on the Albanian language and the geographical and political situation there, and he would accompany me to Albania. I was to take Tirana with this division and fulfil my mission.

Three weeks earlier, at the General Headquarters, I had managed to acquire some superficial knowledge of the political situation in Albania and had met two Albanian politicians who wanted to talk to me right after the fall of Italy: Xhafer Deva, who played a political role in the formerly Serb region of Kosovo, and Vehbi Frashëri, the son of the subsequent chairman of the Regency Council, Mehdi Bey Frashëri, who at the time was still in internment, living with his daughter Mediha in a hotel in Rome.

It was late in the evening when I discovered that there was no airstrip in Elbasan. There was not enough time to change the whole expedition and use to cars, so I decided, without consulting the General Headquarters, to fly on the morning of 11 September directly to Tirana that was still under the control of Italian troops. A advanced parachute company flew in before me and landed in Durrës. The enemy was very close, right across the Adriatic. To show the presence of the German Armed Forces, three Ju52’s with sixty men of the Brandenburg Division (Abwehr II) landed at Tirana airport just before my Heinkel III aircraft did. Xhafer Deva ordered himself a Storch aircraft in Kosovska Mitrovica. His hour had dawned.

Xhafer Deva

(1904-1978)After a nice flight over the magnificent and wild mountains, Tirana with its minarets came into view in the green valley at the foot of Mount Dajti. I did not know anything about conditions at the Italian airport and ordered the aircraft to taxi up to the main building. Out of it rushed an agitated crowd of Italian officers and crews. These poor soldiers, without ships to take them back home and now at the mercy of their one-time allies, were understandably in desperate straits. I clambered out of the plane. It was difficult for the agitated crowds to recognise who I was in a black diplomatic uniform unfamiliar to them. But the large amount of gold on my cap, the golden buttons and the well-ironed creases of my uniform made it evident that I was a dignitary of some unknown military unit. I was shown to a little hut on the left side of the airfield. There was German ground personnel there. The plane taxied in that direction. The young fellows in shorts and in good humour seemed delighted at our arrival. Consul General Schliep picked me up in his limousine.

What a scene! There were thousands of armed Italian soldiers in the streets and public squares, clustered in nervous groups. It was a losing battle for them in the hostile environment. It would have been suicidal for them to offer resistance to their one-time allies. They expected the arrival of the Germans at any moment. To fight on? To give up their arms? Have themselves taken prisoner, with their homeland so near and yet to unreachable? One could only feel sorry for these troops, abandoned to their fate by the course of events. They willingly yielded to our vehicle. The soldiers saluted at the sight of my gold-covered cap. We advanced slowly through the crowds to the Consulate General.

* * *

I discussed the situation with Herr Schliep and Herr von Scheiger, the Albania-expert seconded to me by the General Headquarters. Scheiger, a one-time Austro-Hungarian General Staff officer, had lived in Albania for over twenty years following the First World War and was an encyclopaedia of knowledge on Albanian tribes, clans and family issues. The situation was very confused. Parts of southern Albania were in the hands of communist partisans whom the Italians had tried to suppress, but without success. This is the reason why a German division was deployed to Elbasan before Italy’s fall. These partisans would become tomorrow’s guerrilla resistance fighters. The nationalist fighters (Balli Kombëtar – the National Front), who had withdrawn into the mountains after the Italian occupation, constituted less of a danger because we were not their main enemy. As in Greece and Yugoslavia, their principal foe were the communists. The Albanians were well aware that we had only invaded out of pure military necessity, to protect our flank from an Allied attack from across the Straits of Otranto. I do not remember any hostile act against German forces committed by the population. In addition to this, Germany had a good reputation in Albania. This reputation had suffered somewhat as a result of German acquiescence to the Italian invasion of 7 April 1939, but the Germans were now disarming the Italians and we now had a tremendous opportunity to increase our own stocks of arms. The population still had good memories of the very tactful methods used during the Austro-Hungarian occupation in the First World War and this led to the German invasion being well-accepted everywhere. Seeing well-disciplined elite troops behaving in a friendly manner to the civilian population had an engaging effect on this proud mountain people who were themselves wont to bear arms.

The men of Balli Kombëtar never did battle with our troops. They either dispersed or directed their energies against the partisans in the south. Only Abaz Kupi, who regarded himself as the viceroy of King Ahmed Zogu, remained in the mountains around Tirana and Shkodra, apparently with thousands of supporters. With him were some British liaison officers. We left him alone and he left us alone. He had a good reputation in the country, and in October 1943, the constituent National Assembly conveyed official greetings to him in the mountains. That did not bother us. There were no demonstrations against us. It was simply recognition for a freedom fighter who had stood up against Italy, the country that had annexed and taken over the country.

This will suffice as a brief sketch of the political background to the events of the coming days, and I will now return to my mission: German Headquarters had requested an Albania independent of its own initiative.

This was in the air, but the air was ominously laden. Rumours, spread by zealous agents, came in by the hour about an imminent British invasion, from which I assumed that such an invasion would never occur. Since Roman times, the Albanians have had a traditional strategy to deal with occupations. It has been custom among this small but martial mountain nation, not wishing to be squashed by mightier plunderers, to seek gold and weapons from the strong and to seize them from the weak when they withdrew. They have maintained themselves in their mountains for centuries. But now, it was uncertain who would retain power. The Italians were defeated and had been disarmed, with the zealous assistance of the Albanians throughout the country. What wealth of arms found its way into the stone towers of Albanian farms! Would the Germans manage to hold on there, who on the other side of the Adriatic were being pushed back northwards by superior Allied forces? Should an independent Greater Albania be proclaimed under the auspices of the German Army? Should we wait for an Allied landing and fight them there?

Two men, each working initially on his own, endeavoured to set up a representative National Committee to declare Albanian independence and to take over the reins of an interim government in the country: the veteran Albanian Ibrahim Bey Biçaku of Elbasan and the Kosovar Xhafer Deva of Kosovska Mitrovica. There were negotiations day and night. In order to preserve the inviolability of their “own initiative,” I refused to get involved in these frantic talks, and waited. I did one thing, however. On the evening of 12 September I flew back to Belgrade so as to avoid any appearance to pressuring the parties. On 13 September, I returned to Tirana and waited for the National Committee to be created, without receiving any news of its progress. I always stressed to our friends that it was in the vital interests of the country that the German Army and German diplomats have a stable national government to deal with. Otherwise, interference in the local administration and economy would be unavoidable. If responsible men did not come forward and take the destiny of their country into their own hands, we would of necessity have an occupation regime, something we wished to avoid.

On 14 September the two groups agreed on a Committee to be headed by Ibrahim Bey. It was to be composed of twenty known and well-respected figures. Political parties were of no importance here. I received the delegation at the Consulate General. Professor. Tsallaris, who spoke fluent German, informed me in passionate and perfect speech that a National Committee had been founded and had proclaimed the independence of Albania. The Committee expected the Government of the German Reich to recognise the independence of this united Greater Albania. With a clear conscience, I was able to inform them that I would transmit the request of the National Committee without delay to the German Government and that this was in accord with the purpose of my mission. The improvised ceremony was particularly solemn. The exhilaration and enthusiasm of this historic moment was interrupted by the hospitality of Frau Schliep who brought in drinks, that were eagerly received by the thirsty fathers of the nation.

The same day, I paid an official visit to the National Committee that was meeting in Prime Minister’s building, and returned the next day to Belgrade. After a short stay there, I flew back to General Headquarters to hand in my report. Hitler, who had a lively interest in this last romantic corner of Europe, seemed very satisfied with the course of events.

I was soon back in Albania. The National Committee took over the provisional government, under Ibrahim Bey Biçaku. Xhafer Deva took over internal affairs. Everything that had been run by the Italians stopped functioning: the administration, the court system, the police, the gendarmes, the military, i.e. all the basic attributes of a State ceased to exist. All that remained was the tradition network of family, clan and tribal relations with its own solid structures and laws. German soldiers provided an ideal of order, even though they were only guests.

And they were only guests. When the Supreme Command of the Germany Armed Forces delegated a Military Commander for Albania, I protested to the German Foreign Minister that this was an error, and drew his attention to the sovereignty of the new Albania, that we had desired and recognised, and to the fact that there was no German competency there in matters of administration and legal affairs. The error was immediately recognized and the Military Commander for Albania became a “German General for Albania” who had the mission of representing the interests of the German Armed Forces with the Albanian Government. The relationship between the General and the Government, and between the troops and the population remained excellent to the very end.

The first concern of the provisional government was to convene the National Assembly in order to form a government based on the old Zogist Constitution. This Assembly met in October in the Royal Palace. I informed the provisional government of Germany’s recognition of Albanian independence by conveying a letter to the Chairman of the National Committee, Ibrahim Bey Biçaku. Fräulein Lützen, aware of the historic significance of this document, found a sheet of parchment for it, but even this was not ceremonious enough for us. It needed a seal and cord. I did not have a seal, but I found a solution. We certified in a footnote that a copy of the document would be stored in the archives of the German Consulate General and this certification was attested by the huge, thick-edged seal of the Consulate General. Now it looked ceremonious enough to satisfy the prerequisites of the Orient, always more devoted to such details than the West. I was received by an improvised guard of honour consisting of about ten men of martial posture, no difficulty for these Dinarics. I climbed the staircase and entered the hall in which the National Committee was meeting. One does not simply walk in such cases, one strides ceremoniously. Speeches and replies were held. As there was no further protocol involved, we toasted Albania’s sovereignty with some wine. It was a very nice event.

* * *

In the first initial days of my appointment in Albania, I inquired as to who were the most prominent figures of the country. I soon came to realise that one man enjoyed universal respect: Mehdi Bey Frashëri. Neither offers nor threats from the Italians could bring this old imperial Ottoman official to accept Italy’s annexation of his country. The importance of his person had caused Italy to exile him to Rome where he lived with his daughter Mediha in a pleasant hotel, limited though his freedom of movement was. After Italy’s surrender, I provided him with a Heinkel III aircraft and he flew back to Tirana. This aircraft also brought back the old Albanian banknotes stored in the Banca d’Italia, for the Albanian National Bank. This Albanian National Bank had been set up by Italian experts and was very well organised.

Mehdi Bey Frashëri, 74-years-old at the time, was an impressive individual. He stemmed from a leading family of feudal beys, had begun his career in the Turkish Balkans as an official in public administration, and served later as a pasha in the Lebanon and in Egypt. He stood like a monument left over from the Ottoman Empire. His wife was Turkish, a lady of some dignity and grace. Mehdi Bey spoke at least eight languages, but no German. We usually conversed in Italian.

He observed recent developments with some reserve. When he realised that it was not a question of a German occupation regime, he became much more actively involved in his country’s destiny. Ardent appeals in the National Assembly to his patriotic duty moved him to take up the position of first chairman of the Regency Council, that also included an Orthodox and a Catholic representative. The Council was headed by them alternatively. He was, however, the only permanent representative because his Orthodox colleague fell ill and the Catholic representative, the Franciscan prior of Shkodra, Father Anton Harapi, rejected the position as incompatible with his functions as a Catholic priest because it might compel him to confirm death sentences. This was music to the ears of the old pasha.

The Constituent National Assembly, and the Regency Council elected by it, selected a definitive government. Rexhep Mitrovica, a Kosovar, was appointed Prime Minister, Xhafer Deva, Minister of the Interior, and Vehbi Frashëri, State Secretary for Foreign Affairs. The Zogist Constitution was retained. The king was replaced by the Regency Council. The National Assembly dissolved all ties with Italy and proclaimed an alliance with the Axis Powers. Everything went smoothly. But not without a some commotion. A group of partisans, known for their impetuousness, that had taken part in disarming Italian units, brought an Italian canon within firing distance and shelled the Royal Palace where the National Assembly was meeting. The artillery men were soon put to flight by German soldiers who brought things back into order. No one was injured. The whole incident seemed to correspond to the genus loci. The Albanians are one of the peoples of earth who are most devoted to shooting off fire arms. The rifle is not an instrument for the Albanian, it is part of his body. A guest who has visited someone’s home is honoured on his departure by the firing of guns at a certain distance. The modern submachine gun offered new, unlimited possibilities to this ceremony. In a country so devoted to weapons, an artillery response to a government ceremony seems to be exactly what was called for, and no problem from a protocol point of view.

* * *

Mehdi Bey Frashëri, if I may be the judge, was the inventor of a new category in international law. He suggested that Germany should recognise the neutrality of Albania. It was to be a ‘relative neutrality.’ Albania regarded the German Armed Forces, brought to Albania simply out of military necessity, as its guests, despite its neutrality between the warring powers. The Albanian Government would act to counter all espionage jeopardizing the internal peace of the country. Should Germany’s enemies attack with troops having the character of military units, Albania would remain neutral.

I then defined Albanian sovereignty as a ‘relative sovereignty.’ The German Armed Forces, as friends of the Albanian people, wished hospitable treatment in a country they had only entered out of military necessity. Germany recognized the sovereignty of the Albanian Government with only one limitation – we would have to oppose any government that gave support to our enemies. For this reason, the sovereignty of Albania was ‘relative’ for the sake of the security of our troops.

We agreed to this wording and the General Headquarters took official note of Albania’s ‘relative neutrality.’

I had no problems with the General Headquarters in Albanian affairs because there was no one there who had the slightest idea of this amazing corner of Europe. For this reason, no one could contradict me. In addition to this, there was much good will in Germany for this little known country. I may add in this connection that the legendary fame of the Albanian national hero Skanderbeg (15th century) and the most widely read German author for young people (between 10 and 80), Karl May (author of “In the Land of the Skiptars”), did much to explain this German good will.

Few people, however, knew that this little mountainous country had given rise to Roman legions, Roman emperors, Byzantine mercenaries and generals, grand viziers and Egyptian khedives, and that the pope had bestowed the title of “Defender of Christianity” upon Skanderbeg.

* * *

The German Armed Forces, with their maximum strength of two divisions, needed money to pay for expenses in Albania to build roads and fortifications and to procure local products, etc. Initial needs were covered by loans from the Minister of Finance, but in such a small country, these funds were very limited. There was a shortage of paper currency. Printing money was fortunately not possible because important printing blocks had been lost in Italy. As such, we paid for our subsequent expenses with gold and foodstuffs. From the gold reserves I had been allotted for Greece, I put gold onto the free market in Albania and gave the banknotes to the Armed Forces. This constant influx of gold of course served to prop up the local currency and it remained afloat right to the end. The most popular gold coin in Albania is the Napoleon (20 gold francs). The gold pound was worth less by comparison. In Greece it was the other way around. This had nothing to do with the amount of gold in the coins. The value of the gold coins was determined simply by their popularity. The most sought-after commodity after the Napoleon was the submachine gun. Whoever had enough of both and distributed them liberally, was a welcome guest.

Our rear positions were protected by Albanian gangs under the leadership of their tribes and clans. They protects us primarily from groups of partisans who became more and more prominent with the decline of Germany’s fortunes. There were of course occasional problems with our volunteers and helpers. One time, a mountain fighter and his retinue were provided with trucks, weapons and Napoleons, and then simply disappeared with them in an impressive cloud of dust. The general of the Waffen SS and the police, Fitzthum, who was acting as technical advisor for the establishment of an Albanian police force, reported the case to me in a rage, and was shocked when, having read his report, I broke into laughter. I could vividly imagine the dapper fighter, armed to the teeth, saying farewell with fiery glance and heroic gestures to our Fitzthum, who himself had an inclination for the romantic and had read his Karl May. What a magnificent figure he must have been! The gentleman thief!

These mountain people have a word of honour, that they keep. They call it besa (trust). This besa is one of the basic characteristics of the patriarchal society of the Albanians, in addition to vendetta and hospitality. Anyone breaks his besa, loses his reputation, and is no longer trusted by the community. The besa is not offered lightly and is not easy to get, but if one gets it, it holds. Wherever it’s a question of life and death, one is obliged to have the besa of the men one is relying on. This word of honour is the institution for which the Albanians are best known. The advance of western civilization will certainly do it no good.

* * *

When I took over my Albania mission, there were applicants in Kosovo for the Muslim Waffen SS Division, Handjar, that was set up in Bosnia. With Kaltenbrunner’s support, I managed to get Himmler to stop recruitment for the division because it did not accord with our policy of neutrality. But the Reichsführer SS, who had heard much of the famous elite regiments of Bosnia and Hercegovina in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, finally achieve his aim. He got authorization from Hitler in 1944 to set up a Waffen SS Mountain Division called Skanderbeg for the local partisan war within the country’s borders. It suffered very heavy casualties in a badly led advance into partisan territory at an early stage of training. I was not at all happy with the setting up of this division, but the Albanian Government did not mind because it hoped that it would serve as the core for a well-trained national army and police force. The division had its headquarters in Prizren. I prevented its deployment in the area of Kosovska Mitrovica that remained with Serbia because I was afraid it would commit excesses against the Serb population. Serbs and Albanians have no great love for one another.

After the fall of Yugoslavia in July 1941, the Kosovo and Metohia region, inhabited primarily by Albanians, joined the Italian Kingdom of Albania set up in 1939. The Albanians lost no time in driving as many Serbs out of the country as they could. Those who were expelled were often forced by local potentates to pay a fee in gold to be permitted to leave the country. They were simply following the example set by the German Reich with its emigration tax. When General Nedić complained to me bitterly about this, I recommended urgently that the Albanian Government put an end to the expulsion of the Serbs. Realising that my intervention had been unsuccessful, I threatened to resign from my Albania mission, stating that I would have to leave it to someone else to protect Albania from the expansionist intentions of Bulgaria. Xhafer Deva, who was influential in Kosovo, promised to intervene, and did so with success. Nonetheless, much harm had been done since 1941.

The Bulgarians were constantly complaining about Bulgarians being murdered in eastern Albania where there are virtually no Bulgarians. They did this in order to persuade Germany to hand over the occupation of these territories under threat. I sent Colonel von Kohoutek, a member of my staff in Belgrade, down to the area north of Lake Ohrid to conduct a political analysis of the murders that had occurred there over the last couple of months. Colonel von Kohoutek carried out a thorough analysis of over forty murders. There was not one Bulgarian among the dead. Almost all the murders stemmed from vendettas, family and clan feuds, or were homicides as a result of brawls. One murder was a contract killing of one communist by another. Some cases of homicide could no longer be elucidated. Following this detailed analysis of the crimes, an occupation of Albanian land by Bulgarian troops did not seen necessary, a result which detracted substantially from my reputation in Greater Bulgarian circles. I was already in their bad books when I played a role in preventing the holding of the referendum in Thrace.

* * *

Prime Minister Rexhep Mitrovica, was suffering from lung disease and resigned in June 1944. Ill as he was, he was never able to do much. The political scene was dominated by the conflict between Old Albania (Mehdi Bey Frashëri) and New Albania (Xhafer Deva). Xhafer Deva also resigned in June 1944 to seek medical treatment in Germany and then devoted himself entirely to promoting his powerbase in Kosovo.

I thus experienced three weeks of an Albanian government crisis that I will never forget. From this time on, we did not recommend any candidate. Day after day, there were new combinations, information, counter-information, influence, counter-influence. The mighty breakers of politics rolled in and crashed at the edge of the charming bungalow where I had set up my headquarters in Tirana. Prominent guests arrived in town, with their bodyguards from the mountains and stayed at the beautiful Hotel Dajti, built by the Italians, so that they would be in close proximity when the new Minister of Finance took over his office. The well-greased rifles and submachine guns belonging to the protectors of these dignitaries gave the hotel a rather martial atmosphere.

Finally, I pretended that I had given up all hope of a quick solution and left the country by plane, without saying good-bye to anyone. I do not know if this gesture had any real influence on the situation, but shortly after my departure, the last favourite won the day: Fiqri Dino, a fellow from Dibra. He had good contacts with Abaz Kupi, whose headquarters were under British control. At the beginning of his candidacy, Fiqri Dino told me that he would only take over the reins of government if Germany promised to equip two mountain divisions (with tanks). I am still convinced today that this demand stemmed from Abaz Kupi, who had come up with the idea with the help of his British liaison officers, in order to acquire an arsenal of weapons before Germany’s withdrawal, which would not be long off, and to use them to repulse the partisan advance. This attempt by the last British intelligence service chief in Albania only served to strengthen my conviction that they should negotiate with us during our withdrawal from the Balkans – Germany had already lost the war in any event – so that German troops could remain in Albania, hold on to their bases and not let any weapons seep in the hands of the population, until they were evacuated “honourably” as prisoners of war. Such suggestions were also made by our secret service for our division (General Lanz) in northern Greece. It must not be forgotten that western access to Albania was blocked by Moscow and the British should have paid attention to the possibility of a communist coup d’état, which inevitably took place.

In view of all this, I had the impression that things had far surpassed the humour stage.

* * *

Meetings

I have already written about Mehdi Bey Frashëri. He left the country with his family and a number of dignitaries when the German soldiers withdrew. His son Vehbi settled in Vienna and pretended to be Viennese. A second son was English-oriented and even looked like an Englishman. The head of the family was a genuine Albanian patriot, neither germanophile, nor anglophile, nor bitterly opposed to the Italians while they were in power in his country. He had been marked by his past as a high official of a great empire whose fall he had experienced. He had the routine and dignity of a man who had always borne much responsibility. With his compatriots, he was our guest in Vienna and in Kitzbühel. Like all the other Albanians, he left Tyrol, with my best wishes, just before the US invasion, and headed for Italy and Switzerland.

Mehdi Bey’s rival in the government was the Minister of the Interior, Xhafer Deva, who was enemy number one of the communists. He survived an assassination attempt that killed his adjutant. In actual fact, due to the new borders, Xhafer Deva, from Kosovska Mitrovica, was a Serb citizen, as the Serb Prime Minister, General Nedić once pointed out to me with some bitterness. After the restoration of independent Albania, Xhafer Deva moved with about 1,000 compatriots from Kosovo via Peć [Peja], Prishtina and Prizren to Tirana. The slogan of his men was “Terror for Terror.” He wanted to show the communists his teeth, and did so in the local fashion. In Shkodra, a number of communists had taken refuge in the Papal Mission that was destroyed on that occasion. Xhafer Deva intended to remain in the country after the withdrawal of German troops and conduct a guerrilla war. At the last moment, when the Germans neglected to give him requisite technical equipment for this fight, he fled to Croatia and reached Vienna in December 1944. We last saw one another in Kitzbühel (Tyrol). I do not know how many men who had been prominent in Albania while we were there, fell into the hands of the communists. I do know of three who were arrested: the Franciscan prior, Father Anton Harapi, the last Prime Minister, Ibrahim Bey Biçaku, who succeeded Fiqri Dino, and Professor Tsallaris, who was Deputy Speaker of Parliament. Tsallaris spoke fluent German and had studied German philosophy and literature. I do not know why he stayed in the country. I believe it is possible that he regarded it as his moral duty.

Ibrahim Bey Biçaku, the scion of a great family from Elbasan had also studied for many years in Vienna and was well acquainted with German culture. He was a very kind man, modest and rather introverted. As head of the National Committee that took over the reins of provisional government on 14 September and as the last Prime Minister while German troops were withdrawing, he marked the beginning and the end of a dramatic phase in Albanian history. An Albanian refugee from Durrës told me in a Belgrade prison cell that he had fallen victim to his passion for gramophone records. He sorted and sorted the records he wanted to take with him on his escape until it was too late.

The same refugee told me about the death of Father Anton Harapi. But I must digress here for a moment. When we began our withdrawal from Albania, I earnestly besought Father Antonius to leave the country and offered him my aircraft. He sent me his thanks and informed me that God had called him to be where he was and, if it were God’s will, he would die where his duties were as a priest.

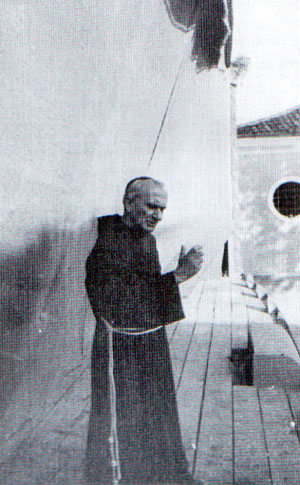

Anton Harapi

(1888-1946)The fellow from Durrës told me that friends of his had hidden him. The communists, who were looking everywhere for him, broke into the house where he was staying, but could not find him. On departing, they noticed some dentures in a glass of water and went back to talk to the owner of the house. When they began to mistreat the fleeing owners, Father Harapi crawled out his hiding place and surrendered. My informant told me that he went to the gallows with peace of mind.

Father Anton Harapi was from northern Albania. He had gone to secondary school at monastic schools in Meran [Merano] and Hall in Tyrol, and had studied theology in Rome. Before his death, he revisited the placed he had lived as a young man. His departure from Tirana at the time was unusual.

It was at the end of June 1944 when I had had enough of the government crisis and left Tirana. My plane could only depart at night because of the proximity of British fighter aircraft on the other side of the Straits of Otranto. The aircraft was taxing down the runway when it was brought to a stop by ground staff, shouting loudly. “What has happened? Who is it?” “It is Father Harapi!” At that moment, the little Franciscan crawled into the aircraft and stood there, with a smile, in the passenger cabin.

“I have lost my patience with politics. I am going with you!”

The Heinkel aircraft set off again, soaring out of the valley and over the isolated mountains, on the slopes of which the rising sun had cast its first magenta rays. Father Antonius, sitting across from me in his habit, took his breviary out of his one bag and began to pray. He was my guest in Belgrade for a couple of days. I can still see the small ascetic figure in front of me, with his brown, weather-beaten face and a large, funny nose, as he paced back and forth in my garden with the breviary in his hand. Father Anton then travelled on to Vienna and back to Tyrol. A few weeks later, he returned to Albania where death waited for him.

No revolution can extinguish the memory of such a man. He will always be illuminated by the eternal light he served.

[extract from: Hermann Neubacher, Sonderauftrag Südost 1940-45: Bericht eines fliegenden Diplomaten (Göttingen 1956), p. 105-121. Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.]

TOP